| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

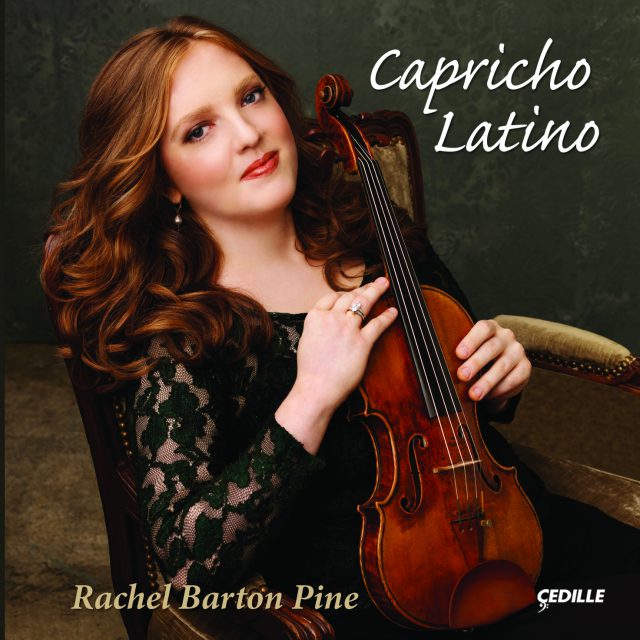

Violinist Rachel Barton Pine, Cedille Records’ all-time best-selling artist, has created another rare – perhaps unique – contribution to the world’s CD catalog: an album of Spanish and Latin American music written solely for unaccompanied violin. Capricho Latino, Ms. Pine’s 12th Cedille CD, offers eight world-premiere recordings: In addition to premieres of works by Roque Cordero, César Espejo, and José White, the CD brings first-time recordings of pieces composed or arranged for Ms. Pine by José Serebrier, Luis Jorge González, and Jesús Florido; and two of her own arrangements. The diverse program of virtuoso pieces draws from the late-Romantic period to the present day. Represented are composers from Argentina, Cuba, Panama, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela – plus works in a Spanish vein by Belgian and English composers. Inaugurating this musical journey is Ms. Pine’s virtuoso arrangement of Albéniz’s Asturias, which draws on both the familiar guitar version and the original but less-known piano score. The CD ends with a treat for listeners of all ages: Alan Ridout’s Ferdinand the Bull, narrated with great affection by Obie and Emmy award winning actor Héctor Elizondo, a veteran of Broadway, Hollywood, and network television.

Preview Excerpts

ISAAC ALBÉNIZ (1860-1909) arr. RACHEL BARTON PINE

ROQUE CORDERO (1917-2008)

TRAD (arr. Jesus Florido)

CÉSAR ESPEJO (1892-1988)

MANUEL QUIROGA (1892-1961)

EUGÈNE YSAŸE (1858-1931)

LUIS JORGE GONZÁLEZ (b. 1936)

JOSÉ WHITE (1835-1918)

FRANCISCO TÁRREGA (1852-1909) arr. RUGGIERO RICCI

JOAQUÍN RODRIGO (1901-1999)

JOSÉ SEREBRIER (b. 1938)

ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (1921-1992) arr. RACHEL BARTON PINE

ALAN RIDOUT (1934-1996)

Artists

3: Traditional arr. JESÚS FLORIDO

6: MANUEL QUIROGA

14: with Héctor Elizondo, narrator

Program Notes

Download Album BookletCapricho Latino

Notes by Elbio Barilari

Asturias is the name of a northern region of Spain with a strong local character. Its inhabitants speak Asturian as well as Spanish and have a distinct musical tradition. Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909), a Catalonian composer, included this tribute to Asturias as a part of his Chants d’Espagne (Melodies of Spain) a series of pieces he started writing in 1883.

Asturias is probably the best-known piece of Spanish classical music. (It is often called Leyenda (Legend), a subtitle added to Asturias in 1911, when the German company Hofmeister published the first complete version of Albeniz’s Suite Española.) Together with Mozart’s 40th Symphony and Vivaldi’s Spring, it belongs to that select company of melodies that people whistle in the streets from Madrid to Buenos Aires. At first, Albéniz gave his piece the unobtrusive title Preludio; he wrote it for his principal medium, the piano. Albéniz was one of Europe’s most vaunted pianists and his catalogue includes many major piano works, foremost among them the monumental suite Iberia.

The global popularity of Asturias began when Albéniz’s fellow-composer Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909) made a transcription for the guitar. The tremolo device – repeated fast notes on one or more strings – is commonly associated with the mandolin; but in 19th-century Spain, the technique was adapted for the guitar, and Tárrega was one of its masters. Indeed, many popular compositions for guitar (including two on this CD) owe their appeal to this technically challenging, highly emotional expressive device.

In her introduction to “The Rachel Barton Pine Collection” (Carl Fischer, 2009), Rachel Barton Pine wrote about her arrangement of Asturias:

I drew upon elements from both the piano and guitar versions for this arrangement. In measures 62-64, I borrow a two-octave pizzicato technique from Bartók’s Sonata for Solo Violin to imitate the plucking of the guitar, while in mm. 103-04, I use the violin’s capability for legato as a way to increase the expressiveness. Occasionally, I have taken small liberties that I feel capture the spirit, though not the exact notes or rhythms, of the original; for example, the arpeggio runs in mm. 98 and 110. My hope when performing Asturias is to pay homage to the sound of the guitar while embracing its new life as a piece for the violin.

Roque Cordero (1917-2008), author of Rapsodia Panameña, is the most important name in classical music from his home country of Panamá. His catalogue includes a dozen major symphonic works, several chamber pieces for different ensembles, choral and piano music. He studied composition with Ernst Krenek and conducting with Dimitri Mitropoulos, among others. His pieces, linked to the 20th century avant-garde style and often based on the twelve-tone system, have been widely performed.

Maestro Cordero was one of the first and very few who tried to link the European dodecaphonic and serial languages with Latin American themes and roots. He developed strong associations in the U.S., where he was assistant director of the Latin American Music Center at Indiana University (Bloomington) and professor emeritus at Illinois State University. The Detroit Symphony, Louisville Orchestra, and Chicago Sinfonietta have all recorded his works. (Cordero’s Eight Miniatures for Small Orchestra appears on Cedille Records’ African Heritage Symphonic Series, Vol. 2, featuring the Chicago Sinfonietta conducted by Paul Freeman.)

Rachel Barton Pine writes:

I first learned Roque Cordero’s violin concerto in 1999 when I performed it with the Chicago Sinfonietta. I asked for his other violin works, and when I came to Dayton, Ohio, to solo with the Philharmonic a few years later, we worked on Rapsodia Panameña together. I performed his concerto again in 2009 in Dayton in a concert that sadly became a memorial celebration. In summer 2010, I gave the Panamá premiere of the concerto at the Alfredo Saint-Malo Music Festival and also performed the Rapsodia. Cordero told me that the gentle main theme that begins in measure four was based on music of the indigenous people of Panamá. I love how this work goes back and forth between Latin rhythms and melodies and 12-tone music while remaining coherent.

Balada Española (Romance) is another fantastically popular piece among guitar players, both professional and amateur. A 1952 French movie, Forbidden Games (Jeux interdits), which used the melody, is in part responsible for its widespread fame, to the point that the piece itself is often called by the movie’s title. Narciso Yepes (1927-1997), the well-known Spanish guitarist, claimed to have composed it – as a young boy, he said – but when it came to light that Romance had been published before his birth, and that a cylinder recording had been made around 1900, an air of scandal attached to the claim. Nonetheless, in many guitar books, the credit still appears as “Traditional, arr. Narciso Yepes.”

Happily, there are no outlandish claims associated with the present version for solo violin: Venezuelan-born violinist Jesús Florido (b. 1969) created his arrangement expressly for this CD. In Romance, the central feature is not the tremolo but the permanent arpeggio, which creates both the melody and the feeling of moto perpetuo (perpetual movement) that renders the music so enchanting. Arpeggios are a very guitar-like effect, one of the most natural and comfortable things a guitar can do; but this is not quite so for the violin. When one bow needs to do the job of four fingers, the knowledge of the arranger and the skills of the performer are put to the test. Pine’s delightful recording will expand, no doubt, the fan-base of this traditional hit.

César Espejo (or Espéjo, in the French spelling) was born in Málaga, Spain, in 1892, son of the Spaniard Amador Espejo and the renowned French piano and organ teacher Elisa Boucherant. His entire musical career unfolded in France, where he played violin and conducted numerous orchestras, including those of the National Opera and the Théatre Mogador in Paris. He composed more than fifty pieces, most for the violin; his book of scales for the instrument is still in print. Despite his lifelong residence in France, Espejo never lost his Spanish identity or his taste for Spanish music. In posterity he has suffered a notable, and notably unjust, obscurity. He died in France in 1988.

In his Prélude Ibérique, dedicated to the towering violin virtuoso of his time, Henryk Szeryng (1918-1988), Espejo shows himself to be in total command of the Spanish idiom developed since the second half of the 19th century by his predecessors and contemporaries Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados (1867-1916), Manuel de Falla (1876-1946), and Joaquín Turina (1882-1949).

In this work, which is otherwise a perfect and powerful malagueña – a dance from Málaga whose best-known example comes from Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona (1895-1963) – Espejo gracefully incorporates the whole-tone scale without compromising the music’s Spanish character. This is serious virtuoso writing for solo violin. Espejo’s original solo version and a second score with ad libitum piano accompaniment were both published in 1958. Another piece by Espejo, Air Tziganes, was recorded by the no less emblematic Mischa Elman in the 1950’s (Elman Plays Hebrew Melodies, Vanguard Classics).

Rachel Barton Pine has expressed curiosity about whether Henryk Szeryng knew of this piece dedicated to him and whether he ever played it. Szeryng never recorded this Prélude but, given Espejo’s presence at the center of the European musical scene of the time, it is fairly safe to assume the great violinist knew of the work.

Espejo also dedicated a violin piece, Fileuse Op. 12, to fellow violinist Manuel Quiroga, who happens to be our next composer.

Manuel Quiroga (1892-1961) was a violin hero cut from the same cloth as his idols Fritz Kreisler and Pablo de Sarasate. During his youthful, triumphant, and short-lived career as a virtuoso he was often compared to the latter but shared a destiny with the former: like Kreisler, Quiroga was struck by a vehicle while walking in New York City. The 1932 accident brought his career as a violinist to an early end. By that time he was considered one of the world’s leading violin virtuosos; he was touring extensively in Europe, the U.S., and Latin America, often in duo with pianist José Iturbi, recording, and winning praise from audiences and critics. He was also admired by his peers including Kreisler, George Enescu, Jascha Heifetz, and Eugène Ysaÿe, who dedicated to Quiroga his Sonata No 6, also included on this CD.

There are many ways of being a Spaniard: Andalusian, Catalonian, Valencian, Basque, Asturian, or Gypsy, among others. Manuel Quiroga was Galician. Galicia is the northwestern region of the peninsula, with a Celtic provenance and its own language, Galician or gallego. Both as a composer and a well-respected painter, the multifaceted Quiroga strove to represent his regional identity. Although composed in Paris, in 1924, both Quiroga pieces on this CD bear titles or subtitles in gallego.

Emigrantes Celtas (Celtic Immigrants) is a fantasy for solo violin based on the famous Galician folk theme Lonxe d’a terriña … Lonxe d’ó meu Lar (Far away from my Motherland . . . Far away from Home). It presents an alternation of 3/4 and 4/4 meters very typical of that region and a distinctive nostalgic feeling Galicians call morriña.

Terra!! Á Nosa!! (Land!! Our Land!!) is based on a popular muñeira or folkloric Galician dance. It is in 6/8 time and presents the use of drones, or pedal-notes, to imitate the sound of the gaita (bagpipe), the most characteristic instrument in Galician music.

Quiroga’s many-sided artistry has been recovered in recent years through celebrations, scholarly papers, exhibits, and concerts, especially (but not only) in his homeland of Galicia. Ramón del Valle-Inclán, one of Spain’s major poets and also a gallego, dedicated to Quiroga a poem titled ¡Del Celta es la Victoria! (The Celt is the Victor!).

A substantial portion of this CD is devoted to music by a tight-knit élite of early 20th-century violinist-composers revolving around the Belgian master Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931). Ysaÿe, whose importance has increasingly been recognized in recent years, dedicated his Sonata No 6 to his friend Manuel Quiroga; César Espejo also dedicated a piece to Quiroga. Closing the circle, Quiroga exchanged dedications with Uruguayan composer Eduardo Fabini, who was, at that time, the violist of the celebrated Ysaÿe String Quartet, with which Quiroga frequently played. This circle of Spanish and Latin American musicians – including the elder José White, another composer on this disc – brought to the European scene a Latino “touch” entirely recognizable in Ysaÿe’s Sonata No 6, also known as his “Spanish Caprice.”

The Habanera pattern – dotted eighth-note, sixteenth-note, and two eighth-notes, made famous by Bizet’s Carmen – is probably not from Havana, and was certainly not invented by Bizet. Together with the clave, the Habanera’s bass motif is one of the most characteristic rhythmic patterns in African-influenced Latin American music. Master composer that he was, Ysaÿe knew how to mask the Habanera for the first 106 bars of his piece, and then abandon it after making clear that, yes, this is a Habanera after all – a very subtle and demanding Habanera that fulfills to perfection the Latino spirit of this recording.

Tango is neither Argentine nor Uruguayan. Tango is urban music, the music of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, twin cities facing each other across the Río de la Plata, where this genre was born around the 1880’s. Epitalamio is a Greek form of lyric poetry, later imitated by the Romans, for wedding ceremonies. It was usually sung by a choir of young men and maidens, to the accompaniment of flutes, at the door of the nuptial room.

Luis Jorge González (b. San Juan, Argentina, 1936) writes:

Epitalamio Tanguero is dedicated to Rachel Barton and Greg Pine, and was composed as a wedding present. The piece was written with some distinctive elements in mind: Rachel Barton’s outstanding virtuosity and unique expressiveness, and the passion and typical crossed accents of the best known dance of my native country. The musical language is freely tonal. These features were articulated in a free sonata form without the traditional development and it has a brief coda.

González is the author of an impressive body of orchestral, chamber, and vocal music. A Guggenheim Fellow and winner of the Radio France International Guitar Competition, his works have been performed across the world. González has taught theory at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore and theory and composition at the National University of San Juan, Argentina. Since 1982, he has been a faculty member at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Rachel Barton Pine writes:

Luis Jorge González and I first met in 1999 when I performed the Alban Berg Violin Concerto at the Colorado Music Festival in Boulder. My encore that evening was the Last Rose of Summer Variations by Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst. Luis gave me a copy of an unaccompanied tango-flavored piece he had recently written, Faust’s Serenade. A few years later I returned to Colorado and worked on it with him, and subsequently became the first violinist to perform it. Epitalamio Tanguero was a surprise wedding present in 2004. Luis told me that he remembered my performance of the Last Rose when writing it, and indeed it demands many of the same technical feats as the Ernst piece, such as simultaneous bowing and pizzicato, and a devilishly difficult section of arpeggios with an embedded melody.

The son of a French father and an Afro-Cuban mother, José White – violinist, composer and conductor – was born in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1836, and died in Paris in 1918. A noted child prodigy, nobody in his country was surprised when, in 1856, he won first prize at the Paris Conservatoire, then the world’s musical mecca. There he studied with the revered French violinist Jean-Delphin Alard. (Pablo de Sarasate was his classmate.) Performing on a 1737 Stradivarius named “The Swan’s Song,” White traveled the world as a violin virtuoso, often in the company of another eccentric talent, American pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk. At the Conservatoire, White gave lessons to such future stars as Enescu and Jacques Thibaud, and was a regular member of the jury for the Conservatoire’s graduation exams.

Adored by audiences and critics alike, enjoying the adulation of the musical élite and European aristocrats, White did not forget his native country. He composed several pieces inspired by Cuban music and enraged the Spanish colonial authorities with his vigorous support of Cuban independence, for which they banned him from returning to the island. The founder of modern Cuba, José Martí, once commented: “White doesn’t play, he subjugates [the violin to his will].”

As a composer, José White followed two tendencies: the romantic mainstream, as in his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in F-Sharp Minor (recorded by Rachel Barton Pine and the Encore Chamber Orchestra on Cedille Records’ Violin Concertos by Black Composers of the 18th and 19th Centuries), and popular Cuban music, as in his beloved La Bella Cubana.

Each of White’s Six Etudes (1868) is dedicated to a famous violinist: his teacher Alard, Ernesto Camillo Sivori, Henri Vieuxtemps, Henryk Wieniawski, Hubert Léonard, and one Secundino Arango, whose identity has intrigued European and American scholars. Arango, Afro-Cuban, born in Havana at the end of the 18th century and deceased in the same city in the late 1840’s, was a violinist, cellist, organist, and composer of both religious music and popular danzones. He was also White’s first violin teacher. Fittingly, White’s Etude No. 6 is a danzón with a pyrotechnic central section much in the virtuoso Parisian style of the time.

Recuerdos de la Alhambra (Memories of Alhambra), by Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909), is the one piece that might rival Asturias‘s popularity among classical guitarists. And since the guitar version of Asturias is a co-creation of Tárrega’s, it is not un-reasonable to call Tárrega the most popular classical guitar composer ever.

Tárrega is considered the founder of modern technique for the classical guitar. He was fascinated by the Arabic legacy in Spain; besides Recuerdos de la Alhambra, which depicts the resplendent Moorish palace in Granada, he wrote other Arabian-inspired pieces, notably Capricho Árabe and Danza Mora. He also transcribed for guitar many keyboard compositions by Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Albéniz, and other composers, thereby helping to establish the guitar as a classical instrument.

Recuerdos de la Alhambra, written in 1896, uses the tremolo technique to reproduce the hypnotic quality of Arabic music. Italian violinist Ruggiero Ricci (b. 1918) made the transcription for violin that Rachel Barton Pine performs on this recording. She comments:

In Ruggiero Ricci’s arrangement, he indicates that the bowing from Paganini’s Caprice No. 5 (three bounced down-bows followed by an up-bow) is to be used throughout. This particular technique, considered one of the most challenging in existence, is actually a specialty of mine, but I didn’t feel that it best served the music. In my opinion, the legato approach that I take lends itself better to bringing out the sustained melody notes.

Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999) is often seen as a one-piece composer (Concierto de Aranjuez) or a one-instrument composer (guitar). Yet despite the formidable popularity of Aranjuez (1939) and its sequel, Fantasía para un Gentilhombre (1954), guitar music makes up less than half of Rodrigo’s catalogue.

Composed in 1944, Rodrigo’s violin Capriccio (Offrande à Sarasate) was premiered in Madrid in 1946 by the Spanish virtuoso Enrique Iniesta, who two years before had premiered Rodrigo’s Concierto de Estío for violin and orchestra. The Capriccio is a very demanding piece in which the violinist is asked to do unusual things, well beyond double- and triple-stops and other virtuosic devices common in the language of the dedicatee, the Spanish virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate.

Why would Rodrigo write so difficult a piece for the violin? On the one hand, he seems to be trying to expand the technical possibilities of the violin as he did with the guitar. It is worth noting, however, that Rodrigo was blind. He lost his sight at the age of three after contracting diphtheria. Rodrigo wrote his music in the Braille system and his scores needed to be transcribed in order to be performed. Whatever the reason, and as difficult as his violin writing might be, the musical results are thrilling when performed by a true virtuosa, as on this recording.

José Serebrier (b. 1938) is a Uruguayan-born composer and conductor with an extensive international career. At age twelve, he conducted his first concert; at 15, he won his first conducting composition. When he was 17, his first symphony was premiered by Leopold Stokowski. Serebrier studied composition with Martinu and Copland, among others. His ground-breaking recording of Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 4 is a landmark in the performance of American music. As a composer, his catalogue includes several award-winning symphonic and chamber pieces. In 2004, he won the Grammy award for “Best Classical Album” for his Carmen Symphony.

Rachel Barton Pine relates:

Maestro Serebrier and I first met when we were both on the jury of the Sphinx Competition. We have subsequently collaborated with orchestras around the world and have worked on two albums together: Beethoven and Clement Violin Concertos with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra for Cedille Records and Serebrier’s Glazunov Complete Concertos with the Russian National Orchestra for Warner Classics, for which I recorded Glazunov’s Méditation in D major for violin and orchestra, Op. 32, and Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 82. A couple years ago, he showed me a little tango-style piece that he had written for violin and piano. I liked it so much that I commissioned him to write an unaccompanied tango-inspired work specifically for this album project.

In his Aires de Tango (Tango Airs), written in 2010, Serebrier evokes with total freedom the ultra-romantic violin solos practiced throughout tango’s history by such icons as Julio De Caro, Alfredo Gobbi, Enrique Mario Francini, Elvino Vardaro, and Antonio Agri. In tango slang, that highly romantic solo style is called tocar gitano (to play Gypsy) in contrast to the marcato rhythms that Serebrier also utilizes. The Uruguayan maestro chooses a highly chromatic language that coheres with tango music as practiced from the 1940’s on. Aires de Tango, an intense reminiscence crystallized as an abstraction, sets the bar very high for future composers of tango-inspired contemporary music.

Serebrier writes:

Aires de Tango, my most recent work for solo string instrument, was commissioned by Rachel Barton Pine for inclusion in her recording of short works for solo violin for Cedille Records. Having just recorded with her and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (also for Cedille) the Beethoven concerto and the world premiere recording of the Franz Clement concerto, the idea was most appealing. I was delighted to accept the invitation, and I am equally delighted to dedicate the work to her.

My two previous tango-inspired pieces, Tango in Blue and Almost a Tango, and finishing/orchestrating Satie’s Tango Perpétuel, had prepared me for this new assignment. Here was an opportunity to do a virtuoso essay with the spirit of the tango as the inspiration: not an obvious tango, but a work that evokes the perfume of the genre, the feel and color of the tango, its nostalgia, sadness, bitterness.

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) is the best-known founder, though not the only one, of what is called the new tango. Piazzolla composed Libertango (Freedom Tango), to lyrics by the Uruguayan poet Horacio Arturo Ferrer, in 1990, while the composer was living in Italy. Originally conceived for bandoneón (a type of concertina) and a dense instrumental group, the piece has found life in a variety of settings. Rachel Barton Pine gave a good deal of thought in distilling the piece to its very essence:

I created this arrangement specifically for this album project. Piazzolla never wrote anything for unaccompanied violin, or for violin and piano, to my knowledge. Violinists have therefore had to resort to playing his pieces for unaccompanied flute, the Six Tango Etudes. The published music says “For Flute (or Violin).” However, those pieces are clearly defined by the flute, having a smaller range, slurring and figurations idiomatic for a wind instrument, and no double-stops or chords. I decided to take my favorite Tango Étude, No. 3, and rethink how it might have been written if Piazzolla had had the violin in mind. In order to do this, I spent a lot of time studying recordings of Piazzolla’s own band and listening carefully to the playing of his violinists. Realizing that the popular Libertango was in the same key and tempo as Tango Etude No. 3, I decided to make a medley, again drawing my ideas from Piazzolla’s performances as well as being inspired by the playing of numerous tango violinists who have recorded Libertango. I really wanted to include a bit of the chicharra [cicada], the special tango technique of scrunching the bow behind the bridge, but it didn’t seem to fit anywhere in the arrangement, so I finally added a little introduction and included it there. As a longtime fanatic of Piazzolla’s music, I feel comfortable saying Astor would have been more than pleased.

In 1938, as Spain was being ravaged by civil war, Walt Disney produced a cartoon that would cause riots and conflagrations across Europe. Ferdinand the Bull – the story of a gentle animal who would rather smell flowers than fight in the bullring – won an Oscar in the cartoon category. But its tender story did not touch the hearts of armies that were trying to install a fascist regime in the land of Don Quixote. Partisans of General Franco called the story an insult to Spain. They burned copies of the original book in the squares of several towns while Hitler’s commanders, who had sent troops to fight alongside Franco’s, condemned the book as pacifist propaganda and had it burned in German streets.

Undoubtedly, this children’s story by American writer Munro Leaf (1905-1976) had hit a nerve. The cartoon was a pure Hollywood mishmash, portraying Mexico and Spain as the same country, showing young bulls head-butting each other (which they do not do), and so on. Same went for the cartoon’s lively musical score, presenting flamenco guitars intertwined with Mayan marimbas, stereotypical castanets, and mariachi trumpets.

Nevertheless, Ferdinand the Bull is hugely beloved and, since its creation, has never been out of the public eye. British composer Alan Ridout (1934-1996) was inspired, three decades later, to write a new and beautiful score for the story which he published in 1971. Ridout was a prolific composer of symphonic, choral, and chamber works within the tonal tradition. His Ferdinand, written for narrator and violin, follows the plot and reflects the action with delicacy, subtlety, and humor.

Uruguayan-born composer and writer Elbio Barilari lives in Chicago. His music has been performed at Millennium Park’s Pritzker Pavilion, the Ravinia Festival, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Symphony Center. He has received commissions from the Grant Park Music Festival, Ravinia Festival, Chicago Children’s Choir, Concertante di Chicago, and numerous chamber ensembles. Currently, he teaches Latin American Music at the University of Illinois at Chicago and hosts the weekly radio show Fiesta! on Chicago classical station WFMT.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:38

Producer: Judith Sherman

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: July 13-15 and 17-18, 2009, and January 6, 2011, in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago, IL

Violin: “ex-Soldat” Guarneri del Gesu, Cremona, 1742

Strings: Vision Titanium Solo by Thomastik-Infeld

Bow: Dominique Peccatte

Style Director: Jesús Florido

Narration Recorded: December 8, 2010, at DG Entertainment, Los Angeles, CA

Narration Director: Marice Tobias

Narration Engineer: Peter Cutler

Narration Editing: James Ginsburg

Front Cover Photo: Andrew Eccles

Art Direction Booklet: Nancy Bieschke

Inlay Card: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

© 2011 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 124