| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

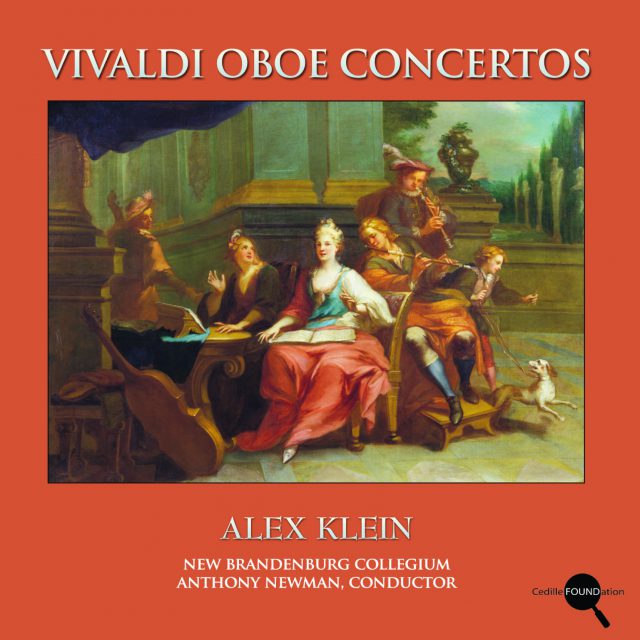

This mid-priced CD reissue of an album originally released in 1995 through the Musical Heritage Society presents Alex Klein, among the world’s top oboists, performing eight surprisingly diverse concertos by one of everyone’s favorite Baroque composers. His colleagues on the recording are the New Brandenburg Collegium, led by American conductor, composer, and keyboard artist Anthony Newman.

Preview Excerpts

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in A Minor, F. VII, No. 13

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in D Major, F. VII, No. 10

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in C Major, F. VII, No. 6

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in A Minor, F. VII, No. 5

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in F Major, F. VII, No. 12

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in D Minor, F. VII, No. 1

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in C Major, F. VII, No. 11

Concerto for Oboe and Strings in F Major, F. VII, No. 2

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletVivaldi Oboe Concertos

Notes by Alex Klein

A prolific and diverse composer, teacher, performer, and respected member of the musical community in Venice — then one of Europe’s musical capitals — Vivaldi is celebrated for his concertos and sonatas, and a few other works. His total output is astonishing: over 40 operas, numerous choral works, 90 sonatas, and, of course, 500 concertos. But we have very little personal information about him. In the case of Mozart, Beethoven, and even Vivaldi’s contemporary J.S. Bach, we are blessed with a wide variety of information we can use to understand the person behind the compositions. In turn, we can apply that knowledge to search for personality in his music, revealing how the composer spoke through his writing. We have become quite good at doing this with Mozart and Beethoven, and certainly with composers after them. But Vivaldi’s persona remains elusive.

Vivaldi taught music at the Ospedale della Pietá, a residence for orphaned or abandoned girls serviced by the Venetian Republic. We have few details of who these girls were and few of their names are known today. But we do have, in Vivaldi’s concertos — written for these girls with their growing abilities in mind — a good idea of their extraordinary capabilities. In this recording, you will hear examples of their artistry and command of the instrument, and of Vivaldi’s superior care and psychology as a teacher.

Vivaldi remains to this day a composer for whom we find connection mostly through his music, not from first hand and personal accounts. Vivaldi was practical, writing for the instruments he had at hand, but also an ambitious innovator. His composition techniques shocked his more conservative colleagues. In his most famous work, The Four Seasons, a collection of four violin concertos inspired by the changing seasons (a novel idea in itself), Vivaldi ornamented his music with instrumental approximations to singing birds, barking dogs, falling rain, and sweltering heat. Here we start to bring our clues together to create a psycho-musicological profile. What kind of person would write like this? What level of personal confidence would drive a composer to venture into this territory when others around him were keeping their feet on the ground with common church sonatas and unprogrammatic concertos? Was he not afraid of being fired for writing outside of the main dogma, particularly since he was a priest employed by the state? We know that Mozart, Bach, and Beethoven encountered such pressures, and we know how they dealt with them. But what about Vivaldi?

By their unique and curious approach to musical expression, Vivaldi’s compositions reveal a part of his persona, and invite us to view him as a pioneer, not afraid to take chances, and with the artistic quality to pull them off in grand style. His concertos develop the technical abilities of the player, provide ample opportunity for musical expression, and almost always include at least one item of peculiarity to distinguish each work from its companions. They exhibit technical demands that would not be seen again in the oboe repertory for another 100 years, and which still create concerns for even the best performers of our own day.

For oboe players, Vivaldi’s concertos are in a class all their own. Performers find certain of these concertos technically daunting, even 300 years after they were written! What does this say about the oboists who performed them when they were new? Who were they, and how did they acquire the technical wizardry to play these works? We know Tomaso Albinoni (1871–1751) or Alessandro Marcello (1669–1747) could not have played them, otherwise they would have written such concertos themselves, or at least applied similar playing techniques. And if Albinoni, the most renowned oboe virtuoso in Venice, could not play them, then who did? The teenage girls (or younger!) at the orphanage, outcasts from society? If so, it is a great historical injustice that these girls remain practically unknown to us to this day.

Even the concerto in D minor, F. VII, No. 1 (tracks 16–18), arguably the simplest of the eight on this recording, contains difficult passage work and demands virtuosity and musicality far beyond the requirements of Albinoni’s most famous work (also a Concerto in D minor) or Marcello’s own D minor concerto. When we put these two composers’ famous concertos next to Vivaldi’s concertos F. VII, Nos. 6, 12, and 13, Vivaldi’s might as well have been written 100 years later, perhaps during the time of Mozart’s friends Friedrich Ramm (1744–1808) and Giuseppe Ferlendis (1755–1802), or even later, when Antonino Pasculli (1824–1924) redefined oboe technique much as Paganini did for the violin.

But Vivaldi’s mastery goes further. He seems to have been aware that a good teacher cannot bring out a student’s best potential without understanding that student’s particular psychological profile, limitations, goals, flaws, and special talents. And here is where we see that each concerto on this recording is significantly different, suggesting that the teacher Vivaldi carried his students through a learning process leading to a specific goal.

For analysis of this type we are hindered by our lack of information about Vivaldi’s personal life and that of his students. Still, listening to the Concerto in C Major, F. VII, No. 11 (tracks 9–12), note that the oboe soloist never plays the opening movement’s vigorous first theme. This is odd, although not totally unheard of. The introduction is supposed to set the stage for the solo instrument’s entrance, which normally features the same themes presented by the orchestra up to that point, or at least continues the spirit and musical approach of the orchestral introduction. In this case, however, the shy oboe soloist plays placidly, almost as if avoiding the confrontation that arises with the character of the first theme. Throughout the movement, the oboe keeps as far as possible from the impositions of the strings. In the second movement, the oboe begins and sets the tense and expressive tone. It is, again, interrupted by an imposing, forceful squad of strings, but manages, this time, to establish its own set of musical priorities. In the third and last movement, we encounter a remarkable closure, where the oboe soloist appears virtuosic and strong, and in the end even seems to challenge the dominance of the strings with the superiority and calmness of her phrasing. The personality established for the soloist since the beginning of the piece gains strength and confidence without actually transforming into something different. Once again, the oboe never plays the themes offered by the strings, which are forceful and imposing. Yet this time, the oboe appears able to sustain a more balanced dialogue, with its own themes, musical approach, and unique phrasing. As a teaching platform for a shy student, this concerto would be just the ticket to improving the player’s self-confidence and instrumental abilities simultaneously.

We will never know whether Vivaldi intended to employ didactic as well as compositional skills when he wrote this particular concerto, but it does make one wonder. We know he used music to explore more than just instrumental sound and that he was involved with opera and its treatment of emotion, theater, and story telling. So it’s certainly possible that Vivaldi put these skills together when writing concertos for specific pupils, eager to inspire them as best he could. Perhaps not all of his oboe concertos were written this way, and without more information about Vivaldi’s personal thoughts and teaching strategies, the possibility remains speculation. Nonetheless, on this recording I present the case that he did intend to use his diverse musical approaches as a teaching tool, designing each concerto for the overall growth of a student.

It is my honor to dedicate my performances on this recording to my long-forgotten colleagues who played these concertos originally, under Vivaldi’s tutelage. They remain some of the greatest oboe virtuosos ever to walk this earth, and it is a privilege for me to make their acquaintance through the only means left to us: the concertos Vivaldi wrote for them. We may never know their names, but we praise them nonetheless for their talent and superior achievement.

Album Details

Total Time: 75:00

Production Credits

Recorded September 1-3, 1993, Performing Arts Center, SUNY, Purchase, NY

Produced and engineered by Gregory K. Squires

Digital Editing: Wayne Hileman and Arlo McKinnon Jr.

Mastered by Wayne Hileman, Squires Productions, Inc.

Originally released in 1995 on the Musical Heritage Society label.

© 2010 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 7003