| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

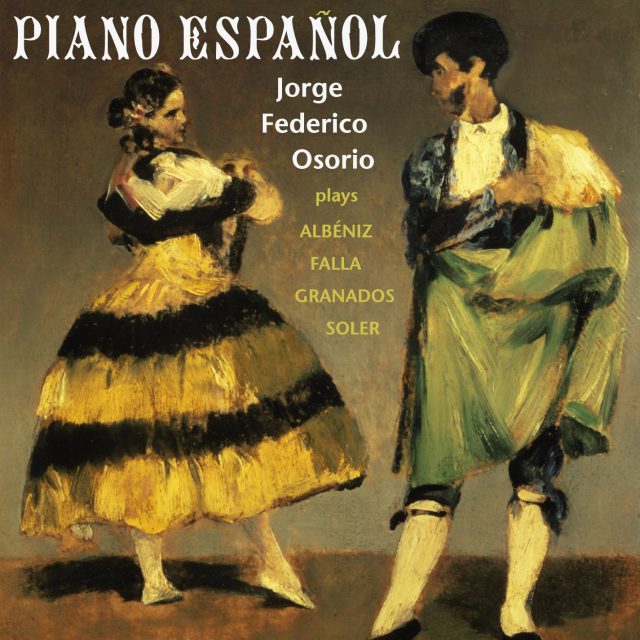

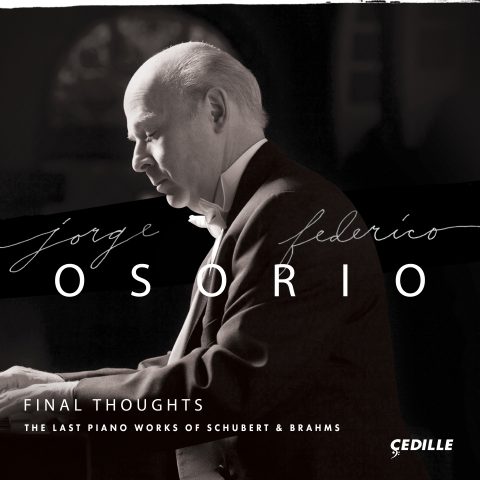

Jorge Federico Osorio, a widely recorded and much-honored international concert pianist, makes his Cedille Records debut this month with his first recording devoted to solo piano music by Spanish composers.

On Piano Español, the Mexico City native, now living in the Chicago area, performs Manuel de Falla’s theatrically tuneful Piezas Españolas, Isaac Alebniz’s panoramic Suite Española, No. 1, four sprightly and elegant sonatas by Antonio Soler, and selecred Danzas Españolas by the “Spanish Chopin,” Enrique Granados. Osorio calls it a program “for sheer enjoyment, for the beatuy and the colors and the rhythym.”

Preview Excerpts

MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946)

Piezas Espanolas

(1908) (16:30)

ISAAC ALBENIZ (1860-1909)

Suite Espanola No. 1

(33:45)

PADRE ANTONIO SOLER (1729-1783)

ENRIQUE GRANADOS (1867-1916)

Danzas Espanolas

Artists

What the Critics Are Saying

“10/10 — This splendid recital adds up to more than the sum of its various parts. At 78 minutes it’s also a very good deal. Jorge Federico Osorio knows this music as well as any pianist alive, and his performances bespeak the wisdom of maturity with no loss of freshness or spontaneity…. There’s poetry aplenty, but also bravura. Sonically this recording strikes me as ideal. In short, what you hear is what Osorio does, and what he does is pretty terrific.”

“Make no mistake about it, Osorio is a major pianist, and this handsome collection of Spanish masterpieces is proof of that fact…. If you want the best possible introduction to Spanish piano classics, played by the successor to de Larrocha, get this gorgeous-sounding recording.”

“Choosing one highlight over another is impossible in a recording of such sustained excellence.”

Program Notes

Download Album BookletPiano Español

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

A map of the Iberian Peninsula shows its unique geographical position between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, reminding us of the historic seafaring achievements of Spanish and Portuguese explorers who reached India by sailing around the southern tip of Africa, ventured westward to find the Americas, and eventually circumnavigated the globe. Back at home, so to speak, another geographical feature jumps out at us from the map of Spain: it is crisscrossed by numerous mountain ranges, forming natural divisions and barriers which, for many centuries, worked against the formation of a unified country. Even today, Spain remains a nation of distinct regions with their own cultures, including their own musical traditions. The history of Spanish music is woven from many threads, creating a rich and complex tapestry.

A more homogeneous element in Spain’s musical history stems from the strong influence of the Roman Catholic Church, whose cathedrals and monasteries possess vast libraries of sacred music. Among their treasures are the medieval Huelgas Manuscript, the Cantigas of Alfonso the Wise in praise of the Virgin Mary, the motets of Tomas Luis da Victoria and his Renaissance-era contemporaries, and the elaborate Baroque Mass settings whose style emigrated overseas to become part of the heritage of Hispanic-American composers.

Also from early days come innumerable works for the guitar and its predecessor, the vihuela, plus instruction books for playing on and composing for them. The quintessential Spanish instrument, used in both popular settings and the elegant surroundings of noble courts, the guitar accompanied singing and dancing, and starred on its own in a repertory of purely instrumental variations and fantasies on tunes old and new.

Though somewhat isolated from the rest of Europe, Spain was hardly immune to influences from across the Pyrenees. By the 18th century, Italian opera had caught on in the principal musical centers: Madrid, the centrally located capital, and Barcelona, the Catalonian metropolis located on the northeastern Mediterranean coast. Two representatives of the Italian instrumental tradition, keyboardist Domenico Scarlatti and cello virtuoso Luigi Boccherini, had major careers in Spain during the 1700s, each in the service of royalty. They brought with them the styles and procedures then current not only in Italy but also in German-speaking lands. At about the same time, there emerged a native Spaniard of great creativity and originality who became one of the major composers and music theorists of his time.

Antonio Soler (1729–1783) was born in Catalonia the same year that Scarlatti arrived in Spain as tutor and musician-in-residence for Queen Maria Barbara. A virtuoso organist who took holy orders, Padre Soler was trained at the distinguished music school of the monastery in Montserrat, an institution that remains renowned to this day. Naturally, he wrote several masses; he’s also credited with over 100 villancicos: secular pieces that combine song and dance to tell a story, often associated with Christmas. Despite this considerable output of vocal music, it is almost exclusively for his inventive keyboard sonatas that Soler is celebrated today.

Although it’s unclear whether he ever studied with Scarlatti, Soler certainly knew the older man’s harpsichord sonatas and was influenced by them. Soler constructed his own works in the genre using the same two-section framework, each section usually repeated,[1] the second portion ending in the same key in which the first portion began. It’s not entirely clear whether Soler composed his sonatas primarily for harpsichord or for the newer keyboard instrument of his day, the fortepiano, but, either way, they adapt beautifully to the modern piano.

Soler’s sonatas moved beyond Scarlatti’s in the originality and ingenuity of their key relationships and modulations. Soler’s route from home key to home key wanders through both major and minor modes, and even through keys only remotely related to home base. On this CD, the Sonata in D major explores A major, A minor, and G minor before returning, through rapid chromaticism, to D. The D-flat Sonata’s rapid figurations touch on several keys at least briefly.

This adventurousness with key relationships reflects Soler’s fascination with one of 18th-century music’s technical innovations: the tempered, or equalized, tuning of keyboard instruments. Because the relationships between all 12 intervals of the chromatic scale had been evened out to exact half-tones (C to D on the piano is a whole tone; C to C-Sharp is a half tone), composers could, for the first time, use near-constant modulation to enrich and enliven keyboard music. Bach’s similar fascination with the new tuning system led to his Well-Tempered Clavier, one of the great documents of keyboard music: two sets of preludes and fugues in all possible major and minor keys. In a sense, Scarlatti’s and Soler’s voluminous collections of sonatas constitute analogous achievements.

Snugged into the northeast corner of the Iberian Peninsula, Catalonia has long been famous for creativity in both poetry and music, and for linguistic individuality. (A Catalan tongue distinct from Spanish survives to this day.) It is therefore perhaps not coincidental that Soler, Albeniz, and Granados were all Catalan, as was Falla’s mother (although Falla was born in Cadiz). Yet another Catalan, Felipe Pedrell (1841–1922), was a leader in the revitalization of Spanish music in the late 19th century. A musicologist who catalogued both sacred and secular music, Pedrell helped establish a nationalist tradition in the country’s music that merged folksongs, traditional dances, and age-old guitar stylings into the forms and genres of concert music. This nationalist trend in Spanish music paralleled those in many other countries, including Russia, Bohemia, Hungary, Finland, Norway, England, and ultimately the United States. Albeniz and Granados both studied with Pedrell, who inspired them — and, indirectly, the slightly younger Falla — to celebrate Spanish sounds in their works. All three composers admired Pedrell profoundly.

Although best remembered for his stage works — El Amor Brujo, La Vida Breve, and especially The Three-Cornered Hat — Manuel de Falla (1876–1946) was trained as a pianist at the Madrid Conservatory, made his first public appearances as a pianist, and taught the instrument to earn a living while establishing himself as a composer. In 1907, he moved to Paris, where he renewed his acquaintance with Albeniz and made new friends, including Debussy, whose style influenced him nearly as much as his assimilation of Spanish idioms. Completed in 1908, the Piezas Españolas were premiered in Paris the following year by the outstanding pianist Ricardo Vines, a friend and collaborator of Ravel. They bear a dedication to Albeniz.

While the pieces have descriptive titles, they’re not necessarily direct quotations of folksongs. “Instead of strictly making use of popular songs,” Falla wrote, “I have extracted from them their rhythm, their modality, their ornamental motifs, their modulatory cadences.” The first piece is labeled Aragonesa, from Aragon, a region of northeastern Spain that abuts Catalonia and whose characteristic triple-meter dance is the jota, performed traditionally with castanets and guitars. Falla said: “I have not adopted a single authentic jota, but I have tried to stylize the jota.”

We move farther afield for Cubana, evoking the recently-independent Spanish colony in a part of the world Falla would not visit until years later: he died in Argentina in 1946, having left Spain after its civil war in the 1930s. Cubana‘s rhythm is that of a guajira, a dance that shifts between faster- and slower-paced triple meters. Montanesa (Mountains, subtitled Landscape) evokes the atmosphere of the Spanish highlands. The concluding Andaluza takes us to the sights and sounds of Spain’s most southerly region, with strong echoes of flamenco guitar playing and brilliant Andalucian sunshine.

Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) was a virtuoso pianist through and through, which makes it somewhat ironic that so many of his piano pieces are heard nowadays more often on guitar, and that his monumental keyboard masterpiece, Iberia, has become better known in its orchestrated version. His compositions, created mainly for his own performing purposes, translate well to the guitar because most of them were inspired by Spain’s guitar-playing tradition. Hearing them on piano, however, demonstrates just how brilliantly they suit their original medium. Likewise, Albeniz’s tone colors and rhythms on the piano (an instrument he knew intimately from earliest childhood) can easily be exploited in an orchestral medium to create lush tone poems.

Completed in the 1880s, the movements of Suite Española form a kind of musical atlas of Spain. All eight pieces are in triple meters; all except Cataluña are in ternary (three-part) form, with two related sections framing a contrasting central portion. In Spanish musical terminology this midsection is called a copla, originally an improvised sung interlude within a dance piece.

First in the suite, Granada is a lyrical instrumental serenade, evoking the great Andalucian city whose history and architecture recall the culture of Spain’s medieval Moorish community. “Cataluña,” writes critic Lionel Salter, “[is] the only occasion, apart from the later orchestral ‘Catalonia,’ that Albeniz ever made musical reference to his native region. [It] is a ‘corranda,’ a somewhat mournful 6/8 dance.”

Another great city of the southern Andalucian landscape is Seville, honored in movement three through the rhythms of a flamenco-like dance called Sevillanas. Continuing to explore Andalucia, we next visit the southwestern coastal city of Cadiz, for a movement subtitled Saeta. This is a type of song, originally improvised, that is sung during religious processions.

With Asturias, subtitled Leyenda (Legend), we come to perhaps the best-known piece in the suite, particularly popular in transcription as a guitar solo. When we hear it on the original instrument, however, we’re instantly struck by how very pianistic it is. Leyenda is a remarkable creation, idiomatic to two very different instruments, demanding in its virtuosity, and producing an extraordinarily atmospheric effect. What the legend is we don’t know, but the music tells us clearly that it’s a haunting tale. The rapid figurations of the outer sections recall the flamenco tradition, from which comes also the improvisatory, song-like theme of the copla.

Now we travel once again, as we did at the start of Falla’s suite, to the landlocked northeastern region of Aragon, and hear another interpretation of its native jota. Albeniz subtitles this movement Fantasia, and explores its themes in a free-form style with many contrasts of mood.

The union of the ancient realms of Aragon and Castille, through the 15th-century marriage of two famous monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, led (after many centuries) to the foundation of a unified Spain. Movement seven of Albeniz’s suite is Castilla, and the dance type is a seguidilla, rapidly-paced and traditionally accompanied by castanets. The finale of Suite Española is Cuba, a land Albeniz visited as a teenage wanderer after he ran away from home and supported himself by playing piano in cafes in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the United States. Cuba is subtitled Capriccio, a term with no real musical definition, but its analogy to the English word “capricious” adequately describes the mood of the piece.

Seven years younger than Albeniz, Enrique Granados (1867-1916) likewise studied with Pedrell and, like both Albeniz and Falla, spent significant time in Paris. He won fame as an opera composer as well as for the music he wrote for his principal instrument, the piano. These disparate musical formats are linked through the work most commentators cite as his masterpiece. Inspired by his love for the paintings of Francisco Goya, Granados originally wrote Goyescas as a piano suite and later turned it into an opera. The planned premiere at the Paris Opera was cancelled because of the abrupt outbreak of World War I in 1914. New York’s Metropolitan Opera staged the eventual premiere in 1916. Returning to Europe from that event, Granados and his wife died aboard a British ship that was sunk by a German torpedo.

Granados created a large-scale keyboard masterwork before Goyescas: he penned his suite of twelve Danzas Españolas in the 1890s, initially as four separate sets, but later published all together as his Op. 37. As with Albeniz’s Iberia, several of the Danzas were orchestrated. This CD contains the original piano versions of four of the dances, beginning with the short Minueto in G Major that Granados dedicated to his future wife, Amparo Gal.

Dance No. 2, titled Oriental, evokes not China or Japan but the atmosphere of Moorish Andalucia. Expelled from Spain in the Middle Ages, the Islamic Moors left strong imprints on Spanish music, art, poetry, and architecture. In its piano version and in its subsequent orchestral arrangement, Oriental breathes forth the subtle flavor of Andalucia’s exotic erstwhile residents.

Dance No. 5, the most familiar of the set, has been arranged for many different instrumental settings, including (of course) guitar. Once again we are surrounded by the warm, languorous nights of Andalucia and its haunting Moorish echoes. To end, we again hear the bright rhythms and colors of the Aragonese jota, this time in D Major, starting at a moderate pace but growing ever faster and more intense, leading to a thrilling conclusion.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

[1] Mr. Osorio chooses not to play repeats in the two slower sonatas on this recording.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:30

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover: Spanish Dancers, 1879 (oil on parchment) Edouard Manet (1832-1883)/ Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded: July 10 & 11, 2003 at WFMT, Chicago Steinway Piano & Piano

Technician: Ken Orgel

Microphones: Sennheiser MKH 40, Schoeps MK 21

© 2004 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 075