| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

Store

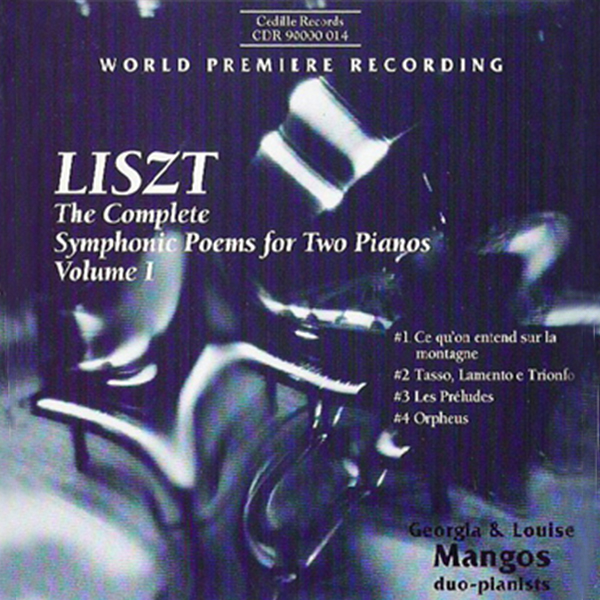

Liszt: The Complete Symphonic Poems for Two Pianos – Vol. I

This is the first volume in our historic collection of Liszt’s own two-piano versions of his 12 symphonic poems from the Weimar period (1848-61). The 3-disc series comprises the first complete recording of these works, most of which had disappeared from the repertoire by the turn of the century.

The Mangos sisters have been performing the Liszt in concert with gratifying results. “These works really have the ability to ignite an audience,” Louise Mangos says. “It’s unusual to get a robust, standing ovation for music that hasn’t been heard in 125 years. But audiences respond to these works as if they were familiar favorites.” The Chicago-area concert pianists and music professors discovered the scores, which have never been published in modern versions, while scouting for duo-piano repertoire in European libraries, collections, and music shops.

“In comparing the two-piano versions of the Symphonic Poems to the orchestral scores,” write the Mangos sisters in their program notes, “one finds many similarities in Liszt’s approaches to the two mediums. Liszt strove to expand the repertoire of sounds for all the instruments of the orchestra as well as for the piano, creating new sound textures for both by broadening their dynamic range and expoiting extreme registers of pitch to an unprecedented degree. The feature that most unifies the two mediums is the force and brilliance of Liszt’s virtuosic writing, which makes the two pianos sound truly orchestral in timbre.

“Ultimately, however, we fell that the flexibility of two players, as opposed to a full orchestra of about seventy musicians, adds an extra dimension to the two-piano transcriptions that makes them superior listening experience. They sound more vital because they can be played with abandon. The nuance of tempo, volume, and texture is so agile between two players that it begins to take on the quality of spontaneous virtuoso improvisation. (One must remember that Liszt saw virtuosity as a means of heightening dramatic content, not as mere technical exploitation.)

“Finally, we hope this recording awakens the grand Lisztian spirit within all of us.” (Georgia & Louise Mangos)

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDiscovering Liszt's Symphonic Poems

Notes by Georgia & Louise Mangos

After playing so much of the “standard literature” for two pianos, we found ourselves thirsting for something fresh to learn and perform. We therefore became musical sleuths seeking out-of-print scores. Although our calculated guesses as to where to find such scores were not always successful, we eventually became quite adept at our scholarly endeavors. It was always our dream to find a major work by a major composer that had, for whatever reason, been left to obscurity. Our travels in search of such a unique find took us to libraries, museums, universities, and even antique music stores throughout Europe and the United States.

Our diligence has been greatly rewarded, for Liszt’s own two-piano transcriptions of his Twelve Symphonic Poems represents a huge historic and artistic find. This collection, although well known in its orchestral versions, has drifted into obscurity even among Liszt scholars. The discovery of the scores was thrilling enough, but the process of learning and sharing with the listening public works of such artistic stature has been miraculous. As the only modern performers (so far) of these pieces, we have come to know and live with them in a most unique and personal way. We hope the rest of our observations will aid the listener in his or her own discovery of these fascinating works.

The most significant problem Liszt’s Symphonic Poems have presented for listeners and critics is their highly segmented structure. Although many will at first find this a weakness, it in fact becomes a strength. Liszt’s method of presenting new themes and developmental ideas is rhapsodic: separating passages from one another with numerous tempo, mood, and key changes. These disparate segments eventually begin to feel like the chapters of a book. While there is the feeling of concluding a thought at the end of each chapter, the reader (or listener) knows the story is not yet finished. Just as a good author compels the reader to turn the page and discover what happens next, Liszt propels the listener into the next facet of his journey.

This complete freedom of form is startling. Our Germanic classical ears feel most comfortable with traditional structures like sonata form. That Liszt takes the listener on a dramatic journey that does not depend on themes reoccurring in familiar keys is quite alarming at first. In fact, it can feel totally unruly. As one comes to appreciate the temperament of the writing, however, one realizes that the intellectual aspects of structure are not Liszt’s dominant concern. Instead, Liszt lets the emotional and dramatic story line dictate the form. Each note is written with an expressive purpose in mind, and each Symphonic Poem has a unique design.

The concept of the “Symphonic Poem” (a term Liszt coined) carries no set rules. It is the trip into Liszt’s imagination and soul that makes these pieces so convincing. The pianist does not even have to take the literary influences too literally: the texts on which the Symphonic Poems are based did not entirely dictate Liszt’s writing, so why should we let them inhibit what we come to believe as the pieces’ true meanings? As pianists, we must feel free to interpret and apply our own musical imaginations to Liszt’s scores, just as he applied his genius to the texts before him.

Liszt is a master story teller, and it is up to us to travel this journey with him. On a very simplistic level, Liszt’s Symphonic Poem cycle is similar to Schubert’s song cycle Die schöne Mullerin. In both, the listener is taken through the emotional, spiritual, and physical life of a male protagonist as both composers reflect on the insecurities of human nature. However, Schubert presents his miller as a mere mortal resigned to accept his fears and limitations. Liszt, on the other hand, makes us feel that man’s divine energy allows him to conquer his fears, reach great heights, and at times even rival the gods of mythology that appear throughout these works.

The recurring themes in these pieces are Man against the mythological gods, Man against nature, and Man against Man as in war. All are beautifully portrayed in the music. However, it is Liszt’s exploration of the emotional conflicts within man that makes these works so provocative. Man’s need to rely on God for spiritual enlightenment is continually felt in these pieces, expressed through poignant hymns of truly divine simplicity. Man’s fear of being alone and losing a loved one is depicted in Orpheus, while our fear of death is probed in Tasso. Man’s mortality was one idea with which Liszt did not cope well, preferring to ignore human mortality by allowing a man’s work to elevate him to the immortal. Following are brief commentaries on the first four Symphonic Poems, which appear on this recording.

Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne (What One Hears on the Mountain Top) takes its name from a poem by Victor Hugo. Liszt, however, adds his own interpretation by way of program. The aesthetic dynamic of the work rests on a central dichotomy where the voice of nature is juxtaposed with that of humanity. A chorale, marked Andante religioso, appears in the middle and again at the end of the symphonic poem. Expressing “consecrated contemplation” according to Liszt, this chorale appears to show Man resolving his conflict with nature through the strength and wisdom that he receives from God.

Tasso, Lamento e Trionfo was originally composed as an overture to the Goethe play Torquato Tasso. Liszt describes Tasso as “The genius who is misunderstood by his contemporaries and surrounded with a radiant halo of posterity” (much the way Liszt saw himself). The thematic economy and motivic transformations in Tasso serve to support the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis pattern common to many of Liszt’s large-scale works. The music presents three distinct ideas: Tasso in death, his great spirit hovering around the lagoons of Venice; Tasso at the court of Ferrara (the minuet middle section); and Tasso in culture: an apotheosis celebrating Tasso as martyr and poet as the suffering artist transcends the constraints of the physical dimension to achieve immortality.

The success of Les Préludes, Liszt’s best known symphonic poem, is due in large part to its economical use of motivic material, the beauty of its cantilena melodies, and the brilliance of its storm and stress writing. Once again the musical program is one of juxtaposition and apotheosis, revealing a three-part archetypal pattern reflecting the human condition: from birth, consciousness, and innocent love; to hardship and disillusionment; to consolation, decision, and transcendence.

Orpheus is the most pictorial of the Symphonic Poems. The two-piano version opens with the pianos imitating the sounds of Orpheus’s lyre (sounds created by two harps in the orchestral score). The chorale section that follows depicts the spiritual beauty of art. The strumming sounds of the harp return with a beautiful single vocal line floating above the accompaniment. Liszt transforms this serenade into an impassioned love theme by doubling the melody in octaves as it soars over the sounds of the harp and full chordal orchestral accompaniment. The descending octave passages that follow can be heard as Orpheus’s laments over his beloved Eurydice’s death, while rumbling octaves in the bass bring forth the images of the Underworld. The work closes with a spectacular use of the echo effect: as each chord is repeated at a lesser volume one feels the spirit of Eurydice slipping inexorably away from her lover.

Liszt is such a great story teller because of the strength of his characters and the vibrancy of the conflicts he creates within them. The vivid images he creates through sound become like the characters of a brilliant novel. The pianists are therefore not merely musical performers in these tales. We become actors playing each and every character from the brave warrior, to the pious supplicant, to Mother Nature. We can possess the strength of a Greek God in one instant, and be dancing a waltz in the next. What a wonderful role we get to play!

In comparing the two-piano versions of the Symphonic Poems to the orchestral scores, one finds many similarities in Liszt’s approaches to the two mediums. Liszt strove to expand the repertoire of sounds for all the instruments of the orchestra as well as for the piano, creating new sound textures for both by broadening their dynamic range and exploiting extreme registers of pitch to an unprecedented degree. The feature that most unifies the two mediums is the force and brilliance of Liszt’s virtuosic writing, which makes the two pianos sound truly orchestral in timbre.

Ultimately, however, we feel that the flexibility of two players, as opposed to a full orchestra of about seventy musicians, adds an extra dimension to the two-piano transcriptions that makes them a superior listening experience. They sound more vital because they can be played with abandon. The nuance of tempo, volume, and texture is so agile between two players that it begins to take on the quality of spontaneous virtuoso improvisation. (One must remember that Liszt saw virtuosity as a means of heightening dramatic content, not as mere technical exploitation.)

Finally, we hope this recording awakens the grand Lisztian spirit within all of us.

Album Details

Total Time: 66:32

Recorded: January 22, 23, 1993 in Lund Auditorium. Rosary College, River Forest, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: “Two Pianos” – Glass Block Impression by Erik S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Keith T. Johns; Georgia & Louise Mangos

© 1993 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 014