| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

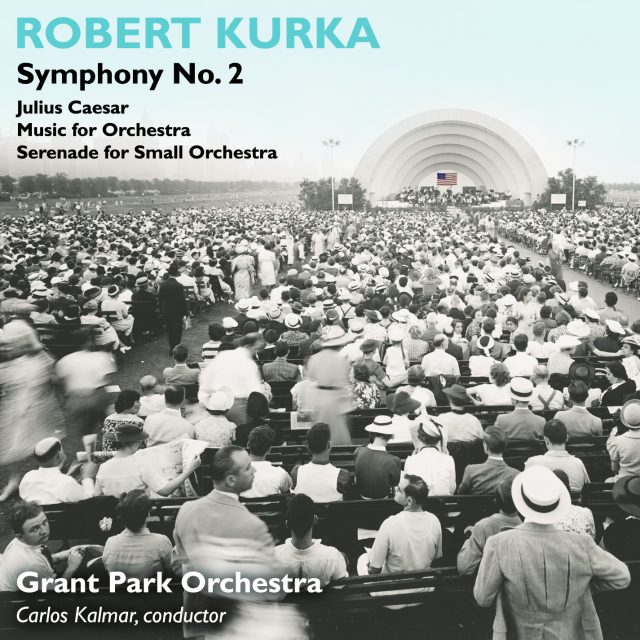

The first CD devoted exclusively to the robust orchestral music of twentieth-century American composer Robert Kurka (1921-1957) looks beyond the best-known works of this too brief career, The Good Soldier Schweik opera and orchestral suite, to illuminate a truly original talent.

The Chicago-area native, a rising musical star of the 1950s, whose teachers included Otto Leuning and Darius Milhaud, died of leukemia at the age of 35, while completing his opera.

Symphonic Worksby Robert Kurka, presents the world premiere recordings of Kurka’s Julius Caesar, Symphonic Epilogue after Shakespears, Op. 28, and Music for Orchestra, Op.11; the first CD recording of Serenade for Small.

Performed by Chicago’s Grant Park Orchestra under its principal conductor Carlos Kalmar, the works were recorded in late June 2002 and 2003 at summer-festival concerts in Orchestra Hall.

Preview Excerpts

ROBERT KURKA (1921-1957)

Symphony No. 2, Op. 24

Serenade for Small Orchestra, Op. 25

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletOrchestral Music by Robert Kurka (1921–1957)

Notes by Richard E. Rodda

Early death always chafes the heart, and with special poignancy at the loss of a gifted creative person. The misfortune that allowed so many composers, great and obscure, to die filled with unrealized music, also befell American composer Robert Kurka. Kurka, of Czech descent, was born in Cicero, Illinois (just outside Chicago) on December 22, 1921. He attended Columbia University, but was largely self-taught in composition, studying only briefly with Otto Luening and Darius Milhaud. After graduating from Columbia in 1948, Kurka taught at the City University of New York and Queens College, served as composer-in-residence at Dartmouth College, and composed to growing acclaim. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1951, after completing a chamber symphony, a symphony for brass and strings, a violin concerto, four string quartets, two violin sonatas, and several other works. An award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters came the following year. In 1952, he began an opera based on Jaroslav Hasek’s satirical novel The Good Soldier Schweik, but had difficulty securing rights to make a libretto from it, so instead worked his sketches into the orchestral suite that has become his best-known composition. Eventually he proceeded with the opera, but he was stricken with leukemia as he worked on the score. He was able to finish it sufficiently before his death in New York on December 12, 1957 — ten days before his 36th birthday — that composer and arranger Hershy Kay could prepare the work for its premiere, given with considerable success by the New York City Opera on April 23, 1958. The declaration accompanying an award Kurka received from Brandeis University on May 5, 1957 (seven months before his death) proved sadly ironic: “To Robert Kurka, a composer at the threshold of a career of real distinction.”

The story of Julius Caesar has served as the inspiration for some two-dozen operas. (Handel’s version of 1724 is the best known; more recent works include Gian Francesco Malipiero’s Giulio Cesare of 1936, and the 1971 puppet opera, Young Caesar, by Lou Harrison.) Shakespeare’s 1599 tragedy, Julius Caesar, which takes Caesar’s assassination as its dramatic engine, has inspired concert overtures from Robert Schumann, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Felix Draeseke, and Hermann Hirschbach; incidental music from Darius Milhaud, John Ireland, Hans von Bülow, Marc Blitzstein, Harrison Birtwistle, Vagn Holmboe, and others; and film scores from Miklós Rózsa and Malcolm Arnold. Kurka’s Julius Caesar dates from 1955; it was first heard in San Diego on July 12, 1955.

Kurka’s “Symphonic Epilogue after Shakespeare” (as the piece is subtitled) opens with an aggressive theme evoking Roman conquest and the emperor’s might. A lyrical melody suggests the drama’s more introspective moments, not least the gnawing guilt of Brutus. The build-up to what must be the moment of Caesar’s assassination is portrayed at the center of the work by a march that builds from naïve to menacing. A tragic theme and a mysterious passage, perhaps music to accompany the appearance of Caesar’s ghost, lead to a powerful, dirge-like coda.

The elements of Kurka’s characteristic musical dialect — energetic rhythms, jazz-influenced syncopations, sharply profiled themes that are developed with remarkable skill and ingenuity, kaleidoscopic orchestration, spiky but unambiguously tonal harmonies — are abundantly evident in his Symphony No. 2, composed in 1953 on a commission from the Paderewski Fund for the Encouragement of American Composers, and premiered in San Diego on July 8, 1958. The Symphony begins with a muscular theme announced by trombones, bassoons, and low strings; a broad, lyrical melody initiated by the violas and cellos provides the formal second theme. These two subjects are brought into contention as the sonata-form movement unfolds, with the dynamic first theme dominating. The outer sections of the Andante are based on a long, gentle strain of melancholy character, while the center of the movement’s arch form is more animated and expressively intense. The finale is vigorous and optimistic, its driving main theme providing the engine for a fine display of orchestral brilliance.

Kurka composed his Music for Orchestra between November 1948 and May 1949, but it was not premiered until Carlos Kalmar conducted it at the Grant Park Music Festival on June 27, 2003. The work is rather like a compressed symphonic poem: a symphonic showpiece with muscular, thematically related fast sections alternated by slower episodes.

Kurka’s Serenade for Small Orchestra (subtitled “after lines by Walt Whitman”) was commissioned by the La Jolla Musical Arts Society and premiered in that lovely California seaside town under the direction of Nikolai Sokoloff on June 13, 1954. Rather than provide a program note for the work, Kurka affixed a quotation from Whitman’s poetry to reflect the expressive essence of each of its four movements:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself;

And what I assume, you shall assume;

For every atom belonging to me as good as belongs to you.

When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d

And the great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night,

I mourned — and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring …

A song for occupations!

In the labor of engines and trades, and the labor of fields,

I find the developments,

And find the eternal meanings …

O to make the most jubilant song!

Full of music — full of manhood, womanhood, infancy!

Full of common employments — full of grain and trees.

Dr. Richard E. Rodda has provided program notes for the Orchestras of Berlin, Cleveland, Chicago, Dallas, and Cincinnati, as well as for the Kennedy Center in Washington, D. C., the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the American Symphony and Orpheus Chamber Orchestras in new York City, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Grant Park Music Festival, the Curtis Institute of Music, and many other ensembles and organizations across the country. He has written liner notes for Telarc, Sony Classical, Decca, Angel, Arabesque, Newport Classics, Delos, Azica, and Dorian. Dr. Rodda also teaches at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music.

Album Details

Total Time: 64:00

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineers: Christopher Willis & Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Front cover photo: Grant Park Music Shell c. 1940 © Chicago Park District Special Collections

Recorded: June 29 & 30, 2002 (1-4) and June 27 & 28, 2003 (5-9) in Orchestra Hall, Chicago

Publishers: All works published by G. Schirmer.

This recording is made possible in part by a generous grant from The Aaron Copland Fund for Music.

© 2004 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 077