| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

Store

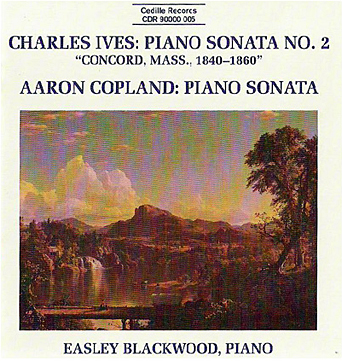

Piano Sonatas by Ives and Copland

Few pianists have had the courage to tackle Ives’ “Concord” Sonata in public. Easley Blackwood made it his signature piece. Blackwood earned high praise for his concert performances of Ives’ “Concord” Sonata, a set of transcendentalist meditations named for Emerson, Hawthorne, the Alcott family and Thoreau, all of whom lived in Concord, Mass. Critic Max Harrison of The London Times declared Blackwood’s performance of the piece “the finest account I have ever heard.”

Chicago Symphony Orchestra flutist Richard Graef, a Blackwood colleague in the Grammy Award-winning Chicago Pro Musica chamber music ensemble, performs in the sonata’s “Thoreau” movement.

Copland’s Piano Sonata, long overshadowed by his populist works, represents his most profound and personal thoughts. A surprisingly lively middle movement explores fast rhythms in irregular, rapidly changing meters. “I never would have thought of those rhythms if I had not been familiar with jazz,” Copland remarked.

Preview Excerpts

CHARLES IVES (1874-1954)

Piano Sonata No. 2, "Concord, Mass., 1840-1860"

AARON COPLAND (1900-1990)

Piano Sonata

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAmerican Voices: Piano Sonatas by Charles Ives and Aaron Copland

Notes by Anne Shreffler - University of Chicago

The Second Piano Sonata of Charles E. Ives (1874-1954), subtitled “Concord, Mass., 1840-60,” sprawls over four movements filled with gestures of tremendous complexity and density, and exhibits an unprecedented scope of ideas. The more spare Piano Sonata by Aaron Copland (1900-1990), on the other hand, articulates its three movements in half the time of the Ives, with characteristic economy and restraint throughout. Yet both works are products of composers considered typically American; the biographies of both men resonate with an almost mythical ring: Ives, the Yale-educated businessman who, in his spare time, composed music many at first considered incomprehensible, and Copland, the son of Jewish immigrants, whose music melds the sounds of folk song and dance into what became accepted as a national American music. Are both ‘typically American’? Yes, though one speaks an inner-directed language that brings together musical ideas of many levels into a complex web, while the other fashions a more consistent discourse meant to be immediately intelligible. Ives’s is the private voice of American music; Copland’s the public one.

Though composed many years apart, both the Ives Concord Sonata and the Copland Piano Sonata were brought to the attention of the public within five years of each other by pianist John Kirkpatrick, who remained a lifelong advocate for both works. When Kirkpatrick premiered the Concord Sonata in New York in 1939 (some twenty-five years after its composition), Lawrence Gilman of the New York Herald Tribune praised the work as “exceptionally great music, indeed, the greatest music composed by an American.” Kirkpatrick’s performance of Copland’s Sonata four years later won mixed reviews from the press, but unreserved admiration from others, most notably Leonard Bernstein, who later called the piece his favorite Copland composition.

The four movements of Ives’s Concord Sonata provide sketches of the Transcendentalist thinkers Emerson, Hawthorne, Alcott, and Thoreau. The piece occupies a place of central importance in Ives’s output, both musically and philosophically. Recog-nizing its rugged complexity, Kirkpatrick called it ‘the maddest music imaginable.” The compositional history of the “Concord” is equally complex; its dates of origin, composition, and revision remain obscure. Portions of the Sonata are drawn from earlier works, for example the 1907 Country Band March that emerges in the second movement. Most of the actual composition took place in 1911 and 1912. Several years later, Ives prepared the score for self-publication, and presented the first edition in 1920, along with a separate volume of explanatory prose, entitled Essays Before a Sonata. The composer subsequently drew upon material from the Sonata for other works, for example the song ‘thoreau,” which is based on the fourth movement. Ives continued to revise the Concord, however, and Arrow Press published a second edition in 1947. Ives apparently could not leave the piece alone even then; there is evidence that he made notations for still more revisions during the last year of his life. As with most of Ives’s compositions, the concept of a “finished work” is hardly applicable here. Ives explained, “…every time I play it or turn to it, [it] seems unfinished.”* When Ives played the piece for a friend in 1912, he admits he improvised in a few places. Correspondingly, Ives urged Kirkpatrick to “do whatever seems natural or best to you, though not necessarily the same way each time.”

The ongoing composition and revision of the Concord Sonata is best considered not as an anticipation of a Cageian “open form,” but as a natural analogue to the developmental processes on which the work is based. Throughout his life, Ives resisted standard musical forms like sonata, theme and variations, and fugue, believing instead that the music should be allowed to find its own design. Ives explained (with characteristic pithiness): ‘that a symphony, sonata, or jig… should end where it started, on the Doh key, is no more a natural law than that all men should die in the same town and street number in which they were born.” For Ives, musical form was based on process, not structure. He was fond of comparing form and design in music to the experience of a mountain climber; as the hiker ascends, his perspective changes and both ground and sky look progressively different.

Such “progressive” form can be seen in the first movement, entitled “Emerson.” The beginning features two voices moving outwards in contrary motion from a central point; the vast spaciousness of this gesture opens out to the most dense and metrically free music in the piece, imbedded in which we find the opening motive from Beethoven’s Fifth, which plays a prominent role in all four movements. As the movement continues, meter becomes occasionally clearer, and themes can now be more easily identified. There follows a quieter, more regular passage marked “Verse,” in contrast to the opening, which was marked “Prose.” Ives originally conceived of the “Emerson” material as a piano concerto; vestigial concerto-like features remain in the alternation between “prose” and “verse” passages, and in the cadential gestures that begin the piece. The movement’s conclusion is serenely contemplative: over slow-moving octaves in the bass can be heard a hymn tune, the first three notes of which match the Beethoven motive. Rather than adhering to an expository formal scheme, the music bursts out in chaos and gradually coalesces into lucidity. The result, according to Ives, precisely parallels Emerson’s thought. In the Essays Before a Sonata, Ives points out that Emerson’s prose may seem incoherent because of the intensity and complexity of the ideas he is trying to express:

Emerson wrote by sentences or phrases, rather than by logical sequence. His underlying plan of work seems based on the large unity of a series of particular aspects of a subject, rather than on the continuity of its expression. As thoughts surge to his mind, he fills the heavens with them, crowds them in, if necessary, but seldom arranges them along the ground first….

According to Ives, the Concord’s second movement, “Hawthorne,” “is fundamentally a Scherzo, a joke… the opposite of Emerson, which is serious, goes to the deeper things.” In this movement, Ives portrays not the serious, Puritan side of Hawthorne’s character, but tries instead ‘to suggest some of his wilder, fantastical adventures into the half-childlike, half-fairylike phantasmal realms.’ We have for this movement a much more detailed program than for the others. In several printed copies of this first edition, and in letters to friends, Ives noted how specific passages refer to events in Hawthorne’s short stories. For example, the rapid delicate motion at the beginning of the movement represents ‘magical frost waves on a Berkshire dawn window’; a repeated sixteenth-note figure in the bass a little later, the ‘celestial railroad’ (a theme prominent throughout the movement); a pentatonic-sounding passage, ‘demons dancing around the pipe bowl’; and soft tone clusters played with a long felt-covered wood block, the sound of distant church bells. Other passages seem to recall Ives’s own childhood in Danbury, Connecticut more than Hawthorne’s stories. Hence the intrusion of a boisterous Ab major march complete with a pianistic ‘drummer’s roll-off’ and the later emergence of the patriotic tune “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” a theme found in many Ives works.

The third movement is not about a single person, but a family. Ives writes , “We dare not attempt to follow the philosophic raptures of Bronson Alcott….” So Ives portrays ‘the memory of that home under the elms… [where] Beth played the old Scotch airs, and played at the Fifth Symphony.’ Thematically, the movement presents the clearest statements yet of the Beethoven Fifth motive and the related hymn, “Martyn” (also known as “Jesus Lover of My Soul”); almost every note is drawn either from these themes or from the ‘scotch airs.’ In depicting the serenity of the family circle, Ives eschews the surface complexity of the earlier movements (this is also the shortest of the four). Only briefly, once in the middle and again at the very end, does the movement become clamorous; this, Ives explains, is where “Bronson Alcott gets to talkin’ loud….”

About ‘thoreau,” Ives writes: “if there shall be a program let it follow his thought on an autumn day of Indian summer at Walden….” Rather than a comprehensive portrait of either Thoreau as a person or of his philosophy, Ives depicts instead Thoreau’s (and all mankind’s) relationship to nature. The movement can be heard as a shorter echo of Emerson. Like the first movement, its form is progressive; the improvisatory gestures of the beginning settle, over time, into music of tranquil clarity. Moreover, Ives instructs the performer that the whole movement is to be played more quietly than the rest of the piece. Perhaps the most unusual aspect of this movement is the unexpected entrance of a solo flute quietly intoning the Martyn hymn. Here Ives literally depicts ‘the poet’s flute… heard out over the pond,’ and asks, “Is it a transcendental tune of Concord?”

Like Ives, Aaron Copland reserved his most serious musical thoughts for the piano. In a trilogy of important keyboard works, the Piano Sonata (1939-41) forms an accessible oasis between the thorny, almost atonal Piano Variations of 1930 and the ambitious twelve-tone Piano Fantasy completed in 1957. Yet the Sonata has been relatively neglected, perhaps because it has been eclipsed by the extremely popular works Copland wrote during the same years: film scores for Of Mice and Men and Our Town, the Lincoln Portrait, and the ballets Rodeo and Billy the Kid. That the Sonata survives at all is remarkable; in June of 1941, a suitcase containing Copland’s only copy of the score was stolen and never recovered. Over the following months, he reconstructed the piece from memory, with the help of John Kirkpatrick, for whom he had once played it. Copland performed the world premiere that fall in Buenos Aires.

Copland’s music represents a side of American expression opposite that of Ives. The Piano Sonata is not extravagant, but plain; Puritan rather than transcendental. Although the piece is certainly enjoyable on first hearing, Copland was aware of its austere quality. He explained in his autobiography that full appreciation required repeated listenings and careful study; this was worthwhile, however, because “every note was carefully chosen and none included for ornamental reasons.”** The outer sections of the first movement feature sonorous chordal writing so dense it sometimes appears on four staves. Contrasting with these is a quick middle part that indulges in inventive rhythmic play entirely in unisons and octaves. The second movement, marked Vivace, explores fast rhythms in irregular, rapidly-changing meters. Although the movement is not overtly reminiscent of jazz, Copland acknowledges, “I never would have thought of those rhythms if I had not been familiar with jazz.” In the third and final movement, Copland returns to the chordal sonorities and slow tempos of the beginning. One striking feature of this movement is how Copland often reduces the texture to one or two parts, presenting song-like material. These passages do not contain actual quotations, but do bear the contours and mood of American folk ballads. (Perhaps this reference to folk material is Copland’s way of paying a subtle homage to Ives.) The work ends with an extended, very slow-moving passage of wide leaps in both hands, marked “elegiac.” Copland writes that he did not want to end with ‘the usual flash of virtuosic passages; instead, it is… grandiose and massive.’ Not a populist work like Rodeo or Lincoln Portrait, the Piano Sonata instead represents Copland’s most profound and personal thought.

– Anne Shreffler

University of Chicago

*All quotations from Ives come from either Charles E. Ives: Memos, ed. John Kirkpatrick (New York: Norton, 1972), or Charles Ives: Essays Before a Sonata, The Majority, and Other Writings, ed. Howard Boatwright (New York: Norton 1961).

**Quotations from Copland come from Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, Copland: 1900 through 1942 (New York: St. Martin’s/Marek, 1984).

Album Details

Total Time: 66:19

Recorded: January 10-12, 1991 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: New England Scenery (Frederic Church, 1851). George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Mass.

Design: Robert J. Salm, STATS-IT, Inc.

© 1991 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 005