Store

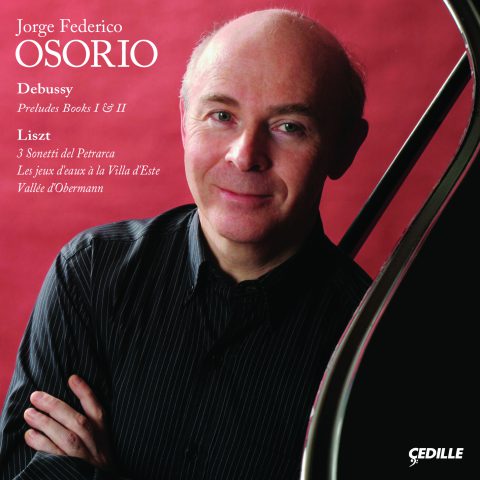

Distinguished international pianist Jorge Federico Osorio brings his flair for French music to works of the Baroque, Romantic, and early 20th century eras by Jean-Philippe Rameau, Emmanuel Chabrier, Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel.

Fittingly, Osorio opens The French Album with Fauré’s exquisite Pavane and concludes with the ever-popular Pavane pour une enfante défunte by Fauré’s student, Ravel.

The Mexican-born, European-trained pianist, who studied at the Paris Conservatory with Bernard Flavigny and Monique Haas, offers eight of Debussy’s pictorial Préludes, each with its unique sound world, including the mystical La Cathédrale engloutie, one of the most stunning pieces ever composed for piano. Another audience favorite is Debussy’s evocative Claire de lune from his Suite bergamasque. Providing contrast, Rameau’s whimsical Les Tricotets conjures the back-and-forth motion of knitting needles.

A set of Spanish-flavored works include Chabrier’s Cuban-inspired Habanera; Debussy’s lively La Puerta del Vino, depicting sailors carousing and enjoying their wine, and La soirée dans Grenade, where the piano imitates the sound of a guitar; and Ravel’s Alborado del gracioso, brimming with Iberian rhythms.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Jorge Federico Osorio on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845–1924)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918)

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683–1764)

EMMANUEL CHABRIER (1841–1894)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe French Album

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

In the 16th century, the pavane — a genre that opens and closes this program — emerged as an Italian courtly dance, of the formal two-steps-forward-one-step-back pattern for partners who touched only each others’ hands. It made its way into non-dance areas, being used in lute and keyboard music. By the late 19th century, it had become redefined as an evocation of things past, and perhaps the formality of traditional Spanish court customs led to its particular association with that country. (Both Maurice Ravel and choreographer Léonide Massine associated it with the paintings of Diego Velasquez.)

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924) wrote his Pavane, Op. 50, for solo piano in 1887. His orchestration from later that year may be the more familiar version today, but the piece is exquisite in its original form as a work for solo keyboard. There are Spanish echoes but most evident is Fauré’s astonishing melodic genius, heard so clearly in his solo songs and in the reverent, hushed Requiem Mass.

It took Fauré a long time to earn his living from composition; fortunately, he was a first-rate organist who supported himself with church posts. Also a pianist and teacher, he headed the Paris Conservatory from 1905 to 1920. Perhaps ironically, his appointment was precipitated by a scandal that involved one of his students, Ravel, who’d been repeatedly denied the prestigious Prix de Rome by the hidebound Conservatory faculty. Fauré, initially regarded as a compromise candidate for the top post, energetically reorganized the institution. This Pavane further links him with his student, both of them part of the broad, highly varied, and most distinguished historical path of French keyboard music.

Claude Debussy (1862–1918) was fascinated by the sheer sound of the piano: its whole extended range from highest to lowest, the ways its pedals can change the tone color, the brilliance to be achieved with fast runs, the power of huge chords, all the resonance of this very powerful instrument. This fascination with piano sonority seems to have inspired the creation of his two books of Préludes at least as much as any poem or picture referenced in the preludes’ titles. In fact, he placed the titles at the end of each piece, not the beginning, suggesting that they were, to some extent, afterthoughts. They can be heard as experiments in sound: what are the possibilities of chromatic harmony and non traditional scales? How can Spanish-guitar sounds, musichall tunes, and dance rhythms be incorporated into keyboard miniatures? What colors can the black-and-white keys call forth in the listeners’ imaginations?

The titles come from myriad sources as varied as sculpture, drawings, legends, nature, dance, and poets from Shakespeare to the French symbolists. On this CD we hear eight preludes, drawn from both books, plus two Debussy pieces taken from his other suites and collections.

Virtually everyone knows Debussy’s “Clair de lune,” more evocative of moonlight than even Beethoven’s famous sonata. It comes from Suite bergamasque, which Debussy wrote in 1890 and revised 15 years later. The suite’s title appears to come from a line by French poet Paul Verlaine, alluding to singers and dancers doing “masques et bergamasques.” The term originated as a reference to folk music characteristic of the Italian city of Bergamo.

“Voiles,” from the first book of Préludes, may be translated either as Sails or Veils, but whichever you envision, the music exudes a sense of mystery, attributable to Debussy’s use of two unconventional scale patterns that crop up in both volumes. The whole-tone scale creates an exotically amorphous, unresolved sound (produced, for example, by playing C followed by D, E, F , G , and B ). Since each interval is equal, no one tone stands out. Then there’s the pentatonic scale (C, D, E, G, A, for example) used in the middle-section, a pattern that appears in Native American, Anglo-American, Eastern European, and Asian folk and art music. (Debussy probably first heard the scale played by an Indonesian gamelan ensemble at the Paris Exposition of 1889.) “Les collines d’Anacapri,” also from Book 1, has a much more extroverted mood and a song-like middle-section, such as might come from a folk tune as rippling figurations lead to a brilliant passage in the piano’s high register. “Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest” (What the West Wind Saw) includes “tumultuous” in its tempo marking, and its atmosphere is indeed powerful and threatening. Perhaps the west wind saw storms on the way. Penetrating trills and powerful chords dominate the texture; dissonant bass register

crashes are contrasted with complex figures in the higher register. Some say the title evokes a Hans Christian Andersen story, “The Garden of Paradise,” wherein the four winds tell of what they’ve seen. Another suggestion is that it derives from Percy Bysshe Shelley: “O wild west wind, thou breath of autumn’s being… Wild spirit, which are moving everywhere.”

“La Cathédrale engloutie,” with its vivid imagery, is one of the most stunning pieces ever composed for the piano. There is a legend in Brittany, on the northwest coast of France, about a city named Ys that sank beneath the ocean, but whose mighty cathedral can sometimes be seen rising from the waves, only to sink again. Subdued chords, which

open the prelude and continue underneath as the melody gradually emerges, represent the cathedral’s bells as it slowly comes into view. The tempo marking is “calm” and the harmonies are based on the pentatonic scale. The dynamic level builds until the cathedral is completely visible (fortissimo). Rumblings in the bass as the theme drops from higher registers to mid-range, show the sea reclaiming its own… and then the ghostly vision is gone.

From Préludes Book 2, we have “Feuilles mortes” (Dead Leaves). The leaves fall slowly, in no particular pattern, reminding us that winter is on the way. This is a slow-paced lament for the dying of the year, expressed through indeterminate harmonies. “La Puerta del Vino” (Wine Port), picks up the pace with its habanera (Cuban) syncopated accents and evocation of sailors at dockside dancing and clutching wine bottles. There are traces of the odd intervals of another unconventional scale, the Arabic (start with C but go to C instead of D, then to E.) (This piece is placed later in the program as part of a “Spanish” set with Chabrier’s “Habanera,” Debussy’s “La soirée dans Grenade,” and Ravel’s “Alborada del gracioso.”) The quiet radiance and resonant chromatic harmonies that open “La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune” lead to a brilliant sonic display representing moonlight emerging from behind clouds. Then the haze returns, obscuring the moon again. “La terrasse des audiences” may be translated as Balcony, or some other kind of platform from which a monarch could survey his subjects. But the ruler here seems to be the moon: Is it the moon that’s holding court? The last of Debussy’s preludes, and the most directly exciting, is “Feux d’artifice” (Fireworks). This uses the entire range of the keyboard and the power of the sustaining pedal to depict a colorful pyrotechnic display against the night sky. In keeping with the topic, there are echoes of “La Marseillaise.” After the final display, we hear the fireworks die out as the sound slowly fades.

Last from Debussy on this program we have “La soirée dans Grenade” (Evening in Granada), from his 1903 collection Estampes (Prints). Again the Arabic scale is heard, and the composer has the piano imitate the sound of a guitar. Granada is home to one of Spain’s major historical landmarks, the Moorish palace called the Alhambra. Perhaps the guitar sounds are echoing through its moonlit gardens.

Jean-Philippe Rameau was born in 1683, making him a close contemporary of three other Baroque giants: Bach, Handel, and Domenico Scarlatti (all born in 1685). At his zenith, Rameau was the most celebrated opera composer in France. By the time of his death in 1764, however, he was regarded as old-fashioned, and his music entered long years of eclipse. He excelled in two realms, that of opera and the opera-ballet — many written for the royal courts of Louis XIV and Louis XV — and that of keyboard music. He published three volumes of Pièces de Clavecin (Harpsichord Pieces). He also won fame as the author of a Treatise on Harmony, published in 1722. His first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie — drawn from Greek mythology, as so many Baroque operas were — was mounted in 1733. From then on he seldom came back to writing for solo harpsichord, although in the 1740s he came out with a group of Pièces de clavecin en concerts for keyboard and chamber ensemble.

His third collection of harpsichord pieces, probably dating from 1725 and 1726 (scholars quarrel about the year) contains the word Nouvelles (new) in its title; one thing that was not new is that the pieces are organized into suites according to their key. Jorge Federico Osorio has chosen three short pieces from the Suite in G (either major or minor). Something that might be considered “new” is the frequency of descriptive titles for the pieces, for example, “Les Tricotets.” The French verb tricoter means to knit, and this light-hearted little rondo (Fr: rondeau) features rhythmic patterns exchanged between the right and left hands that suggest the back-and-forth motion of knitting needles. Then we have a gentle Minuet in G. The minuet was a triple-meter 8 dance style widespread in 18th-century courtly circles, moderately paced and very elegant. This one is a decided contrast to its successor, “L’Egyptienne,” or “The Gypsy Girl.” (The Roma people do not come from Egypt, of course, but were thought to in the 18th century.) This evocation is dramatic and virtuosic, quite chromatic, with richly-embroidered melodic lines.

In the late 19th century, several French composers re-discovered Rameau’s works after they’d suffered in obscurity since the time of the 1789 French Revolution. Among these were Vincent D’Indy, Camille Saint-Saëns, Paul Dukas — and Claude Debussy. The prominence of Debussy, Ravel, and Fauré in late 19th-century French music has somewhat obscured the career of Emmanuel Chabrier (1841–1894), although all three of them acknowledged Chabrier’s talents and his position as a kind of catalyst, a link between musical tradition and the innovations of the French Modernists. At the insistence of his family, Chabrier studied law in Paris and held a position in France’s Ministry of the Interior for 19 years. He composed evenings and weekends, and became friends with poet Paul Verlaine and Impressionist painter Edouard Manet. After 1880, he devoted himself to composition full-time. Besides the well-known orchestral rhapsody España, he composed operas, piano music, and songs. The same trip to Spain that gave him the inspiration for España also brought forth his 1885 piano “Habanera.” The Habanera, named for Havana, Cuba, is a 19th-century song and dance style, on the slow side, usually in a duple meter such as 2/4. It traveled first to Spain, then elsewhere in Europe. The repeated rhythmic pattern is characteristic: a dotted pair followed by two “even” notes. This pattern is clearly heard at the start of the most famous habanera of all, Carmen’s first aria in Act I of Georges Bizet’s opera. It’s prominent in Chabrier’s piece too.

We’ve already heard Spanish influence in Chabrier’s “Habanera” and in many of Debussy’s pieces. A fascination with the culture of Spain was characteristic of many French composers at the turn of the 19th century and in the early years of the 20th. One particularly fascinated composer was Maurice Ravel (1875–1937). Although he studied piano from the age of seven, and won a piano-performance prize during his first year at the Conservatoire, Ravel (1875–1937) did not regard the piano as a central factor in his artistic life, being always more focused on advancing his career as a composer than on performing. One of his best friends, however, was the pianist Ricardo Viñes (1875–1943), whose virtuosic skills and country of origin (Spain) made him a soulmate who influenced the course of Ravel’s piano writing. Viñes premiered most of his friend’s keyboard works, which are remarkable for their technical challenges, particularly the suite Gaspard de la nuit.

“Alborada del gracioso” (Morning Song of the Jester) is the fourth of the five pieces in Ravel’s piano suite Miroirs (Mirrors), whose titles conjure up visual images but at a degree of separation: they’re not seen directly, but as reflected in a mirror. Even in Ravel’s most 10 intensely emotional music, one can often detect a kind of detachment, a one-step remove. Miroirs was completed in 1905, and Ravel orchestrated “Alborada” in 1918 (it’s perhaps more familiar in that symphonic version). The technically complex keyboard score is full of Spanish-style rhythms and themes, while the key is D minor leading to D major.

Ravel wrote his “Pavane pour une infante défunte” (Pavane for A Dead Princess) in 1899, while he was still studying under Fauré at the Paris Conservatory. He orchestrated it in 1910, and it’s this later version with which we’ve become more familiar. The title of Ravel’s piece is probably better translated as “Pavane for a Long-Ago Princess” rather than “dead princess.” The composer said, “A little princess might, in former times, have danced [this] at the Spanish court.” Along with the timeless work by his teacher, Ravel’s beloved Pavane frames our program and brings it to a poignant conclusion.

Album Details

PRODUCER James Ginsburg

ENGINEER Bill Maylone

RECORDED January 14–15, 2020, Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago

COVER IMAGE Camille Pisarro: Boulevard Montmartre (1897) State Hermitage Museum

PHOTO CREDITS Cover: Scala / Art Resource, NY. Headshot, page 12: Todd Rosenberg

GRAPHIC DESIGN Bark Design

STEINWAY PIANO

TECHNICIAN KEN ORGEL

© 2020 Cedille Records

CDR 90000 197