| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

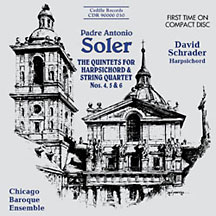

Padre Antonio Soler: Quintets for Harpsichord and Strings Numbers 4-6

David Schrader, Chicago Baroque Ensemble

Padre Antonio Soler’s six quintets for harpsichord and string quartet are post-Baroque masterstrokes, blending Baroque and early Classical styles with a savory seasoning of Spanish folk music.

The complete quintets are represented on two CDs, sold separately, and are the only currently available recordings in any format of Soler’s quintets, according to the fall 1996 Schwann Opus catalog, and form the first complete set on CD. (The first three quintets are available on Volume I.)

“In terms of crowd-pleasing qualities, the last three quintets of Soler may even eclipse their predecessors,” says record producer James Ginsburg. “Yet they also reward the serious listener.” In fact, Ginsburg suggest that newcomers may want to start with the second and newest Soler CD, and then, if it whets their appetite, pick up the earlier CD.

While formally less diverse than the first three quintets, the latter three are especially lyrical and offer a stimulating variety of moods and timbres which — at least in the hands of the present performers — evoke the sound of woodwinds, chimes, harp, and even Spanish guitar.

Cedille undertook the Soler quintets because they represent neglected yet pleasurable repertoire — the label’s hallmark — and in Schrader, Cedille found a Chicago-based artist who championed Soler and could be counted on to give a world-class reading, Ginsburg says. The Chicago Baroque Ensemble, two of whose members performed on the first quintets CD, is a relatively new organization that testifies to the quality and depth of Chicago’s period-instrument community.

Though rare even on LP, Soler’s quintets charmed listeners of the vinyl era. American Record Guide (October 1964) deemed the Quintet No. 6, on Westminster Records, “well off the beaten track of repertoire” and of “considerable musical as well as historical value,” with “lovely moments that are worth savoring for themselves.” Reviewing a Vox LP set of the complete quintets, Stereo Review‘s Richard Freed wrote (October 1973), “All six of these are really so endearing that it would take a hard heart to resist the set, once exposed to it.” Paul Henry Lang, in High Fidelity (October 1973), called them “charming, melodious, and euphonious compositions.”

Preview Excerpts

PADRE ANTONIO SOLER (1729-1783)

Quintet No. 4 in A Minor

Quintet No. 5 in D Major

Quintet No. 6 in G Minor

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Keyboard Quintets of Soler

Notes by David Schrader

Antonio Francisco Javier Jose Soler y Ramos was baptized on December 3, 1729. Destined for a career in the church, in 1736 he entered the choir school of the great Catalan monastery of Montserrat, where he studied with the monastery’s Maestro, Benito Esteve, and its organist, Benito Valls. After becoming Maestro de Capilla, or Music Director, at Lerida circa 1750, Soler was ordained to the subdiaconate in 1752. He entered the Hieronimite monastery at El Escorial, the large palace and college cum monastery established a century and a half earlier by King Philip II, taking the habit on September 25, 1752. Soler became Maestro de Capilla at El Escorial in 1757, upon the death of the incumbent maestro, the redoubtable Domenico Scarlatti. The monastery’s extant records, or actos capitulares, note that Soler had an excellent command of Latin, organ playing, and musical composition; his conduct and application to his discipline were said to have been exemplary.

Soler is known for his theoretical writings, which, in addition to the famous Llave de le modulacion (key to modulation) of 1762, even include a treatise on the conversion rates between Catalan and Castilian currencies. While the principles contained in the Llave are still recognized as valid, it is well to note that the modulations were considered radical enough in eighteenth century Spain to elicit critical rebuttal, to which Soler himself responded with a 1765 tract entitled Satisfacción a los reparos precisos (reply to specific objections).

Like Domenico Scarlatti, Soler also enjoyed the patronage of a member of the royal family: Prince Gabriel, the son of Charles III. Soler wrote many of his solo keyboard sonatas for the prince, who was also quite likely the inspiration for Soler’s six concerti for two organs and his six quintets for keyboard and strings.

The source for Soler’s quintets for keyboard and string quartet is a manuscript found in the archive for the Maestria de Capilla, or Music Directorship, at the Escorial. It consists of five notebooks which in turn give us the full scores and the individual string parts for the quintets. The score for the first quintet is inscribed:

Obra primera

Quinteto primera con violinos, viola, violoncelo y organo o clave obligado.

Para la Real camara del Serenissimo Señor Infante Don Gabriel Compuesta i dedicada a su Alteza Real por el Fray Antonio Soler. Ano 1776.

(First work, first quintet with violins, viola, violoncello and obbligato organ or [other] keyboard. For the royal chamber of the Most Serene Lord Prince Gabriel, composed and dedicated to His Royal Highness by Father Antonio Soler in the year 1776.)

Although Soler is primarily identified with the baroque tradition, his incipient classical bent is well favored in these remarkable quintets. Like many of Soler’s later sonatas for solo keyboard, the quintets are multi-movement pieces. While Soler does not follow the standard sequence of movements employed by Viennese classicists of the time, the character of the music itself is largely reflective of the esthetic of the latter part of the eighteenth century. Although this is not confirmed, scholars believe that Soler had some familiarity with the work of Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805), who lived in Madrid from 1769 to 1785, after having spent his formative years in Vienna in the late 1750’s and 1760’s. This would offer a precedent for the skillful string quartet writing found in Soler’s quintets. The imaginativeness of Soler’s writing often defies contemporary parallels, however, suggesting that Soler may have conceived these quintets with only the most superficial knowledge of classical traditions outside of Spain.

The keyboard parts are composed in a style similar to that of Soler’s sonatas for solo keyboard. The cleverness, elegance, and mercurial virtuosity of those sonatas are encountered in the quintets as well. The keyboard parts of the quintets heard on this recording abound with the rapid-fire ornamentation and the minute detail that typify Soler’s keyboard style. Although this recording employs a harpsichord, the title page also suggests the use of a chamber organ. The organ, according to indications given in the score, seems to have had two keyboards (or at least some sort of mechanical device capable of producing echo effects) and several different registers such as regals (“buzzy,” short-resonator reeds) and a “flautado,” or principal register.

The Fourth Quintet, in A Minor, is composed in four movements: Allegretto, Minuetto I and II, Allegro assai, and a concluding Minuetto con variazioni. The first movement employs an agile theme first heard in the strings—a downward scale with quick trills. This idea is expanded upon throughout a sizable opening “tutti,” as it were, and is then taken up by the keyboard. The strings and keyboard act in dialogue joining forces only occasionally to produce a movement that, while meeting the harmonic requirements of classical sonata form, does not develop its thematic material in the way that is customarily associated with that form. The first Minuetto is played by the strings; the second by the keyboard alone.The musical language of the Allegro assai is largely reminiscent of the solo sonatas of Scarlatti and Soler. The movement is intense and dancelike, composed in 3/8 time. Again, classical form is not really fully developed—the ideas found in the opening section, played by the strings alone, are worked out using the late baroque practice of “spinning out,” rather than in the mature classical manner. The final Minuetto and its variations feature various combinations of string instruments by themselves, sometimes incorporating highly virtuosic material into their texture. The keyboard is heard by itself as well as in dialogue and in concert with the strings.

The Fifth Quintet, in D Major, begins with another massive section played by the strings. The texture then changes with the entrance of the keyboard, which initiates a wonderful, sonata-like dialogue with the muted first violin. This pattern of alternating solo (keyboard and first violin) and tutti sections forms a delicate chain of ritornello and solo passages that calls to mind concerti of the middle of the eighteenth century. With the following Allegro presto, the hearer is once again reminded of the sounds and style of Soler’s keyboard sonatas. The tempo is very quick—the passages for strings alone are often punctuated by vigorous and percussive triple-stops for all four players (no, this does NOT add up to composition in twelve notes!), and the keyboard is heard chiefly in contrast to the strings, again reminiscent of concerto writing. The next movement, a Minuetto (how did you guess?), suggests the sound of folk instruments because of the drones played by the viola and ‘cello. The contrasting section that follows is not called a second Minuetto or a Trio, but a Quartetto, in which the ‘cello is not heard. The keyboard and the first violin play a dialogue accompanied by the delicate pizzicati of the second violin and the viola. The work concludes with a Rondo and variations.

The Quintet in G Minor operates on two very distinct ideas: a lyrical theme is developed in the strings is answered by a surprising change in tempo and character when the keyboard enters. The contrast of muted and unmuted strings is used as in the fifth quintet. These two contrasting ideas work out to a beautifully symmetrical form—slow-fast-slow-fast-slow, with the keyboard entering only during fast sections, and then joining with the strings to end the movement. The next movement consists of a Minuetto in dialogue between the strings and keyboard and a Quartetto, First Violin: Anonymous, Mirecourt, mid-18th century Second Violin: Anonymous, Tirol, c. 1720 Viola: Nathaniel Cross, England, 18th century Cello: Jacobus Horil, Rome, 1750 this time for the strings alone. The final movement is a gracious Rondo with twelve variations—the instruments are heard in a wide variety of combinations, ultimately joining together to replay the theme in its initial form.

The fourth, fifth, and sixth Quintets are formally not quite as diverse as the first three—there is no use of the “intento,” or fugue in the last three. The keyboard writing is gracious, but not as virtuosic as in the C Major (no. 1) Quintet, in which one encounters some rather fiendish cross-hand writing. Nevertheless, the last three display a tightness of form that is indicative of a very sure hand—could it be that the experiments of Quintets one, two, and three were abandoned in favor of the devices that seemed to work so well in numbers four, five, and six? In any event, the last three Quintets all contain elements that are typical of concerti written during the 1760s and 70s—all in Soler’s unique and curious language that unites the musical characteristics of Spanish folk music with the more rarified atmosphere of the court.

One note regarding repeats: All are observed, except for the long theme and variations third movement of Quintet No. 6, where only the theme at the beginning (both halves) is repeated.

— David Schrader

Album Details

Total Time: 74:57

Recorded: May 25-28, 1996 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Facade of the Basilica at El Escorial. Ink drawing by Jack Simmerling.

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: David Schrader

© 1996 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 030