| Subtotal | $12.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.23 |

| Total | $13.23 |

Store

Store

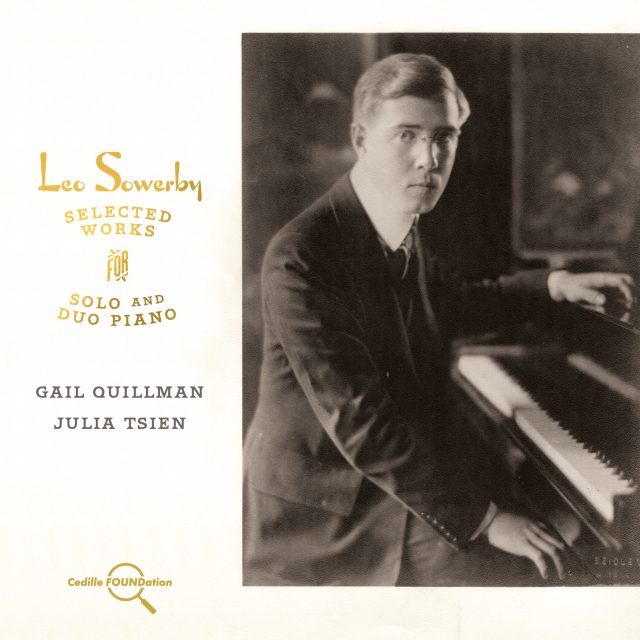

Leo Sowerby: Selected Works for Solo & Duo Piano

This album of world-premiere recordings features solo and duo piano music spanning nearly the entire career of Prix de Rome and Pulitzer Prize winning composer Leo Sowerby (1895–1968), one of the most distinctive American voices of the early and mid-20th century. Recorded in 1997 in Chicago, where Sowerby spent the bulk of his student and professional life, the album is being released at mid-price on the Cedille FOUNDation line. Pianists Gail Quillman and Julia Tsien share a direct musical lineage to Sowerby. Quillman, who established the Leo Sowerby Foundation, studied with Sowerby, and has performed more of his solo piano and chamber music than anyone else. Tsien, an active performer and teacher, was a Quillman student.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Francis Crociata on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

LEO SOWERBY (1895–1968)

Three Summer Beach Sketches, H109

Suite for Piano — Four Hands H371

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLeo Sowerby: Selected Works for Solo & Duo Piano

Notes by Francis Crociata

Allow me to begin with one amazing, albeit stark fact. Not a single work in this collection was published in Sowerby’s lifetime, and only two, Fisherman’s Tune in its solo version, and Three Summer Beach Sketches in a 1995 Sowerby Foundation Edition, are in print today.

The last wave of European composer-pianists — Paderewski, Hofmann, Rachmaninoff, Grainger, Prokofiev and Bartok—was just beginning to touch American shores when a home-grown red-headed prodigy of our own was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan on the first day of May, 1895. So it’s not so surprising that Dr. Leo Sowerby, who achieved fame as a symphonist, composer-organist and church musician, initially set out as “Master Leo Sowerby—the Wonderful Boy Pianist—Only 10 Years Old!” hoping to model himself after musicians who themselves aspired to be the successors of Liszt, Rubinstein, Chopin, Mendelssohn and Beethoven.

The aspiring wunderkind composer-pianist made a good start by seeming to toss-off knuckle- and thumb nail-busters like Liszt’s Don Juan Fantasy and Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata. A year later, at age 11, he ventured to include the first known work of his own, now lost, entitled The Dawn of Day. The Dawn of Day was the first of one of the most imposing bodies of music ever produced from the creative imagination of an American composer—550 works in every form but opera—a catalogue that prompted even a lifelong Sowerby-devotee, the Washington Post critic Paul Hume to exclaim in exasperation “Good Lord, there are five lifetimes of music here!” Along the way, Sowerby wrote an even larger body of organ works, seven symphonies (five orchestral, a massive Psalm Symphony, and a jazz symphony based on the Sinclair Lewis novel Babbit), seven concerted works for organ, three for piano, a dozen tone-poems and overtures, countless instrumental sonatas, secular and sacred songs and over two-hundred anthems and cantatas. He was, from about 1915 (the time of Three Summer Beach Sketches, the first work on this program) the Chicago Symphony Music Director Frederick Stock’s “fair-haired boy,” in effect the Chicago Symphony’s composer-in-residence. He received the first American Prix de Rome, the fourth Pulitzer Prize, was profiled in Time magazine and, for the last six years of his life, founded and directed the College of Church Musicians at Washington National Cathedral.

Leo Sowerby’s career as a pianist lasted until 1927, his 37th year of life and the year he began his 35-year tenure as organist-choirmaster of Chicago’s St. James Episcopal Church (later Cathedral). That year he played his final concerto performances in Chicago—his own First Piano Concerto and, with Ernst von Dohnanyi and Felix Borovsky, the Bach Triple Concerto. That summer he played his final piano recital at his beloved summer retreat at Palisades Park, Michigan. (The printed program concluded with the signature work of another Chicago composer-pianist, Zev Confrey’s Kitten on the Keys.)

Elsewhere I have written that Sowerby’s public life was divided into two periods, his first act one of high celebrity and performers and ensembles ready to play whatever he wrote. His second act, which ironically began about the time he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1946, saw him remain among the most frequently performed composers of organ and choral works, while the concert-world-at-large mostly ignored him. Even the home team, the Chicago Symphony, virtually abandoned him after Stock’s death. If it weren’t for Sowerby’s ever-faithful friend and champion, the English concert organist E. Power Biggs, Sowerby wouldn’t have been played at all in the 1950s and 60s with the orchestras of Chicago, Detroit, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Philadelphia.

That was how the world looked at Sowerby, but not how Sowerby looked at the world. He simply kept writing, irrespective of the fame it brought him or didn’t, and if big names no longer sought him out (the violist William Primrose seems to have been the last to do so, though the manuscript of his Second Violin Sonata turned up in Jascha Heifetz’s estate), he wrote for his colleagues at Chicago’s American Conservatory, players in the Chicago Symphony and former students, for example, the pianist Gail Quillman, who studied harmony and counterpoint with Sowerby in the mid-1950 and remained devoted to her teacher’s music and his memory right up until the present day.

Gail and her former student Julia Tsien have recorded a generous selection of his sixty-four piano works, including all of Sowerby’s four-hands pieces excepting an four-hand arrangement of an early tone poem The Sorrow of Mydith and the Ballade for Two Pianos and Orchestra (“King Estmere”), once the most often-played Sowerby orchestral work. This was thanks to a now-forgotten duo-piano team, Guy Meier and Lee Pattison. King Estmere was their signature piece. They toured it with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra and played it with every major North American orchestra extant in the 1920s and 30s. Meier and Pattison split-up in 1930 and again in 1933, so other than a single performance in 1936 at Howard Hanson’s American Music Festival, the Ballade, as audience-friendly and virtuosic a piece as Leo ever wrote, wound up on a closet shelf until Quillman and Tsien revived it during the Sowerby centennial year of 1995.

Because all of this music has been unperformed for anywhere from fifty to one hundred years and spans virtually Sowerby’s entire maturity, 1915 to 1959, hearing them all at once leaves several conflicting impressions. The first is that the earliest work, Three Summer Beach Sketches is the most adventurous harmonically. In 1915, the twenty-year-old Sowerby began a short period as an occasional student of the Australian composer-pianist Percy Grainger. Although ostensibly piano lessons, according to Sowerby, these were really just repertory bull sessions with Grainger and Sowerby playing for each other their own music, plus other composers’ works they most admired. Sowerby offered works by Bach, Franck, Mendelssohn, Debussy, and Ravel. From Grainger, Sowerby heard and came away with a lifelong passion for the music of Grainger’s friend Frederick Delius.

The first bit of evidence of those Grainger “lessons” is discernible before you hear a note of the Beach Sketches. Dropping traditional Italian tempo and dynamic indications, Sowerby, for the remainder of his life, adopted Grainger’s practice of employing highly descriptive performance directions in English such as “Merrily with snap,” “Boldly,” “With intensity of expression,” “To be played with verve,” etc. For Sketches, the pianist is presented with “in big style,” “introspectively,” and “solemnly” — with no metronome markings and, in the third movement, no bar lines. (After all, 1915 was just two years past the premiere of The Rite of Spring!) The outer movements are big, virtuosic etudes, with lots of rhythmic variety and surprising, unexpected, and sometimes quirky modulations plus, in the words of Sowerby student Ronald Stalford, “chords you’d never encounter in a score not having the name Sowerby at the top of the page.” The inner movement is especially surprising as one of the earliest serious compositions to use jazz and blues harmonies.

Sowerby composed his 1959 Suite for Piano — Four Hands, and Beach Sketches at his summer cottage retreat — a cabin, really — in Palisades Park, Michigan. As with the Sketches and most of Leo’s music in general, he included no metronome markings; in this case, he even left the movement order up to the performers. Each of three performances at which Sowerby’s attendance has been documented used a different order. Quillman and Tsien have taken this principle of experimentation two steps further by playing the work in yet a different order — and on two pianos. To my ears, the Suite is more in keeping with Sowerby’s style in the 1940s than the late 1950s — and in the two introspective movements, even earlier than that. I would like to offer three clues as to the influences that touched Sowerby in the composition of the Suite; about one of which I am certain, the other two are educated guesses. Two are kinships with composers Sowerby liked and had assisted along the way: Samuel Barber, for whose Prix de Rome Sowerby had advocated (the Fugue is unmistakably reminiscent of Barber’s Piano Sonata, which Leo used regularly in teaching counterpoint) and his own former student Ned Rorem — echoes of his early Toccata for Piano can be discerned in the rollicking movement marked “Fast and glittering.” Sowerby’s former student William Ferris attests to another inspiration in that movement. In the late 1950s, with his friend “Jimmy” Biggs and the San Francisco Symphony, Sowerby conducted the west coast premiere of Poulenc’s Concerto for

Organ, Strings and Timpani along with one of the three concertos he’d written for Biggs. Leo loved San Francisco and, being a lifelong rail-enthusiast, was enthralled by the city’s famous cable cars. Ferris confirms that the “Fast and glittering” movement was designed to evoke an impression of the rapidly accelerating and decelerating movement of the cars up and down the steep avenues.

Although Sowerby stopped playing piano in concert in 1927, he by no means stopped writing for the piano. The piano soloist who was his most passionate advocate in the late 1920s and early 30s was an Iowan, a student of Josef Lhevinne who Leo met at the American Conservatory: Frank Mannheimer. By the late 1920s, Mannheimer had moved to London, first to study with and then to assist the legendary pedagogue Tobias Matthay. Mannheimer scored a major success by introducing, first in Europe and then New York, Sowerby’s Florida Suite, the first of several Sowerby works to appear in handsome — and prestigious — Oxford University Press editions. Sowerby and Mannheimer followed their success with the impressionistic Florida Suite — with its echoes of a cypress swamp, pines at dusk, etc. — with the second manifestation Sowerby’s turning in the direction of formal contrapuntal structures. He had just completed what would come to be regarded (by friend and foe alike) as his masterpiece, the 1930 Symphony in G for solo Organ, which concludes with an immense, ingenious, and triumphant passacaglia. He followed in 1931 with Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue for solo piano, intending it for Mannheimer, who, unaccountably, never played it. Sowerby, equally unaccountably, never showed it to another pianist. Sowerby wrote another Passacaglia for Mannheimer in 1939, this one in a more expansive, virtuosic spirit, with some astonishing and very funny pratfalls up and down the keyboard and a coda to wake the dead that Mannheimer did perform. The present Passacaglia, however, is of a different sort than the later one that organists have ever since ridden to cheers and standing ovations. Here Sowerby weaves, in three connected movements, a dreamily reflective French impressionist take on classic forms, ending with what may well be the quietest, most sensual fugue coda ever written by an American. The piece has also enjoyed a second life. Instead of trying to find a pianist willing to end a major modern composition quietly, two years later, Sowerby Fugue to be the 12th of 17 of his works to be lifetime. Stock revived the piece in two future seasons and, ending Sowerby’s absence from CSO programs since 1946, Fritz Reiner, early in his Chicago tenure in December 1955, chose it to reintroduce Sowerby to Orchestra Hall audiences, writing to his old friend (whose From the Northland Suite he’d premiered in Cincinnati and New York), “In your case, I don’t have to wait to know who’s who and what’s what in Chicago.” (Cedille Records CDR 90000 039 includes, on an album built around Sowerby’s Symphony No 2, the world-premiere recording of the orchestral version of Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue.)

Prelude (for two pianos), composed in October 1932, almost exactly a year following Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue, continues in an introspective vein, although evincing more English austerity than French sensuality, more Delius than Debussy (calling to mind musicologist Paul Henry Lang’s description of Sowerby: “Like Delius through stained-glass.”) While there is no paper trail as to its provenance (i.e., whether it was requested or commissioned) Maier and Pattison, after abandoning their partnership in 1930, decided to try again in 1932 and may have included the Prelude in their comeback tour. They also included in their repertory the final two works on this album, Fisherman’s Tune, an elaboration of a solo piano work Sowerby had played himself, as did Percy Grainger, for whom the work was an homage. The two-piano version was introduced by Silvio Scionti, a former pupil of Liszt’s student Sgambati, and his student Stell Anderson. Scionti and Anderson gave what is the first documented performance of the Prelude in Jordan Hall, Boston, in 1935.

In 1924, three years before Sowerby announced he was abandoning his waning career as a piano soloist for that of an organist and church musician, upon his return from his three-year Rome Prize fellowship, he received an intriguing invitation from an unexpected admirer, Paul Whiteman. Whiteman’s experiment in symphonic jazz had resulted in several succès d’estime and one triumph, George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. He invited Sowerby to tour the Midwest with his orchestra, along with Gershwin, Confrey, and Ferde Grofe. He wanted his composers to interact with the musicians of his renowned jazz orchestra, each of whom was proficient on a variety of instruments. It must have been quite a tour, with Gershwin, in defiance of the prevailing 18th Amendment, converting Sowerby from Scotch to Martinis. Confrey wasn’t particular and drank whatever came to hand. Grofe couldn’t party, as he was put to the endless task of copying band parts.

The Sowerby-Whiteman collaboration produced two works, the aforesaid jazz symphony (unfortunately entitled “Monotony–Symphony for Jazz Orchestra and 6 ½ foot metronome) which, to Sowerby’s chagrin, Whiteman proclaimed in the press contained more and greater genius than all the works of Stravinsky. The first work was the overture-length sonata movement Leo titled Synconata. The work functioned well as a curtain-raiser and it’s second theme conveys a rather eerie presage of the tune of Cy Coleman’s 1966 song, “If They Could See Me Now” from broadway show Sweet Charity. Incidentally, both of Leo’s jazz works contain two-piano parts of some difficulty. In Whiteman’s first performance of Synconata, the two pianos were played by Sowerby and Confrey. Fresh on the success of the Ballade for Two Pianos and Orchestra, Maier and Pattison asked Sowerby for a recital work. We don’t know who thought of arranging Synconata, but it was a natural.

Album Details

PRODUCER Francis Crociata

ENGINEER Hudson Fair

EDITING Joseph Patrych

RECORDED Ganz Hall, Chicago Musical College of Roosevelt University, August 21–23, 1997

PUBLISHER Three Summer Beach Sketches H109 © 1995 Leo Sowerby Foundation

Recording and production funded by a grant from the Leo Sowerby Foundation.

© 2019 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 7006