Store

Store

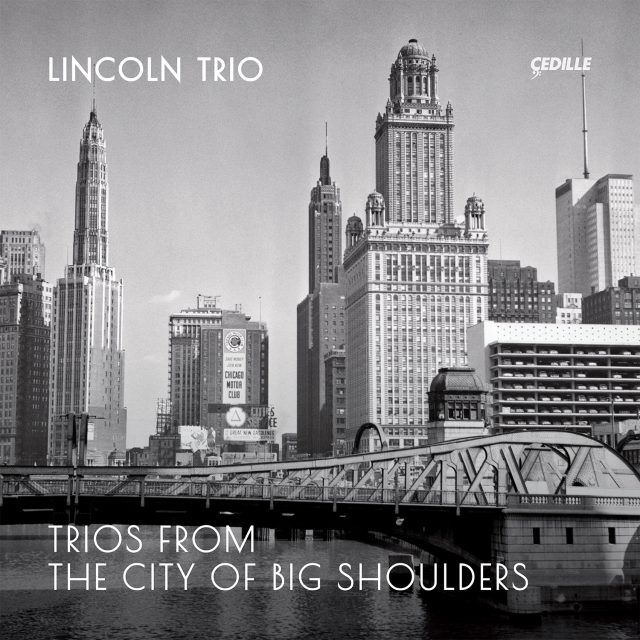

Trios From the City of Big Shoulders

Leo Sowerby, Ernst Bacon, Desirée Ruhstrat, David Cunliffe, Marta Aznavoorian

The twice-Grammy-nominated Lincoln Trio — violinist Desirée Ruhstrat, cellist David Cunliffe, and pianist Marta Aznavoorian — offers engaging, rarely heard piano trios by 20th-century Chicago composers Leo Sowerby, winner of the Rome Prize and Pulitzer Prize for music, and Ernst Bacon, recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships and a Pulitzer Fellowship.

Bacon’s Trio No. 2 for Violin, Cello and Piano (1987) receives its world-premiere recording. Hailed by The New York Times as “a Composer Known for Echoing America,” Bacon infuses the six-movement trio with American influences including marches, folksong-like melodies, and jazz rhythms, validating Virgil Thomson’s assessment of Bacon’s music as “full of melody and variety; honest and skillful and beautiful.”

Sowerby’s Trio for violin, violincello and pianoforte (1953) is “a work of tremendous integrity” that exhibits an “imposing structure, contrapuntal gymnastics, and a concern for instruments sounding as good as they can” (Classical Net). Sometimes virtuosic, sometimes reflective, the work is distinguished by an ever-evolving rhythmic and harmonic interplay between instruments.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Marta Aznavoorian on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

ERNST BACON (1898–1990)

Trio No. 2 for Violin, Cello and Piano

LEO SOWERBY (1895–1968)

Trio for violin, violoncello and pianoforte (H 312)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletNotes by Elinor Olin

Ernst Bacon (1898–1990)

Trio No. 2 for Violin, Cello and Piano (1987)

In many ways, Ernst Bacon’s career was a mirror image to that of his contemporary, Leo Sowerby. Bacon was born and grew up in Chicago, but the majority of his musical activity took place on the East and West coasts. Like Sowerby, Ernst Bacon was a pianist, composer, educator, and Pulitzer award winner (in 1932 for his Symphony No. 2 in D minor). Both men were also influenced by Glenn Dillard Gunn (1874–1963), pianist, conductor, noted music critic for several Chicago daily papers, and founder of the American Symphony in Chicago, who was a strong advocate for American composers in the early 20th century. In contrast to his Chicago confrere, though, Bacon is primarily remembered as a composer of secular vocal genres: choral music, operas, and hundreds of art songs, especially settings of poetry by Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. After studying mathematics at Northwestern University and history at the University of Chicago, Bacon travelled to Vienna for private study in piano, music theory, and composition. Returning to the U.S., he was hired as an opera coach at the Eastman School of Music. Bacon then moved to San Francisco, where he was appointed as Director of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Music Project (1934–1937) and founded the Carmel Bach Festival in 1935. In the late 1930s, he moved East and served as an music administrator, first at Converse College (South Carolina) and later at Syracuse University. He was awarded three Guggenheim Fellowships and authored several books, including Words on Music (1960) and Notes on the Piano (1963). Many of his compositions were published by major houses, including Universal Edition, G. Schirmer, and Carl Fischer. Bacon retired to Orinda, California (near Berkeley), continuing to compose into his late 80s (including the present piano trio).

Much of Bacon’s chamber music was written for two players: a solo string or solo wind instrument plus piano. Many chamber compositions from the early part of his career were influenced by literature or folk songs, bearing descriptive sectional titles such as “Frog in the Well” or “Monadnock at Dusk.” The two piano trios in his oeuvre are late compositions, written in 1980 and 1987, respectively, and are not labelled with programmatic descriptions. Trio No. 2 is a six-movement work with mostly Italian traditional tempo markings, but the musical content is infused with American influences including marches, folksong-like melodies, and jazz rhythms. Overall, Virgil Thomson’s 1946 assessment of Bacon’s music remains applicable here: “full of melody and variety; honest and skillful and beautiful.”

In her program note for a 1998 performance in New York’s Merkin Hall, celebrating the composer’s centennial, Bacon’s widow, Ellen, wrote:

The Trio No. 2 was composed when Bacon was in his late 80s. Its large proportions combine the vigor of more youthful works with the increasing profundity of age. Bacon believed that all music, whether vocal or instrumental, should retain an essential connection with humanity — not only with the human voice in its rich scope of expressiveness, but also with the body and its movements of walking, running, waltzing, romping, and so forth. Like most of his chamber works, the Trio No. 2 is full of melodic ideas derived from his own art songs, as well as from folk songs and dances.

The two-part first movement begins in a contemplative mood with layered, conversational melodies in the violin and cello, the piano commenting in the background. Dramatic intensity builds with string tremolos and syncopated, open chords doubled in the piano and violin. A somber, reflective melody (inspired by Bacon’s own setting of Dickinson’s “The Sun went down — no Man looked on —”) is sprinkled with expressive dissonances and shared by all three instruments, as the compass of the music becomes more wide ranging and expansive. Part Two, marked “In Deliberate March Time,” continues with the same tonal center. Its opening melody is a hiking song, reminiscent of a Civil War-era tune. As it develops, phrases lengthen while fragmented melodic materials appear in sequential repetitions.

The second movement, “In an easy walk,” begins with rambling dotted rhythms in the piano against arpeggiated multiple stops in the strings. Delicate pizzicato statements in the violin and cello comment on wandering triplet figurations in the piano that develop into the spontaneity of a cadenza. The easygoing opening material returns, now transformed into a more insistent discourse among the three instruments, ending in a recombination of elements from the movement as a whole.

The third movement is a nocturne. Marked “Gravely expressive,” much of it presents the cello in quiet meditation (marked “as if gently singing”) against expressive harmonies in the piano. The fourth movement, labelled simply “Allegro,” is a jazz-influenced romp — practically a hoe-down — with playful, syncopated passages exchanged among all three instruments. Often virtuosic, occasionally sentimental, it is a toe-tapping musical excursion.

The brief fifth movement, “Commodo,” features flowing melodies in the piano with a gentle breeze of an accompaniment in the strings. The initial melody (based on Bacon’s song setting of A.E. Housman’s “Farewell to a name and a number”) is taken up successively by the violin and cello as the piano’s commentary, marked “a mere murmer,” sorrowfully concludes the exchange. The trio’s final movement, “Vivace, ma non presto,” features insistent triplet passages that morph into a syncopated folksong melody (specifically “Green Mountain”) in a strong, rhythmic discussion between violin and cello. A new section offers variations on the folkdance theme in the cello and violin, now in a quieter mood against a flowing piano accompaniment. The movement builds in intensity with an accelerating, repeated note figuration leading to the emphatic final cadence.

In his book, Words on Music, Bacon expressed his persistent confidence and commitment to the “authentic musical speech of America.” Noting that “art can passively reflect its times, or it can actively mold its times,” Bacon advocated for music that “continues to sing of ecstasy, reverence, grandeur and lovingness.” At the end of his life, in an article signed “Ernst Bacon, composer-in-eclipse, for the present,” he proclaimed a manifesto of sorts: “Excellence means making the best music with the resources at hand. It implies vitality, enterprise, much independence, and exalted leadership.… It means that native America, long beyond musical maturity, deserves its say in a serious way.”

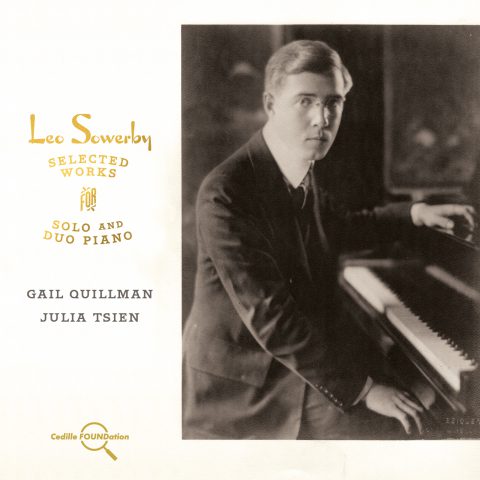

Leo Sowerby (1895–1968)

Trio for violin, violoncello and pianoforte (H 312) (1953)

Although born in Grand Rapids, on the other side of Lake Michigan, Leo Sowerby was the quintessential Chicago musician. His musical education, first successes, and long career as a composer, educator, church musician, and Pulitzer Prize winner (in 1946, for his cantata The Canticle of the Sun) were all associated with the city he considered his hometown. Sowerby came to Chicago as a 14-year-old to study piano. Not long thereafter, Sowerby’s compositions attracted the attention of Frederick Stock, principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In January 1913, Sowerby’s Violin Concerto was performed by the CSO. This was an extraordinary achievement for any American composer at a time when the majority of the orchestra’s members were European, and rehearsals were conducted entirely in German. And Sowerby was only 17 years old! Enlisting as a soldier during World War I, Sowerby served as an infantryman, then as clarinetist and bandmaster for the 332nd Field Artillery division. He returned to Chicago after the war and gained the support of Chicago philanthropist, pianist, and fellow composer Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, who had recently founded the Berkshire Music Festival where his Trio for Flute, Viola and Piano (H 149) was performed in 1919. After hearing Sowerby’s music at Berkshire, American musicologist Oscar Sonneck was heard to quip, “Who are the three Bs?” and answer himself: “Bach, Beethoven and SowerB!” Sonneck’s famously caustic wit likely intended a sarcastic pun on “sour,” but the implicit comparison to Brahms did not hurt the young composer’s reputation. In 1921, Sowerby was appointed the inaugural Music Composition Fellow at the American Academy in Rome, which led to advocacy of his works by conductors Serge Koussevitsky, Dmitri Mitropoulos, and Eugene Ormandy, among others. Returning to Chicago in 1925, Sowerby completed graduate work at the American Conservatory, then joined the composition faculty, serving from 1925 to 1962.

Sowerby’s celebrated tenure as organist and choirmaster of Chicago’s St. James Episcopal Church (later Cathedral) established him as one of the preeminent American composers of organ and choral music. His 500+ compositions, though, range from piano solos to large-scale orchestral works — and nearly every other imaginable genre except for opera and ballet. To date, relatively little attention has been paid to Sowerby’s chamber music, likely because most of it remains unpublished. The Trio for Violin, Violoncello and Pianoforte (H 312) was completed in 1953. The work is dedicated to Dr. James L. German, physician-scientist and pioneering researcher in human genetics who, according to his widow, was also a very fine pianist and organist. Sowerby often played chamber music with his friend while Dr. German was an intern at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital. German wrote to his wife in August 1953 that the Trio was Sowerby’s “best work” and that he was certain “it would become part of the permanent chamber music literature.”

The first movement, marked “Slow and Solemn,” opens with a pianissimo repeating pattern doubled in octaves, emanating from the lowest register of the piano. The muted violin soon joins in with a pseudo-fugal subject: a wandering melody that is, in turn, reinforced by the muted cello. The mood is not only solemn, but reverent. Layered melodies build in intensity, then abruptly switch to a faster tempo, marked “with verve,” as the violin and cello are featured in a variation of their melody from the opening of the movement. At times virtuosic, at times reflective, the continually evolving rhythmic and harmonic interplay between instruments is a hallmark of this work.

The second movement, “Quiet and serene,” opens with intertwined melodies of sustained double stops in the violin and cello, both muted; the effect is that of a freely-evolving organ prelude. The piano enters with its own expansive melody in open chords marked “belllike.” Transforming into a quiet ballad for violin and cello, the movement navigates through more insistent moods then ends as it began, with the ethereal sounds of sustained string harmonics against wideranging open octaves in the piano.

The final movement, marked “Fast; with broad sweep,” begins with energetic, perpetual motion rhythms in the piano, continuing the wide-ranging open textures of the previous movement. A march section enlists the violin and cello as the music ebbs and increases in dramatic intensity toward the final cadence.

With this recording, the Lincoln Trio emphatically stands with scholars such as Carol Oja who advocates for the revival of Sowerby’s music, calling the composer one of the “forgotten vanguard” of the 20th century: too conservative to merit the spotlight; too difficult to get to know. Sowerby himself once remarked that he had been “accused by right-wingers of being too dissonant and cacophonous, and by leftists of being old-fashioned and derivative.” Listeners in the 21st century, however, will find that no such labels are required as repeated close listenings to this exquisitely crafted music are continually rewarded with new insights.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded June 29–July 1, 2020, Murray and Michele Allen Recital Hall, DePaul University, Chicago, IL

Publishers

Bacon © 2001

Ernst Bacon Society

Sowerby © 1995

Leo Sowerby Foundation

Cover Photo

1950s Skyline of Michigan Avenue Buildings and Chicago Lift Bridge, Chicago Illinois

(r147 HAR001 Hars Old Fashioned) courtesy of ClassicStock / Alamy Stock Photo

Graphic Design

Bark Design

CEDILLE RECORDS © 2021

CDR 90000 203