| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

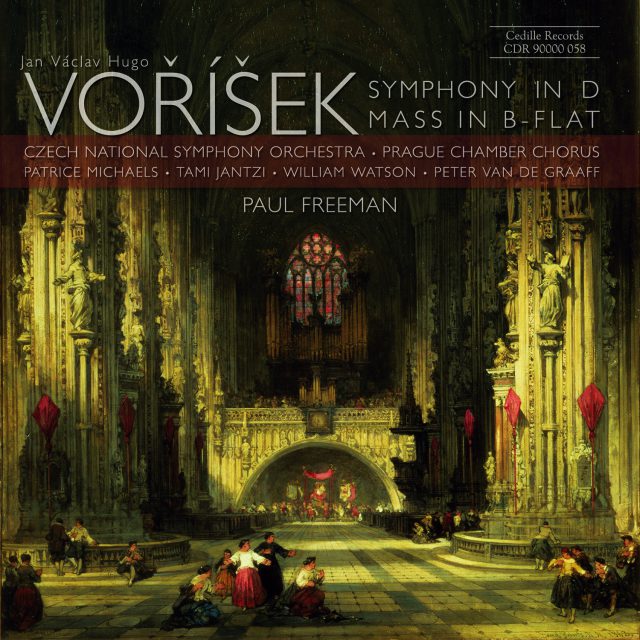

Voříšek: Symphony in D, Mass in B-Flat

Paul Freeman, Czech National Symphony Orchestra

Patrice Michaels, Peter Van De Graaff, Tami Jantzi, William Watson

Combine Schubert’s gift of melody with Beethoven’s flair for drama, and you have the music of their respected friend and colleague — the Bohemian composer Jan Václav Hugo Voříšek. Unlike his better-known contemporaries, Voříšek (pronounced VORH-zheh-shek) composed few large-scale works in his tragically short lifetime (1791-1825), but what gems they are. His exquisite Mass in B-flat Major is a perfectly proportioned Classical masterpiece in the tradition of the great masses of Haydn and Mozart. Surprisingly, this new CD is the only readily available recording. Voříšek’s only symphony, the Symphony in D Major, is “a work of impressive confidence and command, firmly constructed and colourfully scored” (Gramophone). If you love the great Viennese classicists, you’ll adore Voříšek.

Preview Excerpts

VOŘÍŠEK JAN VACLAV HUGO (1791-1825)

Symphony in D Major

Mass in B-Flat Major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletVoříšek: Symphony in D and Mass in B Flat

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The Austrian Empire of the 18th and 19th centuries encompassed vast territory and incorporated many different peoples and cultures. The nations we know today as Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia were all included, plus (at various times) parts of Italy, Romania, Poland, and the Balkan states. Controlling all these lands and nationalities was never easy, as historians have detailed in their accounts of the Hapsburg monarchy. The rulers in Vienna could not completely eliminate uprisings, dynastic rivalries, and breakaways, but they kept a tight grip on many aspects of ordinary life by suppressing native languages, imposing all political and legal authority from afar, and generally treating the majority of the population as second-class citizens.

Nationalism, both political and cultural, asserted itself strongly in the late 19th century and spread worldwide in the 20th, which witnessed the breakup of colonial empires in Asia and Africa, the dramatic formation and dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the struggle to define national identity that continues in such far-flung locales as Indonesia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. In the 18th century, however, the domination of one state by another was taken for granted.

As we look back on 18th-century Europe, we see a picture of at least superficial peace and order. It really was, to a considerable extent, an “Age of Reason,” relatively responsive to progressive ideas — as long as those ideas did not threaten the wealth and privilege of the ruling classes. The history of Vienna exemplifies the era’s remarkable contrasts. On the positive side were the reforms of two “enlightened” rulers, the Empress Maria Theresa and her son, Joseph II. Their era was followed by the 1815 Congress of Vienna that ended the destructive Napoleonic Wars. It had the further and less hopeful effect, however, of reinforcing reactionary governments, keeping the status quo firmly in place.

Most ordinary people of the time were unaware of, or at least indifferent to, the historical forces that influenced their lives. People got along as best they could in the station of life to which they were born. Usually, one stayed in his native village or town and followed his parents’ trade. There were some ways out (for young men at least), especially for talented musicians. Many performers from the provinces even made it all the way to Vienna, the Classical era’s musical mecca.

Many residents of Austrian-dominated Bohemia took this route — so many that the country was dubbed “the conservatory of Europe.” Mozart VORˇ I ´ Sˇ E K : SYMPHONY IN D AND MASS IN B-FLAT notes by Andrea Lamoreaux was acquainted with numerous transplanted Bohemians, or Czechs, and called them “the most musical people in Europe.” Back home, they had few opportunities: German was the language of the schools and the elite; German culture was respected, Czech traditions despised. Taking an “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” attitude, Czech musicians turned their eyes and ambitions toward Vienna and the German capitals.

In an essay about the symphonic music of Jan Václav Hugo Voříšek and his celebrated successor, Antonín Dvorˇák, Uwe Kraemer writes: “In this period of political, social, and cultural devastation, many Bohemian musicians, seeing no opportunity to pursue their profession in their own country, emigrated westwards and enriched musical culture in unexpected ways. Jirˇí Benda created the art form of the melodrama, in which a dramatic text is not sung but spoken to an orchestral background. Jan Václav Antonín Stamitz was one of the most important composers of the pre-Classical Mannheim School. Antonín Reicha achieved distinction as one of Beethoven’s teachers, and in the court orchestras of the Baroque and Classical eras many [chairs] were occupied by the finest Bohemian virtuosos.”

Professor Kraemer goes on to say that Czech musicians failed to establish their own voice during the 18th and early 19th centuries, burying their individuality in the prevailing style. The great Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušnýhad a somewhat different take on the subject, however. For a recording he made in the 1960s of works by Benda,Voříšek, and other turn-of-the-19th-century Czechs, he wrote: “There is in the musical style of these composers a definitely Czech character, that is, a certain melodic style close to the Czech folksongs, and use of thirds and sixths also derived from Czech folk music, as developed later by Smetana and Dvorˇák. In spite of the international environment in which [they] lived, and the influence of the international currents of the period, many of the Czech elements prevailed in their music.”

The works on this CD show the truth of Firkusˇn´y’s insights while also revealing significant influence of Voříšek’s Viennese contemporaries. As one might expect, the Mass is the more “classical” of the two pieces; church music is inherently conservative. The symphony reveals some of the influences Voříšek absorbed in Vienna and blended with his own distinctive voice.

Born in 1791 in the small village of Vamberk in northeastern Bohemia, Voříšek started out with a strong advantage that would ease his move from small-town to big-city life: his father had some education and functioned as the local schoolmaster, organist, and choirmaster. Thus he was able to teach his son, encourage his youthful pianistic talent, and help him win a scholarship to the University of Prague in 1810.Voříšek studied law at the University but never lost his fascination with music. His desire for a significant career in music quickly grew to the point that even the capital of Bohemia could not accommodate his ambitions. Prague in the second decade of the 19th century was still enthralled by Mozart, and while hardly objecting to Mozart,Voříšek was far more inspired by the dramatically innovative works of Beethoven. It was in the hope of meeting Beethoven that Voříšek made his most significant life transition, moving to Vienna in 1813. He was 22; tuberculosis would cut his life tragically short 12 years later.

The adjustment was not as difficult as it might have been had he chosen, say, London; his way was smoothed by the émigré artists who had preceded him. Today’s TV journalists and newspaper feature-writers might call it “the Czech connection”: compatriots already established in Vienna introduced him to leading musicians including Spohr, Moscheles, Hummel, and his special idol, Beethoven. Voříšek’s university training enabled him to get a job in the Emperor’s civil service, and a friend helped him obtain the position of conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Friends of Music Society) in 1818. He also gave both private and public concerts as a pianist, and became Imperial Court Organist in 1823, beating out eight other prominent applicants for the post. It was in conjunction with his imperial duties that Voříšek composed his Mass. When he died, the court music director wrote: “Art thus loses a noteworthy, pre-eminent composer, and the court chapel perhaps the first among living organists.”

Beethoven expressed approval of some of Voříšek’s piano pieces, but the most far-reaching contact the young man made in Vienna was with Franz Schubert. His principal teacher at home, Jan Václav Tomášek, “pioneered the Romantic piano piece in ternary form, with poetic titles such as Impromptu, Rhapsody or Eclogue,” according to Voříšek biographer Adrienne Simpson; “with Voříšek the style made its transition to a true 19th-century idiom, especially in the treatment of the left hand and in certain aspects of harmony. In turn, Voříšek may be said to have passed the style on to Schubert, since he knew him well, and his own Impromptus Op. 7 were published well before Schubert’s.”

The great Viennese classicists — Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert — all wrote Mass settings. Voříšek’s is on a somewhat more modest scale than Haydn’s Mass in Time of War or Mozart’s Great Mass in C Minor, but its musical qualities — its melodic ingenuity, its projection of the text — are on the same high level as those of his more famous classical-period predecessors. In its rich harmonies, permeated by those thirds and sixths that Firkušný notes, it is reminiscent of Schubert’s sacred works, but there is no question of imitation or derivation. It is an original, new-sounding work, conceived within the conservative traditions of liturgical music that were, no doubt, strictly enforced at the religious services of the Viennese court.

Gone from sacred music in this era were the elaborate contrapuntal configurations of Bach. The voices in Voříšek’s Mass move more homophonically, and there are fewer fugues. Voříšek knew and loved the tradition of contrapuntal writing, which he learned from his teacher Tomášek, but employed it more in his keyboard compositions than in his Mass. Contrasting choral singing with passages for a group of soloists had been a standard feature of Mass composition for several generations before the 1820s. Voříšek’s use of this technique is especially striking in the second part of the Credo (I believe in one God). After the Kyrie (Lord have mercy), Gloria (Glory to God), and first part of the Credo largely dominated by the choir, the solo voices enter with the words “Et incarnatus est” (And [Jesus] was made man) cast in the minor mode. Only with the exultant words “Et resurrexit” (And he rose from the dead), does the mode shift back to the major, sung by the full choir. For the final part of the Credo, “Et vitam venturi” (I believe in the life of the world to come), Voříšek employs one of the work’s few fugues. Precisely because fugal passages appear so infrequently, this section is especially striking, serving to highlight the importance of these words in the Christian statement of faith.

One of the most exultant sections of a Mass is the Sanctus (Holy, Holy), which can conjure up images from the Biblical Book of Revelation, with angelic choirs eternally singing “Hosanna.” Voříšek’s brief yet majestic Sanctus provides a strong contrast to the more serene passage that follows: the Benedictus (Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord). Here the solo voices take over, with quieter but no less devotional “Hosannas.”

The Mass ends contemplatively. The minor mode returns as two violas play a yearning duet that sets the stage for the supplication that follows, with solo voices initially, then the choir, offering the prayerful Agnus Dei (Lamb of God, have mercy on us). Gentle tympani strokes contrast with the lyrical string lines; the violas return briefly, echoing the voices’ entreaties. The finale, Dona nobis pacem (Grant us peace), is a homophonic chorus similar in melody and sonority to the opening Kyrie. Voříšek concludes his Mass quietly, offering the musical equivalent of a sincere, straightforward prayer.

It is surprising that this exquisite Mass is not better known and more frequently performed. Indeed, that none of Voříšek’s music has yet entered the standard repertory ranks as one of classical music’s most glaring oversights. Some pianists know his keyboard music, and one occasionally stumbles across a recording of his magnificent Violin Sonata in G major, Op. 5, but the only work that can claim a somewhat respectable following is the Symphony in D that he wrote in 1821.

The outer movements of Voříšek’s symphony are reminiscent of Beethoven’s First and Second symphonies, although Voříšek’s melodic invention is closer to that of Schubert’s early symphonic works. (Voříšek probably got to hear some of Beethoven’s symphonies, but not Schubert’s, which received very few performances until the late 19th century.) Beethoven was never a great melodist; he frequently constructed themes out of simple scale patterns, using development to build up their importance. Schubert placed more emphasis on sheer melody. Voříšek, in his single symphony, achieved an extraordinary synthesis of the two composers’ approaches to orchestral composition.

The first movement is perhaps the most indicative of how much Voříšek revered Beethoven, and of what they both owed to the vigor of Haydn, who transformed the symphony into a major musical genre. A cohesive formal structure of exposition, development, and recapitulation is infused with short, dynamic motives that lend themselves to expansion. In the finale, the composer lets loose his fondness for chromatic melodies and sudden contrasts: loud vs. soft, quick shifts between major and minor modes. These devices keep us ever attentive to the music’s unfolding, as prominent wind and brass passages provide instrumental color against the mercurial strings.

Even more indicative of Voříšek’s individual voice are the symphony’s slow movement and Scherzo. The second movement showcases the orchestra’s low strings, which play a chromatic theme moving in half-steps: very unlike the standard symphonic themes of Mozart, Beethoven, or even Schubert. The theme and its developments are richly harmonized, using a great many of those thirds and sixths that Firkušný identified as characteristically Czech intervals. They’re characteristic of Schubert’s harmonies, too, but Voříšek achieves a subtly different sound in this lyrical interlude. The energetic Scherzo, resembling Beethoven yet not Beethoven, combines vigor and melancholy in a passage punctuated by striking horn calls. The Trio portion has a pastoral flavor, but the horn figures are still there to remind us of the drama that runs throughout this unusually inventive and charming piece.

Album Details

Total Time: 60:35

Recorded: November 8&9*, 13&14, 2000 in Prague, Czech Republic at the Dvorak Hall of the Rudolfinum (*Mass in B-Flat) and at the studios of ICN-Polyart (Symphony in D)

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Interior, St. Stephens Vienna by David Roberts (1796-1864). Courtesy of Guildhall Art Gallery, Corporation of London, UK / Bridgeman Art Library

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Andrea Lamoreaux

© 2001 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 058