| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

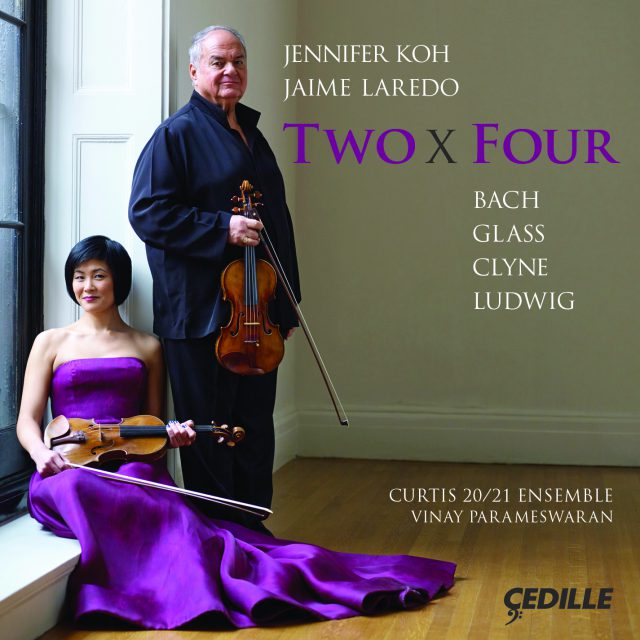

Renowned violinists Jennifer Koh and her distinguished mentor Jaime Laredo illuminate captivating connections between student and teacher, and composers across the centuries, in Two x Four, an album of four double-violin concertos, performed with the Curtis 20/21 Ensemble conducted by Vinay Parameswaran.

The compositional touchstone is J.S. Bach’s Violin Concerto in D minor, BWV 1043, an innovative work that introduced new ways for two solo violins to converse with each other and with orchestra.

Koh and Laredo leap from the Baroque to the late 20th-century for Philip Glass’s attractive, hypnotically undulating Echorus on the theme of compassion. It was written for the great Yehudi Menuhin and his protégé, Edna Mitchell.

Two new works commissioned expressly for the project receive world premiere recordings. Anna Clyne’s impressionistic Prince of Clouds is “a winner . . . . This is music one can listen to again and again and find new things to appreciate each time” (Chicago Tribune). David Ludwig’s evocative Seasons Lost, a contemporary counterpart to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, is “full of beautiful ideas contrasting with playful/menacing Vivaldian gestures” (Philadelphia Inquirer).

Preview Excerpts

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)

Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043

ANNA CLYNE (b. 1980)

PHILIP GLASS (b. 1937)

DAVID LUDWIG (b. 1974)

Seasons Lost for two violins and string orchestra

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletTwo x Four

Notes by Katherine Bergstrom after a video interview with Jennifer Koh and Jaime Laredo

The Two x Four project stems from a humble premise — two violinists performing the work of four composers. The project is not intended to focus merely on the performative aspect of music, however. Two x Four celebrates a tremendous collaboration between violinists Jennifer Koh and Jaime Laredo, a partnership that began when Koh was Laredo’s student at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. While Laredo is quick to point out that their relationship has since developed to that of colleagues, Koh’s reverence for Laredo as a life-long mentor is obvious in the duo’s work.

Preparations for Two x Four began in 2010, when Koh approached composers Anna Clyne and David Ludwig about creating new concertante works for two violins, an instrumentation choice inspired by one the most cherished pieces in Koh’s repertoire: Bach’s double violin concerto (Concerto in D minor, BWV 1043). Koh first performed this piece with Laredo while still a student at Curtis, and it has stayed with her as a reminder of the generous dialogue between student and mentor. In asking Clyne and Ludwig to compose for two violins, Koh and Laredo continue their dialogue in homage to the tradition of Bach’s double, reinforcing the collaboration that the Two x Four project commemorates.

Over the next year and a half, Clyne and Ludwig worked with Koh to compose pieces that reflected the special partnership between her and Laredo. For Clyne, this meant finding each player’s individual voice within the context of the larger piece, deconstructing the ensemble and rebuilding it through the players’ musical relationship. For Ludwig, connecting to the tradition of the Bach double concerto was a compelling point of departure, allowing him to respond through composition to the relationship portrayed by Bach, and the relationship of the two violinists before him.

Koh encourages listeners to consider the performance tradition represented in the works on Two x Four. The two new compositions, Clyne’s Prince of Clouds and Ludwig’s Seasons Lost, both follow in the structural footsteps of Bach, nearly 300 years after he wrote his double violin concerto. The compositional dialogue between past and present resonates throughout this program, not only in reverence to the spirit of Bach, but as reassurance of his relevancy in the future.

Bach — Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043

From 1717 to 1723, Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) served as the Kapellmeister (music director) for Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen. The position of Kapellmeister at this time in the late Baroque period typically entailed composing sacred cantatas or masses for use in religious services. Prince Leopold was a Calvinist, however, so he did not require extravagant music for worship. Instead, Bach was free to compose without the limitations of sacred texts. With the support of the music-loving Leopold, Bach undertook an extensive foray into secular music. It was during these years that Bach produced some of his most celebrated compositions, including the Concerto for Two Violins in D minor.

Although the beloved “Bach Double,” as it has become known, may have been a product of circumstance, it was also an inventive move away from traditional compositional form. Broadly speaking, Baroque concertos can be sorted into two categories — the solo concerto, which features a single soloist accompanied by a larger orchestra, and the concerto grosso, which features a concertino (a group of multiple soloists) playing opposite the ripieno (full orchestra). Bach’s double violin concerto defies this categorization, however, and combines aspects of both forms to create a unique set of musical relationships throughout the piece. While Bach was not the first to write a double concerto, his contribution to the genre is intricately composed, creatively pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a solo moment. At some points, the two violins oppose each other in counterpoint, reducing the orchestra to a non-intrusive supporting element. At others, the two voices combine, and the relationship resembles that of the solo concerto, but with the power of two violins creating a more elaborate line than a single instrument could.

The piece opens with a four-part fugue, establishing the extensive counterpoint that permeates this first movement. The beginning of the first episode introduces the two solo violins. They take turns carrying the melody and counter-melody, as though engaging in a conversation, with each continually rebutting the other’s arguments. While the counter-melody quietly supports the more prominent melody, it also has a trajectory of its own. By the middle of the movement, it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish counter-voice from melody, as both players approach their complex, moving lines with equal intensity. Following a final iteration of the theme played by the entire orchestra, the movement ends with the recognition of both violins as evenly matched participants in this sonic back-and-forth.

Transitioning into the second movement, the orchestra falls into the background, exposing again the soloistic quality of the violins. Written in 12/8 time, this largo movement has a dance-like quality noticeable in the way the two voices are paired. Unlike in the first movement, the relationship of the two violins in the second is one of leading and supporting. As though dancing, the players take turns stepping forward, caringly supported by their partner as they reach higher and higher in their arpeggios. Even in the most soloistic moment, the other violin is not far behind, ready to recover the melody when the first player has had her fill.

Especially in contrast to the second movement, the third could be described as a frantic race between the two violinists to come out ahead by the end of the piece. Some of the most exciting canonic moments happen in this movement, with one violin repeating a phrase only a beat or two behind its partner. Not only is the tempo faster, but the counterpoint in this movement is more oppositional than in the first or second. While one voice plays a spirited, fast-paced rhythm, the other performs a more lyrical, legato phrase. The third movement is composed as a ritornello, with the orchestra playing a more active role than in the previous movement, intervening intermittently to break up the tussle between the soloists. By the end of the movement, the conversation has changed from two to three participants. The ensemble gets the last word, linking everything the two soloists have just said back to the movement’s opening theme.

Bach’s double violin concerto presents a considerable challenge to the violinists. Although written for two players, the Bach Double is not a duet in the typical sense. Instead, it requires the players to excel simultaneously as both soloist and accompanist, while also cooperating with the greater support of the orchestra. For Koh and Laredo, the relationship is even more unique. Formality may designate Laredo as mentor and Koh as student, but in taking on this masterpiece, hierarchy falls by the wayside. Indeed, it must do so in order for the collaborative quality of the concerto to be realized fully. Both have their moments of virtuosic solo performance, but equally virtuosic is their ability to respond to each other’s idiosyncrasies.

In listening to the rest of this album, consider how the experience of performing the Bach Double facilitates the rich partnership held between the violins in each of the subsequent works; and consider how, nearly 300 years after its composition, the Bach Double continues to influence contemporary artists. Among the works encompassed by the Two x Four project, the Bach is perhaps the most important. It represents not only a critical moment in music history, but also marks a pivotal juncture in the lives of the two devoted violinists. Approaching this work with mastery and care, Koh and Laredo bring Bach’s double violin concerto to life, and demonstrate the centrality of this work to their overall collaboration.

Philip Glass — Echorus

Consistently recognized as one of the most prolific and influential composers of the late-20th century, Philip Glass (b. 1937) has achieved a level of acclaim that few composers reach during their lifetimes. His compositions range from solo works to operas and everything in between. He has composed for dance companies, for major motion pictures, and for his own group, the Philip Glass Ensemble. Although his collaborations have run the gamut of artistic genres, each has a stylistic quality that identifies the composition distinctly and unmistakably as the work of Glass.

While the term “minimalist” is frequently used to describe Glass’s compositional style, he prefers to describe it as “music with repetitive structure.” To call something “minimal” implies a certain simplicity or ascetic quality, and while the individual elements of Glass’s compositions (such as rhythmic patterns or harmonic shifts) may appear straightforward, taken as a whole, they are not. Instead, Glass’s works are sonorously encompassing, frequently polyrhythmic and polyphonic, surrounding the listener with patterns, motifs, and variations that defy explanation on a measure-by-measure basis. In his compositions for multiple players, the individual voices combine to create a complex system of layers in which one line or another can be momentarily exposed or hidden. With his repetitive structures, Glass introduces changes slowly, sometimes almost covertly. Only by experiencing his works in their entirety can one hear and understand the true breadth of their development.

This condensed analysis of Glass’s style applies to Echorus, a chamber work for two solo violins and string orchestra structured as a chaconne, a compositional form popular during the Baroque era consisting of many short variations or decorations of an initial harmonic progression. The rhythmic and harmonic patterns in Echorus fall into two main categories, one moving and one sustaining. The piece opens with a fluid, arpeggiated chord from the ensemble’s higher strings, supported by a sustained, harmonizing pitch in the lower voices. The two lines change in synchrony, exploring the dissonance or consonance that results from subtly altering one note in the established chord. With their entrance, the solo violins likewise take up this cause; and while their rhythmic pattern is only a two- to three-note phrase played in unison, they carefully undertake a study of their joint sound. While they test the limits of their harmonies, they can rely on the omnipresent pulse of the ensemble to bring them back to the point of departure.

The title Echorus comes from the word “echo,” but the simultaneous appearance of “chorus” in the title should also be noted. As in the Bach double violin concerto, the violinists must be attentive to their complex relationship. Although one violin tends to lead the other in pitch or volume, the two lines are not explicitly divided by melody and harmony. As they intertwine with both the ensemble and each other, the effect is instead, one of fluctuation. At times, the ensemble echoes the poignant voices of the violins as they attempt to fly away from the harmony in the chord progression. In other moments, the violins echo each other and, although they play in rhythmic unison, one stays behind in pitch while the other leaps ahead, creating a miniature chorus of voices between the two instruments.

Glass originally composed Echorus for famed violinist Yehudi Menuhin and his protégé, Edna Mitchell. Written during the winter of 1994–1995, the piece came towards the end of Menuhin’s career, when he and Mitchell commissioned 15 composers to create works featuring the violin, based on the theme of universal human compassion. While Mitchell and Menuhin’s relationship began as one of student and teacher, it quickly developed into a collegial collaboration between two exceptional artists.

It seems destined, then, that Koh and Laredo would take up this piece that celebrates a relationship akin to their own. The theme of compassion is evoked by the cooperation of the two violins, both in terms of their musical synchrony and the physical setting of two players in the featured role. Working in tandem to create a luscious, sensitive partnership between their sounds, the violinists must play not for themselves, but for each other. By the end of the work, the solo violins’ sounds are slowly enveloped by that of the strengthening ensemble. The soloists end their last phrases with a final show of mutuality, receding together as though to say this exploration was enough for today, but they are not yet ready to part ways. For Koh and Laredo, this ending is perhaps a hopeful metaphor, a reminder that infinite possibilities still await the next journey of their two violins.

Katherine Bergstrom is a writer interested primarily in music, dance, and the performing arts. Originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota, she is now based in New York City.

Prince of Clouds

Program note by Anna Clyne

I composed Prince of Clouds at the Hermitage Artist Retreat in Summer 2012.

When writing, I was contemplating the presence of musical lineage — a family-tree of sorts that passes from generation to generation. This transfer of knowledge and inspiration between generations is a beautiful gift. Composed specifically for Jennifer Koh and Jaime Laredo, her mentor at the Curtis Institute of Music, this thread was in the foreground of my imagination as a dialogue between soloists and ensemble. For a composer, working with such virtuosic, passionate, and unique musicians is another branch of this musical chain.

Prince of Clouds was co-commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, IRIS Orchestra, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and Curtis Institute of Music. It was premiered in November 2012 at the Performing Arts Center in Germantown, Tennessee, with conductor Michael Stern. Subsequent performances took place in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall with conductor Harry Bicket; Royce Hall, Los Angeles, with conductor Jeffrey Kahane; and at the Miller Theatre in New York City.

Seasons Lost

Program note by David Ludwig

Seasons Lost is the story of the time before our winters and summers ran together; the time before warm rain where there should be snow, and deadly storms where there should be cool autumn days. I remember from my childhood growing up on the East Coast the four seasons that were once distinct, but that are now lost. The reality of global climate change is important for me to respond to, and so I wrote Seasons Lost to add my voice to the discussion.

With each season comes its number, and that numerology is found in the instrumentation and colors of the four movements of the piece. Numbers weave through the fabric of the music, as well, from the gradual unraveling of melodies to the building blocks of the harmonies throughout. The music begins in winter, in distant unisons of cold days where the light is icy blue and the air stings when it hits bare skin. The second movement is a duet between violin soloists; an intertwining of themes and melodies like the growing greenery of spring. The third movement portrays the heat of summer in trios of solo players set on a backdrop of hazy, smoky nights and smoldering bonfires. Quartets play in the last movement of fall to create the sonic image of howling winds in autumn that rustle the trees and shake their leaves to the ground.

Seasons Lost was commissioned by a consortium of the Delaware Symphony, Vermont Symphony, and Curtis Institute of Music after a project envisioned by soloists Jennifer Koh and Jaime Laredo, with generous additional support from Augusta Gross and Leslie Samuels.

Album Details

Total Time: 52:10

Producer: Judith Sherman

Engineer: George Blood

Editing: Bill Maylone

Recorded: March 12,15, and 17, 2013, in the Miriam and Robert Gould Rehearsal Hall at the Curtis Institute of Music

Front Cover Design: Luis Ibarra

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

Photography: Jürgen Frank

Publishers: Echorus (Dunvagen Music Publishers, 1995); Prince of Clouds (Boosey & Hawkes, 2012); Seasons Lost (David Ludwig Music, 2012)

Funded in part by a grant from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc.

© 2014 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 146