| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $0.00 |

| Total | $18.00 |

Store

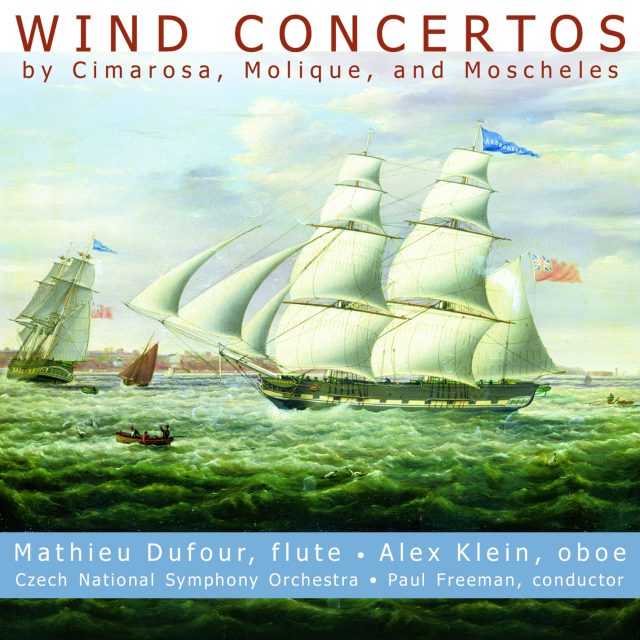

Flutist Mathieu Dufour and oboist Alex Klein — current and former principal players of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra — shine as soloists in a CD of neglected gems from the early Romantic era. Charming virtuosic showpieces by Mendelssohn contemporaries Wilhelm Bernhard Molique and Ignaz Moscheles astound with their fresh melodies — and with the jaw-dropping technique and expressive range they elicit from the wind soloists. Opening the program is a jewel of the high Classical period: Domenico Cimarosa’s beloved Concerto for Two Flutes (played on flute and oboe).

Preview Excerpts

DOMENICO CIMAROSA

Concerto for Two Flutes in G Major

WILHELM BERNHARD MOLIQUE (1802-1869)

Concerto in D Minor for Flute and Orchestra

IGNAZ MOSCHELES (1794-1870)

Artists

7: Wilhem Bernhard Molique

Program Notes

Download Album BookletWind Concertos

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Concertos emerged during the Baroque period of European musical history, 1600–1750, and evolved into two basic types. Antonio Vivaldi was the prime practitioner of the solo concerto: one instrument, most typically a violin, in a clear soloistic role contrasted with a small orchestra. Vivaldi established the solo concerto as a three-movement piece arranged fast tempo/slow tempo/fast again. Within these movements were sharply-articulated sections for the orchestra alone, and for the soloist with the orchestra accompanying. The other Baroque pattern is that of the concerto grosso: a group of soloists contrasted with the orchestra. The alternation of sections is similar to that in the Vivaldi type solo concerto, but the contrast is less marked, the soloists’ group is more integrated into the overall texture, and the sensation is more of conversation than of rivalry.

Bach and Handel, the Baroque giants, produced concertos in both styles. Handel’s numerous concerti grossi are augmented by solo concertos featuring his own favored instrument, the organ. Meanwhile, influenced by Vivaldi but going beyond him, Bach produced works that both culminated a style and pointed the way to the future. His six Brandenburg Concertos are concerti grossi that explore all kinds of different relationships among individual soloists, soloist groups, and orchestra. At the same time, Bach also defined and developed the solo concerto with works for harpsichord, violin, and oboe.

Composers of the Classical era — the heyday of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven — continued to refine and expand the solo concerto genre. With Mozart and Beethoven, the genre’s development focused especially on works for piano and orchestra. Both of these compositional geniuses were outstanding keyboard artists; in most cases, they were the soloists for whom they wrote these works. Their interest, however, went beyond the solo part: they fused the concerto style with the sonata-form framework characteristic of symphonies. The result is a body of work that offers formal as well as soloistic interest; instrumental dramas that offer contrast, confrontation, and eventual reconciliation between soloist and orchestra, all in the context of fully worked-out symphonic structures.

Meanwhile, the concerto grosso had not been entirely forgotten: it was transformed into something called the sinfonia concertante. In this genre, the idea of multiple soloists is retained from Baroque times, but the works are usually longer and more symphonic in scope. Like Classical solo concertos, sinfonia concertantes employ first-movement sonata form (modified to accommodate the alternation between solo and orchestral passages in the regular concerto tradition). What sets a sinfonia concertante apart from a Mozart or Beethoven solo concerto is the impression of dialogue among the soloists as well as between the soloists’ group and the orchestra. The emphasis is not on drama but on cooperation; the soloists tend to emerge from the orchestral texture rather than stand out in relief against it.

Our CD starts with a brilliant example of a sinfonia concertante, although Domenico Cimarosa didn’t use that name when he penned his Concerto in G for Two Flutes, played here by flute and oboe. Six years older than Mozart, Cimarosa was raised in Naples, where he showed talent as a singer, organist, and violinist. He wrote the first of his many comic operas in 1772, and before long his stage works were being performed not only in Naples but also in Rome and Milan. In 1787, he became music director at the court of Russia’s Catherine the Great, an appointment that lasted just four years, partly because Catherine was running out of money to pay imported musicians, and partly because Cimarosa couldn’t stand the Russian winters. He settled briefly in Vienna, once again becoming an imperial music director. His first work for Austria’s Leopold II was The Secret Marriage, the only Cimarosa opera that has remained in the repertory. The Secret Marriage was both the high point and the turning point of Cimarosa’s career. When Cimarosa returned to Naples in 1793, he became embroiled in revolutionary politics — on the anti-Royalist side — and endured a short imprisonment. His health declined under the stress and he died in 1801, at age 51.

The majority of Cimarosa’s output was vocal: operas, masses, and cantatas. His instrumental pieces include keyboard sonatas, a handful of symphonies and quartets, a concerto for harpsichord, and the Two-Flute Concerto, which dates from the same time as The Secret Marriage. If this concerto were an opera, its first movement would represent the hero and heroine meeting and interacting with a community, encountering conflicts and resolving them; the second movement would be a love scene, and the finale an exuberant wedding dance.

Though often featured in duets by themselves, the soloists are also treated as integral parts of the orchestra. Instead of waiting through an orchestral opening, they join the full orchestra (oboes, bassoons, horns, and strings) right from the start. Their lines in the Allegro first movement generally run together in harmonious intervals of major thirds, though sometimes they engage in short dialogues. In keeping with standard Classical practice, there’s a short cadenza just before the end of the movement.

Cimarosa’s gorgeously lyrical Largo, much shorter than the Allegro, is in the nature of an interlude showcasing the soloists, allowing them to stand out as individuals more strongly than before. The main key of this movement is striking: the mellow E-flat major, quite distant from and offering a clear contrast to the Allegro’s bright G major. The Largo doesn’t really end; it leads, with just a short pause, straight into the rollicking Rondo finale. Some listeners have heard echoes of folk music in this Allegretto, which certainly dances right along. Starting softly, the main tune suddenly becomes more emphatic as it moves from the violins to the soloists. The short contrasting episodes that set off the rondo theme don’t interrupt the momentum, which feels carried over from the Largo. Since both Largo and Rondo are cast in triple meters, 3/4 and 6/8 respectively, they seem linked in opposition to the straightforward 4/4 pace of the opening Allegro.

As the 18th century became the 19th, the Romantic preoccupation with individualism and expressive passion subsumed the ideals of balance and clarity characteristic of Classicism. The era and its attitude toward artists as individuals, not as members of a kind of servant class, helped give rise to the cult of the virtuoso: performers on just about any instrument, or singers, who often cared as much about presenting themselves as about the music. Two prime virtuosos were the violinist Niccolo Paganini and the pianist Franz Liszt, whose tours attracted the kind of cult following we’d associate nowadays with the Rolling Stones or the Grateful Dead. Virtuoso players needed virtuoso concertos, works that placed great emphasis on technical fireworks. The 19th century produced a great many of these.

The newest edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians contains a comprehensive survey of the origin and evolution of the concerto. Several authors contributed to this detailed history including American conductor Leon Botstein, who wrote about concerto composition and performance during the 19th century. Botstein cites a contemporaneous German commentator of that time named August Reissmann who criticized most concertos as mere display pieces, vehicles for show-off soloists unworthy of consideration as “serious” works. Reissmann was not alone in this charge, writes the conductor, and it has not entirely disappeared from critical writing today. Botstein continues:

The question is whether this widespread and conventional assessment of the bulk of the works produced throughout the century, based on the distinction between superficial and entertaining virtuosity, and higher musical values — a veritable cliché of concerto criticism from Schumann to the present — should be accepted at face value, in the precise terms suggested by the critics themselves. Twentieth-century taste, as mirrored in conservatory training and concert programmes, absorbed and accepted the dismissive verdict of the 19th-century observers; the result has been the banishment of the vast majority of 19th-century concertos from the concert stage. That group of works actually contains many concertos deserving of re-examination and performance. The barrier to the revival of many fine concertos, some of them by performer-composers with few other compositions of note to their name, has been the legacy of a 20th-century puritanical rejection of the popular aesthetic tastes of 19thcentury audiences as well as the undeniable difficulty and time commitment required on the part of soloists (who can expect little in the way of reward or praise for extending their repertoire) to learn such works.

This 20th century attitude is exemplified by a quote from Igor Stravinsky: “In order to succeed,” he once said, “[soloists] are obliged to seek immediate triumphs, and to lend themselves to the wishes of the public, the great majority of whom demand sensational effects.” (Not many musical figures could manage (or afford) to put down both virtuosos and audiences in one sentence.)

Such attitudes notwithstanding, Botstein’s point is highly valid: There’s a lot of enjoyable music from the virtuoso era to be rediscovered — as evidenced by the three gems from that forgotten repertory which come to life on this CD. These were created by two performer composers who were famous and respected in their day, but are now relegated to relative obscurity. Since most performer-composers wrote exclusively for their own instruments, it’s notable and telling that Molique and Moscheles were able to look beyond their own performing skills to write for other virtuosos.

Wilhelm Bernhard Molique was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1802. He died in 1869 near Stuttgart, where he’d served a number of years earlier as music director for the local ruler’s court. His principal instrument was the violin; his musical hero and mentor was the German violin virtuoso and composer, Ludwig Spohr. The widespread reputation of the Stuttgart orchestra during the 1830s and 1840s has been attributed to Molique’s genius as a teacher. He undertook concert tours as a violinist and was especially well-liked in London, where he settled during the 1850s in the tripartite role of chamber musician, teacher, and composer.

Molique composed his Flute Concerto during these London years: it was published there, though with no date attached. The orchestra — flute, oboe, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and strings — presents a majestic opening that soon gives way to a lively flute solo with the ensemble very much in the background. The orchestral return shifts from D minor to D major and picks up some of the flute’s melodies. There’s an abbreviated development section, exploring several new keys, but the dominant interest is in the soloist’s elaborate figurations. The recapitulation, involving both soloist and orchestra, provides a traditional ending in D major, punctuated by a short flourish of a cadenza.

The song-like middle movement, in G major, is strongly reminiscent of Mendelssohn in its sheer lyrical beauty. The structure is a straightforward application of the “A-B-A1” format: an opening section, a contrasting middle, and a varied return of the opening. We’re back in D major for the Rondo finale, which again recalls Mendelssohn in its cheery tunefulness. There’s no soloist’s cadenza here, but none is needed: the entire movement shows off the flute’s virtuosity in continuous flights of fancy.

Molique wrote his single-movement Oboe Concertino in 1829 for the Stuttgart soloist Friedrich Ruthardt. The piece was not published during the composer’s lifetime, however. The work divides into three distinct sections that parallel the usual three-movement concerto structure, but on a reduced scale. The orchestral scoring is for flute, clarinet, bassoon, horn, tympani, and strings. Here the symphonic introduction is shorter, more urgent, and more dramatic than in the Flute Concerto, and the soloist begins participating immediately with his own elaboration of the opening theme. This section is comparable to an operatic recitative: a free-ranging passage for a singer recounting past events or anticipating those to come. The music moves on to a calmer midsection via a smooth transition to the major mode (B-flat and F). Here is the aria to follow the recitative, and it’s harmonic flavor provides further evidence of Mendelssohn’s influence on Molique. By far the longest portion of the Concertino is the third, for which the orchestra takes us back to G minor. The oboe presents a straightforward tune that’s immediately elaborated with runs and trills covering its whole range. A more lyrical theme briefly emerges. There are constant transitions between major and minor before the work ends in G major. On the way, we are treated to what amounts to an accompanied cadenza, as the oboe displays every facet of its sound and of the performer’s talent.

While Molique’s style in these two works may remind us of Mendelssohn, there’s no evidence he ever met his eminent contemporary. Ignaz Moscheles, on the other hand, was one of Mendelssohn’s teachers who later became a close friend and colleague. Born in Prague in 1794, Moscheles won success as a composer and conductor, and especially as a pianist; he frequently toured Europe, earning raves wherever he performed. Like Molique, he was noted as a teacher. In 1846, when his touring years were coming to an end, he became a professor of piano at Mendelssohn’s newly-founded Leipzig Conservatory, where his students included Edvard Grieg. Moscheles also knew Chopin and Liszt, but found their piano-playing too exaggerated. As with Mendelssohn, Moscheles leaned toward a Classical ideal even in the midst of Romanticism, at least when it came to performance styles. His compositions, though, show the Romantic characteristics of chromatically-enriched harmonies, strong dramatic contrasts, and high levels of expressiveness.

Molique was the conductor and Ruthardt the oboist for the premiere of Moscheles’s Concertante in Stuttgart in 1830. Since Moscheles never had any connection with that city, this may at first seem puzzling. It’s reasonable, however, to speculate that Ruthardt’s virtuosity was known widely enough that Moscheles composed the piece specifically for him. The flutist on the occasion was another leading Stuttgart soloist, Gottfried Krueger.

Flute and oboe are joined by an orchestra featuring pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, with tympani and strings: similar to Molique’s orchestra, but with more multiple parts. Opening the Concertante is an extended, emotionally intense section labeled “Adagio Patetico.” Again the style of an operatic recitative comes to mind as the soloists engage in a long, dramatic duet over chromatic orchestral harmonies. Low strings followed by higher ones lead into a dramatic pause, a short cadenza, and the launch of the Rondo section. The main theme is introduced by the soloists, who continue to dominate the texture with dialogues and duets, continually presenting new themes and variants. Asserting itself at last, the orchestra takes up the rondo theme, but this “tutti” is merely the signal for the soloists to return with a lively concluding duet.

Album Details

Total Time: 70:51

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond and Pete Goldlust

Cover: “The Barque Andromeda in Two Positions” (1831, oil on canvas) by Samuel Walters (1811-82). Ferens Art Gallery, Hull City Museums & Art Galleries, UK, Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded: June 12-14, 2003 at the studios of ICN-Polyart, Prague, Czech Republic

© 2004 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 080