| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

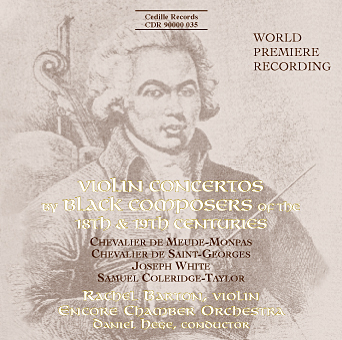

Violin Concertos by Black Composers of the 18th & 19th Centuries

Say “classical music,” and most people think of names like Mozart.

Cedille Records want the world to know about two of Mozart’s less-familiar contemporaries, Chevalier J.J.O. de Meude-Monpas and Chevalier de Saint-Georges, as well as later composers Joseph White and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. All were men of mixed African and European descent who made important contributions to European music in the 1700s and 1800s. Celebrities in their day, they’ve been all but forgotten in our era.

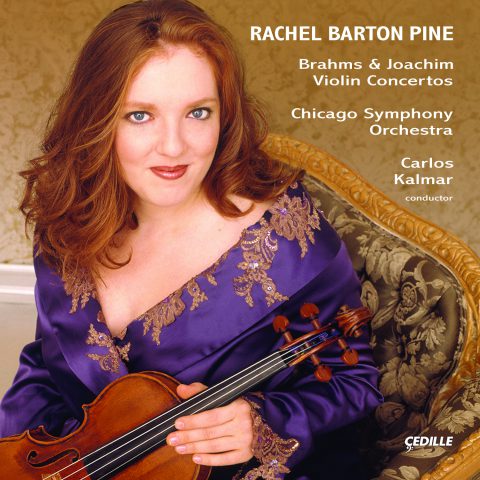

Performers are violinist Rachel Barton Pine, a celebrated performer who champions less well-known music, and Chicago’s Encore Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Daniel Hege. The Center for Black Music Research at Chicago’s Columbia College helped rediscover the musical compositions and locate the printed scores.

Relatively little is known of the early background of French composer Meude-Monpas, but we do know that he was born in Paris and was a musketeer in the service of French king Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette – when he wasn’t composing and writing books on music. Also active in Paris was Guadeloupe-born Saint-Georges, son of an aristocratic French plantation owner and an African slave. The dashing Saint-Georges (who graces the disc’s cover) was a champion swordsman and extraordinary athlete, as well as a violin virtuoso. In 1792, he was appointed colonel and commander of an all-Black military regiment of French Caribbeans and former American slaves.

Cuba’s Joseph White was born to a French businessman and an Afro-Cuban mother. A concert sensation in Europe and Latin America, White’s violin playing was admired by the finest musicians of his day, including the great opera composer Gioacchino Rossini, who wrote, “The warmth of your execution, the feeling, the elegance, the brilliance of the school to which you belong, show the qualities in you as an artist of which the French school may be proud.” When White performed in the US in 1876, one music critic called him “The best violinist who has visited this country . . .”

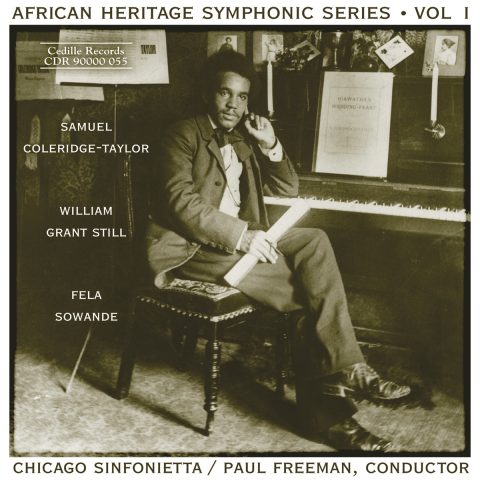

England’s Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the son of a physician from Sierra Leone and an Englishwoman, was esteemed in the US, especially among cultured African-Americans. His circle of American admirers included Booker T. Washington. The Coleridge-Taylor Society, a Black choral group, was founded in his honor in 1901. He visited the US several times and was a White House guest of President Theodore Roosevelt. His idol was famed Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, who encouraged the use of ethnic folk music, including Negro spirituals. Accordingly, Coleridge-Taylor incorporated elements of Black spirituals into many of his later works (although not the piece on this disc).

The CD booklet says the support of a European parent gave each of these mixed-race musicians access to formal educational and social opportunities unavailable to their African relations: “Excellent training and remarkable talents allowed these artists to take full advantage of a rare opening in the social fabric, yet they remained exotic and exceptional.”

“What may surprise people is that you don’t hear an obvious African influence in these pieces,” James Ginsburg, the CD’s producer, observes. “The composers approached Western music on its own terms and succeeded in creating outstanding works that show a personal imprint within the mainstream styles of their times.”

Preview Excerpts

CHEVALIER J.J.O. DE MEUDE-MONPAS (fl. c. 1786)

Violin Concerto No. 4 in D Major

(16:56)

CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES (1745-1799)

Violin Concerto in A Major, Op. 5, No. 2

(23:43)

JOSEPH WHITE (1835-1918)

Violin Concerto in F-sharp Minor

(21:34)

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR (1875-1912)

Artists

What the Critics Are Saying

“Music of great charm and elegance, rendered with sensitivity and stylish bravura by Barton.”

Artistic Quality 10/10 Sound Quality

“A disc you should not miss.”

“Barton, Hege, and [the Encore Chamber Orchestra] deliver attractive and involving performances with a Mozartean mix of subtlety and power.”

“Terrific performances; fine sound. A fascinating issue.”

“Compelling scores by four little-known composers who happen to be black… Rachel Barton handles the concertos’ varied demands with unaffected aplomb, performing this music lovingly rather than dutifully.”

Program Notes

Download Album BookletFrom Commodiyu to Creator: The Search for Social Equality Through Cultural Virtuosity

Notes by Mark Clague

Scholars have identified two possible and markedly contrasting derivations for the term “concerto.” Each of these has resonance for the musical and social parameters that surrounded the creation of the works on this recording. One school of thought emphasizes the contentious juxtaposition of soloist and ensemble by tracing the term to the Latin verb “concertare,” meaning “to fight” or “to contend.” Indeed, the concertos recorded here were and remain social weapons – tools created by their authors of mixed African and European descent to carve out a niche in a society of uncertain expectations.

A second line of reasoning traces the term through a variant spelling, “conserto,” to the root verb “conserere,” which in Latin means “to join together.” This derivation highlights the partnership between soloist and orchestra and by extension, composer and society. The goal of these four compositions was not revolution, but to create a place for social others within the existing fabric. The success of these compositions, therefore, rested not in a militant assertion of African sounds and symbols, but in their ability to seamlessly adopt the traditions and tropes of the Western European concert tradition. None of these works use African-derived melodies or rhythmic signatures. What these works do accomplish is to establish through cultural excellence the essential humanness of a race often reduced to commodity status by the slave trade. To be a composer was to be a creator, an artist, and a slave to no one. This is great music, stylistically similar to the violin masterworks of Mozart, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Wieniawski, or Sibelius. But these works are not simple imitations; they confront the Classical tradition and extend it, revealing the creative personality that is the artist and composer.

Although history has focused attention upon slavery and racial discrimination in the United States, the enslavement of Africans began in Western European society before it began in the colonies. In the fifteenth century, Portugese traders introduced slaves to Spain. Eventually the Dutch, French, Danish, Swedish, and English would participate in the commodification of this human cargo. Although there were many fewer blacks in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Europe than in the U.S., and thus racial conflict may have been less acute, blacks in Europe still faced a culture of discrimination. Each of the composers represented on this recording were of mixed African and European descent. Supported by their European parent, these individuals gained access to educational and social opportunities unavailable to their African relations. Excellent training and remarkable talents allowed these artists to take full advantage of a rare opening in the social fabric, yet they remained exotic and exceptional.

The concerto strikes at one of the core values in Western European musical aesthetics: virtuosity. While in its beginnings during the Baroque, the concerto featured a small ensemble or concertino group as often as the individual, by the Classical period the term came to signify a work for solo instrumentalist and orchestra. The uncommon skill and accomplishment of these black artists allowed them to give musical voice to their ideas. Whether in reference to technical skill or poetic expression, to performance acumen or compositional genius, virtuosity serves to focus attention upon the exceptional individual.

The inspiration for this recording began in 1992 when the Civic Orchestra of Chicago and its conductor, Michael Morgan, asked Ms. Barton to perform Meude-Monpas’s Concerto No. 4 in D Major as part of a concert of music by black composers. Programmed alongside premieres of twentieth-century American works by Ed Bland, Gary Powell Nash, and Henry Heard, as well as Hale Smith’s Innerflextions and Alvin Singleton’s Sinfonia Diaspora, the eighteenth-century violin concerto sparked Ms. Barton’s interest in the possibility of discovering other unknown European Classical gems. With the help of Dominique-René de Lerma, a leading authority on black music, she became aware of a small but select group of black violin virtuosi active over the past two and a half centuries: Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799), George Bridgetower (1780-1860), to whom Beethoven originally dedicated his Kreutzer Sonata, Joseph White (1835-1918), and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), who played the violin but was better known as a conductor and composer. Although it is likely that he too was a performer, too little is known about Le Chevalier J.J.O. de Meude-Monpas to be certain. Two American black virtuosi also deserve mention, Joseph Douglass (1871-1935), grandson of author and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and Clarence Cameron White (1880-1960) who studied violin with Douglass and composition with Coleridge-Taylor. Many considered C.C. White the leading black violinist of the early twentieth century.

According to music scholar Gabriel Banat, little might be known of the exploits of the Chevalier de Saint-Georges if not for his undisputed prowess with a foil. While the composer’s biographers were prone to elaborate mythologizing, the chroniclers of Saint-Georges the fencing master were much more precise and trustworthy. Born in 1745, Saint-Georges inherited his name and title from his father, Joseph Jean-Marie Boulogne, a noble French plantation owner. Saint-George’s mother, Nanon, was an African slave from the island of Guadeloupe in the Antilles. Nothing is known of his early musical training, but Saint-Georges was given the broad Classical training of a European nobleman that undoubtedly included musical study. It was not unusual that this child of a slave would be accepted as his own by his white father. According to André Maurois, “It was customary that colons return to France with their sons of semi-African blood, leaving their daughters in the islands.”

In 1755, M. de Boulogne de Saint-Georges returned with his 10-year-old son to Paris. The boy may have studied violin with Jean-Marie Leclair and Françoise Joseph Gossec, but the first reliable evidence of his musical career dates from 1769 when he became concertmaster of Gossec’s orchestra, the Concert des Amateurs. Based upon the dedication of Saint-Georges’s trios, Gossec, an important figure in the development of the French symphony, is considered to have been his composition teacher. When Gossec left to direct the Concert Spirituel in 1773, Saint-Georges assumed the leadership of the orchestra and dedicated himself to a career in music. In 1776, Saint-Georges joined forces with “a consortium of capitalists,” aspiring to become co-director of the Academie Royale de Musique, later known as the Paris Opéra. He lost the chance for the position when three ladies in the company petitioned the queen for his rejection, claiming their honor would be compromised if they had to take orders from a mulatto. While little-known today, Saint-Georges was a prominent musician and popular performer in his day. Composers such as Gossec, Karl Stamitz, Antonio Lolli, and J. Avolio dedicated compositions to the virtuoso. Including eight operas, ten violin concertos, and 115 songs, the more than 236 compositions credited to Saint-Georges give some indication of his impact upon the Parisian music scene. Saint-Georges was especially influential in the development of the Sinfonie Concertante, a genre featuring multiple soloists, usually two violinists, and orchestra.

As with all of his concerti, Saint-Georges’s Concerto for Violin in A Major, Op. 5, No. 2 (ca. 1775) serves as a bridge from the virtuosic works of Baroque violinist/composers such as Corelli, Locatelli, and Tartini, to those of nineteenth-century virtuosi such as Vieuxtemps and Wieniawski. Although influenced by the more conservative writing of the Mannheim symphonists such as Johann Stamitz, Saint-Georges was both a performer and a showman. His virtuosic emphasis of the upper register, for example, extends five pitches higher than any of Mozart’s (exactly contemporaneous) violin concerti. Saint-Georges also took full advantage of recent developments in bow technology to emphasize fleeting and precise passagework. Around 1750, French bow makers including Thomas Dodd the elder and Françoise Tourte l’aîné inverted the usual curve of the bow, forming a concave shape that produced stronger and more aggressive tones in the upper portions of the bow.

Following the traditional fast-slow-fast plot, Saint-George’s concerto is in three movements. By far the longest movement, the opening Allegro Moderato is in a modified sonata form that lacks a recurring first theme stated unequivocally in the tonic key. While melodic ideas are repeated and passed from orchestra to soloist and back, Saint-Georges seems to possess a limitless melodic imagination. His melodies are often in two markedly contrasting four-measure segments whose distinct personalities are underscored by shifts from soft to loud. His writing is vigorous and intended to maximize virtuosic impact. Rather than develop small melodic ideas into larger ones, Saint-Georges provides a series of independent melodies. The orchestral motif that begins the piece, for example, never comes back. Likewise, the soloist’s initial melody is not prefigured by the orchestra as would be typical in Mozart’s concerti (although that theme does return in the recapitulation). The soloist is also the only musician to play triplets in this movement. Throughout the work, orchestra and soloist retain their distinct melodic identities, sharing some material but also claiming certain motifs as uniquely their own. It is really a duo concerto for soloist and orchestra. One of the orchestra’s signature motifs is based on the medieval hocket or “hiccup” technique of alternating a motive between two instrumental voices, in this case an off-beat figure bouncing between first and second violins. Excepting brief turns to the minor mode and some chromatic passagework, Saint-Georges’s harmonies are straightforward. He makes wonderful use of texture, balancing melody and accompaniment with polyphonic interplay and unison writing.

Lilting triplets from the orchestra announce a shift in character for the second movement, a Largo which, despite its somber mood, is in the key of D major. Again Saint-Georges strikes a remarkable balance between unity and variety in this lyric interlude. Tying this movement to the previous is the soloist’s theme which, as in the first movement, begins with a long held note that blossoms into a lyric gesture. Saint-Georges borrows a technique from the Baroque concerto grosso by frequently restricting his accompanying ensemble to a small treble group of violins. The bass instruments’ return creates a powerful sense of depth and variety within the limited context of an all-string orchestra.

The Rondeau form is perfectly suited to Saint-Georges’s gift for melodic invention. An opening eight-measure theme serves as a recurring touchstone for the composer’s melodic fantasies and vibrant sense of humor. As with the second movement cadenza, each of the Eingangen or improvised melodic introductions recorded here were composed by Ms. Barton based upon themes from within the movement or from stylistically appropriate ornamental devices. The final movement brings the virtuoso display to a dramatic crescendo – a display that Ms. Barton intensifies with additional ornamentation, especially trills.

The only comprehensive evidence that survives concerning the life and work of the Chevalier J.J.O. de Meude-Monpas is in his music. Eileen Southern’s groundbreaking biographical research into black composers reveals only that Meude-Monpas was a musketeer in the service of Louis XVI of France who went into exile with the onset of the French Revolution. The eighteenth-century composer was born in Paris and died in Berlin, but his precise dates remain unknown. He studied music in Paris with Pierre La Houssaye and Françoise Giroust and published six concertos for violin (1786) as well as two books on music. While written only about eleven years after the Saint-Georges concerto and in a similar French Classical idiom, the stylistic gulf that separates the two is impressive. The later concerto lacks much of the virtuosic fire of the Saint-Georges, but evokes a broader range of emotion and dramatic intensity. Meude-Monpas’s use of wind instruments in the orchestra also produces a markedly different overall effect. Yet, both concerti are constructed in much the same manner. Both have three movements: an allegro, a slow movement, and a rondo. Both lack the traditional first movement cadenzas of the German tradition, but contain opportunities for improvisation in the second movement. Their broad structural similarities likely represent an historically elusive French concerto tradition, yet the many more subtle parallels in the treatment of themes suggest the possibility that Meude-Monpas might have known the work of Saint-Georges. In both first movements, for example, the use of triplet figures in the solo part set against an immutable duple accompaniment seems more than coincidental.

The opening Allegro of Meude-Monpas’s fourth concerto makes dramatic use of silence, likely under the influence of the early symphonists. The whole concerto reveals a polish of craft and a fine attention to orchestration. Here, the soloist and orchestra are partners, not competitors. The orchestral writing is so clear and unencumbered that the soloist never gets lost within the din of the musical argument. While not indulging in a show of technical difficulty, Meude-Monpas still allows the soloist to shine – he increases the violinist’s range beyond even Saint-George’s concerto, for example, by using ever higher pitches to highlight his themes. While limited to the four-square melodic phrases of the Classical style, Meude-Monpas gives the illusion of a more lyric, almost romantic sensibility. Saint-Georges used dynamics to add contrast, but Meude-Monpas blends each phrase into its successor producing eight measure paragraphs with pairs of four measure sentences. Frequent internal repetitions invite the soloist to add echo effects which help draw the listener into the work.

In the second movement, Adagio, the composer makes use of strong dynamic contrast primarily as an emotional resource. The halting quality of the slow dotted rhythms followed by rests sets up a melodic tension that drives into suddenly loud descents. Meude-Monpas also uses soft pianissimo markings to advantage, understating rather than overstating his dramatic conception. The lively Rondo: Allegretto Poco Presto serves as a cathartic foil to the pathos of the middle movement. Its skipping staccato theme is first presented by the soloist and only then imitated by the orchestra. The movement develops into a five-part structure, ABACA, in which the A section/rondo theme is repeated verbatim. The B section features the violin soloist while the C section includes some of the only polyphonic interplay in the work. Here the orchestra takes over the melodic role, while the soloist presents a rapid-fire and arpeggiated countermelody.

Born in Matanzas, Cuba to a French businessman and Afro-Cuban mother, José Silvestre de Los Dolores White y Lafitte (Joseph White) made his public debut at age 18 performing a fantasy on themes from Rossini’s William Tell along with two pieces of his own. His accompanist was the most celebrated North American pianist and composer of the day, Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869). Gottschalk encouraged White to pursue further training in Paris and raised the money to send him there. Overcoming 60 rival applicants to the Paris Conservatoire, White won the opportunity to study with Jean-Delphin Alard, the pre-eminent master of the French school of violin playing, as well as Henri Reber and Ferdinand Taite. In 1856, he won the Prix de Rome in Violin and two years later began touring Europe, the Caribbean, South America, and Mexico. Gioacchino Rossini, living in France in retirement, wrote a letter of praise to the young virtuoso dated November 28, 1858: “The warmth of your execution, the feeling, the elegance, the brilliance of the school to which you belong, show qualities in you as an artist of which the French school may be proud.”

While living in Madrid in 1863, White was awarded the Order of Isabella la Catòlica by the Spanish court. White taught at the Paris Conservatoire from 1864-65 as a temporary replacement for Alard, and his Six études pour violon, op. 13 were approved as standard teaching materials for the school. He made his U.S. debut during the 1875-76 season, performing two concerts with the Theodore Thomas orchestra in New York. A reviewer at a Boston recital that same year exclaimed, “His style is perfection itself, his bowing is superb, and his tone exquisite…. His execution is better than Ole Bull’s, he possesses more feeling than Wieniawski, the volume of his tone is greater than that of Vieuxtemps.” For about ten years, White worked for the Imperial Court in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, but he resettled in Paris in 1891 where he spent the remainder of his life. Approximately thirty two of his works have survived in published and or manuscript form.

Composed in 1864, at the beginning of White’s touring career, the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in F-sharp Minor follows the standard three movement plan: Allegro, Adagio ma non troppo, and Allegro moderato. Although quite colorful and sonorous, the choice of F-sharp minor for a violin concerto is curious. F-sharp is a rare, but not unheard of, key for violin concertos. In fact, White’s choice may signal a competitive stance toward two of his contemporaries, composer/virtuosi who also authored concerti in this key in the early 1850s: Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1814-1865) and Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880). White himself performed the solo part for his concerto’s 1867 premiere in Paris. A critic described the piece as “one of the best modern works of its kind… The fabric is excellent, the basic thematic ideas are carefully distinguished, the harmonies are elegant and clear, and the orchestration is written by a secure hand, free from error. One feels the presence of a strong and individual nature from the start. Not a single note exists for mere virtuosity, although the performance difficulties are enormous.” The work’s American premiere did not occur until 1974, when violinist Ruggiero Ricci performed the concerto with the Symphony of the New World, Kermit Moore conducting, in New York’s Avery Fisher Hall.

Written after Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840) had redefined the standards of violin performance, White’s concerto is by far the most virtuosic of the works on this recording: frequent double stops often in parallel octaves and rippling arpeggios that traverse the entire range of the violin in just a few beats characterize the work. The opening movement is in a straightforward sonata form. The first theme appears at the onset of the work in the orchestral violins’ melody while the second theme is presented initially by the clarinet. White’s treatment of the development section is rather ingenious as he imitates the sparse and free recitative texture of opera, resulting in a spontaneous and dramatic cadenza-like delivery. The coda’s simple horn melody helps relax the aggressive virtuosity of the first movement and sets up the beginning of the second movement, which follows without a break. Cast in an ABA ternary form, the Adagio ma non troppo features a lyric violin melody characterized by wide leaps and angular rhythms that enliven the slow tempo. The central Animato section adds intensity and drama to the argument before the return of the A theme. The rolling grace of the cadenza’s passagework belies its difficulty. An ethnically-flavored, almost Hungarian or gypsy-like theme for the rondo finale propels the listener on a journey through a series of enchanting dances, culminating in a bombardment of virtuosic cadential pyrotechnics.

Although he was born in Holborn, near London, and lived in the English town of Croydon, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor became increasingly involved in racial politics in the United States as a symbol of the New Negro, a full cultural and social participant in American life. In 1905, Booker T. Washington hailed Coleridge-Taylor as “the foremost musician of his race” and “an inspiration to the Negro, since he himself, the child of an African father [from Sierra Leone], is an embodiment of what are the possibilities of the Negro under favorable environment.” Although Coleridge-Taylor became aware of African-American musics in 1897 and often followed Dvorák’s call to include melodies from Negro spirituals in his work, the Romance appears to bear no relationship to black musical materials. While not remembered primarily for his violin playing, Coleridge-Taylor presented the premiere of his Romance in G Major, Op. 39 in the year of its composition (1899) accompanied by his wife, Jessie, at the piano.

Written in one continuous movement, the work eschews technical display in favor of lush harmonic and melodic beauty. The virtuosity of this work is compositional, rather than instrumental. The Romance is by far the most harmonically sophisticated and thematically complex composition of the four included here. To help sustain his lengthy and slow melodic essay, Coleridge-Taylor adopts one of the strongest and most economical musical forms: sonata form. Theme one appears in the violin solo at the beginning of the work. Following an extended transition that modulates to D major (the dominant of G) through both B major and B-flat major, the composer presents theme two in the solo voice using double stops (two pitches performed simultaneously). A faster Animato section presents the development in which theme one is transformed into a stormy motive primarily through acceleration and melodic ornamentation. The orchestra restates theme two briefly before the recapitulation presents both themes through the voice of the solo violin. A short coda reiterates the first theme in a gesture of apotheosis that brings the work to a close in the upper reaches of the violin’s tessitura.

Mark Clague is an Adjunct Associate Professor of Musicology and Music History at The University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) and Executive Editor of Music of the United States of America (MUSA), a series of scholarly editions of American music administered by the American Musicological Society and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

References:

Banat, Gabriel. “Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges, Man of Music and Gentleman-at-Arms: The Life and Times of an Eighteenth-Century Prodigy.” Black Music Research Journal. 10, no. 2 (Fall, 1990): 177-212.

de Lerma, Dominique-René. “Black Composers in Europe: A Works List.” Black Music Research Journal. 10, no. 2 (Fall, 1990): 275-334.

Floyd, Samuel, editor. International Dictionary of Black Composers. (forthcoming) Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998.

Green, Jeffrey. “‘The Foremost Musician of His Race’: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor of England, 1875-1912.” Black Music Research Journal. 10, no. 2 (Fall, 1990): 233-252.

Southern, Eileen. Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Wright, Josephine. “Violinist José White in Paris, 1855-1875.” Black Music Research Journal. 10, no. 2 (Fall, 1990): 213-232.

Publishers

Concertos by Meude-Monpas and Saint-Georges: forthcoming editions by Rachel Barton.

White: Concerto in F# minor: orchestral score and parts are available from Kermit Moore, New York, NY. Violin and piano score published by Belwin Mills, Miami FL.

Coleridge-Taylor: Romance in G Major: Orchestral score and parts, and score for violin and piano are available from the Fleischer Collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia, PA.

About the Violin

Rachel Barton plays the ex-Lobkowicz Antonius & Hieronymous Amati of Cremona, 1617, on generous loan from her patron.

The Seal of the Lobkowicz Family on the back of the violin identifies it as one of the instruments held by this illustrious European family. Prince Lobkowicz was a significant patron of Beethoven.

The Amati family is responsible for the violin as we know it today. Andreas Amati invented the violin c. 1550. His sons Antonius and Hieronymous, known as the Brothers Amati, brought violin making forward into the 17th century. Hieronymous’s son Nicolo continued to nearly the end of the 17th century and was the teacher of Andreas Guarneri and Antonio Stradivari.

The violin Miss Barton plays is a particularly fine example of the makers’ work and is excellently preserved. The top is formed from two pieces of spruce showing fine grain broadening toward the flanks. The back is formed from two pieces of semi-slab cut maple with narrow curl ascending slightly from left to right. The ribs and the original scroll are of similar stock. The varnish is golden-brown in color.

Album Details

Total Time: 75:17

Recorded: June 3-5, 1997 at the Chapel of St. John the Beloved, Arlington Heights, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Lawrence Rock

Production Assistant: David Dieckmann

Cover: Anonymous etching based on a painting of Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Mark Clague

Violin: “ex-Lobkowicz” A & H Amati, Cremona, 1617

© 1997 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 035