| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

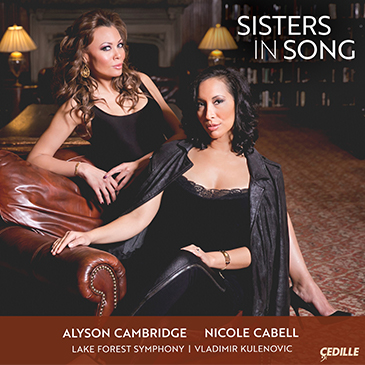

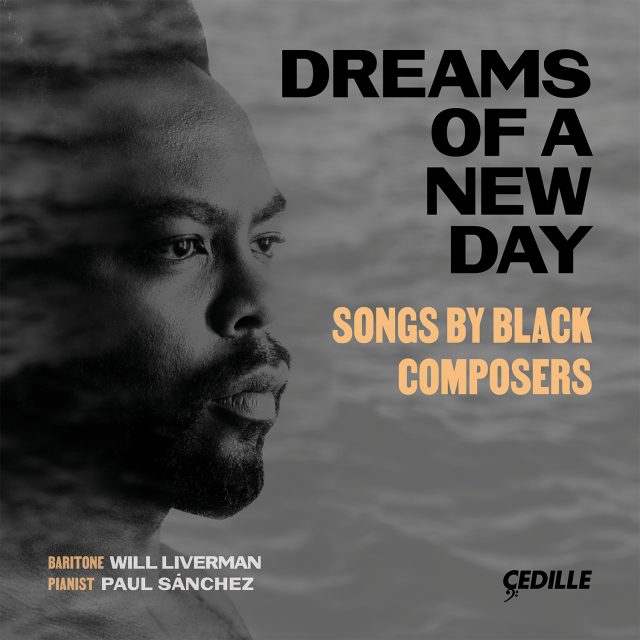

Dreams of a New Day — Songs by Black Composers

Paul Sánchez, Shawn E. Okpebholo, Margaret Bonds

2022 Grammy Nominee – Best Classical Solo Vocal Album

Fast-rising American operatic baritone Will Liverman, tapped for major roles at principal opera houses across the country, makes his Cedille Records debut as a featured artist with Dreams of a New Day, an intimate, heartfelt recital he calls “a passion project . . . years in the making.”

Praised for his “unique combination of eloquence and unpretentiousness” (Opera News), Liverman has assembled a program of songs that portray the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of the African American experience through poignant texts and expressive musical settings.

His new album, with pianist Paul Sánchez, highlights Black composers across generations, from early 20th-century pioneers Henry Burleigh, Margaret Bonds, and Thomas Kerr to Robert Owens, Leslie Adams, and contemporary composers Damien Sneed and Shawn E. Okpebholo.

Liverman commissioned Okpebholo’s Two Black Churches, which he recently performed to great acclaim at his Kennedy Center recital in conjunction with his winning the 2020 Marian Anderson Vocal Award. The Washington Post review called the set “absolutely devastating, and one of the most beautiful pieces of music I’ve heard all year.” This is its world-premiere recording.

“One of the most versatile singing artists performing today” (Bachtrack), Liverman concludes the album with his own powerful arrangement of American folk singer-songwriter Richard Fariña’s “Birmingham Sunday.”

This recording is made possible in part by generous support from Patricia A. Kenney and Gregory J. O’Leary and an anonymous donor

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Will Liverman on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

DAMIEN SNEED (b. 1979)

HENRY BURLEIGH (1866–1949)

Five Songs of Laurence Hope

LESLIE ADAMS (b. 1932)

MARGARET BONDS (1913–1972)

Three Dream Portraits

THOMAS KERR (1915–1988)

SHAWN E. OKPEBHOLO (b. 1981)

Two Black Churches

ROBERT OWENS (1925–2017)

Mortal Storm, Op. 29

RICHARD FARIÑA (1937–1966)

Artists

19: Arr. Will Liverman

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDreams of a New Day

Notes by Dr. Louise Toppin

African American art song narrates the journey — trials, tribulations and triumphs — of African Americans in the United States. These stories are preserved through a melding of poignant texts and expressive musical settings. Pairing the words of generations of poets and lyricists, who have encapsulated seminal events from the African American community, with rich musical textures amplifies these narratives. Unfortunately, this corpus of songs created by African Americans about the experience of Black Americans have long been deemed insignificant and relegated to a status of near invisibility. Will Liverman’s rich baritone voice in Dreams of a New Day is the perfect conduit to reveal this compelling history in song.

Many African American art songs have been inspired by the words of poets such as James Weldon Johnson, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Mari Evans, and Langston Hughes. Langston Hughes (1902–1967) was in fact one of the most eloquent writers to capture the African American essence during the Harlem Renaissance. His poem “I Dream a World” penned at the infancy of the Civil Rights era in 1941, articulates the urgent need for African Americans to gain peace and equality.

Damien Sneed (b. 1979) is a recording artist, pianist, organist, composer, conductor, arranger, producer, and arts educator whose work spans multiple genres, including the composition of several operas. A Sphinx Medal of Excellence recipient, he has worked with jazz, classical, pop, and R&B legends, including the late Aretha Franklin and Jessye Norman (he is featured on Norman’s final recording, Bound for the Promised Land). He has also worked with Wynton Marsalis, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, Ashford & Simpson, The Clark Sisters, J’Nai Bridges, and Lawrence Brownlee, among many others. A faculty member at the Manhattan School of Music, Sneed is a graduate of Howard University (Piano Performance), New York University (Film Scoring), and USC (Orchestral Conducting). Sneed created his 2017 setting of “I Dream a World” for the Carnegie Hall debut recital of Justin Michael Austin — a young baritone on an upward trajectory and current star at the Metropolitan Opera (much like Will Liverman). In addition to his operatic work, Austin uses his celebrity as a platform to address contemporary social issues. Sneed’s setting musically depicts the hope for the next generation with rich jazz harmonies, while ascending chords inch toward freedom on the line “where every man is free.” The final statement of the song, “I dream a world, my world,” leaves the listener with an unresolved final cadence that conveys a feeling of uncertainty.

Langston Hughes’s inspiration as a poet spanned several generations prior to Damien Sneed’s birth and served as a contemporary inspiration to Henry “Harry” Thacker Burleigh (1866–1949). In 1935, Burleigh created the final song in his large output of songs and set it to a text by Langston Hughes (“Lovely Dark and Lonely One”). This was the only time he used Hughes as his poet.

Originally from Erie, Pennsylvania, Burleigh began life singing in choir but also learning spirituals from his grandfather. Burleigh studied classical voice and became a well known singer around the city. For college, Burleigh attended the National Conservatory where Antonin Dvořák was the Director. Their interactions led to one of the most unlikely, yet powerful collaborations in American musical history. Dvořák, who heard Burleigh singing spirituals, learned more about this vernacular song from him. Furthermore, Dvořák encouraged Burleigh to use the wonderful source material of his people in his own composition. Burleigh, in turn, affirmed Dvořák’s exploration of Czech nationalism in his own writing at a time when Richard Wagner was the dominant compositional voice in Europe.

He began his compositional career by penning nearly 150 art songs to primarily non-Black poets. His songs, which seem devoid of racial identifiers, do incorporate two African American poets: James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes. His best known song for baritone is “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors,” to the poetry of Walt Whitman, which describes a riveting conversation between a Black woman and a soldier. Although several of his songs explore themes of exoticism, the majority explore different aspects of life, love, death, and joy. Each refreshingly original song is written with the dramatic and vocal scope of a quasi-operatic aria. Burleigh sang professionally throughout his career and his songs reveal his lifelong development as a formidable composer for the voice.

The Five Songs of Laurence Hope composed in 1915, were written to the poetry of Adela Florence Nicolson (1865–1904), who wrote under the pseudonym “Laurence Hope.” She was married to Colonel Malcolm Nicolson and lived much of her life in India and parts of the Middle East. Her poetry reflects her surroundings and some of them include imagery from this region of the world (Kashmiri, lotus flower, etc.). Her poetry reveals, autobiographically, the tumultuous relationships in her life. She suffered from mental health issues throughout her life and when her husband died suddenly, she consumed poison and committed suicide at the age of 39.

Burleigh did not forget Dvořák’s advice and explored spirituals in his compositional work, most notably in the second half of his career. He is therefore credited with being the first composer to create spirituals in an art song format for presentation in concert halls. Because Burleigh’s output included both art songs and spirituals, his work is an important initial thread connecting spirituals and African American art song composition.

The history of African American art song (music composed for the concert hall by African Americans) has its genesis in vernacular song and spirituals. The songs created by the enslaved Africans included the African practice of singing as an accompaniment to life’s events — work, play, celebration, and sorrow. For the enslaved Africans, who were from various parts of the continent and spoke different languages, song served as a unifier when they were forcibly brought to the United States. Songs, along with cultural norms, allowed the enslaved to create not only a new community but a new song style — the spiritual — that combined their African performance practice with the biblical stories of their enslavers. These songs, created during the institution of slavery in the United States, represent a uniquely American folk song.

Post-slavery (1865 and after), the spiritual was replaced by other burgeoning musical forms including blues, ragtime, and jazz as the new musical expression of African Americans. The spiritual was not completely abandoned, but was preserved using European notation to capture what had once been an oral tradition.

While the early versions are more literal arrangements of the spiritual, contemporary composers reimagine the use of this source material in new and exciting ways. For example, a composer might musically quote a fragment of a spiritual, show the structural contour of a spiritual, or even just use the title of a song to evoke the essence of a spiritual.

Burleigh is noted for the creation of art song spirituals for professional singers to use on concert stages. Although Will Liverman’s musical selections do not include any spirituals, all of the composers represented have been heavily influenced by them and they have either arranged or incorporated reimagined spirituals within their works. The selection of “Amazing Grace” pays homage to the period of enslavement and more specifically the Middle Passage (the established route that brought enslaved Africans to the United States and Caribbean). The song “Amazing Grace” is commonly mistaken for a spiritual, as it was composed at the height of the slave trade. It was not created by enslaved Africans, however. The song was a hymn penned by slave ship captain John Newton (1725–1807). Newton wrote his famous words after praying for deliverance during a storm at sea. His subsequent conversion from slave ship captain to abolitionist is underscored in the opening line, “A Mazing grace! (how sweet the sound) That sav’d a wretch like me!” This song has become a prayer for comfort in times of tribulation and is frequently heard at funerals. Most notably, President Obama chose to sing this song at the Mother Emmanuel Church service in response to the AME Church massacre.

Newton’s setting is not the only song featuring the words “Amazing Grace.” The same two words have been used as the opening text for at least three well-known songs. In 1967, gospel singer Dottie Rambo (1934–2008) penned the second song that references the concept and text of “Amazing Grace.” Using the tune of “O Danny Boy,” she added the words “Amazing grace will always be my song of praise.” This version is more peaceful and contemplative. While the first two versions strike a tone of penance, Harrison Leslie Adams’s “Amazing Grace,” written in 1992, bespeaks a gratitude that bubbles with exuberant energy and hope. His use of double octaves heavily accented in both hands, constant parallel motion, and colorful harmonic language simulates the ebb and flow of waves and represents the ebb and flow of life. Adams’s composition takes us on a journey that pays homage to the enslaved Africans of Newton’s version as he expresses optimism for a brighter future for African Americans.

Harrison Leslie Adams (b. 1932) is one of the most prolific composers of art song today. He has written more than 45 songs, plus piano, organ, choir, chamber, and orchestral works. He holds degrees from Oberlin College of Music, California State University, and a PhD from Ohio State University. While he has held several academic positions, he has worked as a freelance composer, based in Cleveland, Ohio, for several decades. His idiomatic vocal writing is masterful and well-crafted. His songs, which include several to texts of African American poets, are a complementary wedding of text to melody. His most popular include “For you there is no song,” “Sence you went away,” and the set Nightsongs that includes poems of Langston Hughes.

The transformational power of Langston Hughes’s words is apparent in the sheer number of musical settings of his poetry. His poems speak to and continue to inspire contemporary composers as much as they excited his contemporaries. One of Hughes’s favorite contemporary collaborators was Margaret Allison Bonds (1913–1972). She became acquainted with the poetry of Hughes in 1921 when she found his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in the public library while a student at Northwestern University. She felt his poetry expressed the isolation and racism she experienced during her undergraduate education there. A native of Chicago, Bonds and her mentor, Chicago transplant Florence Price (1887–1953), made history by winning the city’s famed Wanamaker competition. Not only did Bonds win first prize for one of her songs, but she also became the first African American to perform with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (playing John Alden Carpenter’s Concertino for Piano and Orchestra in 1933). Throughout her career, she worked fervently to provide music instruction for African American youth. She also curated concert opportunities that allowed African American artists and composers to showcase their talents to New York audiences.

Many of her songs reflect pride in her race, including the Three Dream Portraits written to texts of Langston Hughes in 1959 for two prominent African American opera singers: Adele Addison and Lawrence Winters. Addison and Winters were unable to premiere the songs; they were instead premiered by Lawrence Watson at a National Association of Negro Musicians concert in Ohio in 1959. Written at the height of the civil rights movement, they express the Black pride that became a hallmark of the blossoming Black Arts movement. “Minstrel Man” describes the invisibility African Americans felt in a society that ignored them and lacked the compassion to know them as people. “Dream Variation” describes the desire for unhindered freedom with the text “To fling my arms wide in the face of the sun, Dance! Whirl! Whirl till the quick day is done.” The final lines describe the peaceful end of day and the welcome calm of night with the line “night coming tenderly, black like me.” The final poem, “I, Too,” was written as a response to Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing.” Whitman’s poem describes the life of hardworking Americans. Hughes, however, felt that within the description, the experiences of African Americans were blatantly absent from Whitman’s depiction. Hughes’s poem begins “I, too sing America. I am the darker brother.” It goes on to say that, although removed from sight (a return to the first song’s theme of invisibility), the narrator will continue to gain strength, and with that strength push for a future of equality for all Americans.

In much the same way that Langston Hughes was heralded as the voice of his generation, 19th-century African Americans celebrated Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906) as their poet. Dunbar, who was from Kentucky, wrote poetry and stories depicting the oppression of African Americans during the Jim Crow era. Noted as the first African American poet to achieve international fame, his poems were crafted to depict a three-dimensional view of African Americans. Black Americans navigated two distinct cultures, meaning they simultaneously assimilated into the white world while they strove to retain their Black culture. That duality is reflected in his clever use of both “dialect” and “standard” English in his poetic narratives. As with Hughes, his authentic poetic voice has continued to inspire contemporary composers to produce new musical settings.

Much of his poetry that has been crafted into song is from an 1896 collection titled Lyrics of Lowly Life. Included in this collection, “Riding to Town” describes the delight of a loving pair as they journey together into town. Neither the destination nor the comfort of the vehicle is as important as the precious quality time they spend together. This peaceful moment allows them to dream and forget all the cares of the world.

Thomas Kerr (1915–1988), the composer of “Riding to Town” (written in 1943), was born in Baltimore a few years after Dunbar died. A pianist and organist, he graduated from the Eastman School of Music with three degrees in piano and composition. His musical output included solo voice, piano, instrumental, and choral works. He was Professor and Chair of the Piano Department at Howard University, where his work as a composer and teacher influenced generations of music students. Although the poetry of Dunbar and Hughes and those in other literary movements are important sources of inspiration for African American art song, they are not the only ones. Seminal events that defined and shaped the African American community serve as the source for powerful narratives that express the pathos, pain, and raw emotion of the community. And these have also been captured in song. The assassination of political leaders such as John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. have been demarked in oratorios and operatic works. Horrific events such as the lynchings of African Americans, the Birmingham 16th Street Church bombing, the Mother Emmanuel AME Church massacre, and other such atrocities have been preserved in vocal music. Two Black Churches (written in 2020), which chronicles two painful events for African Americans, was commissioned by Will Liverman. In the words of the composer, Shawn E. Okpebholo:

This work is a musical reflection of two significant and tragic events, each perpetrated at the hands of white supremacists in two black churches, five decades apart:

• The 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama which took the lives of four girls.

• The 2015 Mother Emanuel AME Church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, resulting in the deaths of nine parishioners.

The text of the first movement is a poem by Dudley Randall, Ballad of Birmingham, a narrative account of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing from the perspectives of the mother of one victim and her child. Stylistically, this movement juxtaposes 1960s Black gospel with contemporary art song. Subtle references to the civil rights anthem, We Shall Overcome, and the hymn, Amazing Grace, are also heard (in the piano accompaniment). The song concludes with four sustained soft chords resembling church bells. Each of the chords is comprised of four notes that punctuate and amplify the four young lives lost.

The text of the second movement is a poem written especially for this composition by Marcus Amaker, poet laureate of Charleston, South Carolina, called The Rain. This poem poignantly reflects the shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church. Set in the coastal city of Charleston, which often floods, The Rain is a beautifully haunting metaphor on racism and the inability of Blacks in America to stay above water — a consequence of the flood of injustice and the weight of oppression. In this composition, the number nine is significant, symbolizing the nine people who perished that day. Musically, this is most evident through meter and a reoccurring nine-chord harmonic progression. The hymn, ‘Tis so Sweet to Trust in Jesus, is quoted in this movement. This hymn was sung at the first service in the church after the shooting, testifying to a community that chose faith and hope over hate and fear.

Shawn E. Okpebholo (b. 1981) is Professor of Music Composition at Wheaton College-Conservatory of Music and a widely sought-after and award-winning composer, most recently winning the American Prize in Composition (2020). His music has been characterized as having “enormous grace… fantasy, and color” as he comfortably composes in various styles and genres. Much of his musical education as a child was from The Salvation Army Church where he received free music lessons. His experience with the Salvation Army shaped his passion for paying kindness forward through music education in underserved communities. Okpebholo’s music has been performed on five continents, in over 40 states, and in nearly every major U.S. city. He regularly receives commissions from celebrated soloists, chamber groups, and large ensembles — artists who have performed his works in some of the nation’s most prestigious performance spaces, including Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center. He earned his masters and doctoral degrees in composition from the University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music. In 2021, he will begin a two-year residency as Chicago Opera Theater’s newest Vanguard Emerging Opera Composer.

In the hands of a poet, tragic events can be translated into expressions of darkness, despair, and hopelessness. Langston Hughes’s output includes poems describing the agony and pain he felt in an extremely dark period in African American history (1920s–1950s). This is the period when African Americans grappled with a racist society that allowed its citizens to be terrorized by tightened Jim Crow laws; the random lynching of African Americans; massacres such as the Red Summer of 1919 and the Tulsa massacre in 1921; and race riots in which African Americans were beaten, killed, and bombed, and found no protection from those in authority.

It is no wonder that some of the poems Hughes penned during these years presented a more pessimistic view of African American life. Composer Robert Owens selected poems representative of a dark time in Hughes’s life to tell the story of a dark time in his own personal history (the Civil Rights era and Martin Luther King’s assassination). Using poems from the 1920s (“A House in Taos”), 1930s (“Genius Child”), and 1940s (“Little Song,” “Jamie,” and “Faithful One”), he created the song cycle Mortal Storm, Op. 29 in 1969. Particularly striking in this group is “Genius Child.” In this poem, Hughes speaks about killing the genius child so that his spirit may run free. Owens chooses a driving triplet figure to illustrate a terrifying scene that pauses only momentarily on the menacing line “nobody loves a genius child” and resumes with an outburst on the text “kill him.” When asked about this cycle in a 2007 interview with Dr. Jaime Reimer, Owens stated: “Mortal Storm tells the stories of ‘the storms we as mortals face.’”

Growing up in Denison, Texas, Robert Owens (1925–2017) faced his own “storms” of racism. As a result of this racial tension, he left the United States in 1968 to pursue opportunities in Germany and never returned to live in the U.S. He made his career in Germany as a pianist, composer, actor, and director. He, like H. Leslie Adams, was a prolific composer of art song and has an output of several song cycles for coloratura soprano, soprano, mezzo soprano, countertenor, tenor, baritone, and bass, written both in German and in English.

The “Genius Child” of Hughes’s poem speaks not only of the many men and women killed by lynching, or of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., but also of the lost promise of those four children in Alabama murdered in the 1963 bombing in Birmingham.

“Birmingham Sunday” is a song written by Richard Fariña (1937–1966) in 1964 to memorialize the bombing in 1963 of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins, and Cynthia Wesley. The melody is borrowed from the Scottish folk tune “I Loved a Lass” (aka “The False Bride”). The piece was first performed by Farina and his sister-in-law, Joan Baez. More recently, Spike Lee used the piece as the theme song for his 1997 documentary, Four Little Girls.

Will Liverman’s arrangement serves as a fitting final tribute to the struggles of African Americans. It indicates past and present injustices and provides an opportunity to refocus and reframe the American promise of equality for all its citizens. While making for a poignant and powerful conclusion to this musical offering it also serves as a reminder that the struggle against racism in America has not concluded but is very much a present struggle.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Graphic Design Bark Design

Cover Photo Jaclyn Simpson

Recorded

July 22–24, 2020, Sauder Concert Hall Goshen College, Indiana

Publishers

I Dream a Word © 2017 LeChateau Arts

Five Songs of Laurence Hope © 1915 G. Ricordi & Co.

Amazing Grace © 1992 Henry Carl Music

Three Dream Portraits © 1959 G. Ricordi & Co.

Riding to Town © 1977 Thomas H. Kerr, Jr.

Two Black Churches © 2020 Yellow Einstein Press

Mortal Storm © 1969 Orlando-Musikverlag

CEDILLE RECORDS © 2021

CDR 90000 200