| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

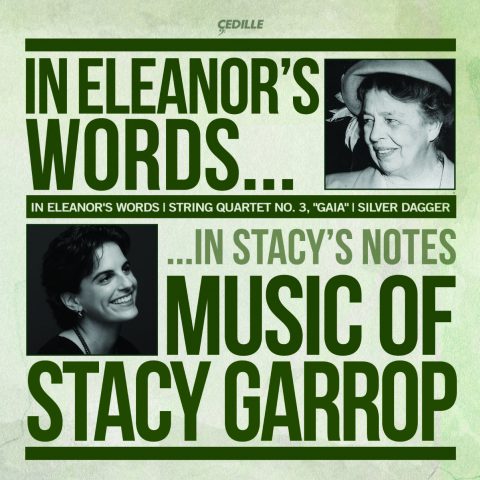

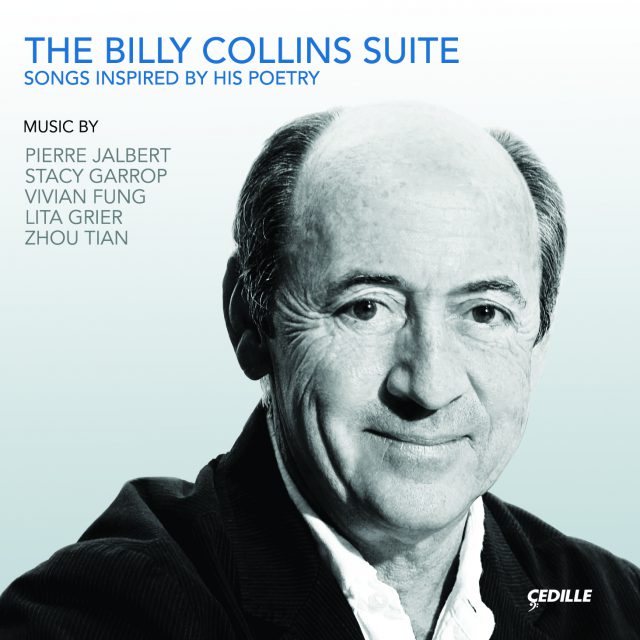

The Billy Collins Suite: Songs Inspired by his Poetry

Buffy Baggott, Lincoln Trio, John Bruce Yeh

Susan Cook, Yoko Yamada-Selvaggio, David Cunliffe, Marta Aznavoorian, Jonathan Beyer, John Goodwin, Tim Munro, Joel Link, Nuiko Wadden, Lita Grier, Stacy Garrop, Steve Robinson, Desirée Ruhstrat, Vivian Fung

Billy Collins, former U.S. poet laureate, has been hailed as the first American poet since Robert Frost to garner great critical acclaim and broad popular appeal in equal measure. “His poems generate surprise, inviting the reader to anticipate each new one as if it might be the best one yet” (World Literature Today). In Collins’s poetry, “even the most commonplace things never turn out quite the way you think they will” (Newsweek).

The Billy Collins Suite comprises intimate chamber settings for eleven Collins poems, some sung, others narrated. The CD includes Pierre Jalbert’s jazzy, other-worldly take on “The Invention of the Saxophone”; Stacy Garrop’s Ars Poetica, a four-song cycle ranging from a jaunty “Sonnet” to the heartbreaking “Endangered”; Vivian Fung’s Collins trilogy of vivid miniature comedy-dramas marked by especially effective use of the clarinet; Lita Grier’s poignant “Forgetfulness” and nostalgic “Dancing Towards Bethlehem”; and Zhou Tian’s “Reading an Anthology of Chinese Poems . . .” in which flute, viola, and harp evoke Far Eastern imagery.

Artists include Chicago Lyric and San Francisco Opera mezzo-soprano Buffy Baggott, rising young baritone Jonathan Beyer, Chicago Symphony Orchestra Acting Principal Clarinet John Bruce Yeh, flutist Tim Munro of eighth blackbird, saxophonist Susan Cook, the Lincoln Trio, harpist Nuiko Wadden, pianists Yoko Yamada-Selvaggio and John Goodwin, and narrator Steve Robinson of WFMT Radio.

The project was conceived and commissioned by Chicago’s innovative Music in the Loft chamber series, “one of the most unique springboards for young instrumentalists, singers and composers in the nation” (Chicago Tribune).

Preview Excerpts

PIERRE JALBERT

STACY GARROP

Ars Poetica

VIVIAN FUNG

LITA GRIER

ZHOU TIAN

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Billy Collins Suite

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

As it emerged in the Baroque period of the 17th and early 18th centuries, a suite was a set of instrumental pieces based on dance rhythms, all in the same key — creating a sense of unity — but varying widely in rhythm, tempo, and mood, providing marked contrasts from one movement to another. Among the best-known Baroque suites are the four Bach composed for chamber orchestra and those drawn from Handel’s Water Music.

This suite, paying tribute to an American poet whose works have garnered critical acclaim and popular success, differs in two obvious ways from its predecessors. First, it incorporates the human voice; we’ll hear a narrator, a mezzo-soprano, and a baritone. Second, the “movements” of the suite are by five different composers. Each of the compositions, moreover, could easily be performed on its own. Put together into a suite, however, they reveal profoundly different responses to provocative poetry, and invite us to reflect on how we respond to the poems and their varied musical interpretations.

The element of unity is provided by Collins’s poetry; contrast is supplied by the composers’ diverse styles and the way each “sets” the verses. The first, third, and fifth compositions involve a narrator, whose voice is sometimes isolated from, and sometimes combined with, the musical lines. The second and fourth pieces are more traditionally structured as songs. In the narrated pieces, Collins’s penchant for satire and comic one-liners is emphasized a bit more. In the songs, we experience perhaps more clearly not only the poet’s wryness but also the strength of his feelings. As for key signatures, or tonal centers: these are less important in 21st-century music than they were to Bach and Handel, but many of our pieces, inspired by the nature of their verses, do relate to traditional tonality.

In a New York Times article, Cynthia Magriel Wetzler wrote, “Luring his readers into the poem with humor, Mr. Collins leads them unwittingly into deeper, more serious places, a kind of journey from the familiar or quirky to unexpected territory, sometimes tender, often profound.” Mr. Collins himself has said, “Poetry is my cheap means of transportation. By the end of the poem the reader should be in a different place from where he started. I would like him to be slightly disoriented at the end, like I drove him outside of town at night and dropped him off in a cornfield.” He doesn’t like discussing his work, except for “its capacity to withstand discussion.” But the poetry here doesn’t have to withstand discussion: it’s being reflected and commented upon by the music.

The entire project is the brainchild of Chicago’s Music in the Loft chamber series and its founder, Fredda Hyman. It was underwritten by a board member, Dr. Peter Austin, who provided the funding to commission all five works that comprise the suite. Most of the series was performed at Music in the Loft’s Ninth annual Kleiner Benefit Concert in 2008, just prior to the recording sessions for this CD.

Opening the program, Pierre Jalbert’s “The Invention of the Saxophone” starts with no music at all: the narrator recites the first eight lines of the poem as a spoken solo, noting the achievement of Adolphe Sax, with an offhand reference to the medieval Danish historian, Saxo Grammaticus. Then, tentatively, out of dark silence, the first saxophone tones emerge, as though the world’s first saxophonist is just beginning to explore the possibilities of his new instrument. In the saxophone’s second measure, however, Jalbert establishes a three-note down-and-up motive, played in triplet rhythm, that will become a major thematic element of the piece.

This initial solo becomes a duo when the piano introduces its first theme, a rippling passage with chromatic intervals that also sound slightly tentative: how am I going to partner this new sonority? Now, for the first of several times, the pianist joins the narrator, repeating the keyboard passage until the lines of poetry are finished. In the piano we begin to discern rising three-note motives with dissonant clashes between right and left hands. The saxophone returns with a more sustained theme. It becomes a real melody for the first time. After the third stanza, the saxophone becomes more virtuosic, more assertive, more alive to the potential at her fingertips. The down-and-up triplet figure is heard again and again — sometimes very stretched out — as the piano continues its agitated patterns. Both instruments build to a powerful, insistent climax; then the texture abruptly shifts from legato to staccato, and the piano part turns from runs to chords. The saxophone now has, in essence, an accompanied cadenza, showing off what she’s discovered about the instrument. The piano continues frenetic runs and chords, using the keyboard’s highest and lowest registers. A long fortissimo section is highlighted by furiously repeated saxophone patterns derived from the three-note motive. Then a ritard, a softening, and sustained piano notes anchor the fourth stanza. The commentary from the saxophone seems to return us to the beginning, but this time the saxophone part is varied and elaborated: a lot has been learned. The piano’s accompaniment to the final stanza is subdued. Taking his cue from Collins’s verse, Jalbert “let[s] the music do the ascending.” And so it does, with the saxophone’s final statement ending high and faraway.

Collins’s “The Invention of the Saxophone” is a somewhat whimsical reflection on an instrument with a characteristic timbre, mixed with nocturnal imagery and references to the Second Coming. The verses gathered into Stacy Garrop’s group of four songs published under the title Ars Poetica are distinctly more personal. We’ll hear two reflections — one painful, one humorous — on the nature of poetry itself; then a rueful love note; and finally a meditation on the fate of the earth. Garrop’s music elaborates and illuminates these statements. Its effectiveness comes from sharp contrasts between lyricism and drama, from special sound effects on the three instruments, and from the demands made on the flexibility and expressiveness of the voice. The singer must be at various times teacher, commentator, and victim in a quartet consisting almost equally of beauty and heartache.

“Introduction to Poetry” begins in melodic sweetness that leads to chaos. Led in by the instruments, the voice part becomes increasingly excited, overjoyed by the exuberant freedom of poetry. Garrop’s tempo marking at the line “waving at the author’s name on the shore” is “Extremely energized.” But the triumphant instrumental interlude that follows turns suddenly threatening: the academic types arrive. Piano octaves and buzzing string trills, later tremolos, usher the voice back in, her part marked “throaty, snarling.” Now her line features tritones — intervals of an augmented fourth whose presence creates agitation and unrest — leading to a scream on high A. In the song’s coda the singer reiterates the poem’s opening line, “I ask them to take a poem,” with the same vocal motives as at the beginning, but with the joy all gone.

To deal with an older form of poetry, the sonnet, Garrop chooses a more “retro” music style: diatonic, even jaunty. The musical texture becomes more complex as Collins ponders the requirements of “get[ting] Elizabethan.” Then at the “turn” — the sonnet’s last six lines — we have faster-paced musical lines and more chromatic intervals until the bright C Major of the opening is restored on the final line, “come at last to bed.”

In “Vade Mecum” (Come with Me) an eerie opening atmosphere is induced via string harmonics: an effect produced by placing finger on string lightly, without pressing down onto the fingerboard, and drawing the bow lightly over the string. The sound is high-pitched, ethereal, and distant. Under these tones we hear emphatic repeated piano figures, while the singer’s detached notes enable us to envision the scissors, also represented by the strings, now playing staccato. The vocal part becomes more frenzied until the singer, at the end, gently accepts the idea of being part of “the book you always carry.” The instrumental postlude is once again frenzied, its repeated notes suggesting the idea of being pasted down.

“Endangered”: Muted violin and cello are heard over a portentous piano sound produced by striking the strings directly inside the instrument. These ominous sonorities introduce a singing voice that is at first almost monotone. The strings continue without vibrato while the pianist plays normally with a triple-meter “Minuet for the extinct animals.” A tonal center of G Minor gradually emerges; the strings’ mutes are removed but the dynamic remains soft. Major and minor modes are conflated as the animals move in and out of our view. The subdued ending poignantly evokes the emptiness of a barren earth.

Vivian Fung’s Collins trilogy uses explicit tone painting to create miniature comedy-dramas. The distinctive timbre of the clarinet is featured to make points and create moods. Unlike Garrop’s pieces, which echo the traditional genre of the song-cycle, Fung’s work is a three-act playlet in sound, akin to the words-and-music genre pioneered by Stravinsky in L’Histoire du Soldat. Narrator and instruments are closely integrated in “Insomnia” — not an obvious topic for humor, but Collins brings inevitable smiles with his image of the frenetic tricycle-rider. Repeated tremolo-like figures for the instruments represent the agitation and futility of the sleepless speaker; the soft dynamic is a touch of irony, since the insomniac’s brain is shouting. A short clarinet passage of quarter notes and staccato eighth notes evokes pacing the floor. With dramatic glissandos, clarinet and cello suddenly scream frustration. Then low piano octaves support the narrator again, while its chords underpin a virtuosic clarinet-cello dialogue. Fung suddenly changes gears, with very soft lightly-sketched patterns — the cellist playing in an unusually high register — as the speaker begins to hope he will at last find rest. And indeed, cello harmonics, a sustained clarinet tone, and a high keyboard postscript appear to bring repose.

As with Garrop’s “Endangered”, in “The Man in the Moon” the pianist is first asked to strum the strings inside the instrument. Random-sounding notes for clarinet and cello combine with the odd piano timbre to set the stage for fright. This fear soon turns to acceptance and appreciation of the moon-face, as the poet’s ruminations on a sky-personality are represented by wandering up-and-down melodic patterns presented in close imitation (the pianist now playing normally). Sustained notes for clarinet and cello are contrasted with agitated, rhythmically complex keyboard figurations until we see the fully-risen moon and reach a musical climax just before the words “he looks like a young man who has fallen in love with the dark earth.” Over ongoing piano patterns, under the narrator’s voice, clarinet and cello again enter a kind of dialogue: a theme of augmented intervals played almost canonically. After the poem’s final words, “He has just broken into song,” we hear that triumphant song, launched by these two instruments in unison, then slowly fading away as the pianist returns to strumming.

“The Willies” is all about instrumental sound effects. Several times the cello is asked to play pizzicato, and both cello and clarinet have eerie glissando passages. The narrator’s words are often broken up into short phrases by the instrumental commentary. A frequent component of the piano part is octave playing in the bass register: ominous, like the willies themselves. As the piano part becomes more complex, and all three instruments play staccato, the narrator describes the willies in almost-gory detail. The instrumental sound continues to intensify as the satirical underpinning of the poet’s intention becomes increasingly apparent. But don’t dismiss the feeling altogether: strong dynamic contrasts and stop-and-start playing lead to a fortissimo conclusion of outright agitation: after all, “the willies are the willies.”

The poignant poems Lita Grier chose for her part of The Billy Collins Suite are both about loss. The partly-diatonic, partly-chromatic melodies for the voice in “Forgetfulness” serve to emphasize the confusion of the singer as he loses his grip on both events and knowledge. The voice is often set in dialogue with the clarinet, which echoes and elaborates upon the singer’s motives, moving in close imitation with him. Meanwhile, the piano part, initially serene, moves to passages of agitation, but eventually settles into a ruminative state enhanced by the alternation of duple and triple meters. The free rhythms in the voice part and the notes themselves, which don’t establish a tonal center, indicate the off-again on-again aspect of the singer’s memory; we hear a final resolution on an A major chord, but will we remember it?

In “Dancing Toward Bethlehem,” the words suggest a dance rhythm, and Grier chooses a pleasantly nostalgic waltz. Whereas in “Forgetfulness” the voice part was sometimes reminiscent of operatic recitative, here it is more conventionally song-like: to use the opera analogy, this is the aria following the recitative. The clarinet inserts commentary over the chordal piano part. The steady pace becomes more inconsistent starting with “Just as the floor of the nineteenth century gave way,” but the waltz rhythm is restored in the postlude, with the singer humming his melody in partnership with the clarinet while the pianist contributes a steady pace. The song concludes wistfully with a sweet little clarinet scale-cadenza.

Zhou Tian has noted the “sparse, imagistic words and dry sense of humor,” plus the “great sense of delicacy and tenderness,” in Collins’s “Reading an Anthology…” In choosing the combination of flute, viola, and harp to join the narrator, he echoes the instrumentation of Debussy’s famous Sonata with its distinctive sound-world and mood. The verses reveal an American poet, reared and grounded in Western literary traditions, reacting to the very different mindset of Chinese poetry. We hear the narrator first, with no instruments around him; a plaintive flute theme gives a reply, and is joined softly by the harp and viola. The narrator’s next entrances are precisely indicated over the corresponding instrumental passages. The flute’s melodies, often pentatonic to evoke the Oriental imagery, are underpinned by faster-paced passages for the viola and rippling arpeggios for the harp. Flute and viola tremolos occasionally interrupt their other patterns. After the narrator describes one long Chinese poem title as “A beaded curtain brushing over my shoulders,” there comes an extended instrumental passage where the texture changes: the harp part becomes more agitated and extends over a wider range, the flute and viola play staccato, and the tempo picks up. Then a richly melodic viola solo, a tiny cadenza for the flute, a viola passage played with the wood of the bow, and a tempo shift to adagio introduce the stanza beginning “Ten Day of Spring Rain…” spoken over a more serene instrumental trio. The aim of poet and composer becomes clear in the final lines: to illuminate the idea of listening. The poem’s final word, “listen,” is emphasized by sustained flute tones, a soft viola tremolo, and the harp in its low register. The flute theme from the beginning is restated over a quiet, freely-paced tremolando passage for the harp and a viola texture alternating between tremolos and doubled notes. We have achieved understanding through listening.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 54:45

Production Credits

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: May 5 and 6, July 7, and September 17, 2008 in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago Chicago

Steinway Piano

Steinway Piano Technician: Charles Terr

Art Direction: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

Front Cover: Photo of Billy Collins by Steven Kovich – www.kovich.com

© 2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

Publishers:

“The Invention of the Saxophone” ©2003 Pierre Jalbert

Ars Poetica ©2007 Stacy Garrop

“Insomnia”, “The Man in the Moon”, and “The Willies” ©2007 Vivian Fung

“Forgetfulness” and “Dancing Towards Bethlehem” ©2008 Lita Grier

“Reading an Anthology of Chinese Poems of the Sung Dynasty, I Pause to Admire the

Length and Clarity of Their Titles” ©2008 Zhou Tian

CDR 90000 115