| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

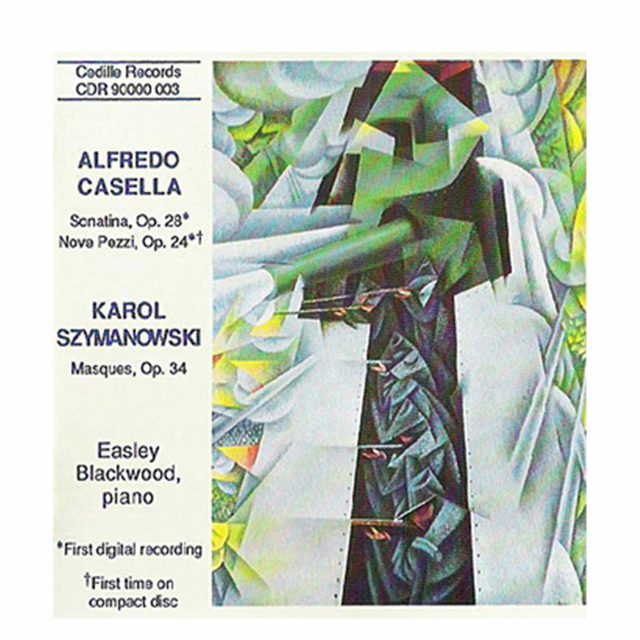

Pianist Easley Blackwood, celebrated for his performances of transcendentally difficult modern works, made his solo recording with this imaginative excursion through works by two early modernists.

The program combines works by Italian composer Alfredo Casella and Polish master Karol Szymanowski. Both absorbed the cosmopolitan influences of pre-World War I Paris, Vienna and Berlin. With the outbreak of war, both retreated into isolation in their homelands and began to write their finest music.

As Easley Blackwood elaborates in his notes: “The pairing of the Italian composer Alfredo Casella and the Polish Karol Szymanowski is not as unlikely as it might seem at first glance. Both absorbed the cosmopolitan influences of pre-World War I Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, and correspondingly were at first thoroughly committed to an international modernism. Both were active in promoting the new music of the day in their own countries, later to become ardent patriots who absorbed and helped to redefine the musical heritage of their respective lands. Both Casella and Szymanowski, like Stravinsky, Berg, Webern, and Bartók, were born in the early 1880s, and came to maturity just before the First World War. The relatively stable social and political situation before the war enabled a whole generation to spend its formative years in an environment highly conducive to cross-fertilization and interaction among artists and patrons. Once the war started, most were forced abruptly into isolation . . . Perhaps as a consequence of being thrust onto their own resources, composers during this period extended their musical languages beyond all previous limits.”

Preview Excerpts

ALFREDO CASELLA (1883-1947)

Sonatina, Op. 28

KAROL SZYMANOWSKI (1882-1937)

Masques, Op. 34

ALFREDO CASELLA

Nove Pezzi, Op. 24

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletCasella and Szymanowski: The Spread of Musical Modernism

Notes by Anne Shreffler - Professor of Music, Universiy of Chicago

The pairing of the Italian composer Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) and the Polish Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) is not as unlikely as it might seem at first glance. Both absorbed the cosmopolitan influences of pre-World War I Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, and correspondingly were at first thoroughly committed to an international modernism. Both were active in promoting the new music of the day n their own countries, later to become ardent patriots who absorved and helped to redefine the musical heritage of their respectivelands. Both Casella and Saymanowski, like Stravinsky, Berg, Webern, and Bartok, were born in the early 1880s, and came to maturity just before the First World War. The relatively stable social and political situation befor the war enabled a whole generation to spend its formative years in an environment highly conducive to cross-fertilization and interaction among artists and patrons. Once the war started, most were forced abruptly into isolation. Paradoxically, this time of unprecedented destruction produced Stravinsky’s Les Noces and LHistoire du Soldat, Webern’s Trakl songs, Satie’s Parade, Ives’s Concord Sonata, Schoenberg’s Jacobsleiter, and Berg’s Wozzeck, some of the most individual and forward-looking works of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a consequence of being thrust onto their own resources, composers during this period extended their musical languages beyond all previous limits.

With his Nove Pezzi (Nine Pieces), Op. 24 (1914), and the Sonatina, Op. 28 (1916), Casella plunged into a kind of avant-garde experimentation characteristic of so many during the war years. Both pieces exhibit extremely dense textures leading to the edge of atonality; their advanced musical language is shared by Casella’s contemporaneous Pagine de Guerra, Op. 25 (1915) and the Elegia eroica, Op. 29 (1916), both explicitly indended as responses to the war. The compositions from 1914 through 1918 display an individuality and imagination that Casella was not to equal later. After 1920, he retreated to a brittle and constructivist neo-classicism, and in the 1930s, he was to entertain more than a mild flirtation with facism, most notable in his 1937 opera Il deserto tentato, written in homage to Mussolini.

In spite of an uneven career, Casella as a composer, pianist, conductor, and organizer was one of the most important figures in Italian music before 1945. From his youth a precocious pianist, he served for many years as professor of piano at the Liceo de Santa Cecilia in Rome. He had spent the previous twenty years in Paris; at the Conservatoire, he took first prize in piano and attended Faure’s composition class. In France, Casella was able to hear the most recent works of Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and Bartok, all of whom had a major impact on Casella’s increasingly individual style. in 1915, at the age of thirty-two, Casella returned to Italy with a mission: to expose the somewhat reluctant, opera-infatuated Italian public to the new music of Europe. To this end, Casella, with his colleagues Malipiero, Pizzetti, Respighi, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco, founded the Societa Italiana di Musica Moderna, which was dedicated to performing their own works as well as the latest new music from Fance and Germany. Casella and Malipiero later formed another group, the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche, which toured Italy with Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Stravinsky’s Les Noces.

Casella’s Sonatina for piano has three movements: Allegro con Spirito, Minuetto, and Finale. The first movement is notable for its extreme density; block chords of up to nine voices permeate the texture. The non-developmental form of the movement is also striking. Instead of tying the piece together by linear of motivic progression, Casella explores the juxtaposition of two practically opposite musical ideas without attempting to reconcile them. The first idea — it appears in too many guises to be called a “theme” — is a driving, staccato figure in a readily graspable dotted rhythm. The figure does not center around any one tonic, but instead is built on successive notes of the diminished seventh chord C-Eb-F#-A, which is often reduced to a pedal C-F# in the bass. The second idea, massive vertical sonorities built up of fourths and tritones, contrasts with the rhythmically driving first idea as if it were taken from another piece. Marked Ad libitum. Appassionato e rubato assai, con molto fantasia and notated without bar lines, these interludes proceed freely, with the many indications for accelerando, ritardando, and stringendo disguising any underlying meter. A sardonic Minuetto follows, which first sets up, then undermines one’s expectations of minuet rhythm and meter. The virtuoso finale, marked Veloce molto, owes much to Stravinsky, particularly to the vein of grotesquerie found in Petroushka. The rapid figuration, based on the C# pentatonic scale, is interrupted once for a literal restatement of the ad libitum idea from the first movement. Near the end, the tempo slows to Tempos di marcia grave e solenme; according to the composer, this passage is meant to evoke the tragic Chinese march in Act II, Scene 2 of Carlo Gozzi’s play, Turandot. The work ends with a dense chordal gesture spanning almost the whole range of the piano.

Casella’s Nove Pezzi, Op.24 almost form an anthology of the techniques considered advanced in 1914. Each of the “Nine Pieces” carries a dedication; Nos. 3 and 9 were diedicated to Italian composers who were friends and contemporaries, Ildebrando Pizzetti and Francesco Malipiero, respectively. In several of the pieces, the neo-primitivism of Bartok’s Allegro Barbaro and Stravinsky’s Sacre du printemps is evident; Nos. 2 and 9, appropriately titled “In Modo Barbaro” and “In Modo Rustico,” feature powerfully rhythmic ostinatos and brief, narrow-ranged melodies. Other pieces offer wry transformations of dance rhythms, most notably the longest piece in the set, No. 8 (“In Modo di Tango”). No. 6 (“In Modo di Nenia”), dedicated to Ravel, is a quiet, contemplative Berceuse with a modal flavor. The tour de force of the set, though, is the first piece. Dedicated to Stravinsky, and entitled “In Modo Funebre,” the work avoids the parodistic tendencies of some of the other movements and confronts the problem of atonality head on. Here the texture is so dense that the pianist is often required to read four staves; yet the high level of dissonance is controlled by an extraordinary control of rhythm and phrase direction. Casella wrote later, “But if my old and firm Latin instincts preserved me from the extremes of the Viennese composers, I can still frankly admit that for several years I regarded atonality as a natural and inevitable outcome of the whole evolution of music.”1

Like Casella, Szymanowski had just returned to his homeland after years of living abroad as he began to write his most experimental music. For Szymanowski, travels outside Europe, to Algiers, Constantine, Tunis, and other “exotic” places were a means to shake off the mantle of German influence imparted to him both from training and early predilection. In a 1922 article entitled “My Splendid Isolation,” Szymanowski wrote: “I am aware that it is difficult to rid oneself of a vlued foreitn treasure, but one must do so if one is to discover one’s own jewels.”2 His studies of Arabic and ancient Western cultures provided the inspiraiton for several compositions from these years, including the Symphony No. 3 (1914-16), based on Arabic poems and the Myths for violin and piano (1915), which illustrate scened from Greek mythology.

In the solitude forced upon him by the war, Szymanowski read widely in addition to composing in a steady stream. Each of the three pieces in Masques (1916) — Sheherazade, Tantris le Bouffon, and Serenade de Don Juan — has a literary model, but are not simply loose impressions from literature. Rather, they seem clearly-drawn musical depictions of characters, lending them specific identities just as a mask would an actor. The first (and longest), Sheherazade, initially evokes the langourous beauty of the Sultan’s storyteller in sonorities reminiscent of Debussy. Contrasting episodes, each built on the continuous transformation of small motivic cells, depiect the various tales related by the narrator of the thousand and one tales of the Arabian Nights. A sense of key, though quite clear in some passages, is equally often obscured; instead, pedal points, often centered around A, repeat insistently and unobtrusively, with an Oriental inevitability. The second piece, Tantris le Bouffon, is based on Ernst Hardt’s 1906 Tristan parody, Tantris der Narr. In the play, the Tristan character never appears as himself, but uses two identites (or masks), one of which is “the strange [or foreign] fool” (der fremde Narr). Szymanowski writes a further parody of the favorite Romantic love story by interrupting moments of great lyricism with passages of almost ribald burlesque. Szymanowski dedicated the third piece, Serenade de Don Juan, to his close friend, the pianist Artur Rubinstein. The Serenade begins with a long, unbarred cadenza representing Don Juan playing under a lady’s window. As if inspired by its opening, the piece itself unfolds in improvisatory fashion, as though the Don were making occassional digressions during his serenade to remenisce about past exploits. Fragments of the original serenade music recur between more metrically organized episodes; the result is an elaborate and virtuosic tone poem for piano.

– Anne Shreffler

Professor of Music, Universiy of Chicago

1 Jim Samson, Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality 1900-1920 (New York: Norton, 1977), 77.

2 Karol Symanowski and Jan Smeterlin: Correspondence and Essays, trans., ed, and annotated by B.M. Maciejewski and Felix Aprahamian (London: Allegro Press, n.d.), 93.

Album Details

Total Time: 61:17

Recorded: June 30 – July 2, 1990 at WFMT, Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: The Armored Train (Gino Severini (1915). © ARS NY/ADAGP

Notes: Anne Shreffler

© 1991 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 003