Store

Store

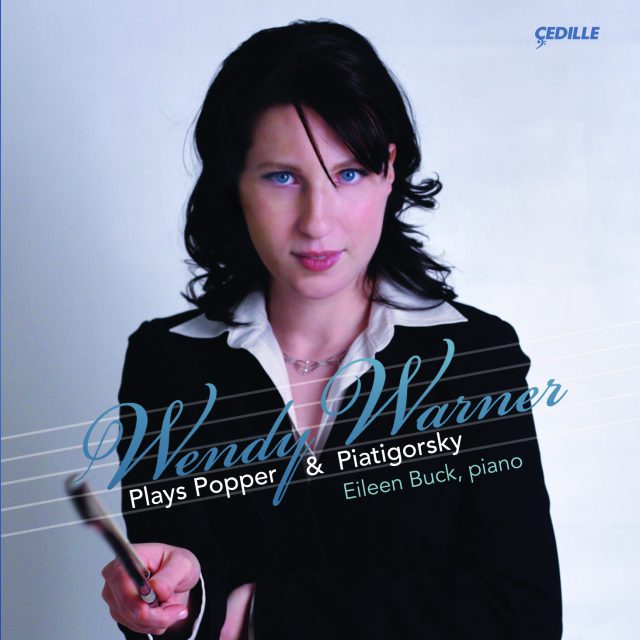

Wendy Warner plays Popper and Piatigorsky

One of today’s finest cellists, Wendy Warner wowed listeners with her enterprising recording of works by Hindemith on Bridge Records, her performance of Barber’s Concerto on Naxos, and her album of duos with violinist Rachel Barton Pine on Cedille.

A “characterful cello soloist” (The Guardian) noted for her “sensitive, polished performances” (Fanfare), Ms. Warner turns her attention to late-Romantic works by composers who were the superstar cellists of their day, focusing her full-frequency tone and artful interpretation on works by David Popper (1843-1913) and Gregor Piatigorsky (1903-1976).

The new CD, with pianist Eileen Buck, features three rarely recorded works by Popper: his Three Pieces, Op. 11; Suite, Op. 69; and the charming Im Walde, Op. 50, a set of colorful pastoral scenes including the mysterious and infectious “Gnome’s Dance.” Piatigorsky’s 14 Variations on a Paganini Theme, a favorite concert crowd-pleaser for Ms. Warner, is every bit as virtuosic for the cello as Rachmaninov’s setting is for the piano.

Preview Excerpts

DAVID POPPER (1843-1913)

Suite for Cello and Piano, Op. 69

Three Pieces, Op. 11

Im Walde, Op. 50

GREGOR PIATIGORSKY (1903–1976)

Variations on a Paganini Theme

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Virtuoso as Creator

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

In the early years of the 19th century, Niccolo Paganini wowed audiences throughout Europe with his superb violin technique, augmented by an innate knack for showmanship. Paganini’s sold-out recitals featured his own compositions and arrangements, the latter often based on popular opera arias. Each program was calculated to display his special skills on the violin. And thus were born twin traditions: those of the virtuoso solo recital and of the composer-virtuoso.

Inspired by Paganini’s success, Franz Liszt adapted the idiom to his own instrument, the piano, and achieved even greater triumphs. Many musicians and music-lovers who heard Liszt survived into the 20th century and passed on to their students, friends, and descendants first-hand accounts of his brilliant bravura and ability to transform the keyboard into a virtual orchestra. So even though recording hadn’t been developed during Liszt’s lifetime (1811–1886), his legend survived into quasi-modern times from accounts that identified him as THE great piano virtuoso of all time.

Liszt had major impact beyond his pianistic pyrotechnics. He composed for orchestra as well as for piano, pioneering the genre of the symphonic poem, moving away from traditional compositional procedures such as sonata form, and constantly experimenting with harmony (some of his late piano scores push the bounds of tonality). Wagner was much influenced by Liszt, or it might better be said that they influenced each other. As a composer-virtuoso Liszt left a legacy to succeeding generations, inspiring talented players to develop the potential of their instruments to create both new music and successful careers. One of these was David Popper.

Popper was a Liszt protégé as well as an influencee; Liszt appointed him to the faculty of the National Hungarian Royal Academy of Music in 1886, and he was briefly married to one of the older master’s most famous students: pianist-composer Sophie Menter. Popper came to the cello by a sort of accident. The son of a Prague cantor, he initially studied the violin, but when he went to the Prague Conservatory at the age of 12, the school had too many aspiring violinists and not enough cellists; so he was assigned to the cello, and within a few years was regularly substituting for the official cello professor. He went on to lead the cello sections of several orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic, but his solo career eventually took precedence. Popper wrote a teaching method and a great many compositions for cello: four concertos, an instrumental Requiem featuring three soloists, and several recital pieces with piano. Later generations have tended to sneer at these last works as “salon pieces,” yet they are most enjoyable to hear. They show off the instrument’s sonority to great advantage, give interest (and challenges) to the pianist, and are full of the rich, close, tonal-yet-chromatic harmonies favored by Liszt, Wagner, and their followers. Furthermore, Popper was an accomplished melodist, and his themes allow the cello to sing with a most beautiful voice.

This CD contains three short Popper recital pieces, plus two longer suites, one descriptive in the tradition of 19th-century program music, the other more abstract, leaning toward the tradition of the cello-piano sonata. Popper’s Op. 69 Suite for Cello and Piano opens with a movement titled “Allegro giojoso,” which should mean Lively and Joking. It’s really more rhapsodic than it is joking. In it we hear the composer’s fondness for chromatic harmonies, wide-ranging melodies, and full chords. The virtuoso element is strong for both players; the full range of each instrument is skillfully exploited. The structure is a basic A-B-A progression. For the second movement, Popper takes us back to the 18th century with a “Tempo di Minuetto.” Where the first movement was cast in a compound meter, 9/8, this one is in the standard 3/4 time that Haydn would have used for the minuet movement of a symphony. A simple opening melody is quickly enhanced with chromatic tones and brief shifts away from the basic D Major tonality. There’s a soft Trio section with an elaborate cello theme, mostly in 16th notes; the return of the Minuet theme is marked Grazioso (Gracefully), a word that sums up the entire movement to perfection.

It’s a strong contrast to the evocative “Ballade” that follows. An Adagio in the key of F-Sharp Minor, this movement negates the genial mood of what has come before with dramatic chords and tremolos in the piano part, while the cello presents a wandering succession of motives characterized by falling half-tone and seventh or diminished-octave intervals that produce a sense of tonal and emotional insecurity. Hesitant dotted rhythmic figures are frequent. The movement dies away to a soft, ominous ending. The “Finale,” marked Allegro con brio, brings back a cheerful mood and sets right out with a virtuosic, highly chromatic theme for the cello in 16th notes. Pizzicato (plucked) passages punctuate the melodies played with the bow. The piano echoes and augments the cello’s line with big chords and rapid passages in 16th notes that contribute to the movement’s sense of forward-rushing intensity. A Molto tranquillo (very peaceful) passage lightens the mood and the texture before the opening thematic material returns. The cello part, with staccato chords in the piano, becomes almost like an accompanied cadenza passage in a cello concerto. The piano also has some brief solos, but for the next return of the main theme the players perform together. A low, fortissimo cello note over a complicated piano run diminishes in volume to pianissimo as we come to the final section, marked Presto. Although everything’s been quite fast so far in this movement, the pace picks up still further as we hear the main theme once more, played mostly staccato by the cello with frenetic accompaniment from the piano. The fortissimo final measures feature a cello harmonic and emphatic A Major piano chords.

Popper may have played the three pieces of his Op. 11 as a single set on his recitals, or he may sometimes have used them individually as encores. The German word “Widmung” means Dedication; it’s the title of one of Schumann’s most famous songs, and Popper’s piece is a song without words subtitled Adagio for Cello and Piano. The key is F Major, the pace slow and heartfelt; from an intensely lyrical opening the sounds become more impassioned, the emotions ever more agitated, until a pianissimo ending evokes a peace tinged with sadness. “Humoreske” is what it implies. The cello dances with staccato, accented figures augmented by octave passages for the piano. The cello line is virtually nonstop, while the piano’s part is occasionally slowed down and intensified with sustained chords. The mazurka is a triple-meter Polish dance popularized by Chopin’s use of its rhythm in several sets of piano pieces. This “Mazurka” features staccato dotted and triplet figures for both players; the final section, moving from pianissimo to fortissimo, is repeated. Lebhaft, the tempo marking, means Lively; the piano’s opening passage is further marked “Wild,” unmistakably conveying the basic pace.

Im Walde, Op. 50, is Popper’s six-movement suite evoking forest scenes and moods. Originally scored for cello and orchestra, in its reduced version it requires the pianist to call forth an almost symphonic sonority via chordal passages, tremolo chords, vivid accents, and strong octaves. Both cello and piano are given ecstatic, long-breathed melodies and mostly cheerful-sounding harmonies (this is for the most part a sunlit forest). “Eintritt” (Entrance), in E-Flat Major, gives us another taste of the chromatic-tinged harmonies Popper favors. It’s a rhapsodic introduction, exulting in the freedom and solitude this particular forest visitor is enjoying. The mood changes for “Gnomentanz” (Gnomes’ Dance), which begins in G Minor with sinister lower-register figurations in both parts. The dynamic is piano; perhaps we can’t quite see the gnomes dancing, but we know these sometimes-threatening creatures are close at hand. It’s a fast dance that builds in intensity until a more relaxed G Major midsection, which is followed by an elaborated recapitulation of the original dance theme. A fortissimo chord (pizzicato on the cello) makes an abrupt conclusion. The mood changes radically once again for “Andacht” (Devotion), an emotional statement of love and longing. We can imagine the forest visitor suddenly overcome by nostalgia, remembering a life experience far removed from his current forest surroundings. The cello themes, intensely lyrical, are partnered by rapid, agitated runs and chords for the piano. Mostly in a soft dynamic, the texture is dramatized with sudden crescendos and diminuendos. The key is a return to E-Flat Major.

“Reigen” is a Round Dance far removed from the ghostly echoes of the gnomes in movement two. This dance, in G Major and 3/4 time, is a cheerful celebration of the beauties of nature and the joy of being alive on a sunny day. The cello roams up and down its range and plays some fast-paced chromatic runs as the piano supports with strong chords. Both instruments tumble to a headlong conclusion, punctuated by cello harmonics — high-pitched notes created by fingers lightly pressing the strings, instead of pushing them down all the way — giving an ethereal echo effect. The very short fifth movement, called “Herbstblume” (Autumn Flower), is a lyrical, gem-like character-piece in B-Flat Major. This is the forest visitor’s final glimpse of the beauties of the forest, as we come to the Allegro Vivace “Heimkehr” (Homeward) movement in 6/8 time. Nearly constant motion in both parts seems to imply that our forest wanderer is being recalled to ordinary life after his semi-magical woodland sojourn. The cello has some almost cadenza-like runs, the piano has thick, closely-bunched chords elaborated often by trills. There are sudden accents and numerous forte-piano dynamic shifts. Toward the end, a fugal theme is introduced by the two hands of the piano and taken up by the cellist’s single line; the sound begins to die out and the pace is retarded until a final strong chord. We’re home.

Popper was one of the pre-eminent European cellists of the 19th century; Gregor Piatigorsky won worldwide admiration in the first half of the 20th. Born in Ukraine, a graduate of the Moscow Conservatory, Piatigorsky became principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwangler at the age of 21, having emigrated from the fledgling Soviet Union. Like Popper, though, he soon left the symphony-orchestra milieu to embark on a solo career. Later he would become a distinguished teacher on the faculty of UCLA. Chamber music was an important part of his life: at the Boston Symphony’s Tanglewood Festival and in partnership with violinist Jascha Heifetz. In addition to playing the Romantic-era works in which he was most at home, Piatigorsky gave several important world premieres, including concertos by Hindemith, Walton, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco. And like other virtuosi before him, he tried his hand at composition. Our CD concludes with a set of variations he wrote originally for cello and orchestra, and later arranged for cello and piano.

Its theme is one of the most famous in all of Western music, and it takes us right back to the start of the virtuoso tradition, since it’s the subject of Paganini’s Solo Violin Caprice No. 24. Composers from Brahms to Andrew Lloyd Webber have exploited this theme with dazzling results. Piatigorsky lays out the theme in a brief Allegro introduction, giving it to the cello while the piano supports with chords. It’s a brief two-part theme in A Minor, both halves repeated; the melodic and harmonic outlines of the theme remain constant, so there’s always a clear echo of the original throughout the variations. Piatigorsky structured his variations as whimsical tributes to some of his performing colleagues. The Canadian cellist Denis Brott, a former Piatigorsky student, has identified the artists associated with each variation:

Variation 1, Moderato, Espressivo, A Minor, 3/4 time: Pablo Casals. Smooth legato cello playing with octaves in the lower register of the piano

Variation 2, Energico, A Minor, 4/4 time: Paul Hindemith in his role as viola virtuoso. Forte dynamics, strong accents, rapid passage-work in both parts.

Variation 3, Allegro, Leggiero, A Minor, 2/4 time: Raya Garbousova, a Georgian-born cellist who performed and taught extensively in the U.S. Light and fleeting figurations for the cello over syncopated eighth-note piano chords.

Variation 4, Vivo, Leggiero, A Minor, 2/4 time: Erica Morini, a child-prodigy Viennese-born violinist whose career was furthered by Furtwangler; she ceased performing in the 1950s and died almost forgotten. This variation features double-stops and octaves for the cellist echoed by brief piano comments.

Variation 5, Siciliana, A Major, 3/8 time: Felix Salmond, an English cellist who gave the world premiere of Elgar’s concerto in 1919. The gently rocking “Sicilian” rhythm frames gentle lyricism in both parts, before an abrupt harmonic shift in the piano takes us without pause to:

Variation 6, Adagio, D Minor, 6/8 time: Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti. Double stops on the cello and rumbling piano chords produce an almost brooding atmosphere.

Variation 7, Allegro Moderato, A Minor, 4/8 time: Yehudi Menuhin. The piano is prominent with fast passage-work, the cello leaps up and down almost its entire range.

Variation 8, Presto, A Minor, 4/4 time: Nathan Milstein. Very rapid cello runs emphasize virtuosity; there’s a soft dynamic until the final accented chord.

Variation 9, Allegretto, A Minor, 4/4 time: violinist Fritz Kreisler, perhaps the most famous composer-virtuoso of the early 20th century. Mild and tuneful, this relaxed variation recalls Kreisler’s own encore pieces.

Variation 10, Tempo di Tema (Allegro), A Minor, 2/4 time: This is a Piatigorsky self-portrait with triplet figurations for the cello over a staccato piano part. The motion is nonstop.

Variation 11, Quasi Scherzando, A Minor, 6/8 time: the Spanish cellist-composer Gaspar Cassado. Triplets and grace notes in the cello part, plus numerous chords, with the piano echoing and letting the cello lead

Variation 12, Con Passione, A Minor, 12/8 time: violinist Mischa Elman, a beloved virtuoso of the first half of the 20th century. The piano comes to the fore with fast runs as the cello plays a more sustained line with offbeat accents.

Variation 13, Allegro, A Minor/Major, 4/4 time: Ennio Bolognini, an Argentinean-born artist who made most of his career in the U.S.; he played flamenco guitar as well as the cello. Rapid cello figurations are succeeded by chromatic double-stops in the A Major portion, while the piano has numerous rolled chords (a la guitar?). There are several sudden loud-soft dynamic contrasts.

Variation 14, Allegro Ma Non Troppo, A Minor, 4/4 time: Jascha Heifetz. Crisp staccato figures for both players, trills, and chromatic scale passages for the cello. The pianist does not use the sustaining pedal. A brief, to-the-point variation, with a transitional passage leading us to:

Tempo di Marcia, A Minor/Major, 4/4 time: Vladimir Horowitz. Dramatic dynamics give us one long crescendo from pianissimo to fortissimo. Double stops and octaves for the cello mimic piano figurations rendered in Horowitz’s dramatic style. The conclusion features brilliant cello runs and powerful keyboard chords.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical music station

Album Details

Total Time: 79:30

Producer: Judith Sherman

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Session Director: James Ginsburg

Recorded: August 27-31, 2007 (Popper Op. 11 and Op. 69) and June 26-27, 2008 (Popper Op. 50 and Piatigorsky) in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago

Cellos: Joseph Gagliano, 1772 (Popper Op. 11 and Op. 69); Carl Becker, 1963 (Popper Op. 50 and Piatigorsky)

Steinway Piano, Piano Technician: Charles Terr

Art Direction: Adam Fleishman – www.adamfleishman.com

Front Cover Photo by Oomphotography – www.oomphotography.com

© 2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 111