| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

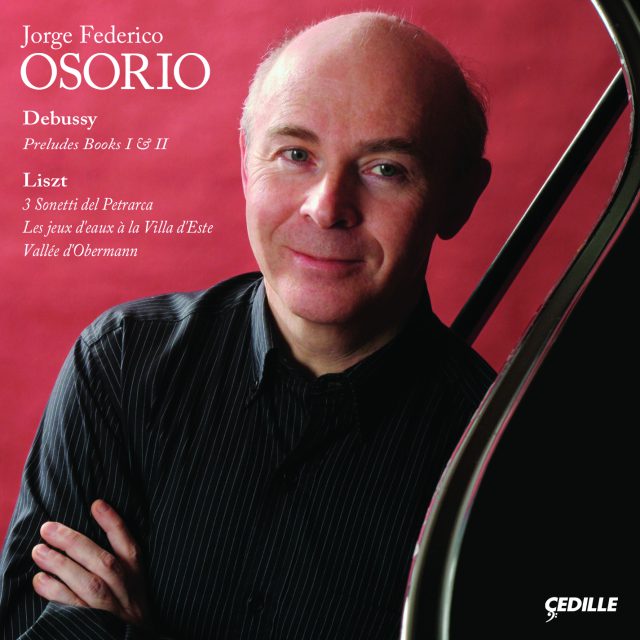

Jorge Federico Osorio: Debussy and Liszt

When pianist Jorge Federico Osorio gave a recital in New York’s Lincoln Center earlier this year, The New York Times praised his “considerable imagination for subtle timbres and vivid characterizations” in works of Debussy and his “beautifully articulated” and “explosively virtuosic” readings of Liszt.

Hear those qualities for yourself on Osorio’s new CD of Debussy’s Preludes Books I & II framed by selections from Liszt’s “Années de pèlerinage,” the 3 Sonetti del Petrarca, Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este, and Vallée d’Oberman, which show the genesis of the coloristic piano writing that Debussy took to its highest level.

“Osorio plays on a large canvas, and uses it to the fullest,” noted American Record Guide. And that’s precisely what he brings to these colorful works by piano masters who use every ounce of the instrument’s sonority.

Preview Excerpts

Sonetti del Petrarca (c.1837-49)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918)

Preludes, Book 1

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletWhat did the west wind see . . . and does it tell us anything about the music?

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

“We must agree that the beauty of a work of art will always remain a mystery, in other words we can never be absolutely sure “how it’s made.” We must at all costs preserve this magic which is peculiar to music and to which, by its nature, music is of all arts the most receptive.”

— Claude Debussy, quoted by biographer Roger Nichols

“The mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness; this power arises from within, like the colour of a flower which fades and changes as it is developed, and the conscious portions of our natures are unprophetic either of its approach or its departure.”

— Percy Bysshe Shelley ‘the Defence of Poetry’

Instrumental music of the Baroque and Classical eras can be characterized as abstract – with limited exceptions, such as Vivaldi’s descriptive “Four Seasons” violin concertos, with image-filled sonnets attached. Basically, though, Bach concerti, Haydn symphonies, and Beethoven string quartets are pieces of music that are simply about themselves. Their interest lies in the manipulation of melodies and rhythms; in the decoration, harmonization, and development of basic themes; and in key relationships and modulations. The works are not intended to have extra-musical meaning, but to be heard and appreciated strictly on their own terms.

Abstract music (or what some academic snobs have called “pure” music) did not die out with the advent of Romanticism in the 19th century, or with the proliferation of approaches that has characterized the 20th and 21st centuries. But a parallel trend emerged from the change of attitude ushered in by the Romantic movement. Romantics in all the artistic disciplines sought to discover the connections between humankind and the natural world, and between present life and the past (often an idealized past, a “golden age,” to which they longed to return). They placed prime emphasis upon emotion rather than what they saw as cold rationalism. They came to believe (with considerable justification) that all forms of art spring from similar sources and inspirations. Thus poetry, painting, sculpture, dance, music, and drama were all related. Romantic-era composers such as Schumann, Berlioz, Liszt, Mahler, and Richard Strauss were no lesser musical craftsmen than their Classical predecessors, and their works can be analyzed and understood in strictly musical terms. But they and others of their time added another dimension, another level of interest: the evocation of moods and emotions, the depiction in instrumental sonority of natural scenes and of the metaphors of poetry.

Claude Debussy, a post-Romantic, shows his skepticism of his forerunners’ ideas when he points out ‘this magic which is peculiar to music.” He recognized that, in the end, music is different from other arts. It is sound that produces meaning from itself, from the internal relationships of intervals, the movement of rhythms, and the timbre of the instruments used to play it. He appreciated, at the same time, the influence that extra-musical stimuli can have on composition: the echo of an especially evocative line of poetry, sunlight on the sea, the glow of moonlight, the special colors and shadings of a painting. Debussy knew how Schumann and Liszt had translated landscapes and legends into striking character-pieces for piano and adapted their techniques to his own style: a keyboard sound that involves more diffuse melodic patterns, more chromatic harmonies, and more complex rhythmic structures. Above all he was fascinated with the sound of the piano – its whole extended range from highest to lowest, the ways its pedals can change the quality of the tone color, the brilliance to be achieved with fast runs, the power of huge chords, all the resonance of this very powerful instrument. This fascination with piano sound seems to have inspired the creation of his two books of Preludes at least as much as any poem or picture referenced in the pieces’ individual titles. In fact, Debussy placed his preludes’ titles at the end of each piece, not the beginning, which suggests they were, to some extent at least, afterthoughts. The Preludes are, essentially, experiments in sound: What are the possibilities of chromatic harmony and non-traditional scales? How can Spanish-guitar sounds, music-hall tunes, and dance rhythms be incorporated into piano miniatures? What colors can the black-and-white keys call forth in the listeners imagination?

Since musical talent usually reveals itself very early in life, it’s not surprising that Franz Liszt was a child-prodigy pianist. By his twenties, he was an internationally-famous virtuoso who was already becoming known as a composer. An interruption to his early career came in the form of Countess Marie d’Agoult, the first of the two great loves of his life, with whom Liszt escaped the public eye for several years in the mid-1830s, on an extended tour of Switzerland and Italy, reveling in the beauties of nature and art. He created a sort of musical diary, or travelogue, based on his impressions of the sights along the way. These took their final form, after much revision and afterthought, in two volumes of colorfully descriptive piano pieces he called “Années de pèlerinage” (Years of Pilgrimage). In the second set, “Italy,” he collected virtuosic pieces inspired by paintings he’d admired in Florence and Rome and by two of medieval Italy’s literary masters, Petrarch and Dante. Three pieces in the second volume were originally composed as songs: a trio of Petrarch’s sonnets in praise of his beloved Laura. In their keyboard form, the Sonetti del Petrarca reveal their origin as vocal pieces in their frank lyricism. They also display Liszt’s particular genius for exploiting keyboard sonority and using the sounds of his instrument to evoke romantic yearning.

Sonetto 47 begins with the word “Benedetto” (Blessed):

Blessed be the day, the month, the year

The season, the time, the hour, the moment

The lovely scene, the spot where I was put in thrall

By two lovely eyes which have bound me fast.

The lyrical opening melody gradually becomes more passionate, and the basic diatonic harmony becomes more chroma-tic, as the poet and composer reflect on the joy they derive from contemplation of the beloved. A highly chromatic cascade of chords adds to the mood of agitation. This instrumental sonnet is essentially monothematic, achieving variety through Liszt’s characteristic use of thematic transformation: constant, subtle variations that modify the same melody.

In Sonetto 104, “Pace non trovo,” Petrarch sets up a series of contrasts:

I find no peace, but for war am not inclined

I fear, yet hope; I burn, yet am turned to ice . . .

Eyeless I gaze, and tongueless I cry out . . .

I feed on grief, yet weeping, laugh.

Liszt expresses these unsettled emotions in part by straying almost constantly between major and minor modes. The piece’s agitated opening indicates the poet’s mental turbulence; its improvisatory nature conveys the sense of a mind (and heart) passing through a rapid progression of contrary moods; and all this is reinforced by chromatic harmonies used much more prominently than in Sonetto 47. Yet to conclude this declamatory storm of feeling, Liszt writes a quiet ending.

Sonetto 123 opens quietly, in reference to Petrarch’s vision of angels; he then compares this glimpse of heaven with the sight, once more, of Lady Laura’s lovely eyes, this time shedding tears. This sonnet has a very direct, very ‘singing’ main theme, which after a simple statement is elaborated in the piano’s highest register before being restated in the middle range. With ever-increasing elaboration, and a great deal of fast finger-work, a tremendous chordal climax first descends, then rises to the heights again. Through all the virtuosic passage-work, however, the theme that represents Laura and love remains audible. In conjunction with the word “Dolcezza” (Sweetness) in the sonnet’s final line, Liszt creates a peaceful coda full of yearning.

More than half a century separates the publication of Liszt’s first two “Années de pèlerinage” books (1852, 1856) and the appearance of Debussy’s Preludes, of which Volume One appeared in 1910 and Volume Two in 1913. During this time, musical language changed considerably. In contrast to Liszt’s keyboard sonnets, Debussy’s indefinite harmonies and evanescent melodies sound decidedly modern and different. He drew their titles, and perhaps their inspiration, from sources as varied as sculpture, drawings, legends, the world of nature, and poets from Shakespeare to the French Symbolists. Another major influence was the realm of dance music. “Danseuses de Delphes” (Delphic Dancers) is in the rhythm of a slow Baroque sarabande, possibly reflecting a sculpture from ancient Greece (housed in the Louvree). It’s a gentle opening for the first book of Preludes, full of mild and ruminative chords.

“Voiles” may be translated as either Sails or Veils; but whichever you envision, the music triumphs through its air of mystery. To achieve this, Debussy incorporates two unconventional scale patterns whose echoes will be heard throughout the Preludes. The whole-tone scale produces an exotically amorphous, unresolved sound. It can be reproduced on the piano keyboard by playing middle C followed by D, E, F-Sharp, G-Sharp, and A-Sharp/B-Flat. Since each interval is equal, no one tone stands out with special importance. In “Voiles,” somewhat faster-paced than its predecessor (“Modéré”), this scale lends a meandering feeling and establishes no tonal center. A middle passage exploits the pentatonic scale, a pattern that can be discerned in Native American, Anglo-American, Eastern European, and Asian folk and art music. Debussy probably first heard pentatonic music during the Paris Exposition of 1889, one of whose major attractions was a Javanese gamelan, the typical instrumental ensemble of Southeast Asia. (To reproduce the pentatonic scale on the piano, play middle C, D, E, G, and A, or start with F-Sharp and follow it with the next four black keys.)

There’s a strong tempo contrast in the “Animé” Prelude #3, “Le vent dans la plaine.” Here the melodic progressions are dominated by half-tone intervals, while repeated-note patterns give a sense of mildly puffing breezes, then a few big gusts that gradually die down. ‘the wind in the plain holds its breath” is a line from a celebrated 18th-century French poem. Poetry is also the source for the title of Prelude #4, “Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir,” a line from Baudelaire. Sounds and scents whirling in the evening air; the atmosphere is similar to that of “Delphes,” although the pace is a little faster. This is an improvisatory prelude that ruminates around the keyboard: very much like a gentle evening breeze.

From these inward-looking and somewhat indefinite sketches, we move to “Les collines d’Anacapri” (The Anacapri Hills) with a much more extroverted mood and a songlike middle section that could easily be derived from an Italian folk tune. Rippling figurations build up to a passage of great brilliance in the piano’s high register. “Des pas sur la neige,” however, returns us to the world of implication rather than declaration. Repeated, almost static rhythmic patterns suggest tentative steps through a heavy blanket of snow. The melodic motifs are hesitant, too, and lend the piece an improvisatory feeling, as though the music were literally feeling its way.

“Ce qu’a vu le Vent d’Ouest” has the word ‘tumultuous” as part of its tempo marking, and its atmosphere presents a powerful contrast to the frozen, muffled sound of “Neige.” Whatever the west wind might have seen, it carries threats with it. Penetrating trills and powerful chords dominate the texture; dissonant bass-register crashes are contrasted with brilliant figurations in the piano’s upper octaves. There have been various suggestions regarding the title’s origin. One is the Hans Christian Andersen story ‘the Garden of Paradise,” in which the four winds recount what they survey.

Another is a poem by Charles Grandmougin:

At night in the mayhem of the tempest

Who can tell if the clamour rising to the heavens

Is not the searing cry of souls in anguish?

Other votes go to Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”: “O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being . . . Wild spirit, which art moving everywhere.” There’s a recklessness about the music’s progressions that certainly suggests the Shelley poem, which Debussy knew in a French translation.

One of the best-known Preludes is “La fille aux cheveux de lin” (The Girl with Flaxen Hair). The serenity and beauty of this pentatonic musical portrait provide an oasis of calm after the stormy “west wind.” The title comes from one of poet Leconte de Lisle’s ‘scottish Songs.”

“La sérénade interrompue” (Interrupted Serenade) is cast in the Spanish jota rhythm. The detached, almost staccato playing style evokes the sound of a guitar. Strumming chords in the bass register may be heard as interruptions, or as accompaniments to the serenade tune. Like his contemporary Ravel, Debussy loved the sounds and rhythms of Spanish music and incorporated them into a variety of works, notably “Iberia” from his set of orchestral Images.

“La Cathedral engloutie” (The Engulfed Cathedral) is the most pictorial piece we’ve heard thus far. It’s also one of the most stunning pieces ever composed for the piano. There is a legend in Brittany, on the northwest coast of France, about a city called Ys that sank beneath the ocean, but whose majestic cathedral can sometimes be seen rising from the waves, only to sink again. The subdued chords that open the prelude and continue underneath the melody that at length emerges, represent the bells of the cathedral as it slowly, slowly, comes into view. The tempo marking throughout is “Calm,” and the harmonies are based on the pentatonic scale. The dynamic level builds and builds until the cathedral emerges triumphantly from the sea, fortissimo. Rumblings in the bass register, as the theme drops from the piano’s upper range to mid-range, show the water reclaiming its own . . . and the ghostly vision is gone.

“La danse de Puck,” marked “Capricious and Light,” evokes Shakespeare’s wood-sprite who famously declared, “What fools these mortals be.” No stronger contrast to “La cathedrale engloutie” could be devised. The dancing, fleeting motifs of this prelude caper off into airy nothingness. There’s dancing also in “Minstrels,” but it is far more anchored in reality: minstrels dance onstage, not in the air. A down-to-earth tune, played staccato, is supported by sturdy chords.

As with Book 1, Debussy starts off Book 2 with two pieces characterized by moderate-to-slow tempi and enigmatic moods. “Brouillards” means Fog, and the harmonies are indeed foggy, coming to no particular resolution until the final cadence. The impression is produced via chords based on half-tones. “Feuilles mortes” recalls the atmosphere of “Des pas sur la neige.” The dead leaves slowly falling, in no particular pattern, remind us that snow will soon follow. This is a slow-paced lament with indeterminate harmonies.

“La puerta del vino” picks up the pace as we hear a Spanish-Latin American habanera rhythm, with srongly syncopated accents that imply a slightly drunken dance by someone happily clutching a wine bottle. The title, after all, means Wine Port, or dock. The inspiration is supposed to have been a postcard scene from Spain, but perhaps Debussy simply wanted to place a more strongly-flavored, more energetic, Spanish-style piece next to its two more amorphous predecessors. In “Les fées sont d’esquises danseuses,” we hear a kind of scherzo that recalls not only “La danse de Puck” but also the elfin Scherzos of Mendelssohn’s string octet and “Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The fairy dancers do not perform an organized ballet; they improvise in a half-world half-lit by will-o’-the-wisps.

“Bruyères” may be translated as moor or heath; its straightforward harmonies and calm pace suggest a placid, expansive landscape and a far horizon. It also recalls Debussy’s early piano pieces, especially the two “Arabesques,” which like “Bruyères” feature rippling, decorative arpeggios. It provides an interval of gentle contemplation before we hear “Général Lavine – excentric.” This rollicking prelude is named for a music-hall dancer who’s portrayed via a cakewalk – a dance style popular in the early 20th century. Once again, Debussy seems to have placed this little vignette with its toe-tapping tunes as a deliberate contrast to the almost indeterminate sound of its predecessor.

“La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune” begins with quiet radiance and proceeds through chromatic, resonant harmonies to a brilliant sonic display representing moonlight emerging from behind the clouds. The haze returns to obscure the moonlight at the end. The title comes from a French newspaper account of Britain’s King George V being crowned Emperor of India in 1912. “La terrasse des audiences” may be translated as balcony, or some other kind of platform from which a monarch could survey his subjects. But the ruler here seems to be the moon. Is it the moon that’s holding court?

Another scherzo follows, echoing “Les fées,” as we glimpse the water-sprite Ondine in and out of evanescent motives. She evades us in the keyboard’s higher register just when it seemed she was going to make a clear appearance in the general area of middle C. Rippling figurations suggest her watery home. The legends of underwater spirits are often ominous; for example, the ancient Greek sirens who lured sailors to their deaths. This spirit, however, isn’t very threatening; she’s just mischievous. Her mood vanishes quickly as we hear “Hommage à S. Pickwick”: Debussy turns to the somewhat unexpected image of Dickens’s Samuel Pickwick to effect a change of mood and a different sound altogether, as we hear fast-paced chords and good-humored running melodies harmonized with almost no chromaticism at all. The mood changes once again as we hear somber, rich chords varied by light runs that only reinforce the atmosphere of contemplation. This is “Canope,” named for a type of ancient Egyptian funerary jar. Are we to envision death following the dancing of Pickwick, or is Debussy again looking for the greatest contrast in mood and texture?

“Les tierces alternées” (Alternating Thirds) starts slowly with patterns of thirds: two-note “chords” encompassing the interval of a third (C to E, for example). The pace picks up quickly as the thirds follow very rapidly one after another. This is the most virtuosic of the Book 2 Preludes so far. In the middle section, a strong melody emerges, harmonized in thirds, quickly overcome by the rapid motion of the beginning. Second-guessers have suggested Debussy should have placed this piece into his later collection of piano Etudes. But it could well be he wanted to insert a Prelude that, once again, clearly contrasts with what came before, and that would anticipate the brilliance of the final piece in the set, “Feux d’artifice” (Fireworks). This and “Les tierces” strongly recall the virtuosity of Liszt’s piano music. It’s an element not usually associated with Debussy’s keyboard works, but these fireworks are a tour de force of technique. “Feux” is by far the most directly exciting of the Preludes. It’s also extremely sonorous, using the entire range of the keyboard and the power of the sustaining pedal to depict a brilliant pyrotechnic display against the night sky. In keeping with the piece’s subject, there are patriotic echoes of “La Marseillaise.” Debussy saves a surprise for the end: after the final display, we see the fireworks die out as the sound slowly dies away.

Liszt parted from Marie d’Agoult not long after their journey through Switzerland and Italy. (One of their children, Cosima, married the conductor Hans von Bulow, and later, Richard Wagner.) Resuming his career as a pianist and composer, Liszt also assumed a conductor’s post in Weimar, Germany, introducing a great deal of his own music and also that of Berlioz and Wagner. A new love, Princess Carolyn of Sayn-Wittgenstein, entered his life, but they also eventually parted. In the 1860s, Liszt settled in Rome and took minor orders in the Roman Catholic Church. Among other compositional projects, he produced another set of “Années de pèlerinage,” this one subtitled Rome. Its contents, some religiously inspired, reveal the constant evolution of his harmonic genius and his continuing skill with tone-painting. “Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este” (The Fountain of the Villa d’Este) is one of the 19th century’s most brilliant demonstrations of pictorial music, and one of the most virtuosic pieces Liszt ever wrote, without ever putting virtuosity first. It’s a true pianistic tone poem, in the mode of the tone poems Richard Strauss would later create for orchestra. Brilliant, rippling figures show us the fountain in sparkling sunshine. We hear brief passages of staccato that suggest bouncing water droplets and dancing jets of water in sunlight. A new thematic variant is presented in the piano’s highest register, then the fountain totally opens up with powerful chords and runs that exploit the entire range of the keyboard. You can almost see the colors of the spectrum as the sun shines through the jets of water. Sparkling high notes and rippling bass patterns lead to a subsiding of the waters into a gentle repose.

“Les jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este” had a powerful influence on later composers, Debussy included. He evokes water sounds in the preludes “La Cathedrale engloutie” and “Ondine.”

Most of the pieces in Liszt’s first “Années de pèlerinage,” Switzerland, are about natural landscapes: storms, lakes, mountains. “Vallée d’Obermann” is about the landscape of the human heart. He based the work upon the eponymous novel by Etienne Pivert de Senancourt, about a man who tries to escape from the sorrows of his life in an isolated mountain refuge. The man and his grief are represented by one main theme, a descending minor scale, constantly transformed through subtle variants, transpositions between major and minor modes, and movement from the highest to the lowest registers of the keyboard. A wandering, chromatic motif opens the piece, to be succeeded by the strongly-defined main melody, first presented in the bass. When transferred to higher keys, and transmuted to the major mode, the theme sounds significantly different, but the agitation and yearning are still present. Rumbling in the bass leads to a dramatic passage with assertive, almost angry chords; is this a storm in the mountains or in the soul? The main theme returns, in major, indicating the possibility of peace, but agitation returns in a heavy chordal section, leading to a huge climax. Loneliness and anguish are present in each note of the theme, and these emotions are the work’s final impression.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time CD1: 60:04

Total Time CD2: 59:30

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover Photo: Peter Schaaf

Recorded: August 28 & 29, 2006 (Debussy) and February 8 & 9, 2007 (Liszt) at WFMT Chicago

Microphones: Sennheiser MKH 40, Schoeps MK 21

Steinway Piano – Piano Technician: Charles Terr

© 2007 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 098