| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

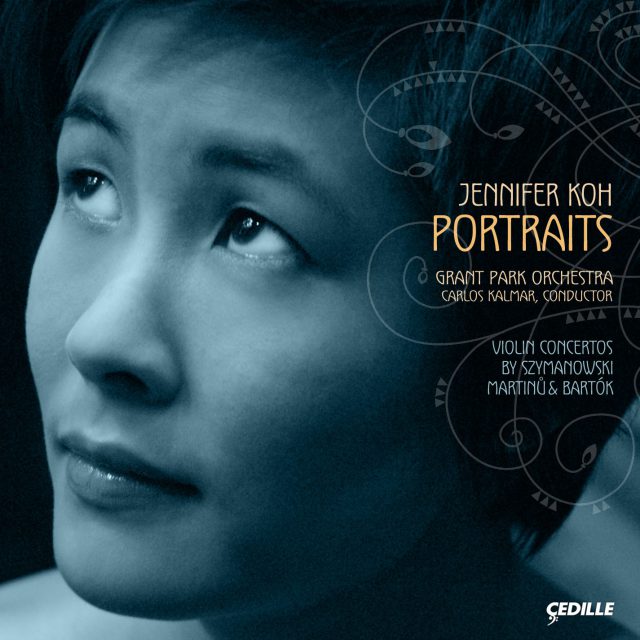

Violinist Jennifer Koh and Chicago’s Grant Park Orchestra, with prinicipal conductor Carlos Kalmar, perform compelling, rarely heard concertos by three innovative, twentieth-century European composers: Szymanowski, Martinu, and Bartok.

Preview Excerpts

KAROL SZYMANOWSKI (1882-1937)

BOHUSLAV MARTINU (1890-1959)

Violin Concerto No. 2, H. 293

BELA BARTOK (1881-1945)

Two Portraits, Op. 5

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletJennifer Koh — Portraits

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The works of Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937) took some time to achieve their rightful place in music history, and remain relatively unfamiliar in the United States. But they amply reward those willing to open their ears to a truly unique style, forged from eclectic influences into a poignant and highly individual sound. Like so many artists who emerged into adulthood around the turn of the 20th century, Szymanowski lived through the shattering of the old world order precipitated by World War I — an event that changed far more than national boundaries and the names of rulers. Old ways of living and thinking were destroyed; fortunes were lost; time-honored traditions were ridiculed and forgotten. Raised in a secure atmosphere of aristocratic privilege, enriched by his parents’ love for literature and music, the talented young pianist-composer grew up without the expectation of having to earn a living. His family’s estate was near Kiev in the Ukraine, but his family maintained strong ties to its roots in Poland. Home-schooled in both academics and music, Szymanowski moved to Warsaw in 1901 for studies at the conservatory. He soon joined other students in a movement that became know as Young Poland, which hoped to encourage more progressive, less provincial attitudes in the city’s musical establishment, and to find opportunities for the performance of their own compositions. Young Poland included the violinist Pawel Kochanski, who became Szymanowski’s lifelong friend, and a promising pianist named Artur Rubinstein.

Young Poland concerts were given in both Warsaw and Berlin in 1906; Szymanowski’s Concert Overture and Variations on a Polish Folk Theme drew favorable critical attention. New experiences now beckoned. Like other young men of means, he devoted his next few years largely to travel, visiting Berlin, Vienna, Paris, numerous Italian cities, Sicily, and North Africa. Eagerly opening his mind, spirit, and ears to these new environments, he absorbed influences including German late Romanticism, the works of Debussy and Ravel, Arab poetry and, most especially, the mix of ancient and medieval cultures he found in Sicily.

Szymanowski’s most important stage work, the opera King Roger, was premiered in Warsaw in 1926. Set in medieval Sicily, it vividly portrays a conflict between the conventional, ordered world of the Christian church and royal court that held sway in the Middle Ages and an older and perhaps freer system, harking back to the traditions of classical Greece. This older world is represented in the opera by a mysterious, charismatic figure called the Shepherd. King Roger reveals a great deal about Szymanowski, both intellectually and emotionally. Beyond the enthusiastic medievalism common to Romantic-era artists, it reflects the philosophical conflict often described as Apollonian vs. Dionysian: the light of reason contrasted with the “darker” impulses of the human psyche. In terms of Szymanowski’s own psyche, the opera conveys a large measure of sexual ambivalence. King Roger has a Queen but is also strongly attracted to the Shepherd: whether in physical or in spiritual terms is left unclear. Seen through contemporary eyes, King Roger expresses the anguish of a homosexual man trapped and repressed by the hereosexual hegemony of his time.

King Roger was several years in the future when Szymanowski returned to his parents’ home in 1914 to wait out the war and grapple with the myriad stylistic influences that affected his development as both a writer and a composer. As a Polish national, he was exempt from being drafted into the Russian army (Ukraine was then part of Russia) and would in any case have been disqualified for frail health: he suffered from the effects of a childhood injury, depression, and above all tuberculosis. His output during the war included an unfinished novel, his Symphony No. 3, Myths for violin and piano, Metopes for solo piano, songs on exotic themes from Arabian poetry, and the Violin Concerto No. 1, dedicated to his friend Kochanski, who contributed the virtuosic cadenza.

The Szymanowski family was forced off its estate in 1919, in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. The composer eventually settled in Warsaw and added yet another thread to the complex weave of his stylistic identity — that of the newly-resurgent Polish nationalist movement. He stayed in contact with Kochanski and Rubinstein during visits to Paris and the U.S., but increasingly spent time at a resort in Poland’s Tatra Mountains. Polish nationalism influenced a number of his late works, including a set of mazurkas, the ballet Hanasie, the String Quartet No. 2, and his choral masterpiece, Stabat Mater.

Now middle-aged and needing to earn money, Szymanowski embarked on a brief tenure as head of the Warsaw Conservatory, but found himself unhappy in an academic setting and artistically at odds with the faculty (though not with the students). He also undertook a career as a concert pianist despite his modest keyboard talents. Syzmanowski gained fame and respect in the 1930s through international performances of his compositions, but the effects of tuberculosis precluded further creative activity. He died in a Swiss sanatorium at the age of 54.

The Violin Concerto No. 1 represents a kind of early midpoint of Szymanowski’s continually-evolving style. A large, late-Romantic orchestra, augmented by piano and harps, supports and enhances an exuberant, rhapsodic solo part that tells us much about the virtuosity of the dedicatee, Pawel Kochanski. Three sections, the first two both marked Vivace, are performed without pause. The third is simply labeled Cadenza. The structure of the work is essentially that of a gigantic rondo, with a lyrical main theme transformed at each re-introduction between episodes of greater agitation, sometimes shared by the orchestra and soloist, sometimes presented in dialogue.

The large orchestra is not employed as a monolithic sound source. While there are many “tutti” passages, Syzmanowksi just as often spotlights an individual section — winds, horns, low strings — in the ongoing interchanges. Gustav Mahler famously broke up his huge orchestral forces into chamber-sized groupings; Szymanowski uses the same technique. Mahler, of course, never wrote a violin concerto. At times, it almost seems as if Szymanowski has done it for him. The influence of the late-Romantic music of Mahler and Richard Strauss is obvious, but in the end the work doesn’t sound like them: it sounds like Szymanowski.

Out of a frenetic orchestral opening gently emerges the first violin solo, calming and subtly dominating the texture. This sequence happens twice more, as the orchestra re-asserts itself and the soloist’s lyrical lines grow seemingly inevitably out of the surrounding agitation. These early violin solos establish both the main theme and the high range in which the soloist will play throughout most of the work.

Large symphonic climaxes, now majestic, now frenzied, separate the passages where the soloist reiterates and elaborates the main theme — which is presented at times in clear, diatonic, tonal fashion and at other times with more dissonant colors. The violin plays double-stops and dramatic running figurations up and down its full range, though the higher ranges are always the most prominent, reaching up to the instrument’s highest notes, imparting an intense sense of yearning. Leading up to the final section, the violin restates its main theme, which the orchestra takes it up briefly, but then stops abruptly as the soloist begins Kochanski’s cadenza, a brilliant collection of runs, chords, and octaves that brings the emotion of the piece to a climax. The orchestra responds with a full-strength coda that leads the violin on to one more triumphant statement of the main theme, soaring over an accompaniment that becomes gentle and restrained, presaging a sly, quiet ending.

Eight years younger than Szymanowski, Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959) spent his formative years in very different circumstances. Instead of living on a country estate, he grew up in a church bell tower, where his father worked three jobs: cobbler, bell-ringer, and town fire warden. The town was Polička in Bohemia, then a province of the Austrian Empire, now the Czech Republic. The boy showed amazing talent on the violin; townspeople helped his family raise money to send him to the Prague Conservatory in 1906. Though he never achieved academic success, the wider artistic horizons of Prague stimulated a number of his early compositions. A major event, pointing the way to future surroundings and experiences, was the 1908 Prague premiere of Debussy’s opera Pelleas and Melisande, a work that deeply affected and inspired Martinů. He grew disconcerted with conservatory routine and returned home, where the World War I cataclysm passed him by: never robust, he managed to avoid military conscription while continuing to compose and give music lessons. He would return to Prague to play violin in the Czech Philharmonic, and the first of his many travels abroad took place when the orchestra toured Western Europe, including Paris, in 1919. Four years later, he decided to abandon symphonic playing and returned to Paris to take advanced composition lessons with Albert Roussel.

In Paris, Martinů encountered not only the teaching of Roussel but also the revolutionary styles of Stravinsky and the iconoclastic group known as Les Six, which included Poulenc, Milhaud, and Honegger. Like them, Martinů was fascinated by the new transatlantic style called jazz. He was also influenced by the 1920s trends known as neo-Classic and neo-Baroque: a look back toward forms and instrumentations of the 18th century reinterpreted with 20th-century sounds. His works of the 1920s and Thirties were performed in Paris and also back home in the newly-created nation of Czechoslovakia. He also attracted the notice of Russian émigré conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who would have a powerful influence on his later career.

Perhaps his most important encounter in Paris, however, was with Charlotte Quennehen, whom he married in 1931. A professional dressmaker and woman of exceptional resourcefulness, steadfastness, and loyalty, she stood by her husband through poverty, infidelity, exile, and illness. The Martinůs’ situation in Paris became precarious in the late 1930s, after the Nazis took over Czechoslovakia. As the Czech opposition’s cultural attaché in Paris, Martinů aided a number of Czech artists who tried to find refuge in France, but the approaching Nazi occupation forced him to become a refugee himself. In 1940 the couple left Paris for Marseilles, then Lisbon, then New York.

Martinů found teaching positions at Vermont’s Middlebury College and at Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony, but was afflicted by depression, homesickness, and a lack of English fluency. He never adjusted well to life in the United States, but it was in this country that his compositional career really took off, thanks to Koussevitzky, who had left Paris to become music director of the BSO. One of the most remarkable conductors of the 20th century, Koussevitzky had a passionate commitment to new music and to encouraging talent. His foundation commissioned countless compositions and he mentored Leonard Bernstein among many others. Commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation, Martinů’s Symphony No. 1 was premiered by the Boston Symphony in November 1942. In the audience was the celebrated violinist Mischa Elman who, at Koussevitzky’s suggestion, asked Martinů to write a new violin concerto, which Elman first performed in Boston, December 1943.

Continually encouraged by Koussevitzky, Martinů wrote four more symphonies during the 1940s and continued his teaching activities, but still felt alienated from American life. He returned to Europe, though never to Czechoslovakia, and died of cancer in Switzerland in 1959. His remoteness from the land of his birth, oppressed first by fascism, then by communism, led him to take some inspiration from Bohemian folk music. It’s a major thread in his compositional fabric, alongside the many other influences he assimilated into a vigorous, sometimes abrasive, but always attention-compelling style.

Mischa Elman was an exuberant and virtuosic violinist. Martinů (a violinist himself) seems to have understood his new patron practically on first contact and crafted for him an extroverted work that blends tunefulness, dissonance, and rhythmic complexity into a meaty romp for both soloist and orchestra. If Martinů was depressed about being an émigré in a strange land while the world was plunged into a frightful war, those circumstances seem largely to have been put aside here.

A dramatic opening statement in the orchestra dies down to let the soloist enter with an athletic theme that transforms into a more lyrical statement. There’s a sense of dialogue between soloist and orchestra that is constantly disturbed by rhythmic displacement: accents are not on the first note of the bar. You can see it if you’re looking at the score, but that’s not necessary: you can hear it in the energetic edginess the music acquires as it progresses. The moderate Andante tempo of the opening shifts to Poco Allegro; the violin quickens the pace and the orchestra responds to its scurrying arpeggios with a big “tutti” climax. The rhetorical exchanges continue until a dissonant orchestral chord ushers in the soloist’s first cadenza, which ruminates on all the themes introduced earlier and further elaborates them. A lyrical passage marked Moderato ends the movement.

The Andante Moderato middle movement begins with a folklike theme in the orchestra and a gorgeous solo for the violin, gently supported by the orchestra. The tempo picks up in the solo part and then slackens again as the orchestra restores the bucolic opening mood enhanced with rich harmonies. Solo winds usher the violin back into a short cadenza-like passage that leads to a quiet end.

The Poco Allegro finale starts out with the soloist leading a village dance. Rapid figurations and fleeting motives are tossed back and forth between violin and orchestra. The dance briefly becomes an orchestral march tune, but the soloist turns the mood back into a dance, with octaves, double-stops, and virtuoso patterns that exploit the intrument’s full range. The orchestra responds with a declamatory statement dominated by the brasses, then in rondo fashion the violin returns to prominence with its dance. Martinů provides the soloist with cadenza that introduces a touch of melancholy, but sunshine returns as soloist and orchestra plunge together into a brilliant final celebration of the dance.

The oldest of the three composers on this CD, Béla Bartók (1881–1945) was also the most revolutionary. One of the dominant musical geniuses of the 20th century, a master of stage, symphonic, chamber, and solo genres, Bartók was also a pioneer in the realm of ethnomusicology — the study of regional folk music. This he explored in his native Hungary and surrounding nations with the help of his friend and fellow-composer Zoltán Kodály, and the new technology of recording. Both Szymanoski and Martinů were influenced by folk music; Bartók transformed it into an essential element of his style. The motives and rhythms of indigeous Eastern European songs and dances would emerge in stage works, string quartets, and his powerful Concerto for Orchestra.

Another profound influence on the young Bartók was his love for the talented violinist Steffi Geyer, who is remembered in a long-suppressed concerto, now known as his Violin Concerto No. 1, and in the Two Portraits composed in 1907–08 and 1911, respectively. (The first movement of the concerto is identical to the first movement of Two Portraits.) The portraits are a reflection of their broken love affair. In the first part, titled “Idealistic,” the solo violin opens with a lyrical theme in the instrument’s low-to-medium register, with a progression based on the notes D-F#-A-C#, a modified and dissonantly-inclined scale pattern. The theme turns sinuous and chromatic as the unobtrusive orchestral accompaniment gradually gains attention by intertwining with the soloist. The violin dominates, however, by playing with ever-increasing intensity, then retreats into meditation. The opening theme returns in the violin part, and leads to a big climax in partnership with the orchestra. Supported by a harp, the violin soars into a final statement of the love song.

In the second Portrait, the solo violin is silent. The orchestra takes up the original four-note theme and mocks it. This movement is labeled “Distorted,” and that is exactly what Bartók does: he distorts the lyrical atmosphere of the opening into a strident, dissonant dance dominated by hammering percussion, blaring brass, and scrambling woodwinds. The pace is headlong. The love song of the first movement has disintegrated into bitterness.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time: 65:15

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Eric Arunas and Bill Maylone

Recorded “Live” in Concert: July 1 & 2, 2004 (Szymanowski) and July 1 & 2, 2005 (Martin, Bartok) at the Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Millennium Park, Chicago

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond, Pete Goldlust

Front Cover Photo: © Sarah Shatz

© 2006 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 089