| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

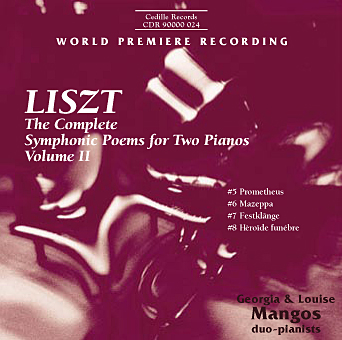

Liszt: The Complete Symphonic Poems for Two Pianos – Vol. II

This is the second volume in our historic collection of Liszt’s own two-piano versions of his 12 symphonic poems from the Weimar period (1848-61). The 3-disc series comprises the first complete recording of these works, most of which had disappeared from the repertoire by the turn of the century.

In the CD booklet, prize-winning author Alan Walker argues that the duo-piano versions are as original, as close to the underlying musical concept, as the orchestral arrangements and “quite capable of leading an independent life.” He summons Busoni for expert testimony: “Notation itself is the transcription of an abstract idea . . . From this first transcription to the second is a short and comparatively unimportant step. Yet, in general, people only make a fuss about the second.” Moreover, Liszt himself regarded the two-piano versions of the symphonic poems as independent concert pieces.

The Mangos sisters have been performing the Liszt in concert with gratifying results. “These works really have the ability to ignite an audience,” Louise Mangos says. “It’s unusual to get a robust, standing ovation for music that hasn’t been heard in 125 years. But audiences respond to these works as if they were familiar favorites.” The Chicago-area concert pianists and music professors discovered the scores, which have never been published in modern versions, while scouting for duo-piano repertoire in European libraries, collections, and music shops.

When Volume I was released in 1993, the Chicago Sun-Times called the piano version “more compelling than the orchestral ones.” American Record Guide agreed, saying the Mangos sisters “make a good case” for the music.

The sisters seem telepathically in sync with each other at the keyboards — Audio magazine noted their “absolutely perfect coordination.” Their musical kinship reflects their close personal relationship. Both were born in St. Charles, Illinois (four years apart), and have been performing together since 1981. They graduated from the New England Conservatory and studied with Paul Badura-Skoda and Joerg Demus at Munich’s Hochschule for Musik, as well as with Earl Wild at the University of Ohio. When not concertizing in the US, Canada, and Europe or scouting for forgotten piano scores, they teach applied piano and chamber music at Elmhurst College, Elmhurst, Illinois. The second generation Greek-American sister — each is married to a Greek-American architect — live about a block apart.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

Artists

1: The Symphonic Poems for Orchestra of Franz Liszt as Transcribed for Two Pianos by the Composer*

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLiszt's Symphonic Poems, Vol. II

Notes by Alan Walker

Pianists have scarcely begun to realize what a vast treasury of music lies buried in Liszt’s arrangements for two pianos. This repertory is one of the major discoveries of the ongoing “Liszt revival”. A glance at the composer’s Complete Catalogue reveals the stunning figure of twenty-six pieces in this genre — more than that of any other composer of the Romantic Era. Why are they so rarely performed? Perhaps the word “arrangement” itself is partly to blame for the mantle of neglect that has fallen on these beautiful compositions. Was not the piano the workhorse of the Romantic Age? And were not piano arrangements the means par excellence whereby our forefathers got to know orchestral music and operas? At best, this was a humdrum, utilitarian repertory. If the gramophone record had been available, so the argument runs, Liszt would hardly have wasted his time re-writing everything for four hands.

This notion of the piano arrangement as the “gramophone record” of the nineteenth-century was always false. The gramophone has meanwhile been invented, so why are Liszt’s arrangements now being recorded? A strange reversal of logic! The reason has to do with the quality of the arrangements. They are profound examples of the re-creative process at work (not hack transfers from one medium to another) and they are quite capable of leading an independent life. It is almost as if these symphonic poems exist in at least two forms, both of them original. (The idea is not far-fetched: Liszt very often worked on the orchestral and two-piano versions simultaneously. Sometimes we simply do not know which version came first.) They put the very term “arrangement” to shame. It is a pathetic label and we would happily dispense with it, especially with Liszt. His arrangements are executed with such brilliance that they often eclipse the model that gave them birth. His piano transcriptions of Chopin’s songs, for example, are in every way superior, and sound like original keyboard compositions.

And there is something else, too. For Liszt a composition was rarely finished. It can sometimes exist quite happily in several versions, not one of which is more “definitive” than the others. If proof of this radical idea be required, we need look no further than Mazeppa. It exists in at least six different versions (four for solo piano, one for orchestra, and one for two pianos). Which is the original? Is it possible that they are all arrangements, all versions of an Ur-composition which lies deep in the background, forever unexpressed?

Both Busoni and Schoenberg held the rather beautiful notion that music is quite separate from its utterance — that is, separate from the medium through which it speaks. The idea is pure, ideal, as yet unarticulated, even by the sound it needs must possess before it can communicate with the listener at all. “Notation itself is the transcription of an abstract idea,” wrote Busoni. “The moment the pen takes possession of it, the thought loses its original form.” And he concludes: “From this first transcription to the second is a short, and comparatively unimportant step. Yet, in general, people only make a fuss about the second.”

Liszt’s unique approach to two-piano arrangements is revealed in his transcription of Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto, which, while it is not on this disc, reveals a truth about everything that is. All the “hack” arrangers keep Beethoven’s solo piano as he wrote it, while the orchestral accompaniment is relegated to the second piano. Not so Liszt. The textures of both the solo and orchestral music are shared between two keyboards. The result is an acoustical revelation.

II

Nowhere is Liszt’s theoretical picture of music more clearly revealed than in his symphonic poems. He believed that music could be “fertilized” by the other arts, painting and poetry in particular. He popularized the idea of “programme music” and so began a controversy that still goes on today. What kind of an art is music? Is it a closed world, a thing-in-itself, remote from everyday existence? Or is it connected to the experiences of life, and does it possess the mysterious power to express them? These contrasting viewpoints agitated the world of nineteenth-century music and led to “The War of the Romantics”. On one side of the battle lines stood Mendelssohn, Brahms, Schumann and Bruckner; they regarded music as “abstract”. On the other stood Liszt, Wagner and the young Richard Strauss who saw it as “representational”, a word that requires some definition. Liszt did not mean that music can depict a flower, a picture, a poem, or a storm. Such things are mere externals, and music demeans itself if it attempts to imitate them. What it does is more subtle. It expresses the mood that such things evoke in the heart and mind of the observer, and transmutes it into musical experience. Liszt’s manifesto on the topic appears in the Preface to his Symphonic Poems.

It is obvious that things which can appear only objectively to perception can in no way furnish connecting points to music; the poorest of apprentice landscape painters could give with a few chalk strokes a much more faithful picture than a musician operating with all the resources of the best orchestras. But if these same things are subjected to dreaming, to contemplation, to emotional uplift, have they not a kinship with music, and should not music be able to translate them into its mysterious language?

In brief, whenever Liszt attaches such titles as “Hamlet”, “Prometheus”, or “Mazeppa” to his compositions he is revealing his sources of inspiration, not providing the listener with a literary or pictorial blueprint.

When Liszt decided to abandon his life as a traveling virtuoso, in 1847, he was only thirty-five years old. He settled in the sleepy German town of Weimar, where he became Kapellmeister to the Grand Duke Carl Alexander. His chief desire was to find more leisure to compose. Hitherto he had written mainly piano music. An orchestra was now placed at his disposal, and he was able to carry out many experiments in the theater that had been impossible for him during his earlier years as a wandering minstrel. Liszt published twelve of his thirteen Symphonic Poems during his Weimar years (1848-61). The term “symphonic poem” was invented by Liszt. It describes a genre that was strikingly original for its time: he rolls the four contrasting movements of the classical symphony into one, and generates the contrasting ideas from a small handful of basic motifs through the “metamorphosis of themes” technique. It will not escape attention that a number of these works deal with exceptional heroes — Mazeppa, Prometheus, Hamlet, Orpheus — characters who face overwhelming odds or find themselves in an impossible dilemma. Liszt readily identified with their struggle and did some of his best work in their company, so to speak.

III

Prometheus was first performed on the occasion of the unveiling of the Herder statue in Weimar, in 1850. Five years later Liszt revised the score. The piece symbolizes the Greek legend of Prometheus who stole fire from Heaven and gave it to Mankind. For this crime he was chained to a rock by the gods who caused his liver to be torn out by vultures — a punishment from which he was delivered by Hercules. This graphic story is projected by means of violent harmonies and turbulent textures which place the work well ahead of its time.

Mazeppa is an expanded version of the fourth of the Transcendental Etudes. Victor Hugo’s poem describes how Mazeppa, a Cossack chieftain born in 1644, was captured by his enemies and sentenced to be bound naked to the back of a wild horse. The animal is released and streaks over the hills and plains and returns to its native Ukraine. There Mazeppa, all but dead, is rescued by peasants whom he eventually leads against his foes. Liszt’s music captures the frenzy of the gallop as it begins with a whiplash of a chord and pounds toward its unknown destination.

Festklänge was composed in 1853 in anticipation of Liszt’s wedding to Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein. The marriage never took place because the long fight to secure an annulment of her first marriage ran into legal problems that were not resolved for another eight years. The presence of a Polonaise in the middle section is meant to symbolize Carolyne’s Polish origins.

Héroïde funèbre started life as the slow movement of a youthful “Revolutionary” symphony (1830) which was never finished. Nearly twenty years later, at the time of the Hungarian Uprising (1848-49), Liszt was moved to return to his early sketches and produce a massive funeral march of Mahlerian dimensions. It was not Liszt’s intention to memorialize particular heroes. Rather was it to erect a musical monument to heroes and revolutions in general. He wrote that he regarded war as “a funeral banner that floats above all times and places . . . It is for Art to throw its transfiguring veil on the tomb of the brave, to encircle the dead and the dying with its golden halo, so that they may be the envy of the living.”

That Liszt regarded the two-piano versions of the symphonic poems as independent concert pieces cannot be doubted. For many years he was the President of the Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein and regularly attended the annual festivals held all over Germany. His two-piano arrangements were often featured in the programmes, even though a full symphony orchestra was available to play them. And they were regularly included in the concerts of his friends and pupils. In June 1882, for example, his students Richard Burmeister and Dori Petersen played Festklänge and Les Préludes in public concerts in Weimar. Three years later, in June 1885, August Stradal and August Göllerich played Héroïde funèbre to Liszt’s masterclass in that same city. (“Make the rhythmic accompaniment rumbling and heavy,” Liszt told them on that occasion. And, at the second appearance of the theme: “Almost always with the pedal, scarcely ever release the pedal.”)

Liszt took a fatherly interest in the fate of these pieces, as his comments indicate, and sometimes even presided at one of the keyboards himself. Even the Leipzig Gewandhaus (for long a seat of opposition to Liszt and his music) was once treated to a memorable performance of Liszt’s orchestral masterpiece, A Faust Symphony, played on two pianos by Arthur Friedheim and Alexander Siloti in Liszt’s presence, complete with male-voice chorus and tenor soloist. With Liszt’s death, in 1886, however, these arrangements fell into neglect. The dreary period of anti-Romanticism that followed did the rest. A unique repertory was hushed up and forgotten. Only now are we starting to penetrate the conspiracy of silence in which these compositions have for so long been wrapped. This is music which demands attention.

Prize-winning author ALAN WALKER was born in England. He broadcasts regularly for the BBC (London) and for public radio in North America; he also gives frequent lectures on the music of the Romantic Era, a topic in which he specializes. The first volume of his ongoing biography of Franz Liszt (“The Virtuoso Years”) was published in 1983, and gained two international prizes: the James Tait Black Award for the best biography of the year and the Yorkshire Post Music Book Award for the “Music book of the Year”. For the second volume (“The Weimar Years”) Alan Walker received the Liszt Medal. In 1995 the Government of Hungary bestowed on him one of its highest cultural decorations, the medal Pro Cultura Hungarica.

Album Details

Total Time: 59:00

Recorded: June 12, 14, & 16, 1995 in Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: “Two Pianos” – Glass Block Impression by Erik S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Alan Walker

© 1995 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 024