| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

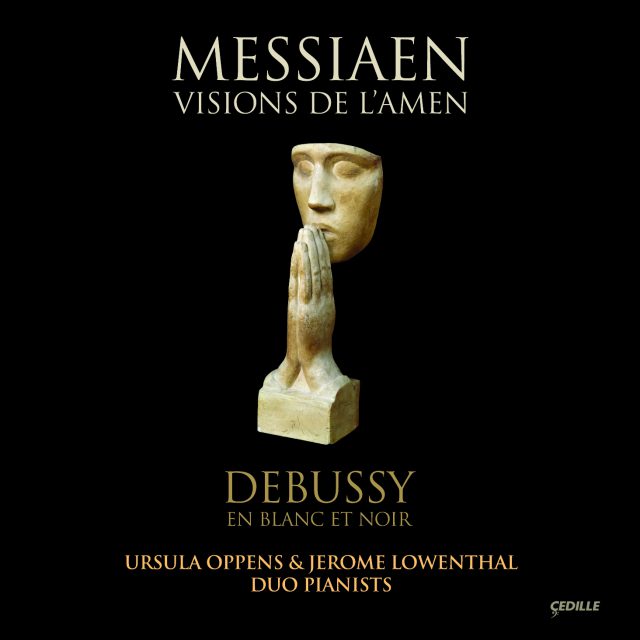

Two-Piano Music of Messiaen and Debussy

This is an inspired pairing 20th-century French works for duo piano composed during the century’s greatest conflicts: Olivier Messiaen’s Visions de l’Amen (Visions of Amen) and Claude Debussy’s En blanc et noir (In Black and White). On other recordings, Visions de l’Amen typically appears alone or as part of an all-Messiaen program.

Messiaen’s Visions de l’Amen, from 1943, was composed in wartime Paris during the German occupation. With an orchestral range of colors and immense dynamic range, it’s a monumental set of seven mystical meditations, often beginning subtly and building to an exhilarating intensity. From the first movement, “Amen of Creation” to the last, “Amen of Consummation,” the work is Messiaen’s musical metaphor of Life. Sonically powerful and emotionally demanding, it was composed with his unique imagination for sonority. Author and critic Paul Griffiths, in program notes for Carnegie Hall, wrote, “The two pianos together become a percussion orchestra, akin to the gamelans of Indonesia.”

Debussy’s En blanc et noir, from 1915, is the composer’s response to World War I. A landmark in the two-piano genre, the three-movement work is notoriously difficult to play. In the first movement, a vigorous waltz of clashing harmonies represents the “dance” of war, which is interrupted by military-sounding motifs. French and German musical themes battle for dominance in the second movement. The finale opens with a gentle D-minor theme reminiscent of Debussy’s Cello Sonata but becomes, in turns, sad and sinister, ending with a bitter dissonance that seems to suggest that the post-war years will be shadowed by memory.

Preview Excerpts

OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908 - 1992)

Visions de L’Amen

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 - 1918)

En blanc et noir

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletTwo-Piano Music of Messiaen and Debussy

Notes by Jerome Lowenthal

On December 27, 1915, a grand old man of French music wrote to his distinguished former student:

I advise you to look at the pieces for 2 pianos, Noir et Blanc [Black and White] which M. Debussy has just published. It is UNBELIEVABLE, and we must at all cost bar the gate of the Institute against a gentleman capable of such atrocities; they should be put next to the cubist paintings.

The writer was the great Camille Saint-Saëns and the recipient, Gabriel Fauré. It would be easy to attribute Saint-Saëns’s hostility to his crotchety conservatism and to a history of barbed relations with his younger colleagues. In addressing an attack of such virulence to Fauré, he may have assumed that the younger composer, although quite appreciative of Debussy’s music, would have enjoyed such a judgement of the music of his brilliantly successful rival. (In fact, Fauré and Debussy, always cool towards one another, had been somewhat drawn together by Debussy’s marriage to Fauré’s former mistress.)

It might also be thought that Saint-Saëns, whose aesthetic was formed by the principles of German music, would be outraged by the intense Germanophobia Debussy expresses in this work.

But in fact, Saint-Saëns, one of the most cultivated musicians of Europe, had only the year before expressed considerable, if qualified, admiration for Debussy’s talent and originality. As for politics, Saint-Saëns yielded to no one in his hysterical chauvinism, demanding that all German music be banned for the duration of the war.

It seems, then, to be the particular musical expression of En Blanc et Noir that called forth such condemnation. The association Saint-Saëns makes between this work and cubist paintings is particularly interesting. Debussy gives us no help in establishing a connection: the painter who inspired the original title, Caprices en blanc et noir, was Goya; and when the composer decided to lighten the color of the second movement, it was in favor of Velasquez. Nor did “les fauves” (the “wild beasts” of French art) inspire in him any sympathy: about Matisse, Vlaminck, and Derain he writes: “[they are] people who, I hope without malice, work hard to disgust others as well as themselves of painting.”

Nevertheless, there is, in these pieces, a novelty of juxtaposition and displacement that we, like Saint-Saëns, may perceive as cognate with the canvasses of Picasso and Braque.

Each movement is preceded by an epigraph that evokes French cultural tradition. Debussy did not particularly admire the music of Gounod, but did consider him an important French composer. It was in the libretto of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette that Debussy found a quatrain for the epigraph to the first movement of En Blanc et Noir: the old Capulet exhorting the youngsters at his ball to dance, while apologizing for being too old himself. In free translation:

He who does not dance

But remains in his place

In a low voice confesses

A secret disgrace

For Debussy the dance is a metaphor for the war and the disgrace is his inability to fight due to age and, for him, shameful illness.

In the music, the “dance” of war is represented by a vigorous waltz of clashing harmonies, with the two pianists, like battlefield antagonists, playing broken chords in contrary motion. A variety of military-sounding figures repeatedly interrupt the flow of the waltz. Fanfares insinuate themselves into the texture. Eventually, the two pianists agree and conclude the movement with a triple forte chord in C Major.

The second movment is dedicated to Lieutenant Jacques Charlot, “killed by the enemy the third of March,” 1915. In the score, it is preceded by an excerpt from Francois Villon’s “Ballade contre les ennemis de France” (Ballade Against the Enemies of France). With intense poetic imagery, the 15th century writer (three of whose ballades Debussy set for voice and piano) condemns to damnation “Qui mal vouldroit au royaume to France” (those who would wish ill to the kingdom of France). The music pits the Germans, represented by Luther’s chorale Ein Feste Burg (which Debussy had used years before to characterize the Protestantism of writer André Gide) against what the composer calls a “pre-Marsellaise carillon” repre-senting the French. Battle sounds are suggested by dissonant drum-like bass intervals. The battle is fierce, but the French are clearly the winners. The composer, writing to a friend about his music, his cancer treatments, and the war, concludes:

Death continues to exact its blind tribute. When then will hate end? And indeed is it hate that we should speak of in this story? When will we stop confiding the destiny of the nations to people who consider humanity as a means of achieving power?

The epigraph for the third movement, dedicated to “my friend, Igor Stravinsky,” comes from a poem by Charles d’Orleans, another 15th century poet the composer admired. The words “Yver, vous n’êtes qu’un villain” (Winter, you’re nothing but a boogie-man) are mirrored in a gentle D minor theme, reminscent of Debussy’s cello sonata. But the other thematic material is alternately sad and sinister, with occasional suggestions of military drums and fanfares. The final chord is quiet but bitter in its dissonance. The message seems to be that the war will end and spring will come again, but all will be shadowed by memory.

Like Debussy’s En Blanc et Noir, Messiaen’s 1943 Visions de l’Amen was composed in wartime Paris. For Debussy, the war meant unending loss, grief, and horror, which he expressed in his music and his letters. Messiaen tells us nothing of what the war meant to him, although the streets were filled with German officers and he gained his position at the Conservatoire because all the Jewish professors had been dismissed.

At the time of composition, Debussy was undergoing surgery and radium treatments that left him exhausted with pain. Messiaen had returned from eight months in a German prison camp to find his beloved wife showing the first signs of what would become total dementia. Debussy, in the epigraph to the first movement of En Blanc et Noir, alludes to his physical humiliation. As with his prison composition Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps, Messiaen alludes only to God and birds.

One need not question the composer’s literalness about both ornithology and theology to say there is a constant play of metaphor in his music, so that the “Abyss of the Birds” in the Quatuor can easily be understood as the despair of the prisoner, while the “Agony of Jesus” in the Visions may well be heard as an expression of the composer’s personal agony.

The work was commissioned by Concerts de la Pleiade, an organization created to circumvent German cultural restrictions. It was first performed publicly on May 10, 1943, but the day before, Messiaen and his brilliant teen-aged student Yvonne Loriod performed it in a private salon before an audience that included composers Honneger, Poulenc, and Jolivet. The music aroused immediate enthusiasm in some and annoyance in others — just as it has in the decades since. This is music of willed excess within closely calculated proportions, and of unbearable sweetness frequently overlaid with extreme harshness. Sonically powerful and emotionally demanding, it was composed with Messiaen’s unique imagination for sonority.

The first movement is titled “Amen of Creation.” The “amen” terminology comes from the book, Paroles de Dieu (God’s Words) by Ernest Hello, a theologian the composer much admired. The category of “amen” functions analogously to the “Regards” in Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jésus.

The music is a perpetual crescendo, recalling Ravel’s Bolero, but simpler and more exalted. In the key of A Major (that of several exalted or sensual works in the French canon: Debussy’s L’Isle Joyeuse, Franck’s Violin Sonata, and the finale of Ravel’s Piano Trio among others) the theme of “Creation,” square in phrasing and exotically diatonic in harmony (the exoticism created in part by Messiaen’s enharmonic notation), is played with slight variations five times, progressing from barely audible to triple forte. Meanwhile, in a treble register and in complicatedly irregular rhythms, all the sounds of the universe are evoked. In 39 measures, God’s command “Let there be light” has brought the world from tohu-bohu (formless chaos) into radiance. Throughout the movement, as in the entire work, the second piano, originally played by the composer, has the tunes, while the first piano, played by his student, muse, and future wife, has the clatter and clutter of creation.

In the second movement, called “Amen of the stars and of the ringed planet,” overlapping rhythmic and pitch patterns leap across all registers of the two pianos with ever-increasing complexity. To quote the composer: it is a “brutal and savage dance whose mixed movements evoke the life of the planets and the astonishing rainbow colors of the turning ring of Saturn.” The religious source for this movement is the deuterocanonical book of the bible, Baruch.

The third movement, “Amen of the agony of Jesus,” is a bipartite composition with coda (Messiaen’s underlying structures are often quite conventional). Each half contains three sections that could be described, respectively, as bitter, sweet, and agonized, with the agonized section greatly enlarged in sonority when it reappears. Programtically, this movement represents Jesus alone in the garden of olive trees. In the coda, the theme of Creation reappears while “a great silence, cut by several pulsations, evokes the unspeakable suffering of that hour.”

Movement No. 4: “Amen of Desire.” The composer: “Two themes of desire. The first, slow, ecstatic . . . the calm perfume of paradise. The second, extremely impassioned; in it the soul is pulled by a terrible love expressed in fleshly terms (see The Song of Songs); but there is nothing here that is carnal, only a paroxysm of thirst for Love.” This marvelous movement is structurally similar to the previous one: two-section bipartite, with a savage dance underlying the recapitulation and a peaceful coda.

The fifth movement is the “Amen of angels, saints, and birdsong.” We are back in A Major with the theme of Creation, which is presented with ravishing and constantly increasing ornamentation. This is the most pianistically sumptous of the seven movements, evoking little if any conventional spirituality. It is somewhat reminiscent of the penultimate movement of the Quartet for the End of Time.

Movement No. 6: “Amen of Judgement.” Cursed souls are fixed in their accursed state. This tripartite movement is powerful but short. Is it fair to infer that the composer’s heart was not really into damnation?

Movement No. 7: “Amen of Consummation.” “An incessant carillon of brilliant scintillant chords and rhythms . . . precious stones of the Apocalypse that ring, collide, dance, color and perfume the light of Life.” We are in A major once more, and the theme of Creation — stated, restated, varied, and revaried — resounds through the universe. This time the dynamic level begins at fortissimo, occasionally dropping down to a penetrating piano, but the total effect is overwhelming. The second piano has little to do but pound out the theme, while the first piano must perform unprecedented feats of virtuosity. Thus ends Olivier Messiaen’s musical metaphor of Life.

Album Details

Total Time: 60:51

Produced and engineered by Judith Sherman

Engineering and editing assistant: Jeanne Velonis

Piano technician: Christian Briggs

Steinway pianos

Schoeps microphones used on this recording: CMC-5 and CMC-6

Recorded June 3, 4, and 7, 2009, at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City

© 2010 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 119