Store

Store

When There Are No Words — Revolutionary Works for Oboe and Piano

Grammy Award-winner Alex Klein, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s principal oboe emeritus, and pianist Phillip Bush perform works by composers from both sides of the Atlantic who were caught up in or deeply moved by 20th-century political turmoil.

The Brazilian-born oboe virtuoso’s passionate project, with its underlying appeal for tolerance, encompasses works by Czech, German, British, American, and Brazilian composers. Much of the music evinces a calm lyricism and melodious beauty that belie the composers’ difficult circumstances. Some were exiled from their native countries, others despaired of impending war. One, Pavel Haas, died in Auschwitz.

Paul Hindemith’s 1938 Sonata for Oboe and Piano, written in Swiss exile, is said to represent happier days in his native Germany. Pavel Haas’s Suite for Oboe and Piano, composed at the outset of Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, shares the complex musical language of his teacher, Leoš Janáček. William Bolcom’s ultimately hopeful Aubade – for the Continuation of Life, written amid early 1980s fears of nuclear war, forges a fragile coexistence between cello and piano. Benjamin Britten’s Temporal Variations, written on the eve of World War II, expresses the composer’s anti-militarism. José Siqueira wrote his tuneful Three Etudes for Oboe with Piano Accompaniment shortly before fleeing Brazil’s military dictatorship. Klement Slavický’s professional musical career had been derailed by the Czech Communist regime by the time he wrote his virtuosic Suite for Oboe and Piano.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview with

Alex Klein on Cedille’s Classical Chicago Podcast

This recording is made possible by generous support from the Sage Foundation

Preview Excerpts

PAUL HINDEMITH (1895–1963)

Sonata for Oboe and Piano

PAVEL HAAS (1899–1944)

Suite for Oboe and Piano

WILLIAM BOLCOM (b. 1938)

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Temporal Variations

JOSÉ SIQUEIRA (1907–1985)

Three Etudes for Oboe with Piano Accompaniment

KLEMENT SLAVICKÝ (1910–1999)

Suite for Oboe and Piano

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletWhen There Are No Words

Notes by Alex Klein & Leon Shernoff

A NOTE ON PROGRAM ORDER FROM ALEX KLEIN

The revolutionary aspect of the works contained on this recording is best categorized into three distinct areas, or chapters within the same book. Paul Hindemith and Pavel Haas came face-to-face with the reality of war mentality in a society controlled by hate. William Bolcom and Benjamin Britten made their music into anti-war statements to caution us against going down that path. And finally, José Siqueira and Klement Slavicky, being forcibly exiled from their homelands, remind us of the cost of political interventions and the backward path leading to migrations, refugees, and ostracism.

For Alex Klein’s further thoughts on the program, please visit: alexoboeklein.com/post/when-there-are-no-words

Historical notes by Leon Shernoff

Notes on the pieces by Alex Klein

HINDEMITH

The life and career of Paul Hindemith shows how deeply integrated both Jews and antisemitic culture were in Germany’s middle class. Hindemith’s wife Gertrud was the granddaughter of the legendary mayor of Dortmund and Frankfurt, Franz Adickes. Adickes’s oldest daughter, Theodore, married Ludwig Rottenberg, a Ukrainian Jew, composer, and principal conductor of the Frankfurt opera, where Hindemith was concertmaster. (Yes, Hindemith married the boss’s daughter.) Theodore’s sister, also named

Gertrud, on the other hand, married Alfred Hugenberg, the right-wing politician and media magnate (a sort of Berlusconi of his time) who was perhaps the most essential person in Hitler’s rise to power.

Hindemith’s major work in the thirties, the opera Mathis der Maler (Mathis the Painter), reflects the conflicts of these interrelationships acutely, and the four-year attempt to get it performed was the high-water mark of the German music establishment’s opposition to the Nazi cultural program. It was commissioned by Wilhelm Fürtwängler, the iconic conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, who threatened to resign unless it was performed. Set during the Peasant War and religious conflicts of the early 1500s, it had a heartfelt message of “Why can’t we all just get along?” while shining an unrelenting light on the human cost of sectarian conflict.

Its protagonist, Mathias Grünewald, was well-chosen, a potentially unifying figure. His art, with what were seen as its expressive Germanic qualities, was well-favored by Nazi art critics such as Wilhelm Pinde, while Grünewald’s support of the peasants in their revolution made him popular with leftists. Hindemith also made its music potentially more unifying and popular by employing folk songs and plainchant. It was by far the most “traditional” and clearly German piece he had ever created. Nazi Minister Hermann Goering absolutely forbade its performance. Meanwhile, Hindemith was pushed out of his teaching position, and by 1938 he and Gertrud had fled to Switzerland, where Mathis der Maler received its premiere, and where he wrote his Sonata for Oboe and Piano.

Hindemith’s Sonata raises questions as to its influences. The first movement is energetic, in the tempo of a military march (♩=120), with oboe and piano starting in conflicting rhythms, as though the march is out of step with itself. The movement never appears to reach a conclusion, instead just fizzling away without definition. Given the kerfuffle with his Mathis der Maler and its rejection by Nazi party officials, it would have been insane, if not deadly (for him and his family) for Hindemith to leave any writings that would reveal whether his oboe sonata implied any derogatory opinions or outright mockery of the German state in 1938. Further hints are left to the imagination, such as in the central development, where the oboe introduces a new downward theme that grows aggressively only to be capped by a triumphant return of the second theme and then recapitulation. This structural idea — made famous by Beethoven (7th and 9th symphonies) and also used in Dmitri Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony, “Leningrad,” ostensibly to describe the German invasion of the Soviet Union — is identified by the dynamic build-up as a theme is incessantly repeated and gains strength. The first movement conveys an image of intense social order, an imposition of norms and discipline lacking the proper comprehension and development of each musical idea. Themes are presented with little or no preparation, usually coming in off-key or as interruptions to the previous material. For us, several decades after the Nazi regime, the musical ideas in this first movement seem to corroborate with historical accounts of what was happening in Germany in 1938.

In contrast, the second movement points to a different scenario. Now we have Wagnerian long phrases, a sense of order through a fugue, oboe and piano complementing each other in rhythm, melody, and chamber music values. Now we have counterpoint that itself is indicative of order, of discipline, and ceding each other the right of way. Now we have closure to themes and sections, and proper transitions, as in the timely preparation for new events. Perhaps the most telling structural feature of this movement is the coda and how it connects to its alter ego in the first movement. In the slow movement of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony we have a fine example of this building structure, where a melody begins modestly and is repeated over time to create a significant sound mass. This same structure is present in the coda of Hindemith’s Sonata: the oboe reintroduces the second theme — the one we commonly associate with peace and calm in Sonata form — and gradually builds on it, repeating in constant crescendo until at the very end it appears to insist on its final chords as though Hindemith is begging for our understanding and acceptance of a specific message, a message made clear through sound. Hindemith leads us to believe that perhaps there was a different path for Germany, one based on its history of art and philosophy, on its culture and values.

HAAS

Pavel Haas was born in 1899, eleven years before Klement Slavický. He thus got to study under Leoš Janáček in Brno, as did Slavický’s father. Both composers grew up in Moravia and included Moravian folk songs in their works. And although they are of nominally different musical lineages — Slavický drew his inspiration from Josef Suk, a pupil of Dvořák — they are similar in their emotional depth and particularly in their refusal to limit much of their music to a single mood, an attitude that Haas made explicit in the title of his Saddened Scherzo, Op. 5. Like Slavický, Haas calls his piece a Suite rather than a Sonata.

Haas enjoyed a fairly privileged life for a while — his family was prosperous and well-connected, and his younger brother Hugo was a famous actor who hooked Haas up with quite a few projects scoring dramatic productions, both movies and live plays. Although nominally avant-garde, his work was an integral part of Czech musical culture until the Nazi takeover. He wrote the Suite for Oboe and Piano in 1938, at the very beginning of the Nazi occupation. Haas divorced his wife to save her and their child from being associated with his Jewishness. Haas himself was deported to Terezin/Theresienstadt in 1941, where he was one of a group of Czech-Jewish composers including Gideon Klein, Viktor Ullmann, and the conductor Karel Ančerl, who were coerced into putting on a series of musical productions the Nazis used for propaganda purposes. After these were filmed in 1944, the musicians were all sent to Auschwitz, where for some reason Dr. Mengele was waiting for them specifically. After the war, Ančerl told the noted Moravian filmmaker Hugo Haas that he (Ančerl) was initially selected to be gassed immediately, but Pavel was very sick and began to cough, and this drew Mengele’s attention, so Haas was gassed instead. Ančerl was the only one of the group to survive the war.

Haas’s Suite was reportedly originally scored for voice and piano, although the text has never surfaced. That this is plausible shows the influence of Janáček on his music. Janáček employed a distinctive style of prosody that avoided the sort of song-melodies characteristic of Western European classical music in favor of a more declamative style that essentially rambled around small fragments. In Western European music, the closest thing would be very late Beethoven. The Janáček vocal style also allows for notes that are simply repeated, quickly and forcefully. This is very unidiomatic in Western European vocal music and is not terribly idiomatic for oboe, either. It is not until the final moments of the piece that we get an extended western-style melody with accompaniment.

In Haas’s Suite we find a treasure of valuable information to aid performers in deciphering his intent and the outcome he would have wanted performances to elicit. Haas first wrote this Suite as a set of songs for voice and piano, setting a nationalistic text exalting the virtues of his homeland. Haas then destroyed the pro-Czech, anti-Nazi\ text attached to the songs and made them into a Suite for oboe and piano instead, changing very little of the original writing, as evidenced by the limited range and dexterity required of the oboist. The musical content, however, has remained, even with the text removed. One can perceive how the first movement establishes a situation, a discomfort, a lack of comprehension of surroundings, with musical themes going by without being properly developed before being replaced by new ones, and near-cadenzas similarly failing to create a sense of continuity. The movement doesn’t have an end, either. It doesn’t reach a conclusion, coda, sense of accomplishment, or closure. In a brilliant stroke of imagination and creativity, Haas permits this first movement to just disappear, raising more questions than answers, much like the thoughts of someone living under oppression, incapable of understanding their surroundings and current events, or establishing a path forward.

The following movement begins with “Nazi bells” represented in the piano part, with the oboe helplessly attempting to launch a challenge. The drama unfolds, the unwinnable battle ensues, and the oboe is eventually buried by the insisting “bells.” It’s as if Haas was aware of how fruitless it was for him, or anyone, to fight the Nazis and the antisemitism he was facing at the onset of the holocaust. But Haas left us a treasure at the end of this movement, a quote from the hymn of Saint Wenceslas, the 10th century ruler who became the patron saint of the Czechs. Haas introduces this chorale after all hope of survival vanishes from the line represented by the oboe/voice, implying that victory over the Nazis lies beyond this life; history, represented by their patron saint, will bring redemption unavailable during his own lifetime. This new theme is not represented submissively as a prayer or a hope to ascend to eternal life. Haas instead presents the Saint Wenceslas chorale as an act of defiance, transcending the challenge that was impossible for him. Haas represents his and his contemporaries’ own predicament in the middle movement by the oboe’s failure to overcome the massive sound structure presented by the piano. I view the introduction of the Wenceslas hymn before this moment’s close, plus the entirety of the third movement after, as a statement that one can kill us but never get rid of our presence. Haas’s music defies the Nazis even as he could not do so in person. The third movement complements this statement, as a vision of eternal glory is presented, post-Nazi, as the “Nazi bells” of the second movement are replaced by a heavenly posture as both performers grow in intensity to a glorious and triumphal end.

BOLCOM

An aubade is a poem written to greet the dawn. This one was engendered by a 1980 (all-night?) conversation among William Bolcom, oboist Heinz Holliger, and conductor/ pianist Dennis Russell Davies about possible nuclear war with the Soviet Union. Almost all of Bolcom’s extant work was created in dialog with the popular music of America’s early 20th century and mid to late 19th century. This piece, however, has no such connection — probably because Holliger is a composer himself, and a fairly hard-core modernist.

Bolcom’s Aubade – for the Continuation of Life came about during a period when the United States and the Soviet Union could have descended into nuclear war. This is key to the loneliness and even helplessness reflected in the score. The Aubade’s climax follows an agitated section that stumbles into a dramatic high note on the oboe followed by similar catastrophic representations in the piano, leading us to consider what would happen if a nuclear war devastated our world. Near its closing, Aubade offers a glimmer of hope, through a simple chorale leading to a resting D major finale, that the world will seek peace rather than war to solve its problems.

BRITTEN

Benjamin Britten’s Temporal Variations are a bit of a puzzle. Although he recorded in his diary that he was pleased with the premiere — and he had rushed to get them finished for the performance — he put them in a drawer afterwards and never pursued publication or further performances. While they are now\ a fairly stalwart part of the oboe repertoire, they were rediscovered and published only after his death. Britten dedicated the Variations to Montagu Slater, an ardent pacifist (as was Britten). Britten had already written incidental music to one of Slater’s plays, about the 1913 Easter Uprising in Ireland. In 1936, Slater wrote a play and a political pamphlet about the coal miners and their strikes.

I once heard Britten’s Temporal Variations performed by the remarkable and ingenious oboist Mark Weiger, who brought to my attention how the cryptic names atop each of its nine movements create a guided anti-war message. The two-note, two-syllable theme is akin to the phonemes of the word “Enough.” The first variation, “Oration,”

represents the period when a political leader encourages war and makes an emotional appeal on its behalf — an appeal that is enthusiastically received by the hordes. The second variation is a military “March,” a slippery slope leading down to the calamity represented by the third variation, “Exercises,” where the unavoidable conflict has no melody other than a small quote from Gustav Holst’s “Mars, the Bringer of War.” The word Britten chose to represent the fourth variation, “Commination,” is a term from Anglican Liturgy representing divine punishment. Fittingly, this divine vengeance is followed by the desolation felt in the “Chorale,” where the piano represents a distant, pathetic call and the oboe quotes a motive originally heard in the first variation. This motive is transformed from pride to shame as the notes are now dispersed and eventually inverted, indicating a change of direction from when this motive was first presented. The “Waltz” and “Polka” come as caricatures of former cultural icons overrun by aggression. In the final movement, “Resolution,” the oboe repeats, insistently, the original “Enough” motive, while the piano is instructed to play fortissimo, con tutta forza (with all strength) chords, notes, and intervals that have little or nothing to do with the musical presentation coming from the oboe. It is as though we are repeatedly screaming “Enough” (to war) but those around us completely ignore our pleas.

SIQUEIRA

Northeastern Brazil has provided us with musical riches far out of proportion to its general status as a regional backwater. In addition to José da Lima Siqueira, it is also the birthplace of legendary jazz musician Hermeto Pascoal and home to Brazil’s oldest professional symphony orchestra, in Recife. Siqueira’s hometown was unusually remote even for the area. Conceição, where his father was the local bandleader, nestles among far inland hills that discourage transportation, agriculture, and indeed civilization. Alex Klein notes that “it might well vie with Timbuktu as one of the farthest, most alienated cities in the world. Its population in 2015 was 18,000, and it was no doubt even smaller when\ Siqueira was born in 1907.”

Brazil has had a politically tumultuous and complex 20th century, even by the demanding standards of Latin America. Siqueira had the good fortune to come of age during the twilight years of one oppressive regime, and so got to spend much of his middle adulthood under the more open government that followed it. He made the most of his chances: along with his activities as a composer and conductor, he created many of Brazil’s musical institutions, founding the Brazilian Symphonic Orchestra and Rio de Janeiro Symphony Orchestra in the forties, and the national musicians’ union, assuming its Presidency in 1960. He also founded Brazil’s National Symphony Orchestra (1961) and the Chamber Orchestra of Brazil (1967).

In 1964, however, that government was overthrown in a coup, and his position became increasingly untenable. Founding the Chamber Orchestra of Brazil may even have been an attempt to create a lower profile position for himself where he wouldn’t be harassed. Paolo Nardi, the dedicatee of Três estudos para Oboé e piano and also Siqueiras’s Concertino for oboe and strings, recalls soloing under Siqueiras’s baton with the Chamber Orchestra in 1970 and 1971; but by the time of Três estudos’ composition in 1969 Siqueira was already an expatriate, living in the Soviet Union, and Nardi himself later left for Italy.

At first hearing, the soft, distant melodies carrying themes, rhythms and harmonies from Siqueira’s native Paraiba, in Northeastern Brazil, appear to indicate nostalgia as, after rising to the pinnacle of influence and respect among his peers, Siqueira saw his lifework prohibited from performance in Brazil. This work appears to represent compositional “etudes” on how to write for oboe, not much different than when Robert Schumann wrote his eponymous pieces for oboe, clarinet, and horn, searching for his voice in them. This exploratory style is revealed in ways that seem to “test” the artistic and technical abilities of the instrument. The middle movement references Paraíba’s typical “Forró” dance, with its fancy-footed moves. The last etude is evocative of the “Seresta,” a traditional and often melancholic Brazilian song, and throughout the entire piece one hears the mixolydian scale, a harmony typical of the Brazilian Northeast.

SLAVICKÝ

Klement Slavický and his wife Vlasta worked for the Czech national radio station until 1951, when they were forced out because he would not join the communist party and he was expelled from Czechoslovakia’s Union of Composers. In an interview that served as his obituary in The Independent (UK), he said that the couple was able to survive only because a Franciscan friend was able to find a “church helper” job for Mrs. Slavický in Kaden, some seventy miles from Prague — a job to which she commuted until 1960.

Slavický is a great source for complexity of emotion. In this and certain matters of texture and spacing, he bears fruitful comparison with another famously political composer, Dmitri Shostakovich.

But Slavický’s music is remarkably free from expressing repression itself.

When Shostakovich writes frisky music, he often warps it, to show the effect of repression on everyday life. The point is the warping, not the friskiness. But when Slavický writes frisky music, it is genuinely joyful and frolicsome. In that “obituary,” he mentions his faith as a firm foundation for his life. His work has a certain sense of security, a sense of living long-term with the emotions his music depicts.

As noted, Slavicky’s music responds only to itself. Although there may have been factors influencing the composer at the time, his 1960 Suite is simply a compilation of sounds ordered to produce auditory and intellectual pleasure. The communist shift in his native Czechoslovakia (that ultimately led to his forced exile) would certainly have been on his mind, and might even be linked to the painfully sad third movement, “Triste,” but it would be difficult to impose such associations on his Suite as a whole. The first movement does invoke a perhaps nostalgic view of the countryside, but that feeling likewise does not speak for the whole Suite, as the bright second and forth movements are alive with positive energy similar to that heard in earlier works and incompatible with the notion of the baring of a soul marred by thoughts of exile.

Leon Shernoff, a graduate of the Eastman School of Music and California Institute of the Arts, is a composer and singer in Chicago. Examples of his work may be heard at www.leonshernoff.com.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Sound Engineer Bill Maylone

Steinway Piano

Technician Richard Beebe

Graphic Design Bark Design

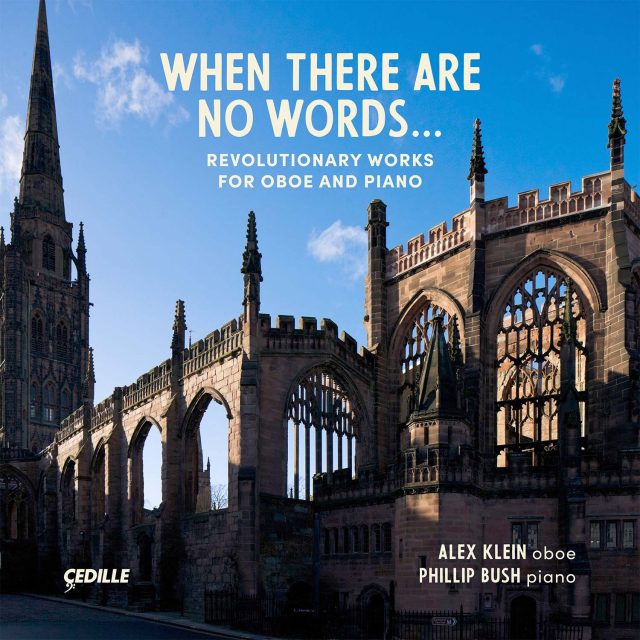

Cover Photo

The ruins of Coventry Cathedral, Ian G Dagnall, Alamy Images

Recorded

July 12–14 and 16–18, 2021, Gannon Hall, DePaul University, Chicago, IL

Publishers

Hindemith © 1939 Schott Musik International

Bolcom © 1982 Hal Leonard

Britten © 1980 Faber Music Ltd

Siqueira © 1969 Deutscher Verlag für Musik

Slavicky © 1963 Editio Supraphon

Oboe: F. Lorée “Etoile”

Alex Klein is grateful to the F. Lorée company for his use of the “Etoile” model oboe on this recording

Cedille Records © 2022

CDR 90000 208