| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

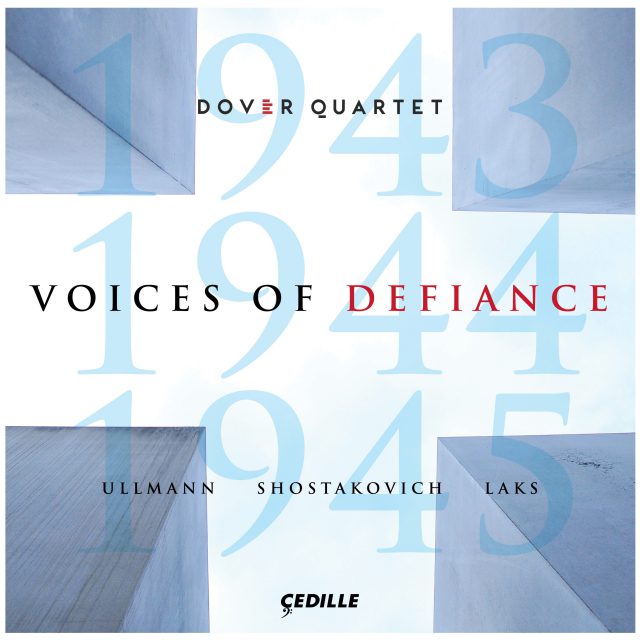

Voices of Defiance, the Dover Quartet’s second Cedille Records album, presents quartets of passion, hope, and resilience whose beauty defies the horrors that surrounded their creation.

“The young American string quartet of the moment” (The New Yorker) delivers an original, deeply felt program of three European composers’ distinctive responses to the destruction and despair of World War II. Czech composer Viktor Ullmann’s powerful String Quartet No. 3, written in the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1943, draws inspiration from Debussy’s Impressionism and Schoenberg’s serialism. The ensemble’s muscular approach to Dmitri Shostakovich’s epic String Quartet No. 2 from 1944 emphasizes its tragic qualities, befitting the album’s theme. A captivating discovery for most listeners, Szymon Laks’s lyrical String Quartet No 3, written in 1945 following his evacuation from Auschwitz and liberation from Dachau, revels in folk melodies from his native Poland in contrasting scenes of heartbreak and ecstasy.

Winner of a 2017 Avery Fisher Career Grant and the first prize and all special prizes awarded at the 2013 Banff International String Quartet Competition, this “terrific quartet” (National Post) brings its “confident, sinewy playing of distinctive sound and ample nuance” to this recording of profound 20th century masterworks.

Listen to Steve Robinson’s interview

with Dover Quartet’s Camden Shaw on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

VIKTOR ULLMANN (1898—1944)

String Quartet No. 3, Op. 46

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906—1975)

String Quartet No. 2 in A major, Op. 68

SZYMON LAKS (1901—1983)

String Quartet No. 3

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletVoices of Defiance

Notes by by Camden Shaw

Recording this album was an emotional process. Even disregarding historical context, the music itself is so powerful that it can bring tears to one’s eyes. But in the case of these particular works, knowing the darkness from which they emerged gives each note extra weight: they become at once even more tragic and more beautiful, the fragility and evanescence of the composers’ lives standing in sharp contrast with the immortal nature of their music.

The idea for the album arose slowly and naturally. We had been touring with Viktor Ullmann’s Third String Quartet for a while, and time and again we were pleasantly surprised by how many members of our audience already knew it quite well. In every city, it seemed, there were a few passionate music lovers who knew Ullmann’s story and were as obsessed with his work as we were; in several cases these same people would insist we look into the music of Szymon Laks. We’d never heard of Laks, and he remains a lesser-known composer, especially outside of Europe, but he was mentioned with such frequency that our interest was piqued. I’ll never forget the first time I heard the slow movement of his Quartet No. 3. It was like Barber’s Adagio for Strings in its emotional depth, but somehow also captured the plaintive cry of an old folk song. We were hooked. With the Ullmann written in 1943 and the Laks in 1945, we began looking for a quartet from 1944 in hopes of recording an album, and settled on the masterful second quartet by Dmitri Shostakovich.

All three men were affected by fascism and war — but the connection between Szymon Laks and Viktor Ullmann is particularly chilling. In his memoir, Music of Another World, Laks describes how he survived Auschwitz by becoming director of the orchestra there. In this quote, he recalls the arrival of new music stands for the Auschwitz orchestra:

After the regulation “Attention! At Ease!” the commander pointed to twelve black music stands in the corner and told us to take them, explaining: “I heard that you need music stands. Take these. I organized them especially for your orchestra.” We recognized those stands. They came from the Czech camp, which we once had the opportunity of visiting on official business. Last night the four thousand Czechs, whom we had envied for their carefree prosperity, had been turned into ashes. That was the price of these music stands.”

Laks was clearly at Auschwitz the day Viktor Ullmann was transferred there from Theresienstadt (“the Czech Camp”) and gassed to death. The two men never met, but for a few moments stood within earshot of each other in one of the darkest corners of human history.

This is a heavy album, but Voices of Defiance is not just about voices raised in protest. This music is defiant also in that its beauty defies the immense destruction that surrounded it. You can definitely hear the pain in the composers’ souls, and in the case of the Shostakovich, the message is one of immense tragedy. However, in this miraculous music you can also hear passion, hope, gratitude, and the tremendous resilience of the human spirit.

Viktor Ullmann: String Quartet No. 3

By no means did we sit weeping on the banks of the waters of Babylon. Our endeavor with respect to arts was commensurate with our will to live.

—Viktor Ullmann

Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944) was without doubt one of the most well-rounded and compelling musicians of his generation. Born in the present-day Czech Republic, he studied law, sociology, philosophy and music at the University of Vienna, where he attended the lectures of Arnold Schoenberg before moving to Prague to work and study with Alexander von Zemlinsky. Such an artistic pedigree was then the stuff of dreams, and judging from the exceptional quality of his work, Ullmann was poised to become one of the 20th century’s greats, had the war not intervened. Of his 41 opus numbers before his internment at the Theresienstadt concentration camp, almost none survive. Only 13 of his works can be found today, and two of the most famous were composed while in the camp: his chamber opera, The Emperor of Atlantis, and his third string quartet. When Ullmann learned that he was to be transferred away from Theresienstadt, he entrusted his manuscripts to a friend for safekeeping; it is not known whether he knew he was being sent to Auschwitz, but the decision to leave behind his works must have been a painful one, as he may well have suspected his fate. On October 16, 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz. Two days later he was killed in the gas chambers.

The influence of Schoenberg can be heard clearly in Ullmann’s third quartet, which features several passages inspired by the ideas of the Second Viennese School. As with every great artist, however, Ullmann’s vision was unique as he combined elements inspired by the Impressionist composers alongside those of twelve-tone writing, all without any break in continuity or radical shifts in compositional technique. The opening of this incredible quartet, for instance, employs the harmonic language of Debussy, but a few bars later, when the cello introduces the second subject, the melody uses eleven of the twelve chromatic tones, all without being strictly serialist in its composition. (The opening of the second movement also introduces eleven of the twelve chromatic tones.) The one truly serialist twelve-tone passage is a slow fugue at the end of the first movement, in which the 13-note fugue subject contains all twelve chromatic notes without repetition until the 13th note (at which point it was impossible not to repeat one). Ullmann makes this serialist moment his own, however, by freely composing tonal music to accompany the twelve-tone fugue subject. It seems his unique approach to the Second Viennese School was to embrace the sentiment behind twelve-tone composition without being a slave to its constraints.

The structure of this quartet is compact, yet extremely powerful and effective. While it has only two movements, the first contains a broad structure with several sections. Beginning with a slow, dreamy atmosphere, the mood quickly darkens with the brooding second subject and almost comes to a complete stop as all the instruments drop out except the cello. A violent, grotesque explosion follows, ushering in a passage in a fast 3/4 meter. Like the third movement of the Shostakovich quartet on this album, this section is a kind of demonic dance: brutish, manic, and sinister; it couldn’t present a steeper contrast with the exquisite colors of the opening. As a result, when the opening material — somewhat abruptly — returns, we experience it differently; it’s as if we can no longer trust it after such a horrific outburst. But instead of another frightening passage, the movement dances itself out quietly with the slow, mysterious fugue mentioned earlier: an enigmatic and hauntingly beautiful combination of twelve-tone writing and otherworldly harmonies. Only the last bar of the movement offers a surge of uncertainty, as though it might again erupt.

And it does. The second — and final — movement begins with all four voices in unison, with a stern but ambiguous character. Without any supporting harmonies to offer clues, we are not yet sure whether to interpret this passage as upbeat or mocking, knowing only that it is strong. The ambiguity continues as the mood suddenly shifts to a mischievous grazioso section, and then, out of nowhere, another explosion! We feel a gravitational pull to the end. There’s a brief, ghostly stretto based on the opening line and then, in one of the most satisfying moments in any piece for a performer, the material from the very first moments of the piece comes back in a thundering fortissimo, now unambiguously triumphant. Lush beauty combines with unimaginable power and determination to pull us to the end in a blaze of G-major chords. We know we have glimpsed into Ullmann’s great and powerful soul.

Who knows how many masterpieces we would have from this brilliant mind were it not for the unthinkable horrors of his time? Nonetheless, one thing is for certain: the world is lucky to be able to experience this masterpiece, in which we can still hear his spirit roar.

Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 2

That this is only the second string quartet of the 15 in Shostakovich’s output gives the misleading impression that it is an early work. However, by the time Shostakovich (1906–1975) wrote his second quartet he had already completed eight symphonies and was halfway through his life. The piece is also one of his longest string quartets, second only to his last; describing it as “epic” would not be an exaggeration. He wrote it in a mere 19 days at the Soviet-run artist retreat outside Ivanovo in 1944, during which time he also produced his famous Piano Trio No. 2.

In the description of the piece that follows, I must confess that some of the imagery I’ve included draws on our own subjective, personal response to the music. As this imagery directly impacted our interpretation, I’ve done so with a clear conscience. That being said, this music is bigger than any one interpretation and I would encourage listeners to develop their own stories to make sense of it.

The first movement, marked Overture, is said to be in A major, which is not untrue (the neighbor harmonies would seem to confirm this analysis). It is worth noting, though, that all of the A “major” chords at the opening and end of the first movement are missing the third of the chord, meaning that they are only open intervals and not technically in major or minor. This is the kind of detail that, to an interpreter, is invaluable. Either Shostakovich is referencing much older music (as Szymon Laks does in the finale of his third quartet) or he is indicating a state of emotional ambivalence. The tone is forceful and strong, but is it good or is it evil? It’s quite difficult to say, but if one imagines the opening with a bunch of complete A-major triads, instead, it would sound jarringly cheerful. Perhaps Shostakovich was trying to capture the spirit of the already battle-hardened protagonists of the Allies as they closed in on the Nazis — not happy, but determined to be a force for good.

The Recitative and Romance begins with a dominant seventh chord, aching to resolve, and also indicating that there should not be too much time between the first and second movements: the interruptive nature of this harmony must arrive with the end of the first movement still fresh in the ear. The movement is in A-B-A’ form, in which the A and A’ sections are recitative (the first violin ruminating freely above very slow harmonic changes) and the middle section is the Romance. One can immediately grasp the gravity of the first Recitative section: thoughts of death and darkness slowly melt away into more tender images over the course of several statements by the first violin, and that new tenderness dissolves into the Romance, which seems to be a memory or even a desperate hallucination in the mind of a soldier far from home. This interpretation is also supported by the frightening way in which the Romance becomes increasingly agitated and distorted: it ends in a cacophonous explosion of confusion and agony, at which point we return to the Recitative of the first violin, now sounding even more tormented and alone.

The Waltz movement employs one of Shostakovich’s favorite techniques: with each instrument using a mute, it takes on an otherworldly, ghostly, suppressed sound. He also juxtaposes the unmistakable rhythms of the Waltz, the dance most closely associated with elegant high society, with a sinister character that at times erupts into shocking violence; despite the mutes, some of the work’s loudest, most intense playing is in this movement. Shostakovich also gives the movement an incredibly fast metronome mark — about twice as fast as normal for a waltz — heightening the chilling impression that this “Waltz” may not be for the living. This whole movement, much like the Romance, seems to have the qualities of a dream or vision, perhaps on the eve of battle. And then the soldier wakes up.

The final movement, a theme and variations, is one of the most consummate examples of musical pacing that we have ever seen. Not unlike Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7, “Leningrad,” which chronicled the siege of Leningrad by Nazi forces, this movement builds in intensity, reaching its climax with such masterful timing that it is a compositional marvel. This is also the movement most related to the historical context of the year 1944, at which point Soviet forces were advancing on the Third Reich and were first beginning to witness the horrors of the Holocaust and the unimaginable devastation in Europe. It begins with a grave pronouncement in unison by the three lower voices, answered by the first violin — material that will resurface after the theme and all the variations, announcing the beginning of the end.

Between these bookend statements, there is an incredible buildup of tension, beginning with a simple song, played alone at first by the viola. To me, this sounds like the long march to battle, where one soldier starts to sing a familiar tune: first only one voice rings out, but slowly, others begin to join in. We hear each instrument play the theme in the first four iterations — viola, second violin, first violin, cello — at which point the theme starts to change. As the army nears its destination, we hear small skirmishes and the first surges of adrenaline as we sense real danger — but nothing can prepare us for the final two variations. The penultimate variation is very quiet, with a constant undulation in the cello beneath distant whistles of melody in the upper instruments (perhaps the soldiers smoke one last cigarette before dawn breaks and they rush into battle?) and then the final variation comes. You can feel the heart racing and the blur of it all — the mind too gripped by survival instinct to take much in — until the crushing blow of the opening pronouncement returns. Whatever one’s interpretation of the piece, the dread pervading the opening of this movement is fully confirmed in this moment. The theme is then broken beyond repair, played in a very slow, excruciatingly loud fragment ending in one last rising line in the viola followed by three soul-crushing A-minor chords.

Szymon Laks: String Quartet No. 3

Among the composers on this album, Szymon Laks (1901–1983) is by far the least known. He was born in Warsaw, but like many musicians in Europe at the time, he spent a great deal of time in Paris and Vienna. He made a living in Vienna accompanying silent films on piano; an eerie detail when one considers that he survived Auschwitz by providing music to “accompany” some of the most horrifying acts in history. While learning his third quartet for this album, all four of us read his memoir, Music of Another World, which recounts his experiences at Auschwitz. We strongly encourage anyone with an interest in his life, or simply in World War II, to read it: it is incredibly detailed and portrays the culture of Auschwitz in ways that could never be imagined. Laks survived the death camp because he was a musician and the camp guards were thirsty for entertainment: they provided the few musician prisoners with whatever instruments they could find, and the prisoners were expected to play as their fellows marched off to work — and to die — each day.

Music saved Laks’s life. Yet at the same time, the perverse ways it was used in Auschwitz left him horrified and disillusioned, realizing that music, his lifelong passion, could actually do harm. Here, he describes a visit to the women’s hospital, where he was attempting to lift the spirits of the sick:

After a few bars quiet weeping began to be heard from all sides, which became louder and louder as we played and finally burst out in general uncontrolled sobbing that completely drowned out the celestial chords of the carol. I didn’t know what to do; the musicians looked at me in embarrassment. To play on? Louder? Fortunately, the audience itself came to my rescue. From all sides spasmodic cries, ever more numerous [… :] “Enough of this! Stop! Begone! Clear out! Let us die in peace!” […] I did not know that a carol could give such pain.

One of the most heartbreaking passages in his memoir describes an instance in which a musician actually finds pleasure in his music-making, only to have the horrific events taking place around him prove just how insignificant that pleasure was in the context of Auschwitz:

He played as though inspired, so absorbed in phrasing the showy melody that he did not perceive the long line of trucks, packed with women, creeping toward the crematoria. With a smile, Doctor Menasche, proud of his performance, placed the instrument on his knees. The trucks disappeared around the bend. In one of them was the doctor’s daughter.

Laks survived the death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau for two and a half years, until it was evacuated by the Nazis. Just after the war ended, now with an irreversibly complicated perception of music in his heart, he composed this quartet. He based it on traditional Polish folk songs, which were strictly forbidden in the camps, and their inclusion here sends a clear message: he is trying to find his way home.

The quartet begins with a train whistle. Trains took Laks to Auschwitz, and also took him home. One can immediately tell that this is an ecstatic train ride — the urgent rhythms, the swirling of the wind through the windows: he is going home. The second subject, however, is extremely dark and melancholy. In the accompanying voices, he turns what was the beautifully swirling wind into smoke, and one feels hope drain away: on this joyful journey, there are painful memories that come back without warning. Still, the overall feeling is one of exaltation, and the movement glows with relief and joy.

The second movement, frankly, is one of the most impassioned and heartbreaking movements for string quartet I’ve ever heard. It seems to be based on two simple songs, perhaps old tunes that once brought comfort, and yet I have never before heard such a lonesome sound. The movement is not all sad: there are wonderfully optimistic moments and richly beautiful harmonies, but these sections are almost transitional when compared to the emotional gravity of the two lonesome themes. The second melody reaches a screaming climax in the middle of the movement that will send shivers down your spine. This movement alone provided reason enough to record this piece.

The third movement is one of the longest stretches of unison pizzicato that we know! After the soul-baring second movement, we need something to bring us back to life, and this is a breath of fresh air. There is a sweet and carefree dance in the Trio section that feels totally at ease and optimistic, as if we’re already back home.

The last movement, like that of the Shostakovich, is a masterful example of pacing. It begins very simply, with the ancient-sounding drone of open fifths that will permeate the movement and eventually build to a ground-shaking climax. Many things come to mind in this opening: we hear tired footsteps, but a resilient spirit; we hear a quiet, unwavering strength. To me, this movement sounds like Laks walking into his hometown for the first time after the war. There is the weight of many experiences on his back, and the wisdom that leads him not to expect much upon returning. Yet the closer he gets, and the more that familiar sights and sounds enter his consciousness, the more his joy grows, until it becomes a veritable hurricane. This movement is the sound of new beginnings, and of freedom.

Album Details

TT: (73:06)

Producer Theresa Leonard

Engineer Mark Willsher

Recorded March 19–21 2016, Rolston Recital Hall, the Banff Centre, Banff Alberta, CA

Graphic Design Rubric

© 2017 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 173