| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

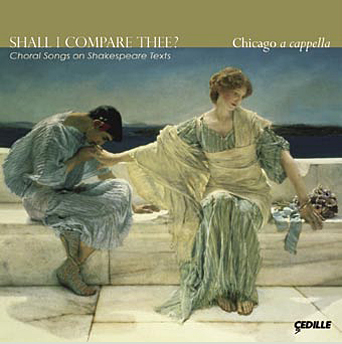

Shall I Compare Thee?

On its new CD, the “world class” (Fanfare) nine-voice ensemble Chicago a cappella brings its trademark “wit, imagination, [and] flawless intonation” (Chicago Tribune) to 23 contemporary choral settings of Shakespeare texts – including ten recorded premieres and three works composed expressly for the group.

Making its Cedille Records debut, Chicago a cappella performs artful arrangements that draw from influences ranging from bossa nova and the blues to Renaissance and medieval modes. You’ll hear a fascinating spectrum of styles within single works and across the entire program. This is one CD where (in the words of the Bard) “music and sweet poetry agree.”

Preview Excerpts

KEVIN OLSON (b. 1970)

MARTHA SULLIVAN (b. 1964)

JAAKKO MÄNTYJÄRVI (b. 1963)

Four Shakespeare Songs

MATTHEW HARRIS (b. 1956)

JOHN RUTTER (b. 1945)

NILS LINDBERG (b. 1933)

HÅKAN PARKMAN (1955–1988)

GYÖRGY ORBÁN (b. 1947)

JUHANI KOMULAINEN (b. 1953)

Four Ballads of Shakespeare

ROBERT APPLEBAUM (b. 1941)

Artists

7: from Shakespeare Songs

13: from Three Shakespeare Songs

Program Notes

Download Album BookletShall I compare thee?

Notes by Jonathan Miller

This recording had its genesis in June 2002, when Chicago a cappella held a competition. We put forth an international call for scores for our all-Shakespeare concerts, to be held in early 2003. The intention of the concert was to feature excellent new choral works based on texts by Shakespeare. We added the additional requirement that every piece be new to Chicago audiences — i.e., would be having its Chicago premiere. This condition meant that we would be looking in some unusual nooks and crannies of new music, intentionally taking a pass on many well-known works, such as Frank Martin’s Songs of Ariel or the Vaughan Williams a cappella cycle.

The songs by Kevin Olson and Martha Sullivan (tracks 1 and 2), as well as Robert Applebaum’s “Witches’ Blues” (track cm), were composed specifically for our competition. We were honored to receive works of such high quality, so newly created, along with the many dozens of other pieces that were submitted.

We performed a total of twenty-three short works on that program, seven of which were world premieres. Composers came from far and near to attend the performances during that cold February in 2003. Matthew Harris and Martha Sullivan flew in from New York City, while Jaakko Mäntyärvi came from Helsinki. They joined our local composer-stars in post-concert conversations with our audiences.

Many of the texts on this recording have been set to music elsewhere. In some cases, those compositions are now as iconic in the world of choral music as their texts are in the literary canon. Some texts have rarely, or never, been set to music before. Other lines did not necessarily carry deep dramatic weight in the plays themselves where they first appeared. Yet all have taken new wing in musical form, thanks to these composers. As the title of this disc suggests, we can compare these three settings of Sonnet 18 to one another, each of which draws out different qualities of the same poem; so long as men (and women) can breathe and ears can hear, composers will surely continue their creative work on these texts for centuries to come.

We have made a few substitutions from our live concerts for purposes of this recording. The Rutter song, for example, is a perennial favorite, which we performed on our debut concert in 1993. Nevertheless, the intent of this disc remains to showcase the music of composers of our time, who have so deftly and lovingly set to music the immortal words of Shakespeare.

Kevin Olson: Summer Sonnet (Sonnet 18)

Kevin Olson (b. 1970) is active as a pianist, composer, and teacher. A faculty member at Elmhurst College, near Chicago, he teaches classical and jazz piano and music theory, and serves as director of music admissions. His compositions have been commissioned and premiered by many groups, including the American Piano Quartet, the Rich Matteson Jazz Festival, and the Elmhurst College Chamber Singers.

This smooth, bossa-nova setting of Sonnet 18 has been described as “Shakespeare by way of Brazil.” Olson combines the ardor of love with refinement and restraint. The song mixes a bravura tenor solo with a classy, confident, Sergio Mendes-style vocal background.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

2 Martha Sullivan: Blow, blow, thou winter wind (As You Like It, II, vii)

Martha Sullivan (b. 1964) is an acclaimed composer of choral and vocal music whose prizes include grants from Meet the Composer and winning the Dale Warland Singers’ 2003 Choral Ventures™ commission competition. She is also a virtuoso New York-based soprano, flexible and comfortable with musical styles ranging from medieval to contemporary. She is a member of Toby Twining Music and regularly performs with leading new-music ensembles in the northeastern United States.

The text comes from the second act of As You Like It. The composer writes:

The singer in the play is Amiens, one of the courtiers of the exiled

Duke Senior. He is called upon to sing over the dinner that the

Duke shares with the likewise exiled Orlando when they first

meet in the forest of Arden. It may be read as a commentary

on Orlando’s and the Duke’s similar situations (both have been

exiled to the forest by their ambitious and jealous brothers), or

perhaps it is a bit of catharsis. Either way, I take the line “This life

is most jolly” as irony.

The overall feel of Sullivan’s setting could be called “modern quasi-modal.” She incorporates a wide combination of musical styles and influences, from the Italian 14th century to Jethro Tull. An exotic flavor creeps in at a few phrase endings, where Sullivan brings in the “Landini cadence,” a nod to the medieval Italian composer. The refrain is a driving, Celtic-sounding chorus; here the composer asks the singers to make the accents round and hearty, “like the swing of a pendulum (or a beer stein).”

Amiens:

Blow, blow, thou winter wind,

Thou art not so unkind

As man’s ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen

Because thou art not seen,

Although thy breath be rude.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the green holly:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly:

Then, heigh-ho! the holly!

This life is most jolly.

Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky,

Thou dost not bite so nigh

As benefits forgot:

Though thou the waters warp,

Thy sting is not so sharp

As friend remember’d not.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the green holly:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly:

Then, heigh-ho! the holly!

This life is most jolly.

3–6 Jaakko Mäntyjärvi: Four Shakespeare Songs

Finnish composer Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (b. 1963) is one of the leading writers of choral music of his generation. He calls himself an “eclectic traditionalist,” a label that certainly fits this cycle. He is harmonically adventurous but within a tonal language that choral singers can readily grasp. Mäntyjärvi works as a translator between Finnish and English, and his command of English is astounding.

Four Shakespeare Songs (1984) was dedicated to the Savolaisen Osakunnan Laulajat student choir. The composer was studying English at a university when he composed the cycle, which he describes as “varied and demanding.” The level of nuance and emotional expression in these pieces is remarkable, from wordpainting (such as “weep” in “Come Away, Death”) to overall delineation of feeling (as in the almost excruciatingly tender “Lullaby”).

Few choral pieces anywhere can match the ferocious enthusiasm of Mäntyjärvi’s “Double, double, toil and trouble.” The famous text from Macbeth meets music of like intensity. Indeed, the tempo is marked Allegro non troppo ma feroce. The song is cast in a relentlessly shifting and irregular meter, in which the witches’ manic brewing takes gleeful, macabre flight. Most often, Mäntyjärvi gives the narrative voices of all three witches to the entire chorus, magnifying the witches’ warped excitement.

The cycle concludes with the slow, atmospheric “Full fathom five.” From The Tempest, this is the song that the shipwrecked Prospero asks the “airy spirit,” Ariel, to sing. Prospero wants Ariel’s song to lure Ferdinand, son of Alonso, Duke of Naples, to the place where Prospero is waiting. Ferdinand believes his father has drowned, a fear that Ariel’s song vividly illustrates. Musical devices such as augmented triads lend a creepy, otherworldly flavor to the text, strengthening the word images of Alonso’s body being turned into treasures of coral and pearls.

3 Come Away, Death (Twelfth Night, II, iv)

Feste:

Come away, come away, death,

And in sad cypress let me be laid;

Fly away, fly away, breath;

I am slain by a fair cruel maid.

My shroud of white, stuck all with yew,

O prepare it;

My part of death no one so true

Did share it.

Not a flower, not a flower sweet,

On my black coffin let there be strewn:

Not a friend, not a friend greet

My poor corpse where my bones shall be thrown:

A thousand thousand sighs to save,

Lay me, O, where

Sad true lover never find my grave,

To weep there.

4 Lullaby (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, II, ii)

First Fairy:

You spotted snakes with double tongue,

Thorny hedgehogs, be not seen;

Newts and blind-worms, do no wrong,

Come not near our fairy queen.

Chorus:

Philomel, with melody

Sing in our sweet lullaby;

Lulla, lulla, lullaby,

lulla, lulla, lullaby:

Never harm,

Nor spell nor charm,

Come our lovely lady nigh;

So, good night, with lullaby.

First Fairy:

Weaving spiders, come not here;

Hence, you long-legg’d spinners, hence!

Beetles black, approach not near;

Worm nor snail, do no offence.

Chorus:

Philomel, with melody, etc.

5 Double, Double, Toil and Trouble (Macbeth, IV, i)

[SCENE I. A cavern. In the middle, a boiling cauldron. Thunder. Enter the three Witches]

First Witch

Thrice the brinded cat hath mew’d.

Second Witch

Thrice and once the hedge-pig whined.

Third Witch

Harpier cries ‘Tis time, ‘tis time.

First Witch

Round about the cauldron go;

In the poison’d entrails throw.

Toad, that under cold stone

Days and nights has thirty-one

Swelter’d venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i’ the charmed pot.

ALL

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

Second Witch

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the cauldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and owlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

ALL

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Third Witch

Scale of dragon, tooth of wolf,

Witches’ mummy, maw and gulf

Of the ravin’d salt-sea shark,

Root of hemlock digg’d i’ the dark,

Liver of blaspheming Jew,

Gall of goat, and slips of yew

Sliver’d in the moon’s eclipse,

Nose of Turk and Tartar’s lips,

Finger of birth-strangled babe

Ditch-deliver’d by a drab,

Make the gruel thick and slab:

Add thereto a tiger’s chaudron,

For the ingredients of our cauldron.

ALL

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Second Witch

Cool it with a baboon’s blood,

Then the charm is firm and good.

[HECATE speaks and sings to the other three Witches, then retires.]

Second Witch

By the pricking of my thumbs,

Something wicked this way comes.

Open, locks,

Whoever knocks!

6 Full Fathom Five (The Tempest, I, ii)

Ariel:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

[Spirits, within:] Ding-dong.

Ariel: Hark! now I hear them—

[Spirits, within:] Ding-dong, bell.

7-10 Matthew Harris: from Shakespeare Songs

With his Shakespeare Songs, now spanning five published collections, Matthew Harris (b. 1956) has carved out a distinctive niche in vocal ensemble music. Trained as a musicologist, he weaves older and modern musical styles together with impressive ease. Harris has been honored with composition prizes by the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and Tanglewood, among many others. These four Shakespeare songs are drawn from different published volumes. In each song, well aware of the styles in both Elizabethan and more recent settings of these famous words, Harris thoughtfully avoids musical cliché, claiming the texts refreshingly as his own.

“It Was a Lover and his Lass” is an easy, almost languid processional, evoking the image of a maiden and her consort moving gently through the heather on a spring day. For listeners familiar with the famous lute-song by Shakespeare’s contemporary, Thomas Morley, the contrast with Harris’s setting will be clear. The composer writes: “Instead of the lively romp found in other settings of this lyric, my ‘It was a Lover and His Lass’ is a slow, gentle idyll of young love in the spring.” The relevant scene in As You Like It finds Touchstone, the jester, betrothed to the goatherd woman, Audrey. Both ask two pages to sing in honor of their engagement. Whereas Touchstone finds the pages’ song “untunable,” Harris’s setting happily redeems their lyrics.

Harris chose to set “Take, O Take Those Lips Away” with “the fast, driving fury of a lover scorned” instead of the more typical slow lament (or Parkman’s more lighthearted setting on track bn). The boy who sings to Mariana to start Act IV of Measure for Measure does not seem particularly distressed; nevertheless, the musical result here is a well-balanced song of heartache. (In some modern productions, Mariana sings the words herself, expressing her own misery.)

“Who Is Silvia?” is the Host’s serenade in honor of Silvia, the object of amorous rivalry in The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Both Valentine and Proteus, the gentlemen in question, love Silvia. In the end, Valentine yields Silvia to Proteus as a gesture of his abiding friendship. Harris’s setting is something of a musical trick: he starts the song as a stately madrigal, but suddenly switches gears and channels the ardor of “all the swains” into the blues. The chorus accompanies the alto soloist with a back-beat figure reminiscent of early Motown. After a return to the pompous

madrigalian tone of the opening, the blues literally get the last word.

From Hamlet, “And Will A’ Not Come Again?” is Ophelia’s haunting lament for the death of Polonius, her father. She directs her final outburst at her brother Laertes, a wail fueled by her outrage at Polonius’s lack of a proper burial. In his setting, Harris makes skillful use of chained suspensions, a classic 16th-century device championed by Monteverdi. Harris also gently alternates between major and minor versions of the same chord at the very end for the words “God ’a’ mercy on his soul” — a subtle nod to Ophelia’s overwrought state.

7 It Was a Lover and his Lass (As You like It, V, iii)

Both Pages:

It was a lover and his lass,

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino,

That o’er the green corn-field did pass,

In spring time, the only pretty ring time,

When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding;

Sweet lovers love the spring.

Between the acres of the rye,

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino,

These pretty country folks would lie,

In spring time . . .

This carol they began that hour,

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino,

How that a life was but a flower

In spring time . . .

And therefore take the present time,

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino;

For love is crowned with the prime

In spring time . . .

8 Take, O Take Those Lips Away (Measure for Measure, IV, i)

Boy:

Take, O, take those lips away,

That so sweetly were forsworn;

And those eyes, the break of day,

Lights that do mislead the morn:

But my kisses bring again, bring again;

Seals of love, but sealed in vain, sealed in vain.

9 Who is Silvia? (Two Gentlemen of Verona, IV, iv)

Host:

Who is Silvia? what is she,

That all our swains commend her?

Holy, fair and wise is she;

The heaven such grace did lend her,

That she might admired be.

Is she kind as she is fair?

For beauty lives with kindness.

Love doth to her eyes repair,

To help him of his blindness,

And, being help’d, inhabits there.

Then to Silvia let us sing,

That Silvia is excelling;

She excels each mortal thing

Upon the dull earth dwelling:

To her let us garlands bring.

10 And Will A’ Not Come Again? (Hamlet, IV, v)

Ophelia:

And will a’ not come again?

And will a’ not come again?

No, no, he is dead:

Go to thy death-bed:

He never will come again.

His beard was as white as snow,

All flaxen was his poll:

He is gone, he is gone,

And we cast away moan:

God ’a’ mercy on his soul.

11 John Rutter: It Was a Lover and his Lass

John Rutter’s (b. 1945) compositional career has embraced large- and smallscale choral works, orchestral and instrumental pieces, a piano concerto, two children’s operas, music for television, and specialist writing for such groups as the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble and the King’s Singers. His larger choral works include Requiem, Gloria, and Magnificat (1990). These have been performed many times in Britain, the USA, and a growing number of other countries. From 1975 to 1979 he was Director of Music at Clare College, whose choir he directed in a number of broadcasts and recordings. After giving up the Clare post to allow more time for composition, he formed the Cambridge Singers as a professional chamber choir primarily dedicated to recording, and he now divides his time between composition and conducting. He has guest-conducted or lectured at many concert halls, universities, churches, music festivals, and conferences in Europe, Scandinavia, and North America. In 1980 he was made an honorary Fellow of Westminster Choir College, Princeton, and in 1988 a Fellow of the Guild of Church Musicians. In 2002 his setting of Psalm 150, commissioned for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, was performed at the Service of Thanksgiving in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Penned in 1975, this light, breezy, jazzy song in five voice parts gives the feeling of a summer wedding — after the vows are done and the happy couple skips down the aisle. In fact, Chicago a cappella sang this piece on just such an occasion in 1994.

Text: see track 7

12 Nils Lindberg: Shall I compare? (Sonnet 18)

Swedish jazz pianist and composer Nils Lindberg (b. 1933) has developed a unique crossover idiom by combining elements of folk music and jazz with the formal structures of classical music. His orchestral works include Lapponian Suite, Concerto Grosso in Dalecarlian Style and Dalecarlian Tales. The 1990s aroused an interest in choral music that resulted in his large-scale Requiem for mixed choir, soloists, and enlarged big band. A great success, it has been performed more than 50 times in Europe and the US since its premiere in 1993. In 2002, Lindberg completed a sequel: A Christmas Cantata, built on traditional English Christmas Carols. For several years he composed and arranged music for the Hanover Symphony Orchestra; he later wrote for Duke Ellington and his band.

Another major Lindberg composition is the suite O, Mistress Mine, a compilation of Elizabethan poems set for mixed choir a cappella. A part of that cycle, Shall I compare? was the best-selling choral piece in Sweden in 1998. Lindberg’s setting, in block chords throughout like a hymn, is emotionally straightforward — yet in characteristically Nordic manner, the emotion is always contained. The piece begins in the spare, open key of A minor and moves through several key areas, with dense minor-seventh chords predominating. The feeling is never fully expressed until the penultimate line, where Lindberg moves in full force to the bright, shimmering key of F-sharp major.

Text: see track 1

Håkan Parkman: from Three Shakespeare Songs

His career cut tragically short by an accident, Håkan Parkman (1955–1988) left a few gems for posterity and a great deal of unfulfilled promise. He directed several choirs in his native city of Uppsala, Sweden, plus the town’s theatre orchestra. He taught choral conducting and composed several works for soloist, choir, and instruments together. Among his larger compositions is his Lyrisk svit (Lyric Suite) for baritone solo, mixed choir, and orchestra. Among his few published works is the lovely cycle of Three Shakespeare Songs, from which these are the two a cappella movements. The Madrigal is a flirtatious, playful, almost glib setting of the Boy’s song in Measure for Measure. In almost complete contrast, Parkman’s Sonnet 147 is dark, brooding, and somber. Its soprano solo line moves in careful steps, up and down the scale, relentlessly charting the course of love’s feverish movement. After moving into a bright major key for lines 9 through 12, Parkman repeats the first eight lines yet again, underscoring the intensity of Shakespeare’s love-fever, only to turn jarringly at the end to the words “hell” and “night.”

13 Madrigal (Take, O Take Those Lips Away)

Text: see track 8

14 Sonnet 147 (My love is as a fever)

My love is as a fever, longing still

For that which longer nurseth the disease,

Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill,

The uncertain sickly appetite to please.

My reason, the physician to my love,

Angry that his prescriptions are not kept,

Hath left me, and I desperate now approve

Desire is death, which physic did except.

Past cure I am, now reason is past cure,

And frantic-mad with evermore unrest;

My thoughts and my discourse as madmen’s are,

At random from the truth vainly express’d;

For I have sworn thee fair and thought thee bright,

Who art as black as hell, as dark as night.

15 György Orbán: Orpheus with his lute (Henry VIII, III, i)

Born in 1947 in the Romanian province of Transylvania, Orbán emigrated to Hungary in 1979. He was recently appointed Associate Professor of composition at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music in Budapest.

Orbán’s music defies easy classification. He has a superb command of harmony, which he combines with a keen rhythmic sense and a gift for setting language for singers. He includes the occasional Eastern-European influence as well, creating a style with a strong personal stamp. His best-known work, Daemon Irrepit Callidus, has been a top-selling title, and his haunting Mass No. 6 for treble voices and piano is powerfully reminiscent of Debussy.

This text has been set by dozens of composers. Orbán’s version comes from the set Three Antique Pieces. Remarkably, the work was originally composed in Hungarian in the early 1990s, then translated into English. In the Shakespeare play, also known as All Is True, Queen Katherine of Aragon finds herself increasingly out of favor with

Henry VIII, asking for consolation from a gentlewoman’s lute-song. Unlike some of the British settings, which set the text in a more innocent vein, Orbán seems fully aware of Katherine’s complicated predicament, weaving a shifting set of harmonies in and out among the six-voice texture.

Gentlewoman:

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain tops that freeze,

Bow themselves when he did sing:

To his music plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Every thing that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads, and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or hearing, die.

16 György Orbán: O mistress mine! (Twelfth Night, II, iii)

This song from Twelfth Night is little more than a filler-ditty, sung by the brilliant, hilarious fool Feste to Sir Toby and Sir Andrew as comic relief in the action. A more typical setting of this text (such as Morley’s famous lute-song) stresses earnestness as the primary value. Orbán instead treats the text as a pop-song lyric, giving it a musical language almost as playful as a commercial jingle. He adds a roulade on the words “Diridon, diridon” to emphasize the sense that love is ephemeral, so the time to indulge in it is now.

Feste:

O mistress mine, where are you roaming?

O stay and hear, your true love’s coming

That can sing both high and low.

Trip no further, pretty sweeting;

Journeys end in lovers’ meeting,

Ev’ry wise man’s son doth know.

What is love? ‘Tis not hereafter;

Present mirth hath present laughter;

What’s to come is still unsure:

In delay there lies no plenty;

Then come kiss me, sweet and twenty;

Youth’s a stuff will not endure.

17-20 Juhani Komulainen: Four Ballads of Shakespeare

Juhani Komulainen (b. 1953) studied in Finland with Einojuhani Rautavaara and at the University of Miami in the USA. He rose to prominence quickly in the early 1990s, winning several composing competitions for choirs. His choral output varies widely in difficulty, as he tailors his writing to the level of the ensemble in question.

Komulainen wrote Four Ballads of Shakespeare for a Finnish amateur choir. He set himself the daunting task of taking on some of the most profound and memorable passages of prose in Shakespeare’s canon. Beginning with Hamlet’s immortal words, he brings us to Helena in the enchanted forest, then to Juliet in her bower, and finally to Macbeth’s despair upon learning of his wife’s suicide. Komulainen ends his setting of this last text before Macbeth’s final words: “It is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.”

The composer’s gift in this cycle lies partly in the way he moves the text around to different voice parts, putting “oo” or “ah” in others to give texture and harmonic color without distracting from the main message. The harmonies are clean, clear, and direct; the dynamics are only slightly jarring yet always well-placed. Perhaps the most stunning music in the cycle comes at the end of “O weary night,” Helena’s lament in A Midsummer Night’s Dream as she falls asleep in the forest. Komulainen ingeniously splits the women’s voices into four undulating, overlapping cascades on the word “sorrow,” while the men sing in open fifths to “Steal me a while from mine own company.” He then has the voices switch roles, where the word “sorrow” in the men is overlaid with a Mediterranean-sounding female melody. The ensemble ends in a unified declamation of “company” that, despite the word, feels unbearably lonely.

17 To be, or not to be (Hamlet, III, i)

Hamlet:

To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?

18 O weary night (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, III, ii)

Helena:

O weary night, O long and tedious night,

Abate thy hour! Shine comforts from the east,

That I may back to Athens by daylight,

From these that my poor company detest:

And sleep, that sometimes shuts up sorrow’s eye,

Steal me awhile from mine own company

19 Three words (Romeo and Juliet, II, ii)

Juliet:

Three words, dear Romeo, and good night indeed.

If that thy bent of love be honourable,

Thy purpose marriage, send me word to-morrow,

By one that I’ll procure to come to thee,

Where and what time thou wilt perform the rite;

And all my fortunes at thy foot I’ll lay

And follow thee my lord throughout the world.

20 Tomorrow and tomorrow (Macbeth, V, v)

Macbeth:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow; a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more.

21 Robert Applebaum: Spring (Love’s Labour’s Lost, V, ii)

A prolific composer of choral music in both English and Hebrew, Robert Applebaum (b. 1941) has had works premiered by the Coriolis Ensemble, Kol Zimrah, the Lakeshore Choral Festival, and at the North American Jewish Choral Festival. He recently retired from a career teaching chemistry and physics at New Trier High School on Chicago’s North Shore. He appears regularly as a jazz pianist in concert with his son Mark, recently completing a concert tour of Tunisia. In addition to a full schedule of composing choral music and performing, Applebaum also leads liturgical music and serves as Composer-In-Residence at JRC, the Jewish Reconstructionist synagogue in Evanston, Illinois.

At the very end of Love’s Labour’s Lost, the final entertainment of the play contrasts the songs of the cuckoo and the owl. The playful call of the cuckoo (set here in the women’s voices) warns the jealous husband that cuckoldry is near: “O word of fear / Unpleasing to a married ear.” Armado refers to the cuckoo’s song as “the songs of Apollo,” and the play ends there.

Spring:

When daisies pied and violets blue

And lady-smocks all silver-white

And cuckoo-buds of yellow hue

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men, for thus sings he,

Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo: O, word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear!

When shepherds pipe on oaten straws,

And merry larks are ploughmen’s clocks,

When turtles tread, and rooks and daws,

And maidens bleach their summer smocks,

The cuckoo then, on every tree,

Mocks married men, for thus sings he:

Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo: O, word of fear,

Unpleasing to a married ear!

22 Robert Applebaum: Witches’ Blues

Applebaum has a full command of jazz harmony, which gives his music an infectiously American stamp. These qualities are perhaps most evident in Witches’ Blues, which draws on the spirit of Gershwin to delightful effect.

Text: see track 5

23 Robert Applebaum: Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Applebaum’s wrenchingly sad, yet exquisitely beautiful music reflects the darker side of Sonnet 18. It was composed under tragic circumstances: the composer notes, “Sonnet 18 was written in memory of our daughter Carolyn. She was a drama teacher at Wilmette Junior High when she died suddenly of heart failure. She loved Shakespeare, and the sonnet was read at her funeral service. I decided to set it about a month after that.”

The music is gently tonal, adding skillful flats where most poignantly appropriate, rounding out a song of profound dignity. While many composers boldly breeze through the lines “Nor shall Death brag thou wanderst in his shade,” Applebaum instead reflects on loss, reminding us that “And every fair from fair sometime declines.” The score is dedicated to Carolyn: “This gives life to thee.”

Text: see track 1

Album Details

Total Time: 63:00

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Session Director: Patrick Sinozich

Recorded: November 13, 2004; and January 14-16 and March 19, 2005 at Northeastern Illinois University

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond & Pete Goldlust

Front cover: Ask me no more, 1906 (oil on canvas) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema © The Bridgeman Art Library

© 2005 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 085