Store

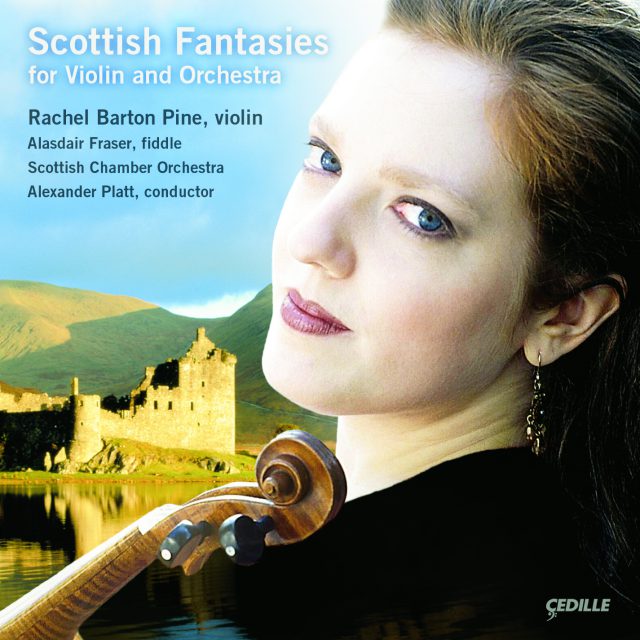

Rachel Barton Pine’s disc of Celtic flavored works is the first to present Bruch’s beloved Scottish Fantasy in an insightful and virtuosic interpretation that highlights its Scottish roots. The album also features Sarasate’s Airs Ecossais and two pieces by Scottish composers: Mackenzie’s Pibroch Suite and McEwen’s Scottish Rhapsody “Prince Charlie.” Ms. Pine’s own Medley of Scots Tunes, arranged and performed with famed Scottish fiddler Alasdair Fraser is also included. As a bonus, the package includes a video documentary on the making of Scottish Fantasies.

Preview Excerpts

MAX BRUCH (1838–1920)

Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46

PABLO DE SARASATE (1844–1908)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletScottish Fantasies

Notes by Rachel Barton Pine

In Scotland, the cross-fertilization between classical violin music and traditional fiddle tunes began in the 18th century, more than a hundred years before the pieces featured on this album were written.Musical Societies which presented classical concerts flourished throughout the country. Legendary fiddlers such as Robert Mackintosh, William McGibbon, Charles McLean, and James Oswald were respected also as classical performers and composers. The same violinists who performed in a Handel Oratorio or a Corelli Concerto Grosso one night might be playing for a dance the next evening.

Because fiddle players in Scotland had an unusually high rate of musical literacy, their folk music, unlike that in other countries, was often learned and transmitted in writing. As a result, hundreds of printed and manuscript collections were created between the 1740s and the end of the century. Within these collections, baroque sonatas mingle with simple tunes and their cello accompaniments. Some sonatas were Italian in style, often with Scottish embellishments. Others were Scottish tunes transformed into suites of baroque dance movements. Virtuoso variations on folk tunes were yet another genre, giving Scottish fiddlers an opportunity to demonstrate many of the innovative techniques being developed by classical violinists on the continent.

Reciprocally, continental composers such as Geminiani, Veracini, J.C. Bach, Haydn, Weber, Beethoven, Berlioz, Bruch, and Sarasate arranged Scots tunes or incorporated them into their compositions. Purcell and Brahms wrote imitation Scottish songs. Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 (“Scottish”) and Hebrides Overture were inspired by a visit to Scotland, although those works’ connection to Scottish folk music is tenuous at best.

The best known classical violin piece based on Scottish fiddle tunes comes from a German composer, Max Christian Friedrich Bruch (1838-1920). He wrote the Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46 in Berlin in 1879-80 at the request of the Spanish violin virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate, to whom the work is dedicated. Although Bruch began conducting in England in 1878, he did not make his first visit to Scotland (Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Edinburgh) until 1882, more than a year after the Scottish Fantasy‘s premiere.

Bruch and Sarasate met in 1871 while both were returning from Zurich. In 1877, Bruch conducted his Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, with Sarasate as soloist. The public’s response was the most enthusiastic Bruch had ever received. Enraptured with Sarasate’s playing and wishing to compose something for him, Bruch quickly wrote his Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Minor, Op. 44. The two musicians premiered it together in London in November of the same year.

In 1879, Bruch wrote to pianist Otto Goldschmidt, “Yesterday, when I thought vividly about Sarasate, the marvelous artistry of his playing re-emerged in me. I was lifted anew and I was able to write, in one night, almost half of the Scottish Fantasy that has been so long in my head.” Bruch asked Sarasate for a meeting to collaborate on the new piece. Then, feeling that the Spaniard was unresponsive, the easily offended Bruch turned to Joseph Joachim for advice. Joachim premiered the piece in Liverpool on February 22, 1881. According to Bruch, Joachim “annihilated it” by performing with insufficient technique and a lack of proper feeling. Two months later, Bruch reconciled with Sarasate.

Sarasate first performed the Scottish Fantasy on March 15, 1883, with the London Philharmonic in a memorial concert for Wagner. His interpretations of the piece were among his most successful performances. A few other violinists of the day, including American Maud Powell, incorporated the Scottish Fantasy into their touring repertoires. In the first half of the 20th century, however, the work all but disappeared. Then, in 1947, it was recorded for the first time. Jascha Heifetz’s brilliant interpretation single-handedly re-established the piece and renewed the public’s affection for it. Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy is now a fixture in the repertoire of most concert violinists.

The Scottish Fantasy‘s original title was Fantasie für Violine mit Orchester und Harfe unter freier Benutzung schottischer Volksmelodien (“Fantasy for Violin with Orchestra and Harp, freely using Scottish folk melodies”). The role of the harp, an instrument associated with Scotland’s earliest traditional music, is nearly as prominent as that of the violin soloist. The work’s dark and brooding Introduction was inspired by the writings of Sir Walter Scott describing “an old bard contemplating the ruins of a castle, and lamenting the glorious times of old.”

Each of the Scottish Fantasy‘s four movements is based on a different Scottish folk tune. Bruch found some of them in a copy of Scottish Musical Museum by James Johnson (Edinburgh 1787-1789) during a visit to the Munich Library in 1862.

The first movement, Adagio cantabile, comes from the popular 18th century tune, “Through the Wood Laddie,” possibly McGibbon’s version. The original tune has a typical baroque flavor, using the old pentatonic scale. Bruch transforms it into a lush, romantic melody by employing double stops and the key of E-flat major. This tune is often misidentified as “Auld Rob Morris,” one of the traditional tunes Bruch arranged for voice and piano in his Twelve Scottish Songs of 1863.

The second movement, Allegro, is based on “The Dusty Miller,” a lively, cheerful tune that first appeared in the early 1700s. The entrance of the solo violin over a bagpipe-like drone is marked Tanz (dance). “Through the Wood Laddie” is revisited in the transition to the third movement. The main theme of the Andante sostenuto, the emotional heart of the work, is derived from the 19th century song, “I’m A’ Doun for Lack O’ Johnnie.” Bruch’s beautiful voice-like treatment of the solo violin’s opening statement of the theme was no doubt informed by his skill and experience in writing for singers.

The main theme of the Finale is the unofficial Scottish national anthem, “Scots, Wha Hae,” Robert Burns’ tribute to the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn. This ancient tune has taken on many different titles and sets of lyrics, dating at least to the 15th century. Interestingly, Bruch sets the same tune in his Scottish Songs, using an earlier set of lyrics and the accompanying title, “Hei Tuti Teti.” While the tunes used in the Scottish Fantasy are not identified, the extroverted character of the triple stops in the movement’s opening and the marking Allegro guerriero (fast and war-like) make a solid argument in favor of “Scots, Wha Hae.” Variations on this tune are interspersed with a contrasting lyrical melody. After one last appearance of a phrase from “Through the Wood Laddie,” the Scottish Fantasy concludes triumphantly.

A stubborn anti-modernist, Bruch wrote of the “feeling, power, originality, and beauty of folksong being a salvation in unmelodic times.” Although he also drew from Swedish, Russian, Welsh, and Hebrew folk melodies for many compositions, he was particularly fond of Scotland’s music. He said that the Scots tunes “pulled me into their magical circle” and that they were more beautiful and original than folk tunes from Germany. He once wrote, “Whoever bases a composition on folk melodies, his work can never become old and wizened.” Bruch claimed to know over 400 Scotch songs.

The following recollections from Mackenzie’s autobiography, A Musician’s Narrative, published in 1927, are illustrative.

With him [Max Bruch] I conversed much and was sharply questioned about the state of music in London . . . When he assured me of his intense interest in Scottish folksong, saying “Es hat mich eigentlich zum komponieren veranlasst” (It really incited me to compose), I hardly realized how much truth the statement contained until I heard the once popular prelude to his own Lorelei. A prominent subject in that piece consists of four bars of the second part of “Lochaber no more.” As a wide distance separates the Rhine and the Highland moor, the connexion seems a remote one.

And the opening bars of the often sung Ave Maria in Das Feuerkreuz are clearly recognizable as our old song, “Will ye gang to the ewebuchts, Marion.” . . .

Apart from his great ability as a conductor, the impression created by Bruch’s personality upon me was that of a highly-cultured, musically-gifted man, somewhat cynical of speech and brusque of manner.

It is commonly believed that the greatest work for violin and orchestra based on Scottish folk melodies was written by Bruch, a non-Scot. However, Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie‘s (1847-1935) Pibroch Suite might easily be considered its equal. And yet, this masterpiece by an important composer is virtually unknown – in Scotland and in the rest of the world. Perhaps its neglect can be attributed to the Scots’ notorious dismissal of their own composers, especially when comparing them to England’s.

Nevertheless, Mackenzie is recognized as one of the greatest British composers of his time. His extensive output includes many operas, oratorios, orchestral works, chamber music, and instrumental compositions, including many for violin. Franz Liszt, Hans von Bülow, and Sir Edward Elgar were among his many fans and supporters. After playing the violin at the premiere of one of Mackenzie’s cantatas, Elgar declared that meeting Mackenzie was the event of his musical life.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Mackenzie started out as a violinist and Scots fiddler. Although he played in the violin sections of local orchestras, he did not want to remain a professional violinist. The limited music scene in Scotland led to his studying in Germany and traveling to London to extend his career. He began composing while in his early teens and was composing fulltime by age 32.

“I realized that, following in my parent’s footsteps, a careful study of our national music would be the shortest, indeed the only way to win any degree of popularity at the start,” Mackenzie states in his autobiography. “On my own inclinations no tax was needed, for its touching verse and melody always had a fascinating hold upon me, and the results of the preparation soon justified the resolve.” Thus, like his three Scottish Rhapsodies for Orchestra and his Scottish Concerto for Piano (written for Paderewski), many of Mackenzie’s compositions have a programmatic or nationalistic character.

He compiled and arranged Scots tunes for published collections, and even composed original tunes. “A tune of my own, evidently so racy of the soil as to have been accepted as a genuine antique of long forgotten parentage, was innocently reproduced as such, and for some years I have enjoyed the pleasure of hearing myself played and whistled ‘incog.'”

In 1888, Mackenzie became Principal of the Royal Academy of Music. During his 36-year tenure, he co-founded the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, and was active as a conductor, teacher, and lecturer.

Mackenzie began his Violin Concerto in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 32, in 1884. It was to be performed at the 1885 Birmingham Festival with Joachim as soloist. Because the work was written with Joachim in mind, its character is decidedly Germanic. At the last minute, Joachim backed out, possibly because of his ongoing divorce proceedings. Sarasate agreed to take on the challenge, even though he and Mackenzie had only met in passing after an 1881 concert in London.

Sarasate enjoyed Mackenzie’s concerto and performed it often. After successful concerts in Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1885, he asked Mackenzie to write a piece for violin and orchestra that had the flavor of the composer’s native country. The Pibroch Suite, Op. 42 was dedicated to Sarasate, who premiered it at the Leeds Festival in 1889 under the composer’s baton. Sarasate subsequently performed the Pibroch Suite on tour throughout Europe, America, and Mexico. Mackenzie also dedicated his Highland Ballad, Op. 47, No. 1, to Sarasate in 1893.

In his autobiography, Mackenzie affectionately describes his “dear friend” Sarasate and the first performance of the Pibroch Suite:

To know Sarasate was to love a simple-minded, unaffectedly modest and generous artist. There cannot be many with a greater claim to speak of his gifts and character, for I enjoyed an intimacy which revealed the estimable qualities of the musician and man.

Easily pleased as a child, in spite of all temptations quite free from vanity, living for his violin alone, he disliked “Society,” and his joy was to entertain a circle of congenial friends and compatriots; the more the merrier.

A very much more cultured musician than some of those who dubbed him “Prima Donna” were capable of judging, his favourite recreation was chamber music and quartet playing; but, aware of limitations and his own métier, these pleasures were mostly reserved for private enjoyment. In my opinion, Sarasate left a deeper mark upon violin playing than any other performer of his day.

The more laboured style of the North German school at times provoked gentle ridicule from one whose outstanding qualities were an entire absence of effort, a fascinating natural grace, and unfailing certitude of intonation. . . . An opportunity of realizing the phenomenal ease with which all this was achieved was mine when, at his invitation, we enjoyed a fortnight’s companionship at Frankfort, where he introduced my Pibroch to Germany under the composer’s direction. Occupying a couple of bedrooms leading to a circular sitting-room, we were so constantly together that there could be no question of practice without my knowledge. During the two weeks his violin-case was only opened twice: once to put on a new E string before leaving for rehearsal, and again to assure himself that all was well on the evening of the performance. Five minutes sufficed on each occasion; serious study and practice were confined to the leisure of his summer holidays at San Sebastian. A method not to be recommended for adoption by less agile-fingered instrumentalists.

Mackenzie had related this story previously as part of his eloquent tribute to his recently deceased friend in The Musical Times in November, 1908. Also included in that article is a quote from a letter Sarasate wrote a few days before the Pibroch Suite‘s premiere.

I was pleased to show myself on this occasion a true-blooded Scot – with the exception of costume – and to prove that your national music is some of the most beautiful and poetic that exists in the world: you know that I’m a great fan.

The first movement of the Pibroch Suite, Rhapsody, has a free-form style. While not quite a full-fledged movement in its own right, it is more substantive than just an extended introduction. After two cadenza-like statements from the soloist, the main theme first appears, accompanied by a harp. This Celtic-flavored melody of Mackenzie’s own creation could almost be a traditional fiddle tune until it flows into an obviously 19th century world of harmony. The structure and orchestral colors of this movement create a world of sound very similar to the opening of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy, but Mackenzie uses many more “gaelicisms,” such as Scotch snaps and turns, in his original material.

The second movement, Caprice, is an introduction, theme, and variations on the traditional tune, “There’s Three Good Fellows Down in Yon Glen.” This tune appeared in printed collections from the 1740s by McGibbon, Oswald, and others. Melodic interludes are inserted after variation 6 and the final variation 9. The movement ends with an unaccompanied cadenza that leads into the last movement.

At first glance, it would appear that the Caprice accounts for the work’s title, Pibroch. The repertoire of the Great Highland bagpipe is divided into two categories: ceòl beag (“small music”), which includes lighter airs and dance music, and ceòl mór (“large music”), also called pìobaireachd (“piping”). Pìobaireachds are a ceremonial form often written to celebrate or lament events such as a battle or the death of a hero. After beginning with a painstakingly slow statement of the theme or ùrlar (“ground”), an extended set of variations build upon one another, not unlike today’s minimalist music. The work ends with a repetition of the ùrlar, which may also appear as a reference point once or twice throughout the piece. Pìobaireachd is an acquired taste, and listeners and performers who truly appreciate it describe the experience as being almost spiritual.

There are some key differences between Mackenzie’s Caprice and a real pìobaireachd. “There’s Three Good Fellows…” is a charming tune, but clearly in the ceòl beag category. Each variation has its own separate character. Together they form a typical 19th century showcase of a virtuoso’s catalogue of pyrotechnical tricks (false harmonics, arpeggios, playing on the G string alone, fingered octaves, left-hand pizzicato, etc.). The slower melodic interludes are reminiscent of appearances of the ùrlar, but the melody is entirely different from that of the variations.

In his autobiography, Mackenzie writes, “Years ago a Highland piper at Blair Athol enlightened my ignorance by describing a pibroch as ‘Juist a sumphony, Surr.’ Not far wrong.” It is doubtful that Mackenzie titled his Pibroch Suite in error. Rather, the title was probably in homage to the bagpipe’s “classical” music, not a description of his own composition’s architecture.

The short, flashy last movement, Dance, incorporates two traditional tunes. The major-key “Leslie’s Lilt” is from the Skene manuscript (c.1625), which Mackenzie knew through its publication in Dauney’s Ancient Scottish Melodies. The contrasting minor-key tune, “The Humours of [the] Glen,” appeared in many notable 18th century collections such as the Flores Musicæ and fiddler Neil Gow’s Complete Repository. The two brief moments of slow melody towards the end of the movement are taken from the B section of this tune.

Pablo Martín Melitón de Sarasate y Navascuéz (1844-1908) was a Spanish violin virtuoso and composer trained at the Paris Conservatoire. One of the greatest soloists of his era, he was renowned for his facile technique, pure tone, and impeccable phrasing. He inclined towards the lighter virtuoso repertoire. This leaning is also reflected in his own compositions, which include many Spanish dances, opera fantasies, and early pieces in the French style. His Airs écossais, Op. 34 could be grouped with his more famous foray into the arranging of fiddle tunes, Ziguenerweisen, Op. 20 (Gypsy Airs).

Many composers were inspired by Sarasate’s playing and dedicated works to him. Among these were Bruch, Mackenzie, Saint-Saëns (Concertos Nos. 1 and 3; Introduction et Rondo capriccioso), Lalo (Concerto in F Minor and Symphonie espagnole), Joachim (Variations for Violin and Orchestra), Wieniawski (Concerto No. 2), and Dvorák (Mazurek). Scott Skinner, the greatest Scottish fiddler of the time, dedicated his virtuoso piece for violin and piano entitled Will O’ the Wisp to “the eminent violinist.” It is not known whether Sarasate and Skinner ever met.

Sarasate spent a significant amount of his career touring in Great Britain, where he was very popular and successful. In December 1893, he performed in Glasgow and at Balmoral Castle at the invitation of Queen Victoria. Upon returning to London, he starting writing Airs écossais, and continued to work on it in Paris during Christmas. For the orchestration, he consulted with Mackenzie. The work’s premiere in London’s St. James Hall on May 28, 1894, generated one of the most enthusiastic responses Sarasate had ever received. He dedicated Airs écossais to the great Belgian violinist and composer, Eugène Ysaÿe.

Unlike the more serious Scottish Fantasy and Pibroch Suite, Airs écossais is an unapologetic virtuoso showpiece. The orchestration displays great skill and taste, but unlike Bruch and Mackenzie, Sarasate relegates the orchestra to a purely accompanying role.

The piece is a medley of six traditional tunes. The first, a march, remains unidentified despite efforts to discover its source. (If you are able to “name that tune,” please let me know.) Next, Sarasate uses “Bog of Gight,” also known as “Lady Augusta Murray’s Strathspey.” In this section, he stretches virtuoso pyrotechnics to their utmost. A quick run through the B section of the reel “The Mason’s Apron” is followed by a brief, unaccompanied cadenza. The next slow, minor-key air is “(Oh) Open the Door, Lord Gregory.” The final two tunes are jigs: “Johnny McGill” or “Come Under My Plaidie” (also known by many other names) and “The New Water Kettle.” This last tune appears only in Gow’s Complete Repository among the 18th century collections. The Repository‘s inclusion of two of the other tunes in the same order as they appear in Sarasate’s medley suggests that Gow must have been one of Sarasate’s sources. Sarasate’s wickedly difficult pyrotechnics continue to the end.

Sarasate also wrote a version of Airs écossais for violin and piano. This is the first recording of his version for violin and orchestra.

Sir John Blackwood McEwen (1868-1948), who succeeded Mackenzie as Principal of the Royal Academy of Music, is considered one of the finest Scottish composers of the 20th century. In addition to orchestral works, nineteen string quartets, seven sonatas for violin and piano, and many works for solo piano, he also authored several books on harmony, aesthetics, and performance. His organic style melds influences of Scottish folk music, late romanticism, and impressionism. Lacking opportunities to have his larger works performed, he devoted his later life to writing chamber music. A co-founder of the Society of British Composers, he left his estate to Glasgow University to fund the commissioning and promotion of Scottish chamber music.

McEwen’s Prince Charlie Rhapsody for Violin and Piano was written in 1915 and published in 1924. When McEwen orchestrated the work in 1941, he added a lengthy cadenza. The orchestral score exists only in manuscript and without any orchestra parts. A very private man, McEwen wrote very little about his music or his thoughts. Therefore, one can only guess why he chose to orchestrate this piece without the motivation of a commission or an opportunity to present it in concert. The orchestration is appealing and imaginative, but it is likely that McEwen would have made some practical alterations had he heard the piece played. This recording marks the first performance of the 1941 version.

The Rhapsody takes its name from Bonnie Prince Charlie (Charles Edward Stuart), who led a Scottish Highland army in the doomed rebellion of 1745. The subject of numerous traditional tunes, Prince Charlie remains a heroic and romantic figure to present-day Scots. McEwen’s work uses three of these tunes: “Charlie is My Darling,” “Wae’s me for Prince Charlie” (or “Charles Lilt,” “The Gypsy Laddie,” “Johnnie Faa,” etc.), and “Hey Johnny Cope.” All appear in various 18th century collections; the second tune is also included in the earlier Skene manuscript. Sir John Cope, the subject of the last famous satirical song, was among the first to flee when his forces were overpowered by the Jacobites in the battle of Prestonpans.

The Prince Charlie Rhapsody opens with an extended introduction, with the solo violin utilizing the old Scottish pentatonic scale over a drone in the orchestra. Shortened versions of this introduction return between each tune and at the very end of the piece.

The violin and fiddle parts of the Medley of Scots Tunes were arranged for this recording in 2004 by Alasdair Fraser and Rachel Barton Pine; the orchestration was composed by Rachel Barton Pine. The medley begins with a slow air, “Lament of Flora MacDonald.” Flora MacDonald was imprisoned in the Tower of London after smuggling Bonnie Prince Charlie to safety on the Isle of Skye, dressed as a woman. This beautiful song is played first by Alasdair, then by Rachel with Alasdair playing descant, and then by a woodwind quartet. The bassoon’s bass line is taken from the cello accompaniment by Neil Gow. The next tune is “The Waukin of the Fauld,” a strathspey in which the melody is passed among the soloists and various instruments of the orchestra. A minor-key reel, “Miss Lyall or Mrs. Grant of Laggan,” gives each soloist a brief moment of improvisation over an orchestral vamp. It serves as a bridge into the final major-key reel, “Timour the Tartar.”

Album Details

Total Time: 81:30

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineers: Bill Maylone, Philip Hobbs

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond, Pete Goldlust

Cover Photo: Kilchurn Castle and surrounding hills beside Loch Awe © Stone

Photo of Rachel Barton Pine: © J. Henry Fair

Recorded: May 20-22, 2004, Usher Hall, Edinburgh, Scotland

Violin: “ex-Soldat” Guarneri del Gesu, Cremona, 1742

Luthier (violin technician): Whitney Osterud

© 2005 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 083