Store

Store

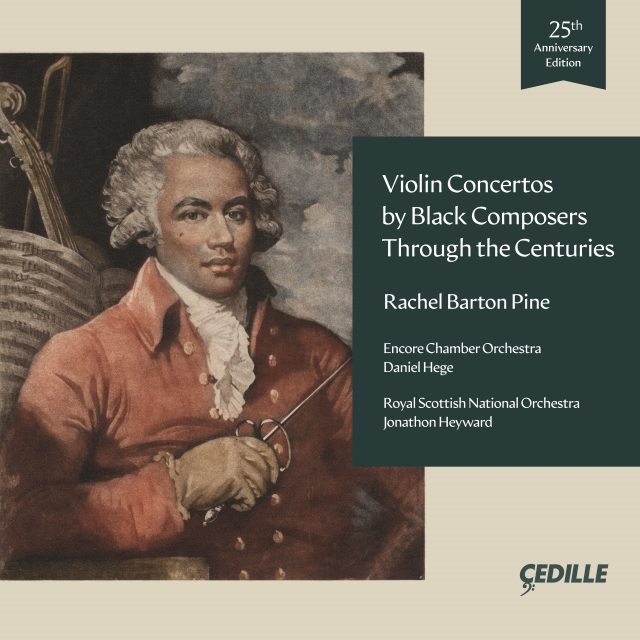

Violin Concertos by Black Composers Through the Centuries

Encore Chamber Orchestra, Daniel Hege, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Jonathon Heyward

American violinist Rachel Barton Pine marks the 25th anniversary of her 1997 recording of violin concertos by Black composers of the 18th and 19th centuries with Violin Concertos by Black Composers Through the Centuries. This special-edition reissue updates and expands the original program into the 20th century with Pine’s recent recording of Florence Price’s Violin Concerto No. 2, composed in 1952. The 1997 release established the violinist’s reputation as a passionate advocate for composers of African descent.

Pine recorded Price’s Second Violin Concerto with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, conducted by American conductor Jonathon Heyward, newly named Music Director Designate of the Baltimore Symphony (at age 32). The violinist reprises her previous recordings of masterworks by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1775), José White Lafitte (1864), and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1899), all with Chicago’s Encore Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Daniel Hege. The New York Times declared: “Rachel Barton [Pine] handles the concertos’ varied demands with unaffected aplomb, performing this music lovingly.” The Chicago-based artist has been hailed as “an exciting, boundary-defying performer” by the Washington Post. The New York Times described her as “striking and charismatic … she demonstrated a bravura technique and soulful musicianship.” Violin Concertos by Black Composers Throughout the Centuries is Pine’s 22nd Cedille Records album. Her discography also includes critically acclaimed recordings on the Avie and Warner Classics labels.

For a complete listing of orchestra members who appeared on this recording, click here: Orchestra Listing for Violin Concertos by Black Composers Through the Centuries

Preview Excerpts

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799)

Violin Concerto in A major, Op. 5, No. 2

José White Lafitte (1836-1918)

Violin Concerto in F-sharp minor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Artists

1: Rachel Barton Pine; Encore Chamber Orchestra; Daniel Hege (conductor)

8: Rachel Barton Pine; Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Jonathon Heyward (conductor)

Program Notes

Download Album BookletNotes by Rachel Barton Pine and Mark Clague

Personal Note by Rachel Barton Pine, 2022: This album is dedicated with love to the memory of Michael Morgan, Robert Fisher, and Terrance Gray, all of whom we lost far too soon. Your work as performers, educators, and advocates for diversity, equity, and inclusion in classical music will always remain a shining example and inspiration.

Sometimes an album can change your life. I’ve been fortunate to have had several.

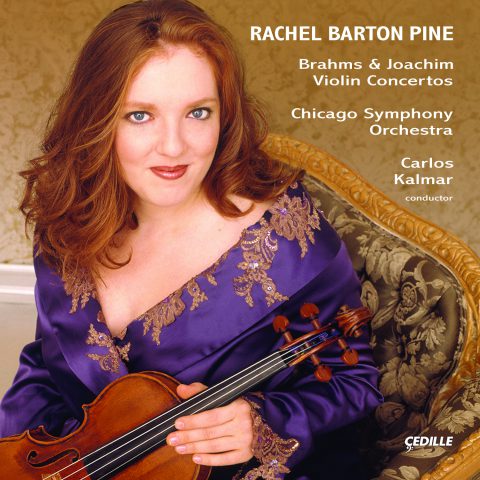

My beloved baroque chamber group, Trio Settecento, was formed following my 1997 recording of Handel Sonatas. My 2002 recording of the Brahms and Joachim Violin Concertos led to the lifetime loan of “my” extraordinary “ex-Soldat” Guarneri “del Gesu” violin.

Violin Concertos by Black Composers of the 18th and 19th Centuries opened my eyes to the lack of awareness of and access to the repertoire and history of Black composers. Its release, 25 years ago, generated an outpouring of requests from students, teachers, and parents for more information about these composers and where to obtain their music. To meet this need, my Rachel Barton Pine (RBP) Foundation created its Music by Black Composers (MBC) initiative in 2001. MBC has been a primary focus of my research and advocacy efforts for over 20 years.

The genesis of this album began several years earlier when I was 17 years old and concertmaster of the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony’s training ensemble. Our principal conductor, Michael Morgan, programmed a groundbreaking concert entirely of works by Black composers. I was invited to give the modern-day premiere of a recently rediscovered concerto by an 18th-century French composer, the Concerto No. 1 in D major by J.J.O., Chevalier de Meude-Monpas.

It was a delightful piece. When Cedille Records offered me the opportunity to record my first concerto album, I immediately thought of this virtually unknown work. Curious about what other violin concertos had been written by Black composers, I visited the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago (CBMR). There I discovered a treasure-trove of fantastic music spanning 300 years, including

works for violin and orchestra by Joseph Bologne (the Chevalier de Saint-Georges),

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Roque Cordero, Anthony Davis, Julia Perry, George Walker, Gregory Walker, and José White.

With so many wonderful options, I decided to focus on the most historical works. Joseph Bologne, whose portrait graces the cover of this album, was the greatest violinist (and greatest swordsman) in France during his lifetime. Although he is still often referred to as “The Black Mozart,” he was the elder composer and inspired Mozart, so it should really be the other way around, with Mozart as “The White Bologne.” Of his numerous concertos, my favorite is Op. 5 No. 2 in A major, and I’ve been fortunate to perform it many times with orchestras throughout the world. I believe that some of the more extreme demands he places on the bow arm must have been inspired by his prowess as a fencer!

I love virtuosic repertoire from the Romantic period and was extremely excited to discover José Silvestre de los Dolores White y Lafitte. He was George Enescu’s teacher, making him Yehudi Menuhin’s grand-teacher! His artistry and virtuosity were consistently compared favorably to his classmates Sarasate, Wieniawski, and Vieuxtemps. After many years of trying to get this wonderful concerto programmed, I finally had the opportunity to perform it with orchestra this season. I sincerely hope that presenters and my fellow violinists will embrace it and share it with audiences everywhere.

I had hoped to include Coleridge-Taylor’s Violin Concerto on the original recording. … some of the more extreme demands he places on the bow arm must have been inspired by his prowess as a fencer! It is a beautiful piece and was written for my violin hero, Maud Powell, but it was too long to fit. Fortunately, he wrote a gorgeous Romance in G for Violin and Orchestra that rivals those of Dvořák and Beethoven. I’ve performed it a few times and hope that it will soon become more regularly programmed.

In a strange twist of fate, recent research has concluded that the composer who started it all — Meude-Monpas — was probably not of African descent. Scholars now believe that the appellation of “Le Noir” appended to his title did not refer to his ethnicity, but to the color of his horse. Ironically, the “Black” composer that inspired my journey with this body of repertoire wasn’t actually Black!

In light of this revelation, we decided to replace the Meude-Monpas Violin Concerto with another work, by an undisputedly Black composer, for this 25th Anniversary Edition release. When I first visited CBMR back in 1996, I was shown a single manuscript page from a violin concerto by Florence Price and told that this work, and indeed much of her music, had been lost forever. You can imagine my joy when her violin concertos were unexpectedly discovered in an old trunk just a few years ago. Her Violin Concerto No. 2 was the perfect piece to add to the album: a 20th-century work by a woman composer.

Interpreting the Florence Price Violin Concerto No. 2 was a challenge. The vast array of resources that are typically available for works by historic white, male European composers do not exist. There are no dissertations discussing the history of the compositional process or published analyses putting the work into the context of the composer’s broader output. Performance traditions passed from teacher to student going back to the time of the concerto’s premiere are simply missing. Fortunately, I had access to her manuscripts. Jonathon Heyward and I had to make decisions based on our instincts and best guesses, and I’m very grateful to him for his care and commitment to doing justice to Price’s masterpiece. I can’t wait to share this concerto with live audiences this season and beyond.

It’s been wonderful to see the music of Bologne, Coleridge-Taylor, Price, and others growing ever more popular and finding their long overdue place in the repertoire. I urge everyone to seek out and play works by as many Black composers as possible. Please take advantage of MBC’s website containing numerous free resources, including directories of over 150 historic composers and more than 300 living composers. There are still so many undeservedly neglected works to discover and share!

I’m occasionally asked if it’s appropriate for me, as a white artist, to perform repertoire by Black composers. Interestingly, no one ever asks the same question when I play Tchaikovsky or Sibelius even though I’m neither Russian nor Finnish. While other genres may struggle with cultural appreciation versus appropriation, I believe that classical composers want their music to be as widely heard as possible. As classical performers, it’s our joy and responsibility to study and share as much great music as we can, so we can better understand each other’s humanity. I’ve witnessed the music of Beethoven bring tears to the eyes of a Black audience in Ghana, and the music of Coleridge-Taylor bring tears to the eyes of primarily-white symphony patrons in the U.S. Sharing all of this music is cultural celebration!

Please join me in celebrating the 25-year anniversary of this groundbreaking recording and these extraordinary composers whose remarkable works inspire everyone who loves classical music and the violin.

The Social Power of Creativity: The Search for Equality through Cultural Virtuosity

Notes by Mark Clague

Scholars have identified two possible and markedly contrasting derivations for the term “concerto.” Each has resonance for the musical and social parameters that surrounded the creation of the works by Black composers on this recording. One school of thought emphasizes the contentious juxtaposition of soloist and ensemble by tracing the term “concerto” to the Latin verb “concertare,” meaning “to fight” or “to contend.” Indeed, the concertos recorded here were and remain social weapons —tools created by their authors to express their humanity against a countercurrent of racist limitations.

A second line of reasoning traces the term through a variant spelling, “conserto,” to the root verb “conserere,” which in Latin means “to join together.” This derivation highlights the partnership between orchestra and soloist and by extension composer and society. Each of these composers — three active in Europe and one in the United States — used their talents and unusual access to musical institutions and training to leverage the traditions and tropes of the Western European concert tradition to claim space in a prevailing white musical culture.

All four composers heard on this album participated in the musical dialogues of their eras, with the requisite skill, awareness, and experience to create compositions that engage and expand upon musical tradition. Their work is in conversation with the solo violin repertoire of Mozart, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Wieniawski, and Sibelius. Yet these works are never simple imitations; they confront the classical tradition and extend it, revealing a unique creative personality.

None of these concertos quote African-derived melodies or rhythmic signatures in an obvious way. On one hand, direct knowledge of African musical practice was limited in the 18th- and 19th-century European orbit. On the other, composers such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and, later, Florence Price might reference African or African-American music in certain works, but they were not inspired exclusively by or in any way limited to this technique.

Each concerto nevertheless gives voice to a multifaceted personal experience, offering a statement of individual humanity, and by extension, a claim to universal rights for a people too often unjustly reduced to commodity status by the historical legacy of the slave trade. To be a composer is to be a creator, an artist, and a slave to no one.

The inspiration for this recording began in 1992 when the Civic Orchestra of Chicago and its conductor, Michael Morgan, asked violinist Rachel Barton Pine to perform Concerto No. 4 in D major by Le Chevalier de Meude-Monpas (ca.1740–1810) as part of a concert of orchestral music by Black composers. Programmed alongside premieres of 20th-century American works by Ed Bland, Gary Powell Nash, and Henry Heard, as well as Hale Smith’s Innerflexions and Alvin Singleton’s Sinfonia Diaspor

Album Details

PRODUCER

James Ginsburg

ENGINEERS

Lawrence Rock

Hedd Morfett-Jones

(Price session engineer)

Bill Maylone

(Price mixing engineer)

EDITING

David Dieckmann

Bill Maylone (Price)

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Bark Design

COVER PHOTOGRAPHY

Lisa-Marie Mazzucco

RECORDING SESSION PHOTOGRAPHY

Sally Jubb Photography

VIOLINS

Amati, Antonius & Hieronymous, Cremona, 1617, the ‘ex-Lobkowicz’

Guarneri “del Gesù,” Cremona, 1742, the ‘ex-Bazzini, ex-Soldat’ (Price)

STRINGS

Dominant Stark Vision Titanium Solo by Thomastik-Infeld (Price)

BOWS

Victor Fetique

Dominique Pecatte (Price)

RECORDED

June 3–5, 1997, Chapel of St. John the Beloved, Arlington Heights, Illinois

January 7, 2022, Scotland’s Studio, Glasgow (Price)

PUBLISHERS

Price © 2018 G Schirmer Inc.

CDR 90000 214