Store

While the classical era is synonymous with Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, Songs of the Classical Age illuminates a host of other composers of the Age of Enlightenment, along with less-familiar works by the aforementioned titans.

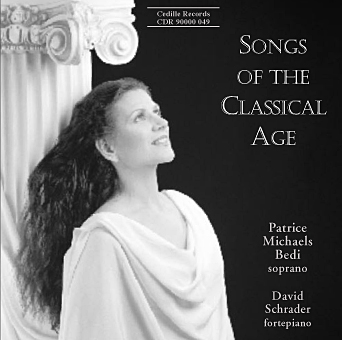

Soprano Patrice Michaels, with keyboard artist David Schrader on fortepiano, performs an exceptionally wide-ranging program of 27 songs in four languages by 17 composers, including seven women and a Black composer from the French Caribbean. On this CD, a companion to her previous recital disc, Songs of the Romantic Age, Ms. Michaels turns to what many consider her “core” repertoire: the music of Mozart and his contemporaries.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ JOSEF HAYDN (1732-1809)

VINCENZO RIGHINI (1756-1825)

CHEVALIER DE SAINT-GEORGES (1745-1799)

NICOLA DALAYRAC (1753-1809)

GIUSEPPE MARCO MARIA FELICE BLANGINI (1781-1841)

ANNA AMALIA VON SACHSEN-WEIMAR (1739-1807)

JOHANN FRIEDRICH REICHARDT (1752-1814)

CORONA SCHRÖTER (1751-1802)

MARIA THERESIA VON PARADIS (1759-1824)

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

SOPHIE WESTENHOLZ (1759-1838)

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

PAULINE DUCHAMBGE (1778-1858)

FELICE BLANGINI

MARIA SZYMANOWSKA (1789-1831)

ISABELLA COLBRAN (1785-1845)

MARIA SZYMANOWSKA

VINCENZO BELLINI (1801-1835)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletSongs of the Classical Age

Notes by Patrice Michaels

“Song . . . a short metrical composition, whose meaning is conveyed by the combined force of words and melody.” These words by Mrs. Edmund Wodehouse from an early edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians offer profound simplicity and provocative challenge. The 27 selections in Songs of the Classical Age represent the era’s range of verse, melody, and harmony, but they also point to trends in earlier and later vocal music. Before the Classical period, Medieval Troubadours and a few Renaissance composers excelled at self accompanied vocal music that could transmit a wide range of poetic sentiment. Composers of the Baroque era were more interested in creating cantatas stringing together many short movements, each one depicting a single affect. At that time, the preferred accompaniment to the voice was lute, organ, or harpsichord grouped in continuo with viola da gamba or cello. While most households retained the harpsichord well into the 19th century, the introduction of the fortepiano was a stunning innovation for Classical composers and performers. The variety of color and dynamic possibility on a fortepiano was entirely new, and it is to this relationship of instrument and voice that we owe our Classical and Romantic recital song aesthetic.

Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809) went to London for the first time in 1791, earning immediate popularity with his operatic, symphonic, and chamber music. By 1795, with his reputation established and his works regularly presented, Haydn enjoyed the kind of success that enticed many foreign musicians to remain. Two factors led him to curtail his stay in London, leaving posterity only a small collection of songs in English. England’s war with France made it nearly impossible to engage the Italian singers upon whom Haydn relied. And as court composer to the Esterházy dynasty, Haydn was summoned when Prince Paul Anton died unexpectedly. Haydn finished the London concert season of 1795 and returned to Austria, bringing with him the inspiration to compose Austria’s national anthem and the oratorio The Creation.

The canzonettas presented here owe their existence to a happy circumstance. In Vienna, Haydn frequently attended salons at the home of the imperial physician. In London, he lived near the royal physician, Dr. John Hunter, whose wife, Anne Home Hunter, was renowned for her frequent soirées and Scottish national verse. Whether high art or not, Haydn found Mrs. Hunter’s homely sentiment and domestic themes ideal for song settings. In Fidelity, he develops virtuosic solo lines for both keyboard and voice; in Sailor’s Song, witty repetition of motives prevails; and Pleasing Pain demonstrates his preoccupation with proportion and balance. The opening song in these selections from the Twelve Canzonettas is one of only SONGS OF THE CLASSICAL AGE 3 two texts not attributed to Anne Hunter. She Never Told Her Love is an excerpt from Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare (Act II, scene IV: Viola to the Duke).

Vincenzo Righini (1756-1825) wrote opera, sacred and instrumental music, approximately 200 songs, and an important book on singing. Originally a singer in his native Bologna, he joined an opera troupe in Prague, and wrote his first stage work in 1776. He became established as a composer and moved to Vienna four years later, where he was sought after as a singing teacher. Among his students were Maria Theresia von Paradis and Princess Elizabeth of Württemberg. In 1787, he became the first Italian-born Kapellmeister at the electoral court in Mainz. In 1793, he accepted offers to act as Kapellmeister and director of the Italian Opera in Berlin, working with J.F. Reichardt. The group of songs presented here is solid proof of his stature as a composer for voice. Or che il cielo (“Now that Heaven”), for example, could easily be taken for Mozart (who was born five days after Righini) in its lyricism, architecture, and beauty of accompaniment. Other songs in this group display brilliant handling of simple forms such as the A-B-A-Coda of Placido zeffiretto (“Gentle Zephyr”) and the playful, slightly extended structure of Vorrei di te fidarmi (“I Would Like to Have Faith in You”).

Chevalier Joseph Boulogne Saint-Georges (1749-1799), Nicola Dalayrac (1753-1809), and Giuseppe Marco Maria Felice Blangini (1781- 1841) all found success in the salons and theaters of Paris, although none were native to that city. Born in Guadaloupe of a black woman and an unmarried white French aristocrat, Saint-George’s family came to Paris when he was ten. His first career was as a swordsman of the highest caliber, but he began to appear publicly as a violinist at the age of 25, and composed most of his opus from then until the early 1780s. The flamboyant introduction to L’autre jour à l’ombrage (“One Day in the Shade”) displays his love of the violin, and the melody follows in highly ornamented fashion.

Nicola Dalayrac was befriended by the Comte d’Artois and left his native Muret in 1781 against the wishes of his father. Although written for the comic opera Nina, Quand le bien-aimé reviendra (“When one’s Beloved Returns”) is more song than aria, and its mixed meter suggests earlier French dance forms.

Felice Blangini left Turin for Paris in 1781 to escape political unrest. C’est une misère que nos jeunes gens (“It’s a Misery — Our Young Men!”) highlights Blangini’s comedic flair. Both this song and Il est parti! (“He is Gone”), included in the next French group, demonstrate his penchant for moving a melody from major to minor and back again.

Anna Amalia von Sachsen-Weimar (1739-1807), niece of Frederick the Great, was married at sixteen. By the time she was eighteen, she had become the mother of two sons, a widow, and the regent of her duchy. A student of piano and 4 composition, she journeyed to Italy from 1778- 1780, returning to Weimar with a great appreciation for singing. She established museums and theaters, and her patronage encouraged Johann Wilhelm von Goethe and many other artists. In 1773, she wrote the singspiel Erwin und Elmire from which Auf dem Land und in der Stadt (“In the Country or the City”) is taken. Her compositions reflect the rhythmic and harmonic characteristics of the Baroque masters.

Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814) was influential as a literary critic, journalist, violinist, composer, and Kapellmeister to Frederick the Great. He was particularly active in developing liederspiel, which implies a song of dramatic or theatrical character. His extended setting of the ballad Johanna Sebus, chosen from a group of verses (1809) by Goethe, emphasizes the relationship between a natural disaster and the emotional turmoil of the heroine.

Corona Schröter (1751-1802) was a central figure in the artistic life of Weimar. She published a total of 31 songs in addition to singing, acting, painting, and teaching. In 1776, Goethe introduced her to Duchess Anna Amalia von Sachsen-Weimar, and Schröter soon became indispensable to the many plays, operas, singspielen, and dance performances undertaken by the Duchess’s “Court of the Muses.” Fur Männer uns zu plagen (“To be Plagued by Men”) was the second song in the singspiel Die Fischerin (1782), written with Goethe and performed on the banks of the river at Anna Amalia’s summer residence.

Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824) was a prodigy of Vienna court life, born to the imperial court secretary, and blind from childhood. She studied with, among others, Salieri and Righini, became an avid touring performer at the keyboard, and befriended Mozart, who wrote the Piano Concerto K. 456 for her. Morgenlied eines armen Mannes (“Morning Song of a Poor Man”), on a text of Johann Timotheus Hermes, explores the plight of the commoner. Paradies employs the poetry to create some of the most vivid text painting in songs of this era.

The last five entries Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1795) made into his thematic catalogue are framed by two Masonic cantatas. In July of 1791: “a little German cantata for voice and keyboard (K. 619)”; and the final entry on November 15: “a little Freemason cantata (K. 623).” In between come entries for Die Zauberflöte, La Clemenza di Tito, and the Clarinet Concerto. The Requiem was never entered into this log, yet it, too, supports the evidence of Mozart’s overriding concern with matters of humanity and the Brotherhood. During the early 1780’s, freemasonry took the Vienna elite by storm. By 1783, when Mozart began to attend meetings, princes, diplomats, artists, and merchants gathered to share fellowship, ritual, and socially progressive ideas. Mozart was initiated into Zur Wohltätigkeit (Beneficence Lodge) in December, 1784. Haydn made application to join the same year, and Mozart recruited his father in the following year. Suspicious of the Masonic Order, Emperor Joseph II decreed in December 5 1785 that the dozens of Lodges in Vienna must be reduced to three, making it easier to gather information about the Lodges and their participants through the secret police. Although the fever of popularity had left Vienna by 1791, Mozart and impresario Emanuel Schikaneder undertook an “act of allegiance” to their lodge: They created Die Zauberflöte, patterning the character of Sarastro on the ideal of the Master of the Lodge. Cantata K. 619: Die ihr des unermesslichen Weltalls (“The Unfathomable Creator of the Universe”) speaks with the same musical and poetic vocabulary as the singspiel. Three arioso passages — Andante triple time, Allegro duple, and Andante mixed meter — are framed by recitative sections and followed by a short Allegro coda. The affect is one of grandeur juxtaposed with simplicity, where form serves and supports idealism.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was an active composer and arranger of songs, especially during his ‘middle period,’ which is roughly framed by the 3rd and 8th Symphonies (1804 and 1812, respectively). He set Wonne der Wehmut (“Blissful Pain”) in 1810, the first in a group of three poems by Goethe. Beethoven’s unequal phrase lengths and motivic variation in the accompaniment sound very progressive in comparison to songs by most composers of this period.

Sophie Westenholz (1759-1838) married a musician serving at the court of Duke Ludwig of Schwerin, and earned her living as singer and pianist there. One of only 26 songs she composed, Morgenlied (“Morning Song”) of 1806 is important for its simple strophic form, rhapsodic piano introduction, demanding vocal tessitura, and warmly chromatic harmonies.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) represents the pinnacle of song composition for both the Classical and Romantic periods. He is unsurpassed in his ability to take a critical word or affect, and create in the accompaniment a musical figuration for its meaning. He developed the ballad form into a musical scena by composing in a style that was melodically compelling, even while changing key and tempo. Frühlingssehnsucht (“Spring Longing”) comes third in the group known as Schwanengesang — seven poems by Ludwig Rellstab that Schubert set just three months before he died.

Pauline Duchambge (1778-1858) was well known in 1830s Paris for her romances. This genre has also been called barcarolle, chansonette, ballade or nocturne, but whatever the name, this rather simple, strophic form featured sentimental and pastoral texts. Duchambge was born in Martinique to Creole aristocrats, studied in a convent in France, married at 18, and left her husband for the composer Daniel François Auber. She studied composition, performed as a singer and pianist, and published 300 songs in France and Germany. La jalouse (“The Jealous One”) is a verse by her dearest friend, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, a writer much admired by Balzac and Victor Hugo.

Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831) is represented by two songs. Both were identified as romances in their day, but Ballade is really a polonaise with words, and Se spiegar (‘If I Could Tell”) is written as a small dramatic aria. Szymanowska was a virtuosa pianist. She gave her first concerts in Warsaw and Paris in 1810, spent a decade in a marriage, toured Europe from 1823-1827, and settled in Saint Petersburg the following year as court pianist for the Tsarina.

Isabella Colbran (1785-1845) left Spain at the age of sixteen to pursue an operatic career in Italy. While serving at Teatro San Carlo, she found great success premiering the operas of Giacomo Rossini. She married Rossini in 1822 and retired from singing two years later. During her early years in Italy, she composed four collections of songs. Mi lagnerò tacendo (“I Shall Mourn in Silence”) sets the same Metastasio text as Righini, but Colbran’s rendition features a more florid vocal line and a relatively plain accompaniment.

Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) was born to a family of musicians in Catania. In 1819 he went to the conservatory in Naples, where he began to study the compositions of Mozart. Like Mozart, Bellini’s success as an opera composer was based on an excellent ear for language and musical characterization. Arietta (c. 1825) is one of the few romances he wrote, and it concludes this survey of song by celebrating the budding bel canto style dressed in Classical form.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:21

Recorded: January 12-15, 1999 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Patrice Michaels

© 1999 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 049