| Subtotal | $14.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.44 |

| Total | $15.44 |

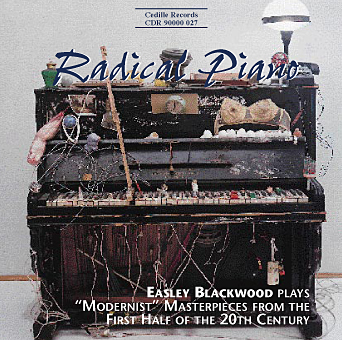

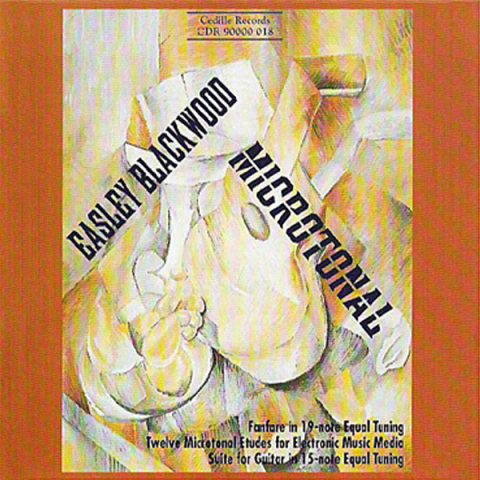

One look at the garbage-bedecked piano on the cover of Radical Piano and you know this isn’t “Dinner Classics.”

Yet this survey of early modernism is far from an assault on anyone’s aesthetic sensibilities. Pianist and composer Easley Blackwood performs a novel program of modernist masterpieces from the first half of the 20th century — nearly 75 minutes of music by modernist icons, as well as composers best known for conventional lyricism, such as Copland, Nielsen, and Prokofiev. Most of the works have rarely, if ever, been recorded.

Twentieth-century piano music has been known to provoke uprisings: listeners rise up and leave the room. Radical Piano consciously tries to hold onto the audience. One hears striking dissonances, surprising mood changes, and aggressive rhythmic elements, but nothing approaching complete atonality. It’s music that breaks the mold, without destroying the patience of mainstream listeners.

For a pleasing balance, the more dissonant works are, for the most part, separated by less dissonant ones. Stylistically, works are grouped into Russian, Western European, and American categories.

The opener, Prokofiev’s arresting Sarcasms, Op. 17, is a set of five “barbaric” and “sardonic” pieces completed in 1914. It was among a burst of defiant works composed (presumably) in response to critics who panned his adventurous First Piano Concerto. Stravinsky’s neoclassical Piano Sonata (1924) has elements of wit and caprice, as well as subtle tenderness.

American composer Blackwood acknowledges the stylistic influences of Stravinsky and Viennese-school composers Berg and schönberg in his Ten Experimental Pieces in Rhythm and Harmony (1948). Written when he was a 15-year-old student at the Berkshire Music Center, Blackwood views them today as “amusing divertimenti . . . more than mere juvenalia.” This is their world-premiere recording.

Berg’s single-movement Sonata, Op. 1 (1908), creates an elaborate “hyper-romantic” mood with its numerous frantic climaxes of increased volume and tempo. Nielsen’s ingenious Three Pieces, Op. 59 (1928), show his late interest in transitional post-tonal modernism — a radical departure from his better-known compositions. Alain’s haunting Dans le rêve laissé par la ballade des pendus de Villon (1930s) translates as “In the dream left by Villon’s Ballade of the Hanged Men.” Alain, known almost exclusively for his organ music, seems to prefigure the advent of minimalism in this rare piano composition.

Ives’ Study No. 20 (1908) contains contrasting sections of highly dissonant impressionism, followed by a hymn tune, a stately march, and a hilarious ragtime shuffle. This is the Study’s first recording expressly for CD. Lastly, Copland’s Piano Variations (1930) evinces a rugged modernism far removed from his more readily accessible compositions. “It is one of the remarkable features of the work that the same basic idea can be made to undergo such a variety of moods, ” Blackwood writes in the CD notes.

All these works make huge demands on the pianist — sudden and dramatic dynamic contrasts, tough-to-time rests, ultra-quiet passages, and virtuosic trills and runs. In Blackwood, Cedille has a pianist the Boston Globe describes as “famous for his ability to play music others dismiss as ‘unperformable’.”

Preview Excerpts

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953)

Sarcasms, Op. 17

(1914) (10:45)

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

Sonata

(1924) (10:45)

EASLEY BLACKWOOD (b. 1933)

ALBAN BERG (1885-1935)

CARL NIELSEN (1865-1931)

Three Pieces, Op. 59

(1928) (8:19)

JEHAN ALAIN (1911-1940)

CHARLES IVES (1874-1954)

AARON COPLAND (1900-1990)

Artists

9: World Premiere Recording

What the Critics Are Saying

“Easley Blackwood has proved himself again and again a musician of intelligence and taste . . . He gets inside each piece here . . . This is a stunning rendition of Copland’s Piano Variations . . . The sound is perfect for the music.”

“Blackwood . . . performs this strong recital with verve, intelligence, and world-beating technique. Cedille provides vivid sonics.”

Program Notes

Download Album BookletProkofiev’s Sarcasms, Op. 17

Notes by Easley Blackwood

The Sarcasms, completed in 1914, are among Sergei Prokofiev’s (1891-1953) first works that are entirely in his “diabolical” or “barbaric” idiom. His compositions written before 1911 are in a style that is reminiscent of Rachmaninov and early Scriabin, with the exception of the First Piano Concerto (1911), which places sections in his more modernistic idiom alongside more traditional Romantic passages. Critics found the contrast grating; and in response to their denunciation, the composer, in a burst of youthful impertinence — he was then a 21-year old student — totally embraced an even bolder modernism.

It was at this time (1912) that Prokofiev composed the first of the five Sarcasms. Barbaric outbursts and sardonic quieter passages surround a grandiose theme that rises to spectacular climaxes. The second piece is whimsical and unpredictable, and characterized by extreme fluctuations in tempo. In the third, the barbaric and sardonic styles return, surrounding a more quiet and expressive central section. The fourth piece, marked smanioso (“raving”) opens with a delirious tune, played mostly in the top octave of the piano. This is abruptly followed by a slower section featuring extreme dynamic contrasts. At the end, the opening idea returns, but pianissimo — only a furtive shadow of its former self. The final piece proceeds along much the same lines, except that the central section is a uniform, hushed pianissimo; the final variation on the beginning descends into the piano’s bottom octave, disappearing with a deep sigh.

Stravinsky’s Sonata

During the 1920s, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) toured extensively as a pianist, and composed for himself four large-scale works: the Sonata (1924), Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1924), Serenade in A for solo piano (1925), and Capriccio for piano and orchestra (1929). All four are representative of the composer’s “neo-classical” period, which begins in 1920 with the ballet Pulcinella, and closes in 1940 with the Symphony in C, coincident with Stravinsky’s departure from Europe for the United States. The works from the neo-classical period are by no means uniform in style. They frequently draw upon the styles of other composers, often with direct or thinly veiled quotes, ranging from Pergolesi (Pulcinella) to Tchaikovsky (Le Baiser de la Fée, 1928) to Rossini (Jeu de Cartes, 1936). The four works for piano are rather similar stylistically and, although not incorporating direct quotes, reveal an Italianate influence. This is especially evident in their very deliberate slow movements, which consist basically of an accompanied melody, often embellished by florid ornamentation.

The first movement of the Sonata is in sonata-allegro form, although distorted and stylized in a curiously pleasing, “Picasso-esque” manner. Stravinsky rarely uses sonata-allegro form: the only other example in a well-known work is the first movement of the Symphony in C. The second movement is essentially an A-B-A form in which the third section begins by recalling the first exactly, but then quickly departs on its own melodic course, while maintaining the same style. The final movement can be divided into five sections, of which the last is a variation on the first.

I cannot agree with critics who have characterized the Sonata as inexpressive and dry. The outer movements are witty and capricious, while the central movement is characterized by a subtle tenderness.

Blackwood’s Ten Experimental Pieces

I wrote my Ten Experimental Pieces during the summer of 1948, while I was a fifteen-year-old student-at-large at the Berkshire Music Center. This was my first concentrated musical experience; every day featured one or two rehearsals, a lecture, and a concert.

Modern music was well represented that summer, with performances of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony; Copland’s Third Symphony, El Salon Mexico, and Rodeo; Stravinsky’s Octet and Oedipus Rex; Schönberg’s Fourth Quartet; Webern’s Concerto for Nine Instruments; and numerous works by Milhaud, who was the resident composer. Especially memorable were the two concerts by the Juilliard Quartet containing the six quartets of Bartók, whose reputation was just beginning to be resurrected.

The summer of 1948 was by no means my first exposure to modern music. My family had amassed a large record collection that included works by Stravinsky, Hindemith, Prokofiev, Schönberg, and Berg. In sum, by 1948 I was already well acquainted with many of what are now considered standard works of the modern repertoire, as can plainly be heard in the Ten Experimental Pieces. The most obvious influence is that of Schönberg, especially Pierrot Lunaire and the piano pieces of Op. 11 and Op. 19. Also evident are the influences of Bartók and Stravinsky, especially in the irregularly syncopated pieces; and in several of the slower pieces, the harmonic language is reminiscent of the slower sections of the first movement of Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata.

Although I intended the pieces as abstractions, it cannot be denied that they establish moods, even though they are very brief, lasting anywhere from thirteen seconds to one minute. Moods range from dreamy impressionism to violent outbursts; and I will concede that some of the pieces are unintentionally funny — especially the ones with surprise endings.

I performed the pieces near the end of the summer at the Berkshire Festival on a composers’ forum, and the reaction to them was a mini-scandal. At the give-and-take session just after the concert, I was the only composer who received questions or comments, which ranged from incredulous to outrightly hostile — a singular experience for a fifteen-year old. The pieces now strike me as amusing divertimenti, and I hope they will be received as more than mere juvenilia.

Berg’s Sonata, Op. 1

Before his apprenticeship to Arnold Schönberg, Alban Berg’s (1885-1935) musical experience and training were minimal. He met Schönberg via a curious route: responding to an advertisement in a local newspaper. Soon their relationship went far beyond that of master-pupil, as Schönberg became a surrogate father to Berg, whose real father had died when Berg was fifteen.

Berg composed his Sonata during his period as a student of Schönberg, and it is virtually identical in overall style and harmonic idiom to the master’s contemporaneous works, in particular Pelleas und Melisande. Numerous brief motives are overlapped and intertwined to form the texture, while harmonies are often formed from whole-tone collections or superimposed fourths, while occasionally touching more conventional chords, including triads. The elaborate mood created might be described as “hyper-romantic,” especially given the numerous frantic climaxes where the player is directed to increase both volume and tempo. Quieter sections contain more reflective and impressionistic elements. The single-movement work is cast in something closely resembling a traditional sonata form; but it does not conform rigorously to the conventional Classical or Romantic succession of keys.

Nielsen’s Three Pieces, Op. 59

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) was the seventh of twelve children. His father was an artist and an amateur musician. Nielsen’s musical ability was evident at an early age: while still a boy, he played violin in his father’s band at peasant celebrations. His early life was rural, and he supplemented the family income by doing chores on nearby farms. This familiarity with nature imparts a bucolic character to many of Nielsen’s compositions.

Nielsen’s Three Pieces are among his last works, and are quite different stylistically from his better known compositions, such as the “Inextinguishable” Symphony. They are representative of his growing, if belated, interest in the transitional post-tonal modernism that is more characteristic of the turn of the century. Indeed, the use of successions of dissonant harmonies extracted from alternating whole-tone scales is quite similar to aspects of Berg’s Sonata; and the quiet, impressionistic sections of the two works have elements in common as well. However, Nielsen’s more energetic moments often exhibit a humorous aspect, which occasionally verges on slapstick, such as the “bass drum” clusters near the beginning of the third piece. Also noteworthy are the sometimes highly unexpected instances of triads. These ingenious pieces do not merit their obscurity.

Alain’s Dans le reve laisse par la ballade des pendus de Villon

Jehan Alain (1911-40) was born into a musical family and received early instruction from his father, who was a professional organist. By the age of 18, he had won first prizes at the French National Conservatory in harmony, fugue, and organ, after which his principal interest centered on composition.

The title of Alain’s descriptive work translates as “In the dream left by Villon’s Ballade of the Hanged Men.” François Villon (1431-?) was a paradoxical character: a sensitive poet with a personality prone to violence. While still a student, he killed a priest during a brawl. The church forgave him for this; but the next year, he was arrested for theft, and a series of other crimes followed. After a prison sentence, he was involved in yet another brawl, and this time condemned to the gallows as an incorrigible. His Ballade, written in 1463, anticipates his own hanging, which was to have taken place the next day. Although the sentence was annulled by Parliament, Villon fled forthwith and was never heard from again.

In the Ballade, it is the dead man who is speaking, surrounded by his condemned and hanged confreres. The most striking aspect of Alain’s grim portrayal is inspired by the lines “Never ever do we rest, but dangle, first here, then there, as the wind blows.” Along with the incessant undulating accompaniment, there is a six- note cantus firmus extracted from a whole-tone scale, heard many times, and also a chorale consisting of five seventh chords plus a final minor triad, heard three times. This latter is evocative of the line that closes each stanza of the Ballade: “Now pray to God that he might absolve us of all our sins.” It now seems an irony of fate that Alain was himself killed in action during World War II at the age of 29.

Ives’s Study No. 20

Charles Ives (1874-1954), like Jehan Alain, was born into a musical family. His father was a distinguished bandmaster who was well grounded in harmony and counterpoint by a traditional German pedagogue. From an early age, Ives received instruction from his father, and at the age of 14, became the youngest professional organist in Connecticut. In 1894, Ives entered college at Yale, where he studied with the ultra-conservative Horatio Parker while continuing his career as a church organist.

From the beginning, Ives’s peculiar fascination with polyrhythmy and polytonality set him apart as a precocious modernist, much to the disapproval of Parker and others. This led him to the realistic conclusion that a career as a professional composer was out of the question, and he instead became an actuary. At the same time, Ives continued to compose prolifically until about 1920, when he began to lose confidence. A few years later, he gave up composing altogether.

Of Ives’s 20-odd studies for piano, most are incomplete sketches, or lost altogether. No. 20 (probably composed in 1908), which bears the subtitle “Even durations — unevenly divided,” has been scrupulously edited for performance by John Kirkpatrick from a sketchy manuscript. The piece features various combinations of triplets along with twos and fours, with occasional quintuplets. After a beginning featuring contrasting sections of highly dissonant impressionism, the study gradually evolves into an accompanied hymn tune, then a stately march, and finally an outrageous ragtime shuffle. The opening sections are then recalled, but in reverse order. At the very end, the stately march trails off in the distance, and then fades out entirely.

Copland’s PIANO Variations

Aaron Copland (1900-90) is best known to concert audiences by way of his readily accessible ballets — Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring — all written between 1938 and 1945. In many other works, however, he evinces a rugged modernism, and the Piano Variations (1930) is an example of this style. The most direct and identifiable influence is that of Stravinsky, especially his Symphonies of Wind Instruments and Les Noces. This can be heard in Copland’s frequent use of clangorous major sevenths and minor ninths, and syncopations resulting from an unpatterned succession of groupings of twos and threes in a rapid tempo.

The initial statement of the theme is a slow single line, or octaves, punctuated occasionally by fortissimo dissonances. This is followed by twenty variations and a coda. The individual variations exhibit highly contrasting characteristics: sometimes solemn and meditative, sometimes violent and strident, occasionally warmly expressive, or even syncopated and jazzy. It is one of the remarkable features of the work that the same basic idea can be made to undergo such a variety of moods.

The Variations may be divided into four sections, each ending with a climax. The first concludes with variation 7 after a gradual build-up, ending on a root-position major triad — the only one to be found in the entire work. The second climax comes almost immediately, in variation 10, which is then followed by a very quiet section. The jazzy syncopations begin invariation 12, culminating in the climactic variation 17. Once again, the next climax comes almost at once in variation 20. The coda is very slow and majestic, and recalls rhythmic ideas heard earlier in variations 4 and 10, thereby imparting a sense of unity to the entire work.

— Easley Blackwood

Album Details

Total Time: 74:57

Recorded: 1994 – 96 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Piano Integral (Nam June Paik, 1963). Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna, courtesy of Holly Solomon Gallery, NYC.

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Stephen C. Hillyer

© 1996 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 027