Store

These mostly world-premiere recordings project a musical panorama of the human experience from childhood to adulthood and beyond. Here are timeless truths told through enchanting poetry in settings that underscore the richness of their imagery.

The program opens with Five Songs for Children, with words by Edna St. Vincent Millay, Amy Lowell, Walter de la Mare, Christina Rossetti, and Emily Huntington Miller.

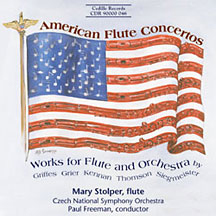

Light and whimsical, Sneezles is based on an A.A. Milne poem about the author’s favorite character, Christopher Robin. In Five Songs from “A Shropshire Lad,” Grier’s music underscores the urgency of the carpe diem message of A.E. Housman’s poetry. Two Songs from Emily Dickinson are, by turns, wistful and impressionist.

The album’s centerpiece, the Ravinia-comissioned, ten-song cycle Songs from Spoon River, comprises powerful portraits based on texts from Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology, in which fictional residents of a rural Illinois town reflect on their lives from beyond the grave.

This first-ever recording devoted exclusively to Grier’s music concludes with Reflections of a Peacemaker: five life-affirming verses by the late teen poet Mattie J.T. Stepanek (1990-2004), sung by the Chicago Children’s Choir conducted by Josephine Lee, with John Goodwin at the piano.

The stellar lineup of solo singers includes sopranos Michelle Areyzaga and Elizabeth Norman, tenor Scott Ramsay, and baritones Robert Sims, Alexander Tall, and Levi Hernandez, with pianists William Billingham and Welz Kauffman, President of the Ravinia Festival, taking turns at the keyboard.

Preview Excerpts

Five Songs for Children

Five Songs from A Shropshire Lad

Two Songs from Emily Dickinson

Songs from Spoon River

Reflections of a Peacemaker (2007)*

Poetry by Mattie J.T. Stepanek

Artists

1: Michelle Areyzaga, soprano

Welz Kauffman, piano

6: Michelle Areyzaga, soprano

Anne Bach, oboe

Tina Laughlin, percussion

William Billingham, piano

7: Robert Sims, baritone

William Billingham, piano

William Billingham, piano

12: Michelle Areyzaga, soprano

Welz Kauffman, piano

14: Elizabeth Norman, soprano

Michelle Areyzaga, soprano

Scott Ramsay, tenor

Alexander Tall, baritone

Levi Hernandez, baritone

Welz Kauffman, piano

William Billingham, piano

24: Chicago Children’s Choir

Josephine Lee, conductor

John Goodwin, piano

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Songs of Lita Grier

Notes by Ted Hatmaker

This recording of songs by Lita Grier brings us much to celebrate. It not only makes available a marvelous collection of vocal music, most of it for the first time; it also represents how an extraordinarily gifted composer was able to defy history and return to creating vibrant music after a 30-year hiatus. Such a return is virtually unprecedented, and the music community is fortunate to reap the benefits.

Having found her compositional voice early, Lita was awarded First Prize in the New York Philharmonic Young Composer’s Contest at age sixteen, during her first year at Juilliard. After completing her degree, she went on to earn a Masters degree in composition at UCLA, where she studied with Lukas Foss and Roy Harris. Along the way, her early songs, some of which are included here, and chamber music garnered awards and high praise. She seemed poised to settle in as one of the prominent composers of her generation. And then, suddenly, she walked away from it all.

Why would someone abandon the field of composition after such a promising start? To answer this question, one must return to the 1960s, when serialism, a compositional technique in which pitches (and other elements) are used in a specified order and manner to assure an atonal effect, reigned over the academic music establishment, and composers who did not conform were mocked as antiquated. In addition, female composers were not common, and many still felt composition should be an exclusively male domain.

Lita faced both of these prejudices. Rather than fight against the prevailing forces, she redirected her energies to other musical pursuits: artist management, public relations, writing, and finally, broadcast production, as Vice President and, after the death of her husband, President of Inter-Continental Media, producing outstanding musical series such as nationally-distributed radio broadcasts of the Vienna Philharmonic and Salzburg Festival. In the wake of this career shift she had left a number of high-quality pieces, and these took on a life of their own. Her flute sonata, violin sonata, songs, and other chamber works were distributed among musician friends and performed throughout this period, to overwhelmingly positive reviews. By the mid-1990s, the demand for new works became too great for her to ignore. Commissions began to stream in, and a career previously derailed by unfortunate circumstances was righted and continues rolling along to this day. In recent years, Lita has had entire concerts dedicated to her music, seen numerous recordings and countless performances of her works, and was named a Chicago Tribune “Chicagoan of the Year” in 2005.

This CD is the first commercially-available recording devoted exclusively to the music of Lita Grier. It is fitting that it features her songs because this genre spans from her earliest to her most recent compositions. Grier has set the words of illustrious English language poets with a regard for ultimate conveyance of their meaning. These are not songs in which the music competes against the word; rather they form a marriage that seeks to become more than the sum of its components. Employing her rich harmonic vocabulary, from glorious sonorities to pungent dissonances, Grier is able to give a contemporary voice to these poets of the past, and thus connect them with the modern listener. The result is music that projects how we feel inside when reading these poems.

The Five Songs for Children offer a unique opportunity to experience the integrity of Grier’s style. Although they seem cut from the same musical cloth, three of the songs were written early in her musical life, the other two 37 years later. A listener would be hard-pressed to determine which are which, because her early works were so mature and her later ones bear the same youthful zeal and harmonic imprint. (The first three songs were written in 1962, the last two in 1999.) The irregular meter and compound (long-short) rhythms of “Afternoon on a Hill” (Edna St. Vincent Millay), its rolling lines and shouts of glee, aptly suit the youthful narrator’s enthusiasm at an unchaperoned day on a hill overlooking town. In Amy Lowell’s “The Seashell,” voice and piano lines come to life to act out the stories told by the conch shell at the child’s ear. The repeated downward intervals that open the piano and voice parts sound familiar to all children-at-heart. Grier’s piano part serves here as a playfriend to the voice, playing first in counterpoint, then momentarily veering off on its own fantasy before rejoining the voice in its games. “Someone” (Walter de la Mare) depicts the annoyance of answering a knock at the door at night to find no one there, only the busy sounds of woodland creatures. Sharp staccatos represent both the knocking and the narrator’s perturbation. In the end, the voice part takes its leave after accepting it will never know who knocked. The piano, however, remains determined, and checks a couple more times before ending the song. The double quatrain of Christina Rossetti’s “Who Has Seen the Wind?” is handled masterfully by Grier. Gestures that begin one way in the first quatrain are inverted in the second. The effect is to alter the stress of the words: “Who has seen the wind?” versus “Who has seen the wind?” Tremolo “leaves” in the piano part help paint a haunting mood. Nature’s joyous song, complete with bird-chirp motive, bursts forth in “The Bluebird” (Emily Huntington Miller), which closes the set. This spirited waltz casts the bluebird as the harbinger of spring in a fervent song, with a vocal line spanning more than two octaves. The largely stepwise harmonic progression counterbalances the joyous leaps of the melody.

The setting of A.A. Milne’s “Sneezles,” from the collection Now We Are Six, is the lone work composed during Ms. Grier’s inactive period, which stretched from 1965 to 1995. She composed “Sneezles” in 1972, when she was reading from Milne’s collection to her young son, to whom the work is dedicated. Set for soprano, oboe, percussion, and piano, it features the exploits of Milne’s favorite character, Christopher Robin, as he occupies the adults in his life with a slight illness. The charm of Christopher Robin’s secret language of rhymes and the pomp of the various personages who attend him are skillfully exposed through the supple melody. The instruments supply appropriately descriptive commentary, but the percussion in particular adds a new dimension. The nearly-continuous shift among the battery of percussion instruments must make this work as delightful to watch as to hear.

Composed while still in her teens, the Five Songs from A Shropshire Lad is Grier’s earliest work on this recording. The simple, carpe diem message of A.E. Housman’s collection, from which these were taken, is neatly revealed in her music. The effect of love on a young man’s behavior is the topic of the first song. The skipping meter of the accompaniment mirrors the customary wanton behavior of the unattached narrator, not the well-heeled character of his former infatuated self. The poignant second song relates an eerie scenario: a young man walks with his lass beneath an oracle-like aspen, which predicts her death and, a year later, his own. The widely contrasting third and fourth songs are told in the second person from well-meaning, but clearly different counsels. To a jaunty, dance-like melody, the former prescribes a life of laughing, dancing, and drinking, since thinking too much will hasten death; in a more somber air, the latter recalls the biblical prescription to cut off any part of the body that causes you to sin, and to end it all “When your sickness is your soul.” The final song sets the best known poem of the collection, “When I was one and twenty.” Grier gives an edginess to the folk-like melody through polytonal references and metric shifts. Its spirited tempo slows only at the end to deliver the woeful moral.

While studying at UCLA, Lita Grier composed Two Songs from Emily Dickinson. It is hard to imagine a more powerful setting for Dickinson’s “I Cannot Live with You” than Grier’s heard here. Through logical argument, the narrator explains why love cannot be allowed between her and her beloved. The accompaniment lends a restrained forbearance to this wistful message of love’s impossibility. Despite this restraint, Grier lets the music reflect the emotional surge hidden behind the argument’s logic, as well as the disconsolation felt on the final word, “despair.” Poignant shifts of key and subtle integration of melodic motives give this song a gravity far exceeding that of the poem alone. “I Taste a Liquor Never Brewed,” Dickinson’s high-on-nature poem, is set to impressionistic colors and moto perpetuo arpeggiations and tremolos. It is a virtuosic song that taxes both vocalist and pianist.

Lita Grier’s longest and most ambitious work to date is the cycle Songs from Spoon River. Its ten vocal masterpieces are the product of three separate commissions from Ravinia Festival CEO Welz Kauffman for the festival’s Steans Institute for Young Artists. The first set, comprising songs one through four and the finale, was premiered in 2004 and is dedicated to Ravinia’s centennial year celebration. An overwhelmingly positive response led to a subsequent commission that yielded songs six through nine. Song five, “Anne Rutledge,” was added in 2009 in commemoration of the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth. The texts come from Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, a set of over two hundred poems that unveil a shockingly scandalous lifestyle in rural Illinois through fictional characters speaking from their graves. Grier’s brilliant array of expressions complements the characters’ diverse accounts, and offers vocal tours-de-force for high soprano, second soprano or mezzo-soprano, tenor, and baritone voices, accompanied by piano.

The opening song, “The Hill (Part I),” for tenor, introduces us to ten residents of the cemetery and their various fates, and sets the stage for the remaining songs. Its funeral dirge tempo and dark harmonies cast a touch of melodrama to the setting, and introduce the death motive (“all are sleeping on the hill”), which reappears in several songs. This song and its bookend counterpart, “The Hill (Part II),” are sung in the third person. All of the other characters speak for themselves. “Sarah Brown,” the second song, cautiously carves the poignant plight of a woman who loved another man as well as her husband. The singer’s final and highest note culminates her rationale: “There is no marriage in heaven, but there is love.” With the agitated “Zenas Witt,” the baritone portrays a student who suspects he is mortally ill, and has his suspicion confirmed when he reads his symptoms in an advertisement. A cough ensued, sending him to an early grave, where he “slept the sleep without dreams.” To a waltz, the matriarchal “Lucinda Matlock” outlines her happy, full life, and flippantly directs sharp criticism to mopey youths who don’t know how to enjoy themselves. The entire ensemble joins together for the first time in “Anne Rutledge,” a slow, dignified portrait of Abraham Lincoln’s early beloved. Grier brings back the dark harmonies from the opening song to capture Rutledge’s soliloquy. Even in death, “Petit the Poet” still obsesses over poetic meter, his thought processes apparently continuing by inertia. The accompaniment’s witty metric interplay with the tenor’s melody recedes only when he stops to reflect on how life passed him by. The ambitious novelist “Margaret Fuller Slack” finds herself undone by the “old problem” of sex, which drew her to matrimony: her eight children left her no time to write, and she died of lockjaw from an accident sustained while performing domestic chores. A rustic drone escorts the sprightly dance tune for the baritone’s joyous “Fiddler Jones,” a musician who was ill-equipped to thrive in his farming profession. A reprise of Lucinda Matlock’s waltz allows her granddaughter “Rita Matlock Gruenberg” to respond movingly to her ancestor’s criticism from a nearby grave. It was not lack of “strength, nor will, nor courage” that kept her from a happy, full life, but circumstances of fate. The ensemble reunites for the finale, “The Hill (Part II),” continuing the survey of various characters, as in part I, and concluding with an assessment of Fiddler Jones’s capricious life and comments over strains of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The colorful, the distracted, the maligned, the self-righteous — all are sleeping on the hill.

The life and writings of Mattie J.T. Stepanek (1990–2004) have been celebrated for many years now. Mattie understood more in his short life than most of us ever will, and his message of hope, peace, and courage inspired all who knew him, or knew of him. When commissioned by the Chicago Children’s Choir to write a work for its 50th anniversary in 2007, Lita chose to set five Stepanek poems for children’s choir and piano and call the set Reflections of a Peacemaker, the title of Mattie’s last published volume of poetry.

Mattie saw beauty and awe in the everyday; nowhere is this more apparent than in “As It Was in the Beginning.” Grier’s glistening harmonies spotlight key words such as “sunshine” and “glee,” while crescendos over each “–ing” of “thriving, reverberating, exhilarating” drive home how amazing a playground full of children can be. In “Eternal Role Call,” lush, rolling piano chords lead the children to delight in what each season brings to them. Even death contributes, for it gives them a chance to recognize those gifts that are part of life. The cycle of seasons is reflected in the end by a return to the opening harmony. “The Pirate Song” exemplifies Mattie’s “play” mode, which should be an important part of all our lives. Here the chorus members become fearsome pirates, with sound effects to punctuate their chantey. A more circumspect outlook is presented in “About Living (Part III).” Its message — live life to the fullest while you’re here — is captured movingly by the a cappella setting of this gracious anthem. The set culminates in “I AM,” an anaphoric feast in which the “I” is each one of us, and no matter what makes us the way we are, we are all miraculous just by being. This mature viewpoint from such a young man concludes the disc, neatly balancing the opening five children’s songs from celebrated adult poets.

Ted Hatmaker is a music theorist and composer who teaches at Northern Illinois University.

Album Details

Total Time: 67:45

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: September 8 and 9, October 13, 2008, and April 8, 2009, in Bennett-Gordon Hall at Ravinia, Highland Park, Illinois

© 2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 112