| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

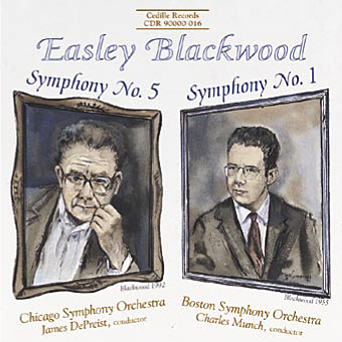

Easley Blackwood: Symphonies Nos. 5 & 1

Easley Blackwood, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra

The first orchestral recording that Cedille produced, this CD makes musical history on two counts by offering the premiere recording of American composer Easley Blackwood’s sumptuous new Fifth Symphony and the first-ever reissue of the landmark recording of his celebrated and strikingly original First Symphony.

Blackwood’s Symphony No. 1, Op. 3, was recorded by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra for RCA Victor in 1958 and released in 1959. Long out of print, the “Living Stereo” LP has become a prized collectors item. Cedille’s reissue was digitally remastered from RCA’s original stereo master tape, now part of BMG Classics’ archives.

The First Symphony’s premiere performances brought Blackwood praise as “a stoutly original musical thinker” (Time, November 24, 1958). Howard Taubman of The New York Times called him “a composer of uncommon gifts.” High Fidelity reviewer Alfred Frankenstein (February 1960) wrote of being captivated by “its freshness, its vitality, its dramatic, epical qualities, and the sense of a lively, original, uncompromising talent at work.” Hi-Fi/Stereo Review rated the performance and recording quality as “excellent” (March 1960). Eric Salzman, reviewing the recording for The New York Times (Jan 31, 1960), called the work a “wild, grandiose and eclectic work full of almost Lisztian gestures . . . this young composer wants his symphony to embrace and reconcile a whole world of varying musical materials.”

Blackwood’s Symphony No. 5, Op. 34, also reflects this abiding interest in a wide variety of musical styles, as well as Blackwood’s latter-day interest in tonal music and older harmonic idioms. Around the time Blackwood sat down to write the Fifth Symphony, he had become enamored of piano works by lesser-known modernists of the early 1900s. “I originally conceived the work as the kind of symphony Sibelius might have written had he experimented with the modernist techniques that attracted composers like Casella and Szymanowski,” Blackwood writes in the CD booklet.

The Fifth Symphony, completed in 1990, was commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to celebrate its centennial. Cedille’s recording is derived from the 1992 premiere concerts given by the CSO and conductor James DePreist.

Chicago Sun-Times critic Wynne Delacoma (May 22, 1992) heard “fingerprints of Sibelius and other late-Romantic era composers” in the symphony’s “spacious sweep and serene, unhurried melodies with hints of pastoral or folk elements.” Delacoma called the symphony “a well-crafted, graceful work” that achieved Blackwood’s twin goals of writing a work that orchestras enjoy playing and audiences enjoy hearing. “No one headed for the exits between movements,” Delacoma observed, contrasting the symphony’s enthusiastic reception with those that greeted other recent contemporary symphonic premieres.

Preview Excerpts

Symphony No. 5, Op. 34

Symphony No. 1, Op. 3

Artists

1: Chicago Symphony Orchestra / James DePreist

4: Boston Symphony Orchestra / Charles Munch

Program Notes

Download Album BookletEasley Blackwood: Symphonies Nos. 5 & 1

Notes by Easley Blackwood

I wrote my Symphony No. 5 in Chicago, completing it in September, 1990. During the composition period, I was very busy as pianist playing mostly chamber music (traditional and modern) written for unusual instrumental combinations. I also became very much taken with solo piano works by the less-known modernists of the teens and twenties, Alfredo Casella and Karol Szymanowski in particular. [Prof. Blackwood’s recording of piano music of those composers can be found on Cedille Records CDR 90000 003.]

The Symphony No. 5 is in three movements, and is clearly influenced by the stylistic diversity with which I was involved as a pianist. In fact, I originally conceived the work as the kind of symphony Sibelius might have written had he experimented with the modernist techniques that attracted composers like Casella and Szymanowski. The first movement is a conventional sonata form movement beginning in a modal version of B minor, with occasional impressionistic interludes where the tonality is not clearly defined. Quiet minor thirds often accompany the movement’s various motives. At times, the thirds are static; at others, they undulate slowly. About a minute in, the first trumpet introduces a five-note, chromatically descending fanfare — a motive which assumes greater significance as the movement progresses.

The second section is more conventionally tonal and features an expansive solo by the first horn. In the development section, dissonant and modal passages alternate, sometimes as chorales, sometimes as extensions of the fanfare motive. The original material returns in the recapitulation with slight variations, although the horn solo is unchanged (except for a transposition from D major to B major). In the coda, the undulating minor thirds return as an accompaniment for the initial theme and the fanfare. The movement concludes with an ironic variation on these two motives played by the English horn and bass clarinet.

The second movement begins with a quiet, sustained section, followed by expressive solos by the first clarinet, first oboe, and English horn. This leads to a more dissonant passage, featuring similar tunes played by the first flute, first trumpet, and first violins. Throughout this exposition, the thematic elements are melodies accompanied by slowly moving contrapuntal textures. Imbedded in the accompaniments are occasional discreet quotes of the first four notes of the liturgical sequence Dies Irae: F-E-F-D (several of these quotes had already worked their way into the counterpoint before I noticed).

The development consists of variations on the solos heard before. First strings and winds alternate in contrasting registers, then strings and brass alternate over a pedal point. In the recapitulation, the first two wind solos return, followed by a transition that leads to the climax of the movement. At this point, there is a surprising return to the original key of the movement (E-flat minor) as the Dies Irae fragment suddenly becomes the principal melody in the trumpets. The movement concludes quietly over an E-flat pedal point, with further references to the Dies Irae fragment.

The third movement serves as both a rondo and a scherzo. Although the movement is in B minor, there is no cadence until the thirty-sixth bar. This and the virtual absence of subdominant and dominant harmonies cause the rondo theme to have a slightly unsettled character in spite of its superficially jaunty mood. The first couplet (or “B” section of the rondo) is rather more dissonant, especially the passage that consists of rapid figurations in the winds over successions of chromatically related triads. After a brief reference to the rondo theme, material from the beginning of the first movement is recalled. Following a dissonant climax and a quieter interlude, the rondo theme recurs with an extended variation.

Much of the remainder of the movement continues the alterations of motives heard earlier in diverse variations. The initial theme of the first movement ultimately returns, however, this time on a triumphant note, along with the chromatically descending fanfare motive. After subsiding briefly, the piece closes unexpectedly with a fortissimo B minor triad.

I wrote my Symphony No. 1 in Paris, completing it in December, 1955. At that time I was studying both composition and keyboard reading skills with Nadia Boulanger. Paris in the 1950’s was a very stimulating place to be a composition student. Four different orchestras presented complete seasons, as did two opera companies. The city also boasted numerous chamber music concerts and solo recitals. During this period, I was active as a pianist, particularly as a Lieder accompanist going on extensive tours in France and Germany.

The Symphony No. 1 is a four-movement work in which material heard early on often recurs in various transformations in later movements. This characteristic seems very French indeed, if one examines the symphonies of Chausson, Franck, d’Indy, and Saint-Saëns — works which I have found attractive and ingenious since my days at Yale (1950-54). Elements found in the slow introduction give rise to the thematic cells of the body of the first movement. In these cells, however, the original thematic ideas are often transformed in character and presented in variations, some of which are canonic.

Structurally, this movement is in a modified sonata form; for example, the oboe solo that begins in A major clearly states a second theme. There is no true recapitulation, however, for the second theme is not recalled as first presented. The movement closes with a seven-note motive contained within a minor third. This motive, along with its dissonant harmonization, is drawn from the introduction.

The second movement contains two themes more alike in character than those of the first movement. These themes are juxtaposed and changed in register and harmonization in a variety of ways, including one episode in which the initial theme is played in canon. The initial theme ends with the same motive that closes the first movement, and the second movement also concludes with this motive.

The third movement is a scherzo and trio in which the recapitulation of the scherzo is followed by a coda. The first statement of the scherzo consists of four versions of the same eighteen-measure tune. This strain is first played alone, then repeated with increasingly intricate accompaniments. The trio is based on the same motive that has closed the previous movements. Here the motive undergoes several variations, including one that is canonic. At the end of the trio section, the two themes — scherzo and trio — are played simultaneously. The return of the scherzo presents the initial theme in a version shortened to seven measures, this time in six increasingly complex variations. The coda, like the trio, is based on the out lined minor third, which again is used to close the movement.

The last movement has a more rhapsodic character than the other three. It is, in large part, a variation on the first movement, but with the material transformed in character, along with interludes of elements that have not appeared before. Of special note is a recurring progression of two seventh chords (a major seventh followed by a half-diminished seventh) that assumes greater importance as the movement unfolds. Following the movement’s single climax, there is an epilogue based on the motive outlining a minor third that has closed each previous movement. This time, however, the motive is played in combination with the seventh-chord progression, which ends the piece by oscillating more and more quietly until it finally fades away.

While it is hardly possible for a composer to view his works with complete detachment, I cannot help but observe that these two symphonies, written thirty-five years apart, exhibit more than a little similarity (although it is certainly true that No. 5 is more conservative than No. 1). Similarities include the recalling of earlier material in later movements, juxtaposition of tonal and dissonant passages, frequent use of seventh chords in unconventional progressions, and similar traditional formal layouts.

The stylistic path that connects these two works is far from straight, however. When I began composing, in 1946, my style was very modern indeed — to the consternation of my teachers and counselors in Indianapolis. Shortly after 1950, a conservative trend sets in, lasting about ten years. In the 60’s and 70’s I evolved toward a more radical modernism. All the works I have written since 1980, by contrast, have been conservative; some have even been reactionary. For example, in a Sonata for Cello and Piano composed in 1986, I consciously attempted to employ a style that would have been idiomatic around 1845 [the Cello Sonata is available on Cedille Records CDR 90000 008]. At present, I feel “at home” in a wide variety of styles, and I doubt that my evolution will be any more constant than in the past.

Both symphonies heard on this disc were conceived as abstractions, intended as expressions of musical ideas solely. Of course, I do not deny that they create moods. For example, the slow movement of No. 5 certainly has a funereal aspect. But these works are not commentaries on social affairs; nor do they contain hidden political messages. They are intended to please listeners who enjoy classical music, and I hope they will be received in this light.

— Easley Blackwood

Album Details

Total Time: 57:46

Recorded: Tracks 1-3 recorded from live concerts, May & June 1992 at Orchestra Hall, Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Mitchell G. Heller for WFMT

Digital Editing: Bill Maylone.

Recorded: Tracks 4-7 made from master recordings owned by BMG Classics and recorded November 1958 at Symphony Hall, Boston

Producer: Richard Mohr

Engineer: Lewis Layton

Front Cover: Two watercolor portraits of Easley Blackwood by Jack Simmerling

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Easley Blackwood

© 1993 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 016