Store

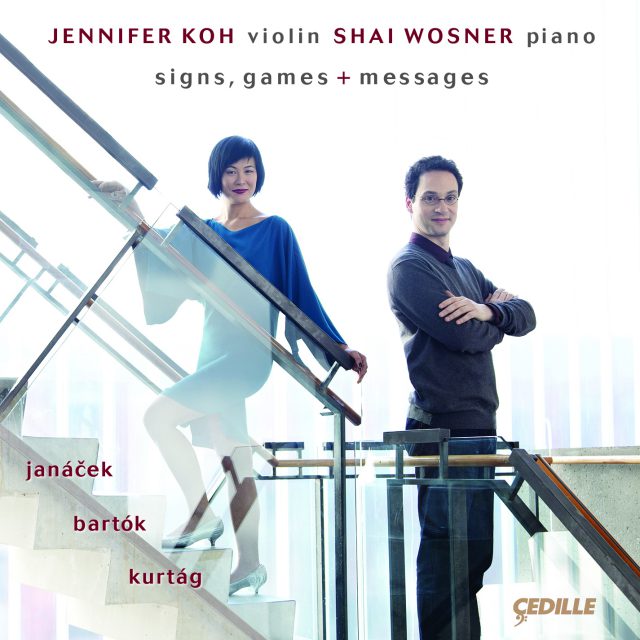

Grammy-nominated violinist Jennifer Koh and virtuoso pianist Shai Wosner play 20th-century works by three remarkable Central European composers who intertwine folkloric influences with their own unmistakable originality.

The album includes Leoš Janáček’s Moravian influenced Sonata for violin and piano, Béla Bartók’s impassioned Violin Sonata No. 1, and compelling miniatures by György Kurtág, including Tre Pezzi for violin and piano and selections from Signs, Games and Messages.

The Philadelphia Inquirer praised Koh’s “strikingly beautiful” playing in the Bartok sonata. Wosner brought a “diaphanous tone deeply sympathetic to the Debussy-like writing” to the Janáček.

Preview Excerpts

LEOŠ JANÁČEK (1854–1928)

Sonata for Violin and Piano JW VII/7

GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926)

Tre Pezzi for Violin and Piano, Op. 14e

BÉLA BARTÓK (1881–1945)

First Sonata for Violin and Piano, Sz. 75

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album Bookletsigns, games + messages: Janácek, Kurtág, and Bartók

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

While we know a lot about Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály’s research into Hungarian and Romanian folk music during the first decade of the 20th century, and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s parallel work in English folk music around the same time, music lovers tend to be less aware of the research Leoš Janácek undertook in the realm of Slavic folk music some twenty years earlier. These were his years of obscurity as an ambitious, dedicated, but virtually unknown composer earning his living as a music teacher and organist in the Moravian city of Brno. Native folksongs became the basis of his ideas about speech-melody; he heard parallels between traditional tunes and the rhythms and cadences of language. Critic Bernard Jacobson has noted “the curiously abrupt rhythmic style of much of his instrumental music,” linking it to the unpredictable and varied sounds of speech.

Another inspiration for Janácek was his ardent belief in the pan-Slavic idea: the cultural linkage of all nations and peoples with a Slavic heritage (he was especially interested in the culture of Russia). His patriotic heart rejoiced when an independent Czechoslovakia (now two nations, Slovakia and the Czech Republic) emerged after the First World War, free (temporarily, as it turned out) from the Austro-German domination that had lasted for centuries. His Violin Sonata, composed and re-composed between 1914 and 1921, is seen by his biographer, Mirka Zemanova, as a kind of reaction to that conflict.

The sonata’s occasional Russian flavor has been linked to Janácek’s 1920 opera Kát’a Kabanová, based on a Russian story, with which it shares some thematic ideas. It was another opera, Jenufa, that first gained Janácek national and international recognition after it was premiered in Prague in 1916. In the 1920s, Janácek enjoyed one operatic triumph after another and also composed his choral masterwork, the Glagolitic Mass (1927). His Violin Sonata was first performed in Prague in 1922.

Zemanova notes that many Janácek instrumental works originated well before the Jenufa success. “Their complicated history,” she writes,

testifies to Janácek’s stubborn quest to perfect other genres at a time when productions of his operas were hindered through the lack of understanding as well as ill luck. But by the time the composer more or less reluctantly sanctioned the publication of these works, his success on European operatic stages was assured, and his insecurities long forgotten. The dramatic intensity of the Sonata for Violin and Piano, in particular, was soon to win it audiences in many countries… [it is] a work of great power which rightly holds a special place in the violin repertoire.

The most common key signature in the sonata’s four movements is five flats, which can signify D-flat major or B-flat minor, but there’s no firm tonal center in the sense we’d encounter in the D-flat works of, say, Chopin or Tchaikovsky. Key centers and modes — major or minor — shift constantly as Janácek adds in chromatic tones and sharp dissonances. The highly dramatic opening movement marked Con moto (moving) opens with a mournful, improvisatory violin statement soon joined by powerful, fast-moving piano figurations. The broad melody of the movement’s main theme is contrasted with a striking motive that occurs and recurs in both instruments: an agitated figure of three falling 32nd notes. Themes, fragments of themes, and tiny motives are constantly juxtaposed and constantly shifting through continual tempo and dynamic changes.

The earliest music in the sonata is its second movement, subtitled Ballada, which may have originated as early as 1908. A lyrical E major theme for violin is supported by a piano part based on fast-moving 32nd notes and further characterized by complex chords. The tempo marking, con moto, could easily have the word “espressivo” added. The mood is quite different from that of the Sonata’s opening — sometimes almost dreamy. Once again the key center is constantly shifting as melodic ideas are stated and repeated in a rondo-like fashion. Toward the end, the violin takes one of these melodies and soars very high with it in an improvisatory style over the piano’s agitation; this subsides into a slower conclusion marked ppp, extremely soft.

So far the basic meter has been triple, 3/4 or 3/8 time. The Allegretto scherzo, in 2/4, starts out with a pounding folk-like theme in the piano part. Triple meter returns in the broader-paced, somewhat declamatory middle-section succeeded by a return of the opening folk theme and an abrupt ending.

Sonata finales tend to be lively and upbeat. Janácek’s begins adagio, although that pace and the time signature keep changing. The piano states the main theme in octaves, a sad melody that proceeds in half-steps, augmented fourths, and minor sixths. Over this the violin, playing with a mute and at first only on its lowest string (G), interjects intense, jabbing little triplet figures. Mournful melodic passages and mysterious interjections continue to be juxtaposed and exchanged between the instruments as the movement builds to a climax. The conclusion returns to the sound of the movement’s opening as the piece ends adagio and pianissimo.

The proliferation of musical styles and approaches in the 20th and 21st centuries has made it much harder than in the past to pigeonhole today’s composers. György Kurtág’s creativity, for example, would never fit into any kind of box. Whether it’s one of the miniatures heard on this recording, or a large-scale work like Stele, written for Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic, or the Concertante for violin, viola, and orchestra (which won the Grawemeyer Award in 2006), Kurtág creates a sound-world all his own. Born in Hungary in 1926, Kurtág (like Bartók) studied and later taught at Budapest’s Franz Liszt Academy. A brief sojourn in Paris shortly after the 1956 Hungarian uprising led to contact with composers Olivier Messiaen and Darius Milhaud and the plays of Samuel Beckett. After a long teaching career, Kurtág served as composer-in-residence for the Berlin Philharmonic from 1993 to 1995. He has lived in France since 1999. As a pianist in concert and on recordings, he has performed in partnership with his pianist wife, Marta, building programs around selections from his eight volumes of Játékok, or Games, originally for piano solo and piano duet. The sequence of Játékok began in 1973; the sequence of Signs, Games and Messages originated in 1961 and likewise became an ongoing project. The Tre Pezzi (Three Pieces) for violin and piano date from 1979.

Britain’s Tom Service, who writes for The Guardian and hosts music broadcasts on BBC Radio 3, wrote on one of his blogs that the Játékok symbolize

a compositional journey that has often involved reducing music to the level of the fragment, the moment, with individual pieces or movements lasting mere seconds, or a minute, perhaps two… Kurtág’s apparent obsession with this smallness of time-scale isn’t some kind of post-Webernian quest to split the musical atom or to find the structural essence of music. Far from a “reduction,” Kurtág’s fragments are about musical and, above all, expressive intensification: maximizing the effect and impact of every note, every gesture… Ever since the piece he thinks of as his Opus One, a string quartet written in 1959… Kurtág has composed a huge catalogue that resonates with the music of the past he loves most — Bach, Schubert, Schumann, Beethoven, Bartók, Webern. It also speaks with a fearless directness that bypasses musical tradition and becomes its own idiom.

Doina for solo piano from Játékok, Vol. 6 is marked parlando (similar to speech) con moto (with motion). This ruminative gem is all about the clash of minor seconds, frequently B-natural against B-flat. The doina is an improvised folk tune Bartók discovered in what is now Romania, but it has also been linked to the klezmer music of Eastern European Jewish communities and sources as far away as northern India. Perhaps it traveled along the Silk Road.

The Carenza Jig, for solo violin, from Signs, Games and Messages: intervals of a major fifth, played consecutively or as double-stops, pizzicato and arco, often following the tones of the violin’s open strings (G, D, A, and E). A jig is a lively dance known in many cultures. Marked “Brisk and Wild,” this one is notated on a single page and lasts less than 50 seconds.

Tre Pezzi for violin and piano, Op 14e: In the first of these three short pieces, we once again hear violin open-string fifths. This time, the violin part is in C major over a widely spaced piano part notated in five sharps — B major: an automatic clash. The second piece, Vivo, starts very softly, with ethereal high violin notes over leaping piano figures. It grows to fortissimo in the middle, subsiding to quadruple piano at the end. The slow third piece is the shortest. Subtitled Aus der Ferne (From Afar), it gives the violin a semichromatic scale pattern over long, sustained piano notes and is marked quadruple piano throughout.

Fundamentals No. 2 for piano and wordless voice from Játékok, Vol. 6 features vocal sounds, including one labeled “unpleasant,” over a few soft, isolated piano tones.

In Memoriam Blum Tamás for solo violin from Signs, Games and Messages is characterized by intricate intervals, sometimes major triads or major fifths, sometimes sevenths or augmented fourths. When the violinist plays the same note on two strings at once, the score says these unisons “should be markedly discordant, the lower string played nearly a quarter-tone lower.” The tempo marking is “calm and serene,” the mood markedly mournful.

Like the flowers of the field… for solo piano from Játékok, Vol. 5 contains the tempo marking legatissimo possibile, telling the pianist to play as smoothly and sustained as possible. In it, a melody characterized by its use of intervallic seconds sounds alternatively loudly and very, very softly.

Marked vivace, Postcard to Anna Keller for solo violin from Signs, Games and Messages is over almost before it begins. This bright and cheerful message is written almost entirely in double-stops, with two brashly dissonant chords delivering its concluding signature.

Musical humor in six measures: A Hungarian Lesson for Foreigners for piano and voice from Játékok, Vol. 6 contains a total of 10 strikes on the piano keyboard.

Fanfare to Judit Maros’ wedding for solo piano from Játékok, Vol. 5 is very festive to suit the occasion. With a dynamic ranging from one f (loud) to four fs by the end, and a tempo marked vivacissimo, the piece consists of an almost impossibly fast cascade of runs and percussive chords, except for two triple-soft measures nearly halfway in.

Les Adieux in Janáceks Manier for solo piano from Játékok, Vol. 6: The title is a reference to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 81a. Les Adieux translates to “Farewell” in English. This complex intervallic blend of consonant major sixths and clashing minor sevenths, to be played mostly in a soft dynamic with indications such as dolce (sweet) and quasi in sogno (like a dream), makes a poignant and enigmatic evocation.

In Nomine—all’ongherese for soloviolin from Signs, Games and Messages: The quietly passionate combination of rapid runs and tranquil sostenuto playing, to be played with great rhythmic freedom, creates a violinistic tour de force in miniature. Diatonic and chromatic measures, consonance and dissonance, succeed each other almost without warning. The term “In Nomine” derives from a medieval liturgical chant whose theme was later adopted for instrumental music. The title suggests a Hungarian melody treated in the same manner.< /p>

The impact of Béla Bartók on the history of modern concert music is almost impossible to overestimate. A pioneer of ethnomusicology and the creator of six groundbreaking string quartets, three brilliant piano concertos, numerous ballets and dance suites, and the beloved Concerto for Orchestra, Bartók was an influential teacher and celebrated pianist as well as one of the 20th century’s preeminent composers. This recording reminds us of his important relationships with several major violinists, including Yehudi Menuhin and Joseph Szigeti. Another, not so well remembered, was Stefi Geyer, the romantic inspiration for his long-suppressed First Violin Concerto. Yet another was his countrywoman Jelly D’Aranyi, the descendant of a prominent Hungarian musical family whose great uncle was violinist and composer Joseph Joachim, a close friend of Brahms. For D’Aranyi, Bartók composed two violin sonatas in the early 1920s, the first of which they premiered together in London in 1922.

In their personal reflection for this album, Jennifer Koh and Shai Wosner note the intricacy of folk music’s impact on the three highly innovative creators represented on this disc. It’s not a matter of direct quotation, but rather the effect of inward understanding. The folk music element in Bartók’s music stems from an intimate comprehension of his sources’ rhythms and melodies that he internalized and blended with his own artistic voice. It can be heard in the sonata, if not overtly defined. It’s part of the music’s soul.

Whole-tone and pentatonic scales are found in folk music as well as in the works of Debussy. They can be heard frequently in Bartók’s First Sonata, which is an ambitiously conceived expansion of tonality as we know it. Bartók identified the basic tonality of his work as C-sharp minor, and indeed, as is traditional for a classical sonata, the first and last movements are centered around this key (the middle movement is in F-sharp minor, which, according to sonata tradition, is a plausible key for the slow movement of a work in C-sharp). Structurally, too, the movements follow some sonata ideals (sonata form in the first movement, rondo in the last). However, Bartók’s harmonic language is multi-layered and highly complex, enriching his chords with carefully ordered dissonances and packing each movement with many themes in a way that lends the music an almost stream-of-consciousness-like spontaneity. This is especially apparent in the opening Allegro Appassionato. Both instruments enter with jarringly abrupt themes. Meter, tempo, and dynamics keep shifting as each instrument pursues its own virtuosic path. There are pounding octaves and huge jumps for the piano. The violin part features equally large jumps and brilliant runs over the instrument’s whole range. The storm passes, however, into a quiet and contemplative ending.

The Adagio central movement opens with a lengthy violin solo, based in part on astringent intervals including the augmented fourth, sometimes called the tritone, which spans three whole tones (such as C to F-sharp) and is characteristic in a great deal of Bartók’s music. The piano joins in with widely spaced chords. This meditative opening is soon succeeded by the movement’s midsection, where a drone pattern in the piano’s deep bass introduces fragmentary and increasingly agitated violin figurations. Great tension is resolved into a return of the first theme, elaborated and expanded.

Introduced by a dramatic piano flourish, the violin kicks off the finale with an energetic passage played initially on the instrument’s low G string, giving a hearty and earthy quality to this dance-like Allegro. The tempo marking, which translates as “lively,” seems an understatement for this virtuosic, perpetual motion sonic panorama. Hugely spaced chords in both instruments contrast with 16th note runs ranging from low bass to high treble. Fierce dissonances intrude throughout. The overwhelming impression is one of headlong ferocity, sometimes taking on the quality of a devil’s dance, with momentary sustained pauses permitting only a brief drawing of breath before the frenzy returns.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 76:15

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City, April 27–28 and October 14–17, 2012

Cover Design: Sue Cottrill

Cover Photography: Jürgen Frank

Inside Booklet and Inlay Card: Nancy Bieschke

CDR 90000 143