| Subtotal | $38.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $3.90 |

| Total | $41.90 |

Store

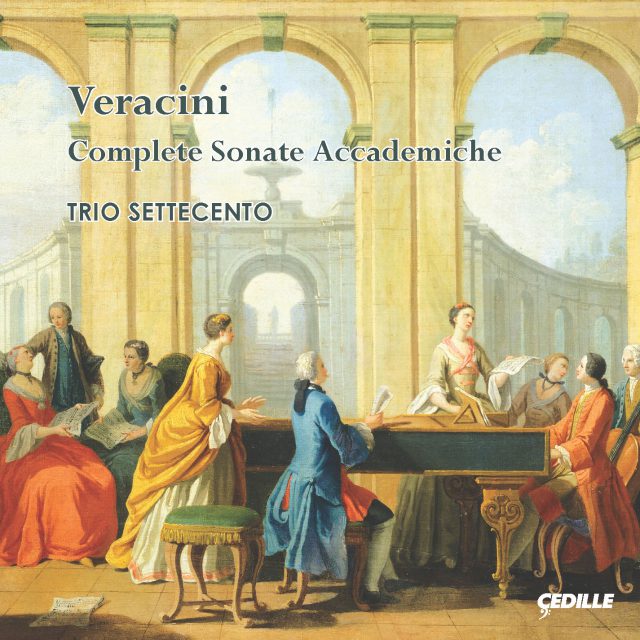

Trio Settecento, the “superlative Chicago-based early music ensemble” (Gramophone) presents Italian Baroque composer Francesco Maria Veracini’s monumental Opus 2 Sonate Accademiche for violin and continuo. It’s a cosmopolitan collection of 12 sonatas of breathtaking scope and pan-European influences — a set of sonatas unlike any other of the era. Veracini’s Sonate Accedemiche is both an homage to his fellow-countryman Arcangelo Corelli and an original masterpiece in its own right.

Billboard chart-topping violinist Rachel Barton Pine, “one of the rare mainstream performers with a total grasp of Baroque style and embellishment” (Fanfare) and her colleagues in Trio Settecento, cellist John Mark Rozendaal, and harpsichordist David Schrader, bring their “refreshing, life-enhancing Baroque playing” (Chicago Tribune) to these sonatas infused with melodies imported from Scotland, Dalmatia, Poland, the Canary Islands, and rural France.

Preview Excerpts

Sonata No 1 in D major

Sonata No 2 in B-flat major

Sonata No 3 in C major

Sonata No 4 in F major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletVeracini Complete Sonate Accademiche — Sonatas for Violin and Continuo, Op. 2

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

Francesco Maria Veracini (1690–1768) was the foremost figure in a generation of renowned virtuosi, including Giuseppe Tartini (1692–1770), Pietro Locatelli (1695–1764), and Jean-Marie Leclair (1697–1764), who revolutionized the art of violin playing in the early 18th century. All four of these figures dazzled audiences throughout Europe with their astonishing performances. They raised the bar for instrumental soloists with their prolific production of fine and difficult music for the violin, works that daringly expanded the compass of expression and acrobatic performance on the instrument. Veracini’s place as leader of this violinistic ‘rat pack’ ism suggested by the fact that both Locatelli and Tartini, though only slightly younger, took inspiration from his playing and teaching, and Leclair’s path-breaking mature works are in turn, indebted to Locatelli. Veracini’s achievement is crowned and his legacy best preserved in his Opus 2 of 1744, the set of twelve Sonate Accademiche, a work of uniquely varied inspiration and majestic scope.

Appearing after a 23-year gestation (Opus 1 was published in 1721), the sonatas of Veracini’s Opus 2 represent a zenith of the genre, on a scale of sheer length attempted never before and not soon after. These sonatas are fully half again as long as their nearest rivals (the sonatas of Tartini and Locatelli) and they explode the possibilities of the genre, essaying a variety of designs and content unlike any other sonata collection of the era.

Homage

While Veracini was the vanguard of his generation, the artistic father of the entire cohort was Arcangelo Corelli, whose sublime Opus 5 (Rome, 1700) was the model for dozens of sonata collections published in the 18th century. In fact, his book of twelve sonatas seems to have become virtually a de rigueur format for ambitious violinists, with notable contributions to the genre coming from Locatelli, Leclair, Tartini, Vivaldi, Rebel, and a host of lesser lights. All of them owe more or less to the forms, sonorities, and attitudes found in Corelli’s Opus 5 sonatas. In no publication is this indebtedness greater, more clearly acknowledged, or more fully repaid than in Veracini’s Opus 2, Sonate Accademiche, a book that is both a monumental homage to Corelli and an original masterpiece in its own right.

The first clue that Veracini is responding to Corelli is that Veracini has reproduced the sequence of keys found in Corelli’s sonatas. In each book, the first sonata is in D major, the second in B-flat major, the third in C major, and so on without exception straight through to the 12th sonata in D minor. Each book is divided into two parts, the first halves containing six sonate da chiesa (in which fugal textures predominate), the second parts comprised of sonate da camera (containing more dance movements). Looking more closely, we find many of Veracini’s ‘Academic’ sonatas contain clever hat-tips, large or small (but never slavish), addressed to their parallel numbers in Corelli’s collection.

Both composers open their sonatas number one with pseudo-improvisational exordia formed of brilliant arpeggios through the full range of the violin, played in D major, one of the instrument’s most characteristically resonant and celebratory keys. This opening serves as a sort of throat clearing in which the violinist as orator tests and introduces her voice, gets the listeners’ attention, and announces something of the scope and ambition of the project being undertaken. Both sonatas place their most significant content in pairs of closely related fugues, one in common time (4/4), the second in compound (6/8) meter. These fugues, so placed, signify the composers’ commitment to one of the most rigorous and disciplined modes of musical composition, imitative counterpoint, a technique so high-minded that its sound, then and now, was and is deployed to invoke the sacred. Veracini stressed this intention by titling his fugues ‘Capricci,’ and giving them a continuous numerical sequence throughout the book. Thus, because the first sonata contains two capricci, the Capriccio Terzo is located in sonata number two, the fourth capriccio in sonata number three, and so on. The word ‘capriccio’ is one of a number of words that could designate a fugue, including ‘ricercar’ (as in J. S. Bach’s Musical Offering) and ‘contrapunctus’ (Bach’s Art of the Fugue). Among the options, Veracini chose the one that suggests the particularly wild and playful qualities of his personal invention (invention is yet another name used for fugues of the period). It bears noting that Veracini’s work, appearing in 1744, was coming into a world that had largely left this idiom behind, favoring the lighter, dance-inspired style gallant. However, he had an ally in his sometime neighbor J.S. Bach, who was revising and refining his final contrapuntal magnum opi in the same years that saw Veracini’s completion of his Opus 2.

The affect, movement, and contour of the opening gesture of Corelli’s Op. 5, No. 3, one of his most beloved lyric creations, are subtly recalled in the Largo, e nobile of Veracini’s Op. 2, No. 3. The opening of Veracini’s Op. 2, No. 4 is motivically derived from Corelli’s opening to his Op. 5, No. 4. In Corelli’s Op. 5, No. 5 the key of G Minor evokes craggy, expressionistic motifs of large jagged intervals in surprising sequences, an effect Veracini exaggerates in his G minor sonata. In each composer’s Sonata No. 6, a penultimate movement in F-sharp minor opens with the poignant motif of a rising third followed by a larger descending interval; and concludes with a joyous fugue in compound meter.

In the E-major sonata pair (Nos. 11) one of Veracini’s clearest and wittiest compliments to his model occurs when he repeats the final phrase of his Minuet with an unusually long slur, echoing a gesture found in Corelli’s Gavotte.

And finally, Veracini answers Corelli’s number twelve, the justly famous variations on La Folia, with a sonata containing a passacaglia and a chaconne, two variation forms also derived from the Spanish viheula da mano tradition.

A Tale of Three Cities

The famous musical diarist, Charles Burney observed that, “by travelling all over Europe [Veracini] formed a style of playing peculiar to himself.” Indeed the Sonate Accademiche display a rich pan-European variety of influences. Included and assimilated are tunes and topoi imported from locales as far-flung as Scotland, Dalmatia, Poland, the Canary Islands via Spain, and rural France by way of London. The worldly and well-travelled F.M. Veracini’s career flourished especially in three vibrant European cities: Florence, Dresden, and London. These three cultural milieus each contributed particular qualities to Veracini’s compositions for the violin.

Veracini was born and educated in Florence, an ancient cultural capital of the Land of Music, a city with a famous history of nurturing the arts with a seriousness of purpose and a specific brand of Humanism that subsumes both virtuosity and sensuality. Growing up in a family of literate professionals schooled in Latin and Greek, and passing daily through streets overlooked by the knowing gazes of saints and heroes sculpted by Donatello and Michelangelo, one may also imagine that the young Francesco Maria learned early the potential for dignity and urgent action in the vocation of an artist. And one may also imagine such a vision moving the young man to strive mightily for transcendent mastery in the arts of counterpoint, harmony, and invention (as well as violin playing). Every page of the Sonate Accademiche is forged of a characteristically Tuscan alloy of discipline, ambition, and sprezzatura.

The most famous anecdote of Veracini’s career tells us that the violinist’s injurious self-defenestration from an upper story window in Dresden was the result of mental instability caused by arduous study of music and alchemy. The implications are intriguing. Throughout the period known as the baroque era in music, various forms of alchemy flourished sporadically in central Europe. These late expressions of renaissance magic sometimes appeared as symbolic spiritual disciplines, at other times as a coarser pursuit. Alchemy was the study of processes of transformation with the object of changing common materials into real or metaphorical (spiritual) gold. One material manifestation of the discipline is Dresden’s famous porcelain industry which literally uses chemical processes to turn dirt (clay and minerals) into gold (money). One of the more spiritual approaches is found in music, an art known from earliest history for its power to transform minds and spirits. This effort is explicit in such a work as Michael Maier’s collection of magical emblems and fugues, Atalanta fugiens (Oppenheim, 1617). It is implicit in fugues of many German composers (Bach and Buxtehude being the most famous exemplars): compositions in which arcane knowledge is brought to bear on complex thought challenges, sonically indicated by musical subjects of mystical abstraction and strangeness. These pieces often feature chromatic intervals in which tones of the natural scale are altered, and employ an array of procedures to develop their subjects, including temporal compression or expansion, dissection, mutation, transposition, juxtaposition, and inversion. These mathematical techniques are the tools of an aural art with a sur-prising power to transform the listener. Veracini’s fugues, with their long chromatic themes and serious working-out of materials, owe much to their German counterparts. Thus Veracini and his Lutheran colleagues join Doctor Faustus and Dürer’s Melancholia in turning to the numerical/spiritual arts of the quadrivium (harmony, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy) to address problems of the soul that seem rarely to have troubled musicians based south of the Alps.

In London, Veracini’s career thrived in the most modern commercial capital in the world, where the public concert scene was rapidly developing into the cosmopolitan phenomenon we still inhabit. The competitive nature of this environment gave license and even added incentive to Veracini’s innate enthusiasm for the sheer entertainment value of violin virtuosity. Veracini never writes flashy trash, but he also never holds back, ever willing to dazzle and delight his audience with giddy pyrotechnics. Veracini also addresses a ticket-buying public with a particularly British way of assimilating popular, even rustic tunes into high art music. He never heard their music, but in England Veracini was breathing the same air and drinking the same water as William Byrd and Ralph Vaugh Williams.

Two sonatas feature traditional tunes Veracini almost certainly heard in per-formances of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera. The theme of the Cottillon Capriccio Quinto in Veracini’s Sonata Quarta is derived from a French tune performed in the famous ballad opera with the English text, “Youth’s the season made for joys.” This tune appears to be the ur-cottillion: the name of the dance comes from a line in the tune’s French text, “Ma commere, quand je danse, Mon cotillion va-t-il bien?”

The Scottish tune featured in the theme and variations of Sonata No. 10 is‘Tweedside,’ sung in the Beggar’s Opera by Polly Peachum with the text, “The stag, when chas’d all the long day . . . ”

London was also the scene of Veracini’s career as an opera composer, which included three productions for the Opera of the Nobility, the company the Prince of Wales established to compete with Handel’s Royal Academy. An operatic manner of presentation can often be detected in the slow movements of Veracini’s Opus 2, especially in Sonatas 2 and 10.

The Sonate Accademiche collection concludes with a brief two-voice canon, setting the second half of an epigram-matic Latin text:

Cur adhibes tristi numerous cantumque labori?

Ut RElevet MIserum FAtum SOLitosque LAbores.

Why do you apply numbers and song to grievous labor?

That it may relieve wretched fate and accustomed labors.1

This text is first found in a music manual of 1591 by Adam Gumpelzhaimer, and subsequently appears on the title pages of many continental musical publications. It seems a fitting peroration for a book whose many pleasures and lessons were created, and are only realized, by dint of extraordinarily hard work.

Acknowledgements

Trio Settecento wishes to thank Christophe Landon for the generous loan for use in this recording of a cello made by David Tecchler in Rome in 1705. This extraordinary instrument is thought to be the only Tecchler cello to survive unaltered in size and with its original neck.

1 Translation by Leofranc Holford Strevens, quoted by Benjamin Hebbert in “Nicolas Lanier 1588–1666 A Portrait Revealed.”

Album Details

Total Time: 186:48

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing: Jeanne Velonis

Technical Editing: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

Cover Painting: Allegory of arts, Music, c. 1751-1752, by Giuseppe Zocchi (1711-1767) oil on canvas / De Agostini Picture Library / A. Dagli Orti / Bridgeman Images

Recorded: Sonatas 7-11: August 21-23, 2013; Sonatas 1-6, 12, and Canone: August 4 and 6-10, 2014, in Nichols Concert Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago, Evanston, Illinois

Instruments:

Violin: Nicola Gagliano, 1770, in original, unaltered condition

Violin Strings: Daniel Larson, Gamut Music

Violin Bow: Louis Bégin, replica of 18th -century model

Cello: 1705 David Tecchler, lent by Christophe Landon

Cello Bow: Julian Clarke

Treble Viol: Clarke Gaiennie (used for Canone: Ut relevet miserum)

Treble Bow: Christopher English

Harpsichord: Willard Martin, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1997. Single-manual instrument after a concept by Marin Mersenne (1617), strung throughout in brass wire with a range of GG-d3.

Tuning: Unequal temperament by David Schrader, based on Werckmeister III

© 2015 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 155