| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

Store

Biber: Mensa Sonora

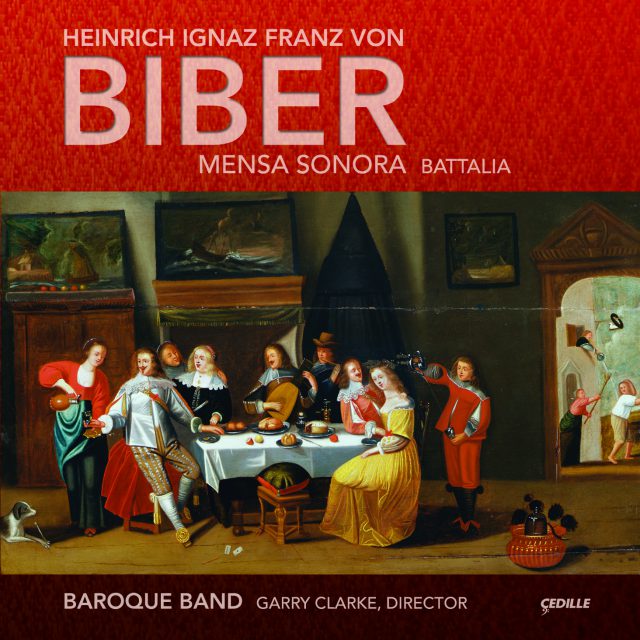

Chicago’s “stylish and exciting period-instrument group” (Chicago Tribune), Baroque Band presents works by Bohemian-Austrian composer Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber. One of the most important composers for the violin in the history of the instrument (the prominent 18th century music historian Charles Burney called Biber the best violin composer of the 17th century), Biber’s Mensa Sonora (meaning ‘Harmonious Table’) was music composed for aristocratic dining, though it is anything but superficial background music. The disc closes with the 10-part Battalia for strings, which uses several unique devices for the time: hitting the strings with the wood of the bow, placing paper under the strings of the basses to imitate a snare drum, snap pizzicatos, and folk songs rendered simultaneously in several different keys to portray drunken soldiers.

Early music specialist Garry Clarke, hailed by the Oxford Times as “one of the finest exponents of baroque music in the [UK],” leads Baroque Band through the feats of virtuosity necessary to execute these exciting pieces. His Baroque pedigree (Academy of Ancient Music, The Sixteen, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, The King’s Consort, The Hanover Band, and the Scholars; plus work with Christopher Hogwood, John Elliot Gardener, and William Christie) led him to found and develop an ensemble with “an abundance of style, a crisp esprit de corps, and a palpable affection for its repertoire.” (Chicago Tribune)

Preview Excerpts

HEINRICH IGNAZ FRANZ VON BIBER (1644–1704)

MENSA SONORA: Pars I in D major

Pars II in F major

Pars III in A minor

Pars IV in B-flat major

Pars V in E major

Pars VI in G minor

Battalia for Violin, Strings, and Basso Continuo in D major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletBiber: Mensa Sonora

Notes by Garry Clarke

The German composer Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) described Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber as “the most important Baroque composer before Bach,” and Biber certainly was one of the most innovative and influential composers of the second half of the seventeenth century.

Born in Wartenburg, north Bohemia, in 1644, the son of a gamekeeper or forester, Biber was to ascend through the ranks of the aristocracy of Salzburg to become Kapellmeister to the archiepiscopal court in 1684 and collect a knighthood from Emperor Leopold in 1690, before his death at age 60 in 1704.

Little is known about Biber’s early musical training except that by the mid 1660’s he was already a master on both violin and viola da gamba. Some scholars believe he was likely trained by the Jesuit musicians at the Gymnasium at Opava in Silesia. The theory behind this speculation comes from Biber’s two middle names, neither of which appear on his birth certificate and which he didn’t start using until about 1676; they are taken from two of the most important founding members of the Jesuit order: Ignatius of Loyola and Franz Xavier. This was an important period in the formation of Biber’s musical style, and much of the innovation of his later compositions, including the use of folk music, programmatic elements, virtuosity, and scordatura (alternative tuning of the violin strings) comes from these early influences.

In 1670, Biber moved to Salzburg, entering the service, as a court music-ian, of Prince-Archbishop Maximillian Gandolph von Khüenburg. Two years later, in 1672, he married Maria Weiss, the daughter of a wealthy Salzburg merchant. In 1679, Biber was appointed deputy Kapellmeister for the Archbishop.

Both works on this disc date from Biber’s time in Salzburg: Battalia from 1673 and Mensa Sonora, published in 1680 and dedicated to the Archbishop of Salzburg (as was much of Biber’s work after 1670).

Mensa Sonora, or “sounding table,” a set of six instrumental suites or “Pars,” subtitled “instrumental table-music with fresh-sounding violin sonorities,” was music for dining — i.e., background music. But it is much more than that. The music may be less technically innovative than much of his violin music and certainly less virtuosic, but Biber employs a range of unexpected melody, harmony, and rhythm, much of which must have been lost for those original diners above the clattering of their knives and forks. Typical of late seventeenth century suites, the Mensa Sonora include many of the dance movements usual in a French suite: allemande, courante, sarabande, gavotte, and gigue. To these Biber adds dances such as gagliarda, balletto, trezza, canario, amener, and ciacona. Pars I, IV, and VI all begin with a sonata and conclude with a sonatina. In Pars I, Biber uses the seven bars of the opening sonata as the conclusion, while in Pars VI the concluding sonatina opens with a motive similar to the opening sonata but then Biber adds an eight-bar presto which leaves us hanging in the air — or mid-mouthful, so to speak.

On most, if not all, currently-available recordings, the Mensa Sonora are performed one to a part. While this is a justifiable solution, I have elected to use a larger ensemble. I have done this for several reasons. First, I believe the relative simplicity of the individual parts indicates that Biber was anticipating more than one player per part. Indeed, Biber himself suggests that Mensa Sonora contains no “eccentric dishes,” a reference to both the sumptuous meal the diners might have been eating and to the relative lack of technical virtuosity or special effects such as scordatura needed to execute the individual parts. If, as I suspect, the intention had been to use a large ensemble, this would have made ensemble playing more straightforward, especially for music that, due to its “background” purpose, may not have received prior rehearsal. Second, we know that many court banquets were extravagant affairs. While it is possible that the music-loving Archbishop had Mensa Sonora played for his private dining, it is at least as likely that it was used for larger gatherings. In this case, larger instrumental forces might have been employed to facilitate the Archbishop hearing at least some of the music over the din of the meal. Third, the Archbishop had a large body of musicians on his payroll — for the visit of the future Emperor Joseph I in 1697, over 100 musicians performed in a costumed entertainment — surely they didn’t all get the night off? And finally, the added depth of sonority produced by a larger-than-one-on-a-part ensemble gives extra weight to the music, reflecting the rich nature of the food being consumed while still allowing crispness and lightness of punctuation and articulation.

In Battalia, or “Battle,” we see Biber at his programmatic best. Here folk songs mix with special effects for a rollicking good time. Biber lets us know what we are in for early on: “Where the strokes are written, one must knock on the violin with the bow. You have to try this” he suggests over a passage in which little daggers are placed over the notes to represent rifle shots. He follows this with “the dissolute horde of musketeers” in which 8 well-known folk songs, all in different keys, are played together representing the drunken revels of the soldiers before battle (prefiguring Charles Ives!). “Der Mars” (The March) brings together fife and drum with the solo violin playing the part of the fife and the violone (bass) acting as drum. Here “[the bassist] must hold a piece of paper against the strings so that it rattles,” suggests Biber. After the call to order and an aria to Bacchus, the god of wine, comes the battle itself, with cannon shots resounding from the bass. “The Battle must not be played with the bow, but rather pluck the string with the right hand. Strongly!” says Biber, anticipating the “Bartok pizzicato” by more than 200 years! After the battle comes the concluding Lament for the Wounded Musketeers.

Biber was known in his lifetime as one of the greatest violin virtuosi of the day. Even 80 years after his death, the eminent 18th century musicologist Charles Burney wrote, “of all the violin players of the last century, Biber seems to have been the best, and his solos are the most difficult and fanciful of any Music I have seen of the same period.” Nonetheless, Biber’s music became largely forgotten through the 19th century. In the last forty years, however, new scholarship and the interest in historical performance practice have revived much of this great and virtuosic music. Biber’s true legacy binds the music of the 17th century to that of the 18th and, alongside such musicians as Corelli and Lully, pushed the limits of violin technique to new horizons, opening the way for Bach, Mozart, and many others to follow.

Album Details

Total Time: 56:50

Producer: Jim Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Art Direction: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

Cover Painting: The Feast (oil on panel), Flemish School (17th Century), Musee Jourdain, Morez, France, The Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded June 9 and 10, 2008 (Mensa Sonora) and November 9, 2009 (Battalia) in Nichols Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago, Evanston, Illinois

Microphones: Schoeps MK21, Neumann KM130

© 2010 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 116