Store

Store

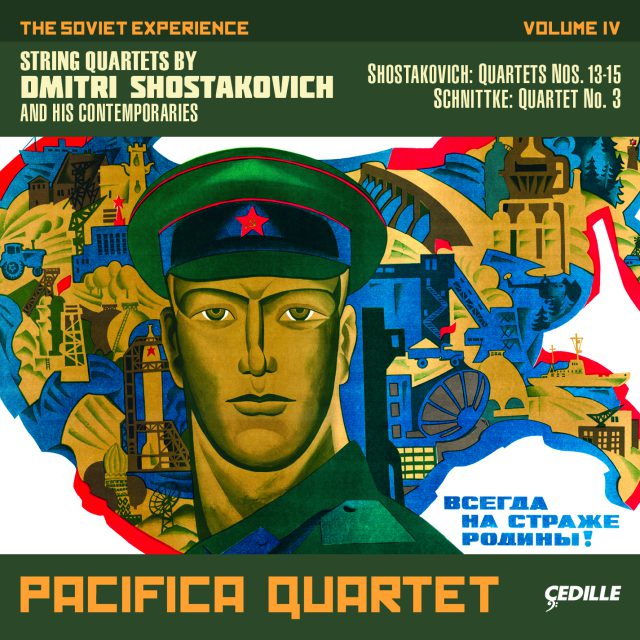

The Soviet Experience Volume IV: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries

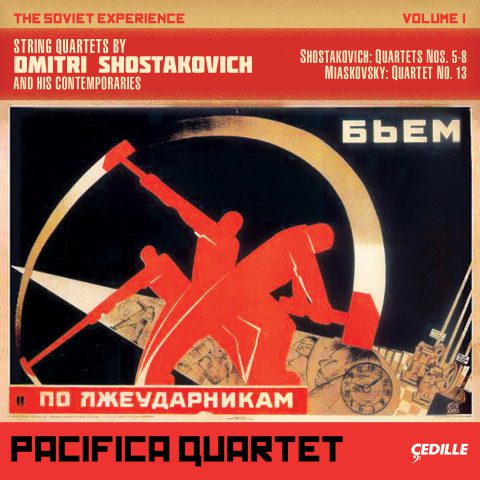

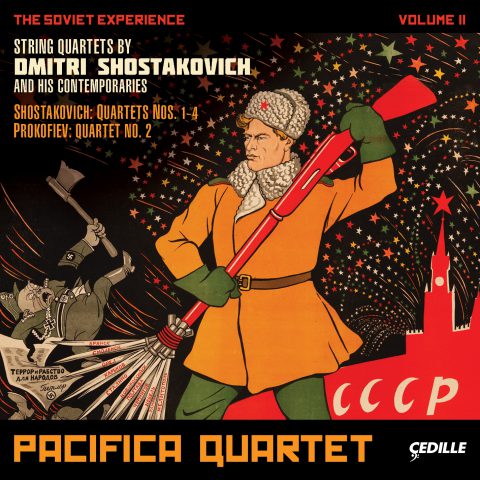

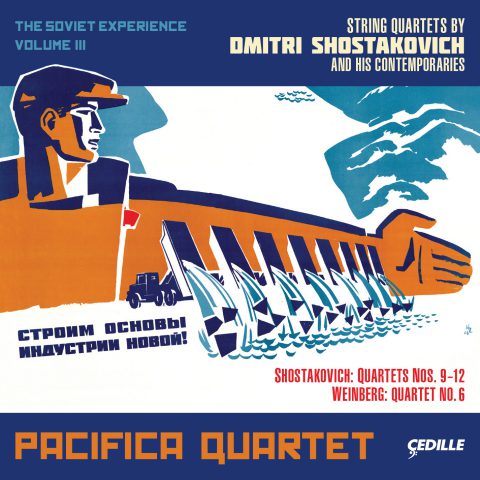

This is the final installment in the Pacifica Quartet’s highly anticipated, and already highly acclaimed four-volume CD survey of the complete Shostakovich string quartets: The Soviet Experience: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries.

The Soviet Experience Volume IV features Shostakovich’s String Quartets Nos. 13–15 from the 1970s. The Thirteenth Quartet’s one and only movement featuring extensive solo viola uses extended techniques uncommon for Russian composers at that time. The Fourteenth, composed in 1973 is a surprisingly upbeat work of 3 movements prominently featuring the cello. The Fifteenth is a meditation on mortality and one of Shostakovich’s longest quartets. These three quartets are paired with Schnittke’s allusive homage, String Quartet No. 3, written in 1983. It’s a work full of quotation including a 12-tone row transposed from a theme by Shostakovich, whose influence was felt throughout Schnittke’s career.

Preview Excerpts

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975)

String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat minor, Op. 138

String Quartet No. 14 in F-sharp major, Op. 142

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletShostakovich Quartets 13, 14 & 15

Schnittke Quartet 3

Notes by Gerard McBurney

The idea of Late Style has been much pondered. In his celebrated essay, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain, literary theorist Edward Said, then approaching his own end, observed:

The accepted notion is that age confers a spirit of reconciliation and serenity on late works, often expressed in terms of a miraculous transfiguration of reality….But what of artistic lateness not as harmony and resolution, but as intransigence, difficulty and contradiction? What if age and ill health don’t produce serenity at all?

Such thoughts come into sharp focus when we turn our ears to Shostakovich’s last three quartets. Although the composer was not especially old when he wrote this music — only in his 60s — he was assailed with health problems. These forced a daily awareness that his remaining time was short, and made even the physical act of writing music on paper painful and awkward.

Amazingly, these difficulties appear to have stimulated him creatively as much as they held him back. Unable to hold a pen for more than limited amounts of time, he seems (to judge by the music itself) to have set about internalizing the mystical action of composing with ever greater intensity. The imaginative result was a language that, if not completely distinct from that of his earlier music, unquestionably stands at an awkward and sometimes startling angle to it — a language indeed often filled with “intransigence, difficulty and contradiction.”

As we listen to these quartets, we might well be reminded of German musicologist Theodor W. Adorno’s famous description of the main characteristics of late Beethoven (as quoted by Said):

…[a] subjectivity that forcibly brings the extremes together in the moment, fills the dense polyphony with its tensions, breaks it apart with the unisono, and disengages itself, leaving… naked tone behind; that sets the mere phrase as a monument to what has been, marking a subjectivity turned to stone…

Caesuras… sudden discontinuities… moments of breaking away… [when] the work is silent at the instant when it is left behind, and turns its emptiness outward…

Shostakovich dedicated each of his 11th through 14th quartets to the individual members of the Beethoven Quartet, with whom he had worked closely for decades. The 13th was his gift for the Beethovens’ violist, Vadim Borisovsky. Like its predecessors, it includes tributes to both the instrument and the artistry of the dedicatee — in particular, beginning and ending with long solos written with Borisovsky’s personal style of playing in mind. The first of these solos roots the subsequent sound of the whole quartet in the rich, somber world of the viola’s lower strings. The second, as though under the impact of the musical and psychological traverse of the whole composition, ends by climbing towards the highest and most fragile sounds of which this most paradoxical of instruments is capable.

From earliest youth, Shostakovich had shown a fascination with the compositional possibilities of music referring to other music, whether by quoting from his own or other composers’ pieces, or by parodying different styles and ideas, sometimes angrily, sometimes comically or even affectionately. In the rarified world of his later music, however, this old creative habit undergoes a subtle change. Intertextual references, while still ubiquitous and recognizable, now become ethereal, elliptical, etiolated, and allusive. We hear this in the opening of the 13th Quartet, where three ideas are presented, one after another, each fraught with shadowy suggestions of other worlds and each with its own distinctive character.

First comes that dedicatory viola solo, a lamentation formed from a 12-note row, although most listeners will hear it rather as a series of interlocked descending chromatic scales, like sobs fading into the distance. Shostakovich toyed with 12-note rows often in his later works, but he never treated them as true rows in the manner of Schoenberg and his pupils. He instead preferred to use them, as he does here, as quarries for shorter motifs with which to unify long paragraphs of music, and also as a way of opening up the remotest tonal spaces to be explored in the music to come.

To this opening lament the whole quartet responds, almost in the manner of a church chorus answering the incantation of a precentor or priest. Harmony, spacing, and melody all suggest religious music. It is a curious aspect of Shostakovich’s late style that, while he showed little interest in religion in his daily life, the sound of religious music gained increasing importance in his compositions.

After another brief solo, from the first violin but echoing the viola’s opening, the second violin introduces a third idea, also evocative of Russian Orthodox chanting but, more importantly and strikingly, alluding to one of Shostakovich’s favorite works of Russian music: Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov. The reference is to Boris’s famous death-scene, and the haunting moment when the heart-broken Tsar tells his young son how to govern Russia wisely once Boris has died.

Overall, the 13th Quartet takes the form of a single movement in the shape of an arch: a slow introduction leading to a quicker central section, like a scherzo or dance of death, and then a return to the opening slow music. The central section — prancing, mocking, and marked doppio movimento — is initiated by a little rhythmic motif in the first violin. In the composer’s 14th Symphony, completed a year earlier, this motif was used to set words by Guillaume Apollinaire conveying a woman’s bitter reaction to the slaughter of the First World War:

Khokhochu! Khokhochu!

I laugh… laugh… at the beautiful loves cut down by death

The restless texture of this central section of the quartet is also richly polyphonic. Shostakovich was one of the contrapuntal masters of the 20th century and here he finds a whole variety of spidery and delicate ways to combine wraiths and echoes of his opening three ideas. He also introduces new imagery, including the hollow sound of the stick of the bow tapped against the rounded underside of the body of the instrument, like someone tapping gently on the lid of a coffin (a rare instance of Shostakovich employing an “extended technique”).

The same ghostly tapping continues into the slow final section of the quartet, when the three themes of the opening reappear but none quite as we heard them at the beginning. Each has been transfigured by the experience of the intervening dance of death.

Shostakovich’s 14th Quartet completes his cycle of four hommages to the Beethoven Quartet with a large-scale three-movement work dedicated to the Quartet’s cellist, Sergei Shirinsky. From its first notes this piece establishes a quite different tone from that of its predecessor. While the 13th Quartet (1970) prompts comparisons to the 14th Symphony of 1969, the 14th Quartet (1973) presents parallels with the 15th Symphony (1971). In particular, the quartet’s first movement continues and explores further the childlike, playful quality of the opening movement of the 15th Symphony, which the composer likened to a “toyshop.”

Also as with the 15th Symphony, the 14th Quartet contains many echoes of the music of Shostakovich’s own youth, some delightful, some painful. These revolve especially around pieces that held special autobiographical significance for him, such as his First Symphony (1925) and the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1932).

Take the jaunty opening tune for the cello (the dedicatee’s instrument). This is strikingly similar in style to some of the more mocking passages from Lady Macbeth and other theatre scores from the 1930s. How Shostakovich treats the tune in this quartet, however, is far different from what he would have tried 40 years earlier. Out of what seems a deliberately unpromising and trivial phrase, he builds not satire but one of the most delicate, unpredictably whimsical and subtle musical structures of his final years. Filled with Adorno’s “sudden discontinuities” and “moments of breaking away,” it traces a labyrinthine harmonic journey from the opening key of F-sharp major (one of the trickiest for Western stringed instruments) through a whole series of unexpected secondary keys (which he makes feel even more remote than they really are) back to F-sharp major at the end.

The central slow movement, by contrast, offers one of Shostakovich’s starkest visions: a contorted solo line for the unaccompanied first violin, more like the painful recollection of half-forgotten scraps of melody than anything we would normally call a tune. A while later, the cello takes up the same solo line, and the first violin gives the impression of improvising counterpoint above it. This again sounds more like an aggressive attack on the original concept than anything resembling normal polyphony; one might describe it as anti-counterpoint.

The central section of this movement reinvents itself as a ghostly serenade, beginning with a leering cello melody supported by a plucking, guitar-like accompaniment from the other three instruments. The melody unexpectedly transforms itself into a swaying, off-center waltz in a distorted 19th century style. Here the first violin joins the soaring, swooning cello tune at the interval of a sixth below to create a syrupy texture and deeply poignant harmonic color.

This memorable moment feels strikingly like a quotation of a scrap of olden music, even though there never was an olden music quite like this. Violist Fyodor Druzhinin, who joined the Beethoven Quartet in 1964 and played the first performance of the 14th, recalled a moment in rehearsal when the composer, referencing this episode, asked the musicians, “How did you like my Italian bit?”

Druzhinin assumed the composer was making an association between this moment and a once-famous piece of cheap and popular Italian music from the 19th century, Gaetano Braga’s Angel’s Serenade. Druzhinin knew (it was an open secret in Moscow) that Shostakovich, at this late period of his life, was dreaming of writing an opera on Anton Chekhov’s short story, The Black Monk. In that haunting tale, Braga’s melody is heard several times by the protagonist who, in his suffering and despair, comes to view it, in all its treacliness, as a memento mori (a reminder of the inevitability of death), both sweet and terrifying.

The final movement begins with more plucking: a numbed pizzicato tapping of what seem at first to be random notes, once again hardly a melody at all. This time, however, there’s a clue: the names of the notes spell the letters:

S-E-Re-E-G-A

… a familiar form of Sergei, the first name of the dedicatee.

The music that follows starts out as an urgent scherzo-finale, perhaps another dance of death as in the 13th Quartet. But, as so often with Shostakovich, the composer surprisingly, the music’s energy ebbs away and we hear the cello, on its lowest string, make a second reference to the same first name, using one of the most famous and poignant phrases from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. It is the moment when, on their journey to punishment in Siberia, the stricken heroine, Katerina makes a final, desperate attempt to win back the affections of her feckless lover:

Serezha! O milyi moi!

Sergei! Oh, my dear one!

This heartfelt appeal marks a crisis in the quartet’s structure. Where we might have expected the fast music to continue, we are instead dragged back into the painful bleakness of the slow movement (including a return of the “Italian bit” toward the end). The result is to give this second half of the 14th the illusion of an arch-shape reminiscent of the overall form of the 13th. But again we are deceived. At almost the very end, as with the conclusion of the 15th Symphony, the music changes yet again, this time plunging us into an entirely unexpected world of luminous harmonic simplicity — a different kind of music that sounds as though it could have been written a hundred years earlier.

As the composition of his quartets unfolded over nearly 40 years, starting with the First in C major of 1938, each addition to the cycle appeared in a different key. Shostakovich’s contemporaries report that he began to dream of a complete set of 24 quartets in all the different keys. He did not live long enough to achieve such a result, of course, but one effect of his dream is that nearly all of his late quartets are in “remote” tonalities. Remote in that they are on the far end of the circle of fifths from the cycle’s opening C major; and also remote because these are keys that offer fascinating problems of pitch and intonation to string players. Violins, violas, and cellos are traditionally constructed to resonate to, and therefore be kept in tune with, the so-called “simpler” keys — F, C, D, G and the like. When a composer uses keys that force the players to spend time with their fingers on the “black” keys (in piano parlance), he can exploit this to give the music an aura of greater fragility and vulnerability (Shostakovich’s musical idol, Gustav Mahler, was fond of this effect).

Shostakovich’s final quartet, the 15th of 1974, is a potent and deliberate example of this. Not only is it in six continuous movements, but every movement is in the same extremely difficult key of E-flat minor and every movement is slow. So those beautiful moments of fragility and vulnerability are inevitably highly audible; they’re never covered up by fast playing or a shift into an easier key.

There’s another fascinating aspect of the 15th too, found in the way it draws together the 13th Quartet’s religious and liturgical elements with the quotations and self-references of the 14th, and then adds an additional element: a sense of near-amorous proximity to a range of familiar masterpieces by composers of the past. The great ones of the baroque and classical period hover over this composition in a more striking way than almost anywhere else in Shostakovich’s output (his final work, the Viola Sonata, Op. 147, with its quotations of the “Moonlight Sonata” being the other obvious example), almost as though he were saying farewell to the music of the past he loved so much.

The unusual form itself seems to point to some pretty remarkable models. The idea of six slow movements in succession suggests the famous seven successive slow movements of Haydn’s Seven Last Words of Our Savior on the Cross; and something akin to the dramatic structure of the Haydn is also proposed by the (completely non-religious) titles Shostakovich gives his movements: Elegy—Serenade —Intermezzo—Nocturne—Funeral March—Epilogue. Clearly, we are being asked to imagine a mysterious hidden ceremony or story, haunted with elements of love and death.

The idea of a series of seamlessly linked movements, and the spareness of the slow opening fugato, together with the remoteness of the key, also brings to mind one of the greatest masterpieces of the entire string quartet repertory: Beethoven’s Op. 131 in C-sharp minor. And the theme of the fugato, despite its liturgical character, seems distinctly reminiscent of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden Quartet.

Liturgical echoes continue in the Elegy with two more chantlike themes. The first is close to the traditional Russian Orthodox Alleluia that greets the Easter Resurrection. The second — played in pianissimo two-octave unison by the second violin and cello — recalls the famous Vechnaya pamyat’ (Eternal Memory), the ancient funeral chant from the same tradition.

The ascetic second movement, Serenade, begins with another of Shostakovich’s 12-note rows, passed like a series of shrieks from one instrument to another, and answered by hollow strumming, like that of an out-of-tune guitar. Evidently, this serenader — an even more sinister example of the serenader from the second movement of the 14th Quartet — has a more than passing connection to that old leering woodcut figure of a skeleton with an instrument in his hands, singing beneath the window of a doomed maiden, not only as described by Schubert (as we have just been reminded) but also in one of Shostakovich’s best-loved Russian works, Musorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death.

Halfway through the third movement, Intermezzo, after a whirlwind cadenza, the first violin launches without warning into a mysterious high melody. Its first three notes—a distinctive trope characteristic of certain 19th century Romantic composers—is reminiscent of the opening of the slow movement of the 14th Quartet, and of Shostakovich’s use of the same musical image in the finale of his 15th Symphony. There, he uses it to create an eerie, even creepy musical pun between the opening of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde and the melody from Glinka’s song setting of the poem, “Dissuasion,” by the Russian Romantic poet Yevgeny Baratynsky:

Do not tempt me needlessly with the return of tenderness…

There are many such half-references and allusions in this great final quartet of Shostakovich; the music is astonishingly rich with them. But perhaps the most important and most moving comes in the very closing bars. This dying away of music we recognize from the Quartet’s Funeral March fifth movement, is a transcription of the final bars of another Shostakovich masterpiece written 35 years earlier and one of the greatest achievements of his youth: the first movement of his 6th Symphony.

The next generation of Soviet composers after Shostakovich — a fascinating group including Edison Denisov, Sofia Gubaidulina, Alfred Schnittke, Arvo Pärt, and Valentin Silvestrov—are remarkable for the way they set about defining their own voices. They came to maturity almost immediately by establishing themselves in sharp stylistic opposition to Shostakovich. This was only natural. Coming to independence in the late 1950s —the period of relative cultural freedom known as the Khrushchev Thaw — these young men and women urgently needed to free themselves from the artistic authority of their elders. Their instinct was to do that by looking outside the constricted world of Soviet music for models and inspiration. They were especially excited by composers whose music was still forbidden in the USSR at that time, including Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, and post-war European and American avantgardists such as Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti, and Cage.

With time, however, many of these younger composers ended up returning to Shostakovich in later years, sometimes even re-examining his style and ideas through the prism of their own compositional approaches. This was particularly true of Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998).

Listening to Schnittke’s ground-breaking music from 1960s, one would be hard put to identify any Shostakovich influence, except perhaps for a certain kind of tragic rhetoric that was very much part of all serious Soviet culture of that period. While Schnittke’s 1st Quartet of 1966 does use 12-note rows, in parallel with Shostakovich’s concurrent fascination with this musical idea, the younger man employs his rows in a manner more like the 12-note music of Schoenberg or Berg than that of Shostakovich.

A first overt musical acknowledgement of Shostakovich came when Schnittke marked the death of the older composer in 1975 with the touching Prelude in memoriam Dmitri Shostakovich for 2 violins. From that moment on, echoes of Shostakovich begin to creep more frequently into Schnittke’s music. Despite this, there is little that sounds like Shostakovich in Schnittke’s 2nd Quartet of 1981. The piece is filled with religious imagery derived from early Russian church music, but the effect is far from the chants found in Shostakovich’s late quartets.

When Schnittke composed his 3rd Quartet two years later, however, matters had clearly changed. This imposing work in three movements, slow-fast-slow, immediately suggests a Shostakovichian arch-structure (shades of the 13th and 14th quartets). It begins with three quasi-quotations, an almost precise parallel with the three stylistic references at the beginning of Shostakovich’s 13th and 15th quartets: first, a descending pair of 16th century-style cadences the composer marks “Orlando di Lasso — Stabat Mater,” although Schnittke extracts an essence from Lassus’s great work rather than quoting the original exactly. Next, the angular, chromatic main theme of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, Op. 133, but again not exactly as we hear it in Beethoven. Finally, growing directly out of the Beethoven quotation, the famous DSCH signature motif of Shostakovich (D–E-flat–C–B natural), but recast as a kind of scream (with the notes always rising), very unlike the many occurrences of this 4-note image in Shostakovich’s music.

Shostakovich is thus (albeit in a twisted and distorted form) placed right at the heart of Schnittke’s 3rd Quartet, alongside Beethoven and Lassus (a master of the European Renaissance). Clearly, some sort of statement is being made.

Out of these three scraps of material, Schnittke fashions in his first movement a densely woven sound fabric combining and recombining the three ideas so that they transform and begin to suggest a profusion of new ideas.

Schnittke seizes upon one of these new ideas to establish the main theme of the Agitato central movement. It is a curious and (typically for Schnittke) paradoxical musical image that begins surprisingly like a minor key rondo theme from Mozart, early Beethoven, or Schubert. It feels like we are leaping into yet another period of the past. But instead of developing this idea or transforming it, Schnittke simply repeats it over and over, while aggressively interrupting it with harsh, expressionist shrieks and cries. Throughout this uproar, Schnittke keeps driving the music back toward the original Lassus, Beethoven, and Shostakovich.

Schnittke’s third and final movement also contains parallels with Shostakovich. It begins as a funeral march, with the same four-square dotted rhythm Shostakovich uses for the 15th Quartet’s march. But Schnittke changes the sense of this association by smearing the harmonies so that his march recalls not the nobility of Shostakovich’s piece, but rather the heavy vulgarity of the official Soviet funeral march (employed at the innumerable rituals of mourning and state funerals that made up so much of the liturgy of Soviet public life).

Out of this darkness and bitterness, the original three ideas from the beginning—Lassus, Beethoven, and DSCH—begin to reappear, but now fragile and fading back into the distance.

Noted scholar of Russian and Soviet music, Gerard McBurney is Artistic Programming Advisor for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Creative Director of its acclaimed Beyond the Score Series.

Album Details

Total Time Disc One: 45:12

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman:

Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing Bill Maylone

Editing Assistance: Jeanne Velonis

Recorded: Shostakovich Quartets Nos. 13 and 14: December 16–18, 2012; Shostakovich Quartet No. 15 and Schnittke Quartet No. 3: August 24–26, 2013—Auer Hall, Indiana University Bloomington

Microphones: Sonodore RCM-402 & DPA 4006-TL

Front Cover Design: Sue Cottrill

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card: Nancy Bieschke

Front Cover Art: Always on the guard of Homeland!, 1973, by V. Chumkov — available at www.sovietposters.ru

Publishers:

Schnittke Sikorski —String Quartet No. 3, Op © 1983 (SIK6752)

Shostakovich Sikorski — String Quartet No. 13, Op. 138 © 1970 (SIK2170); String Quartet No. 14, Op. 142 © 1972 (SIK2175); String Quartet No. 15, Op. 144 © 1974 (SIK2204)

© 2013 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 145