| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

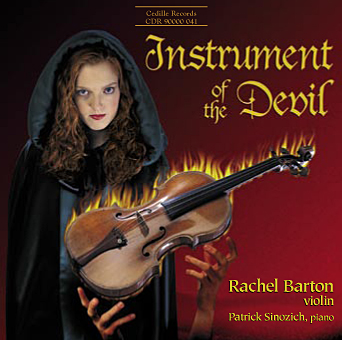

On Instrument of the Devil, gifted young violinist Rachel Barton Pine displays her technical prowess and the instrument’s emotional range in an unusual, virtuosic program that, in her words, offers listeners something other than “the usual potpourri of encores.”

This CD explores the mythic and frequent literary associations of the violin with death the Devil, inspired in part by pianist Earl Wild’s recording of Liszt’s music on diabolical themes (The Demonic Liszt), Miss Barton says. An essay by musicologist Todd E. Sullivan of Indiana State University traces the origins of the violin’s otherworldly associations back to ancient Greek religious cults, who identified musical instruments with deities and their ethical attributes. By the 1500s, violins were linked with dancing, an activity denounced by religious conservatives. Tales of demonically endowed fiddle players first emerged during the 17th century — an image that endures in today’s pop culture.

Preview Excerpts

CAMILLE SAINT-SAENS (1835-1921)

GIUSEPPE TARTINI (1692-1770)

Sonata in G minor, "The Devils Trill"

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886) / tr. Milstein

ANTONIO BAZZINI (1818-1897)

HECTOR BERLIOZ (1803-1869) / tr. Barton-Sinozich

MANUEL DE FALLA (1876-1946) / tr. Kochanski

HEINRICH WILHELM ERNST (1814-1865)

NICOLO PAGANINI (1782-1840)

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

PABLO SARASATE (1844-1908)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album Booklet"INSTRUMENT OF THE DEVIL"

Notes by Todd E. Sullivan

ZIG AND ZIG AND ZIG. DEATH IN CADENCE

KNOCKING ON A TOMB WITH HIS HEEL,

DEATH AT MIDNIGHT PLAYS A DANCE TUNE

ZIG AND ZIG AND ZIG, ON HIS VIOLIN.

-from a poem by Henry Cazalis, alias Jean Lehor

Associations between the violin and death or the devil reside deep in the modern Western consciousness. Traditional, popular, and classical music cultures have reinforced this viewpoint many times over. The identity of the “Devil as fiddler” has evolved in stages over the past two millennia or longer as numerous religious beliefs, folk legends, and literary tales merged to produce a central myth.

Roots of this myth trace back to ancient Greek religious cults. Instruments were commonly associated with specific deities and their ethical attributes. The reed-pipe aulos, for instance, belonged to the decadent cult of Dionysius (Bacchus in Roman mythology). Aristotle pronounced the aulos “not an instrument that expresses moral character; it is too exciting.” The lyre and kithara were connected with Apollo, the god of music, healing, archery, and the sun. Accordingly, string instruments were thought to possess enormous restorative powers.

This correlation between musical instruments and moral states appealed to early Christians. Medieval society invoked music to rationalize the constant intrusions of warfare, plague, and death. In literature and folk lore, the sound of pipes frequently accompanied Death on his gruesome rounds. During the Middle Ages, string instruments enjoyed quite different affiliations. Ecclesiastical artists commonly selected the soft-toned vielle, rebec, or lira for symbolic representations of goodness and the divine. Saintly figures, angels, and cherubim often held these mellow-sounding instruments in hand. Thus, the ancient Apollonian stereotype was retained for centuries in Western Europe.

The mid-sixteenth-century emergence of a new family of strings, including the violin, changed everything. The violin’s popularity grew with enormous swiftness, primarily because of its loud tone and secure tuning. It soon became the preferred accompaniment for dances, weddings, and other outdoor entertainments. Philibert Jambe de Fer added in his Epitome Musical (1556) that the violin “is also easier to carry, a very necessary thing while leading wedding processions or mummeries [comic entertainments by masked actors or musicians].”

The earliest artistic renderings of the violin date from the 1570s. In these, peasant performers accompany group dancing, an activity denounced in the afterglow of the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation. Many writers blamed the Devil for the very existence of dance. The Devil, as the agent of Death and creator of dance, became inextricably linked to the violin during the Renaissance period. According to musicologist Rita Steblin, the visual and literary arts differed in their portrayals of this fiendish musicmaker. Paintings such as Pieter Brueghel’s “The Triumph of Death” (c.1562) and Hendrik Goltzius’s “Couple Playing, with Death Behind” (17th century) perpetuated the skeletal image of Death. Written documents tended to characterize Death as the Devil himself.

Tales of demonically endowed fiddle players first emerged during the seventeenth century. The Englishman Anthony Wood described in his diary (July 24, 1658) an awe-inspiring performance by German violin virtuoso Thomas Baltzar. A respected music professor in attendance “did after his humoursome way, stoop downe to Baltzar’s feet to see whether he had a huff [hoof] on, that is to say, to see whether he was a devil or not, because he acted beyond the parts of Man.” The eighteenth-century Italian violinist Giuseppe Tartini raised the degree of diabolical intervention with his claims of a dreamy pact with the Devil.

Tales of supernatural contracts between musicians and the Devil proliferated during the nineteenth century, fueled by the immensely popular story of the scholar Faust and his calamitous pact with Mephistopheles. Many people believed the only explanation for Nicolo Paganini’s unparalleled violin technique was a Faustian alliance with the Devil. The Italian violinist parlayed this demonic mystique into a phenomenally lucrative concert career. Furthermore, the superhuman virtuoso image – long hair, angular features, sly grin, and slender figure – originated with Paganini.

Condemnation of the violin as an instrument of the Devil spread during the nineteenth century to other parts of Europe and North America. Churches in Sweden and Norway outlawed the violin and created a substitute string instrument, the psalmodikon, to accompany hymn singing. Scandinavian settlers transported this “bowed zither” to the Upper Midwest region of the United States. Calvinist adherents in the British Isles denounced the violin because of its evil associations with dance. Such prejudices also traveled with some Scots-Irish immigrants to the U.S. Numerous British folk ballads and fiddle tunes, transplanted to Appalachia and other parts of the country, make reference to the Devil.

The relationship between the Devil and string music has resurfaced in recent popular music. Bluesmen believed that if a guitarist reached the crossroads at midnight, he would receive supernatural virtuosic abilities in exchange for his soul. Early blues-inspired rock artists – among them the Rolling Stones, Cream, and Led Zeppelin – perpetuated this mystical aspect. Heavy metal artists consciously adopted Paganini’s nineteenth-century virtuoso image in their powerful stage presence, styles of hair and clothing, and musical pyrotechnics. The electric guitar provides a modern high-voltage equivalent to the violin. No contemporary song better illustrates the persistence of the “Devil as fiddler” than the 1979 country-rock hit “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” by the Charlie Daniels Band. The Devil encounters a young man “who plays the fiddle hot” and challenges him to a musical duel, the outcome of which is unexpected: After centuries of bargaining, humankind has finally produced a musician whose natural skills surpass the Devil’s.

Four symphonic poems lie buried within the enormous orchestral catalogue of French composer, organist, and pianist Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921). The first, second, and fourth drew their inspi- ration from the mythological accounts of Omphale, Phaeton, and Hercules. The third, however, corresponded to a contemporary poem by Henri Cazalis (alias lean Lahor). These verses, quoted above, tell of a frenzied demonic dance that takes place after the stroke of midnight – the witching hour. Saint-Saens completed his Danse macabre in 1875 and published the score a year later. He also made several arrangements, including for violin and piano and for two pianos.

Some orchestral players rebelled against the literal representation in Danse macabre and only reluctantly participated in the premiere at a February 3, 1875 program of the Concert National under Edouard Colonne. The critic Adolphe Julien complained that the piece “has everything but a musical idea, good or bad.” He continued by describing it as either “an aberration or a hoax.” Audiences, on the other hand, took enormous glee in the fiendish orchestral score. The bells toll midnight on All Hallow’s Eve. Death, playing an oddly mistuned violin, summons skeletons (depicted in the orchestral version by the rattling “bones” of a xylophone) from their graves to dance a macabre waltz- an ominous parody of the Dies irae chant from the Mass for the Dead. These spectral figures dance until the rooster crows dawn, then they return to their tombs until the next year.

Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) was born in Pirano, Istria (then part of the republic of Venice, now located in Slovenia). His family encouraged him to enter the priesthood, but Tartini opted for a career in law and an avocation as a fencer. His marriage in 1710 resulted in further conflict with church authorities, and he fled to a monastery at Assisi where he resolved to become a professional violinist. Tartini spent the majority of his career as principal violinist and leader of the orchestra at St. Anthony’s Basilica in Padua, except for short periods in Venice and Prague. In addition to his sonatas and concertos, he wrote and published several influential treatises on violin and bowing technique and on theoretical and acoustical aspects of music.

The Sonata in G Minor, known as the Devil’s Trill, is shrouded in mystery. During a visit to Padua, the French astronomer Joseph Jerome de Lalande heard Tartini relate his Faustian story:

“One night in 1713, [Tartini] dreamed that he had made a contract with the Devil, who happened to be in his service. Whatever Tartini wanted was granted to him, and all his wishes were anticipated by his new servant, who gave him a violin to see if he could play anything harmonious. But what was Tartini’s surprise when he heard [himself play] a sonata so original and lovely and performed with such perfection and meaning that he could never have imagined anything like it! He experienced such amazement, admiration, and delight that he was breathless. His strong emotion woke him, and he immediately seized his violin in the hope that he would be able to remember at least part of what he heard, but in vain. The piece that Tartini composed then is indeed the best of all that he has ever done, and he calls it The Devil’s Sonata. But the former one that amazed him was so much better than his own that he would have broken his violin and given up music forever if only he could have had it.”

Tartini’s programmatic writing is not limited to this work; other sonatas are named Didone abbandonata (Dido Abandoned), The Emperor, and The Dear Shade. Many have questioned the date of Tartini’s fiendish dream and the resulting Devil’s Sonata, suggesting alternate dates between 1720 and 1740. A gentle siciliano sets a tranquil scene before the demonic encounter. The subsequent movement, performed in the “appropriate tempo of the Tartini school,” provides a lively preamble to the dramatic finale. Tartini composed an unusual final movement in which slow segments, entitled “The Dream of the Master,” alternate with faster portions containing the celebrated “Devil’s Trill.”

Many modern violinists perform from Fritz Kreisler’s edition. Kreisler eliminated double-stops in the siciliano, included his own harmonies (different from the sometimes jarring chords indicated by Tartini’s bass line in the accompaniment), and added a cadenza before the end of the final movement. Rachel Barton performs from the first edition, published by jean Baptiste Cartier in his L’Art du Violonou Collection Choisie clans les Sonatas des Ecoles Italienne, Francaise et Allemande, an anthology issued in Paris in December 1798.

The Hungarian pianist Franz Liszt (1811-86) emulated Nicolo Paganini’s transcendant virtuosity and stage demeanor and, like Paganini, Liszt was believed to have given his soul to the Devil in exchange for his exceptional musical abilities. Amy Fay, one of Liszt’s American students, characterized him in diabolic terms: “His mouth turns up at the corners, which gives him a most crafty and Mephistophelean expression when he smiles, and his whole appearance and manner have a sort of Jesuitical elegance and ease. . . He is all spirit, but half the time at least, a mocking spirit.” Even after taking minor orders in the Catholic Church, Liszt was described as “Mephistopheles disguised as an abbe.”

His compositions exhibit a similar affinity for the Faustian model. In addition to his Faust Symphony, based on Goethe’s account, Liszt composed Two Episodes from Lenau’s Faust for orchestra. Compositions for the piano inspired by the Faust legend include the Mephisto Polka, a transcription of a waltz from Gounod’s Faust, and four Mephisto Waltzes. Liszt’s first Mephisto Waltz, written in Weimar around 1860, outlines events in the Faust legend. Faust and Mephistopheles enter a village inn as wedding festivities are underway. Mephistopheles snatches the violin away from one of the peasants and tunes it string-by-string before playing his frenzied dance. The music slows for a captivating new theme as Faust tries to seduce one of the maidens. Again, the Devil’s dance rouses the revelers. The nightingale pipes a tune, and Faust slips off into the woods with his young mistress. Nathan Milstein (1904-92), the celebrated Russian-born violinist, transformed Liszt’s first Mephisto Waltz into a monstrously challenging piece for solo violin.

Very early in his career, the Italian violinist Antonio Bazzini (1818-97) garnered extraordinary praise from Robert Schumann in the Neue Zeitschrift fur Musik (1843):

“As a player, he ranks among the greatest of the day. I cannot recall one who excels him in remarkable execution, in grace and fullness of tone, and especially in clearness and lasting power. He exceeds the majority in the original freshness, youthfulness, and soundness of his performance; and when I realize to myself the heartless, soulless, blase nature of many- especially Belgian- virtuosos, he seems to me a manly, blooming youth among worn-out greybeards; while a yet more brilliant future smiles before him, although he now stands on such a shining height.”

A native of Brescia, Bazzini acquired phenomenal technical skill as a youth. His prodigious abilities attracted the attention of his countryman, Nicolo Paganini. Bazzini made numerous recital tours, beginning in 1840, that traversed Europe. He lived in Germany from 1841 to 1845, and Paris between 185 2 and 1863. The year of his Paris debut (1852), between acts of an opera at the Theatre-Italien, Bazzini composed his character piece Round of the Goblins (Fantastic Scherzo), Opus 25 for violin and piano. Bazzini joined the composition faculty of the Milan Conservatory in 1873 and became its director nine years later. His students included a distinguished group of opera composers: Alfredo Catalani, Pietro Mascagni, Nicolo Massa, and Giacomo Puccini.

The Irish actress Harriet Smithson, who appeared as Ophelia in a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Paris, bewitched the young French composer Hector Berlioz (1803-69): “The impression made on my heart and mind by her extraordinary talent, nay her dramatic genius, was equaled only by the havoc wrought in me by the poet she so nobly interpreted.” The love-struck musician did not meet Smithson before she returned to England in 1829. Nonetheless, his idealized memory of her developed into obsessive infatuation. When rumors of a tryst between Smithson and her manager circulated in Paris, Berlioz flew into a jealous rage. The imagined betrayal provided a scenario for a programmatic symphony formulating in his mind: the Fantastic Symphony (Episode from the Life of an Artist), Opus 14. Its story involves an artist who falls in love with a flawless, ravishing woman. Clearly, Berlioz portrayed himself as the artist. The woman’s identity was equally obvious to Smithson, who attended a performance of the Fantastic Symphony and its sequel (the melodrama Lelio, or the Return to Life) on December 9, 1832. Berlioz finally encountered the flattered actress the next morning, and the two married within a year, unhappily as it turned out.

Several revolutionary aspects of Berlioz’s Fantastic Symphony provoked attacks from Parisian conservatives. The orchestra was extremely large and diversified. In addition, Berlioz had devised an innovative means of recalling the Beloved throughout the Fantastic Symphony by means of a distinctive melody, called the idee fixe, which appears in each movement. The character of the theme is transformed as the artist’s vision of the Beloved changes. The returning melody adds cyclic unity. Berlioz expanded the standard four-movement symphonic structure to five movements, each with a descriptive title drawn from his published program notes.

The symphony climaxes with the drug-induced “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath.” Evil figures of every imaginable type surround the young artist. His Beloved’s theme appears disfigured and lacking “its character of nobility and shyness.” Funeral bells toll, followed by the Diesirae chant. The witches begin their round dance, which later combines with the Diesirae.

Following the nineteenth-century tradition of chamber transcriptions of symphonic scores, Rachel Barton and Patrick Sinozich arranged this movement for violin and piano. Miss Barton and Mr. Sinozich consulted both Berlioz’s full score and Liszt’s solo-piano transcription (provided courtesy of the Liszt Society of London) while deciding collaboratively on the distribution of thematic material and adaptation of orchestral sonorities.

El amor brujo (Love, the Magician) was born of mystical gypsy blood. Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) had returned to Madrid in 1914 following a seven-year residency in Paris. The musician soon received an invitation from dramatist Martinez Sierra to collaborate on “one song and one dance” for the great Andalusian flamenco dancer, Pastora Imperio, the most celebrated member of a family of gypsy entertainers. Sierra and Falla absorbed gypsy folk songs and tales from Rosario la Mejorana, Imperio’s mother. This modest commission quickly expanded into a full-scale “gitaneria,” a gypsy ballet with songs in two scenes. Falla responded with uncharacteristic speed, completing the score between November 1914 and April 1915.

The ballet portrayed an unfamiliar facet of Andalusia, the gypsy communities dwelling in the Sacro Monte caves near Granada. The beautiful, hot-blooded gypsy girl Candelas has fallen in love with Carmelo. Their rendezvous comes to a terrifying end when the ghost of Candelas’s former lover provokes the jittery “Dance of Terror.” Falla imitates an old gypsy dance known as the baile de la tarantula, closely related to the Italian tarantella. Polish violinist Pawel Kochanski (1887-1934), also familiar as the arranger of Falla’s Suite populaire espagnole, transcribed the “Dance of Terror” and other El amor brujo excerpts for violin and piano.

The premiere production of El amor brujo, given at Madrid’s Teatro Lara on April 15, 1915, featured members of Imperio’s family: her brother, a sister-in-law, and her daughter, Maria del Albaicin. Unfortunately, the piece disappointed critics and ticket-holders alike. Falla later revised his score as a concert suite (1916) and a pure ballet without singing. The latter achieved considerable success at its premiere in Paris’s Trianon-Lyrique on May 22, 1927, on a program containing another supernaturally inspired piece, Stravinsky’s L’histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Tale).

“Ernst was the greatest violinist I have ever heard. He towered above all others.” This endorsement by Joseph Joachim (the violinist identified with Johannes Brahms’s solo violin works) was superlative praise during the age of virtuosos. Some listeners claimed Ernst’s technique surpassed even Paganini’s. A native son of Moravia, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1814-65) entered the Vienna Conservatory at eleven for studies in violin with Joseph Boehm and composition with Ignaz Xaver, Ritter von Seyfried. After attending one of Paganini’s performances in Vienna, Ernst devoted himself to attaining equal heights of virtuosity. His astounding technique shone through every original set of variations, poetic movement, and concerto for violin. Ernst composed the Grand Caprice on Schubert’s Der Erlkonig, Opus 26 in Hamburg in 1854. Each aspect of Schubert’s demonic song (based on a text by Goethe)- galloping triplets, frantic cries for help, the alluring, deadly entreaties of the Erl-King, and the father’s desperate attempts to comfort his dying son- is transferred to the unaccompanied violin, producing one of the most difficult works ever written for the instrument.

One of the most popular melodies of the early-nineteenth century came from the ballet Die Zauberschwestern im Beneventer Walde (The Magic Sisters in the Beneventan Woods), produced in 1802 in Vienna. Franz Xaver Sussmayr (known for his completion of Mozart’s unfinished Requiem) wrote the score, and Salvatore Vigano created the choreography. Vigano staged numerous acclaimed ballets for the Hoftheater, including Beethoven’s The Creatures of Prometheus, in the early part of the century. He revised the Sussmayr collaboration as Le nozze di Benevento for an 1813 performance at La Scala in Milan. Audience and critical reactions were mixed: some praised Vigano’s innovative production, while others decried the “hodgepodge of diabolical and grotesque inventions.” The ballet made a lasting impression on at least one attendee, the violin virtuoso Nicolo Paganini (1782-1840), who soon composed a set of variations on Sussmayr’s music for the entrance of the witches. (Beginning violinists today will recognize this tune from Shinichi Suzuki’s Book 2. Some teachers have their students dance a “witches dance” while playing this piece.) Paganini entitled his variations Le streghe (The Witches), opus 8, although one English-language publication called them Paganini’s Dream.

A grand, majestic introduction for violin and piano acquaints the listener with tempo changes built into Sussmayr’s theme and the virtuosity of the ensuing variations. Three central variations and an intermediate section marked “Minore” display Paganini’s whole bag of virtuoso tricks: multiple stops in Variation I; rapid crossings over multiple strings, pizzicatos, and harmonics in Variation II; chromatic runs in octaves in the Minore; and runs up and down the G string alternated with multiple harmonics in Variation III. After all this, the Finale presents a blazing display of violin pyrotechnics, including runs, arpeggios, and harmonics played high on the instrument’s G-string.

Technical difficulties inherent in Le streghe combined with the enchanted subject matter helped foster the growing association between Paganini and the Devil. A Viennese gentleman envisioned a demon hovering over the violinist as he performed this music. Paganini published a letter, with the help of Francois-Joseph Fetis, in the Revue musicale (183 1) describing this “ridiculous” event: “One individual, who appeared to me of a sallow complexion, melancholy air, and bright eye, affirmed that he . . . had distinctly seen, while I was playing the variations, the Devil at my elbow, directing my arm and guiding my bow. My resemblance to [the Devil] was a proof of my origin. He was clothed in red, had horns on his head, and carried his tail between his legs.” Paganini attempted to dissociate himself from the demonic image, going so far as to publish a loving, God-filled letter from his mother in a Prague newspaper (1828) as evidence against rumors that he was the Devil’s son.

Nature did little to assist these efforts. The violinist suffered from constant ill health that left him lanky, drawn, and pale. Paganini began taking a popular elixir that apparently caused depression and stage fright. His dispassionate stage presence grew more startling when Paganini had his bottom teeth removed – perhaps another unfortunate result of his “medical” treatment – leaving his mouth in a permanent devilish smirk.

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) discovered two folk stories about the encounters of a Soldier with the Devil while leafing through a published folk collection that Alexander Afanasiev compiled during the brutality of the Russo-Turkish wars. Stravinsky mentioned these tales to novelist C.F. Ramuz, who immediately recognized their theatrical potential. Collaboratively, they conceived L’histoire du soldat (The Soldier’s Tale), a stage narration with incidental music for chamber ensemble. The first performance took place at the Theatre Municipal in Lausanne, Switzerland on September 28, 1918.

The normally “objective” composer experienced a haunting vision while writing this piece. Stravinsky imagined “a young gypsy sitting by the edge of the road. She had a child on her lap for whose entertainment she was playing a violin . . . The child was very enthusiastic about the music and applauded it with his little hands.” The fiddle became an essential element in the final storyline, though nothing of the gypsy or her child survived.

On his way home after the war, a Soldier encounters the Devil dressed as an old man. The Soldier exchanges his fiddle (a metaphor for his soul) for a magic book. The Devil invites him to spend three days with him. Once arrived in his home village, the Soldier realizes he’s been gone three years, not three days. The military man attempts to buy back his fiddle, but finds that he can produce no sound from it. The Soldier throws away the instrument and destroys the magic book. Later, he wins a card game with the Devil, now disguised as a virtuoso violinist, and recovers the fiddle. The Soldier’s music revives a sleeping Princess, winning her hand in marriage, The Devil next appears as himself. The Soldier fiddles him into unconsciousness (“The Devil’s Dance”) then drags away his body. After their marriage, the Soldier and the Princess return to the village, where the Devil again enchants the young man and steals his fiddle a final time.

With L’histoire du soldat, Stravinsky cut final ties with his “Russian period” style. He opted instead for several popular “Western” musical types- march, tango, waltz, ragtime, and pasodoble – in addition to the more solemn Protestant chorale and, of course, the Diesirae. Stravinsky made two arrangements of his Soldier’s Tale music: a five-movement suite for violin, clarinet, and piano (1919) and an eight-movement orchestral suite (1920). “The Devil’s Dance” performed on this recording comes from the trio version.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s epic telling of the Faust legend bewitched nineteenth-century France. Its clash between sacred and profane, pure love and unbridled lust, eternal condemnation and redemption inflamed poets, visual artists, and composers (Schubert, Berlioz, and Liszt, among many others) of the Romantic age. This tale captivated Charles Gounod (1818-93) during his year of study at the French Academy in Rome after he received the Grand Prix de Rome in 1839. Nineteen years later, Gounod initiated a collaboration with impresario Leon Carvalho at the small Theatre-Lyrique, after the Opera de Paris rejected his proposed Faust opera. The source of Jules Barbier’s libretto was an 1850 “boulevard” play, Faust et Marguerite, by Michel Carre (also one of Carvalho’s resident authors). Like many French adaptations of Faust- either in novel, play, or visual form- Carre chose to spotlight the character of Marguerite (Gretchen in Goethe’s version). The opera takes place in a sixteenth-century German village. Doctor Faust bemoans his meaningless existence and enters into a fiendish contract with Mephistopheles. Gounod’s Faust opened on march 19, 1859, and enjoyed a respectable run of fifty-nine performances.

Gounod’s themes enjoyed widespread dissemination through sheet music publications and instrumental fantasies or potpourris. (Opera was considered a form of popular entertainment during the nineteenth century, and virtuoso performers frequently included operatic fantasies on their solo programs.) At least three violinist-composers created Faust fantasies: Henryk Wieniawski, Henri Vieuxtemps, and Pablo Sarasate (1844-1908). Sarasate began, in traditional fashion, with his own fantastic introduction. The operatic excerpts observe the following sequence (based on the five-act edition): Marguerite’s Prayer from Act IV (“Seigneur, accueillez la priere,” Mephistopheles’s Song of the Golden Calf from Act II (“Le veau d’or est toujours debout”), Faust and Marguerite’s duet from Act III (“0 nuit d’amour”), a brief extract from Faust’s Act III cavatina (“Salut! demeure chaste et pure”), and part of the Act II waltz with chorus sung by the youthful Siebel (“C’est par ici”).

The son of a Spanish military bandmaster, Sarasate began his musical studies at the age of five. Sarasate gave his first public performance on the violin at age eight. With the financial backing of Queen Isabella, he went to Paris in 1856 to con tinue studies at the Conservatoire. He won first prize in violin and solfege the following year and a first prize in harmony in 1859. One of the great violin virtuosos of his day, Sarasate made his first tour of Europe in 1859. Later tours took him to England and North and South America.

Todd E. Sullivan is Assistant Professor of Music (musicology) at Indiana State University and is program annotator for the Ravinia Festival.

A “DEVILISH” READING LIST

CANSLER, LOMAN D. “The Fiddle and Religion.” Missouri Folklore Society journal 13-14 (1991-92): 31-43.

MICHEL, JOHANNES. “Tanz und Teufel: Zu ausgewalten Musikdarstellunden mittelalterlicher Sakralkunst am Oberrhdin.” In Musik am Oberrhein. Kassel: Bosse, 1993. Pp 13-29.

SCHMIDT-GARRE, HELMUT. “Der Teufel in der Musik.” Melos Vol. 1, No. 3 (1975): 174-83.

STEBLIN, RITA. “Death as a Fiddler: The Study of a Convention in European Art, Literature, and Music.” Basler Jahrbuch fur Historische Musikpraxis 14 (1990): 271-322.

WALSER, ROB. Running with the Devil: Power, Gender and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hannover, NH: University Press of New England, 1993.

WALTER, MICHAEL. “Der Teufel und die Kunstmusik: Zur Musik der Karolingerzeit.” Das andere Wahrnehmen: Beitrage zur europaischen Geschichte: August Nitschke zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet. Edited by Martin Kintzinger, Wolfgang Sturner, and Johannes Zahlten. Cologne: Bohlau, 1991. Pp. 63-74.

WOLFE, CHARLES. The Devil’s Box: Masters of Southern Fiddling. Nashville, TN: Country Music Foundation Press; Vanderbilt University Press, 1997.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:30

Recorded: March-July, 1998 at WFMT Chicago

Producers: James Ginsburg & Sibbi Bernhardsson

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Production Assistant: David Dieckmann

Cover Photography: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Todd E. Sullivan

© 1998 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 041