Store

Store

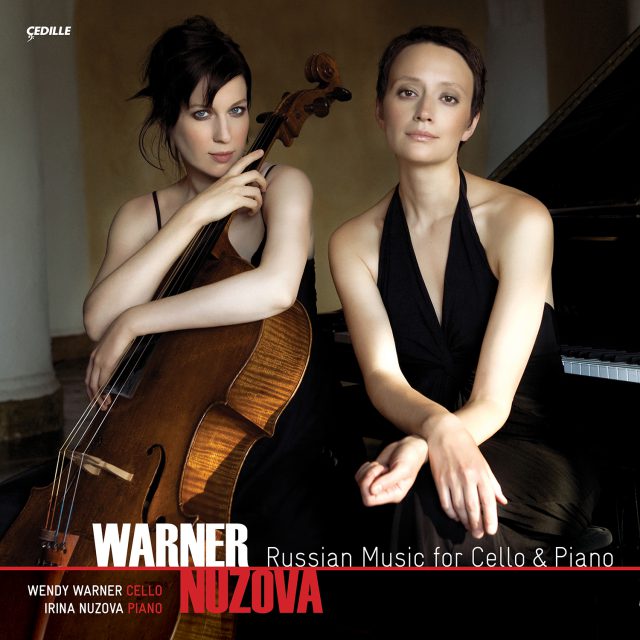

Russian Music for Cello & Piano

The Warner Nuzova duo — cellist Wendy Warner and pianist Irina Nuzova — makes its recording debut with five late-Romantic Russian works on an album dedicated to the memory of one of Warner’s mentors, the illustrious Russian cellist, composer, and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich (1927–2007). Fittingly, two of the pieces were originally written for Rostropovich: Nikolai Miaskovsky’s rarely heard Sonata No. 2 in A Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 81; and Alfred Schnittke’s Baroque-inspired Musica nostalgica, for violoncello and piano. This is the first American recording of Miaskovsky’s mellifluous Sonata No. 2, a work that’s rarely performed outside of Russia. It will be a discovery for most listeners. Alexander Scriabin’s Etude Op. 8, No. 11, is a beautiful encore piece brimming with chromatic harmonies; Sergei Prokofiev’s Adagio from Ten Pieces from Cinderella, Op. 97b, is based on a duet from his ballet; and Sergei Rachmaninov’s Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 19, is a riveting four-movement work from the same period as his Second Piano Concerto.

Preview Excerpts

NIKOLAI MIASKOVSKY (1881–1950)

Sonata No. 2 in A minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 81

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872–1915)

Transcription by Gregor Piatigorsky

ALFRED SCHNITTKE (1934–1998)

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 - 1953)

SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873 - 1943)

Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 19

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletRussian Music for Cello and Piano

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The spirits of three great Russian cellists permeate this CD of music from the late-Romantic and modern eras. Two of their names are familiar: Gregor Piatigorsky and Mstislav Rostropovich, among the greatest instrumentalists of the 20th century. The third is Anatoly Brandukov (1856–1930), a graduate of the Moscow Conservatory who later taught there. He had an international career as a soloist, chamber musician, and conductor, with particular success in Paris. His onetime theory teacher, Tchaikovsky, dedicated his [date] “Pezzo Capriccioso” to Brandukov. In 1901, the young Sergei Rachmaninoff dedicated to the cellist one of his few pieces of chamber music, the Sonata for Cello and Piano in G Minor. Brandukov and Rachmaninoff premiered the work in Moscow in December 1901, not long after the premiere of one of Rachmaninoff’s most enduring works, the Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor.

Brandukov’s listing in the current edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians (an evaluation by cellist-musicologist Lev Ginzburg) cites his “stylish interpretations, refined temperament, and beautiful, expressive tone.” The sonata gives the cellist ample opportunity for expressive playing through page after page of glorious melody. Yet this work also allows the pianist to shine and even frequently dominate the proceedings, reminding us that Rachmaninoff was himself a keyboard virtuoso.

The work’s short, pensive slow introduction presents a characteristic motive for the entire first movement: a rising semitone or half-step (e.g., B Natural to Middle C) heard right away in both instruments. These opening measures are in 3/4 time. For the main Allegro Moderato we shift to 4/4 meter and hear another characteristic cell in the piano part — a rhythmic one this time — two emphatic eighth notes followed by a quarter: ta-ta-TUM. The first theme, ruminative and expansive, in G Minor, is given to the cello with the indication “espressivo e tranquillo.” The second theme, in D Major, is heard in the piano first and heralded by the rhythmic cell. The exposition repeat is not taken in this performance; it goes directly to the development section, which focuses a good deal on the rhythmic cell and the rising semitone, and on a rapid 16th-note passage for the piano. The cello has pizzicato (plucked) as well as arco (bowed) passages while triplets in the pianist’s right hand set up two-against-three rhythmic patterns. To announce the approach of the recapitulation, the piano has what can only be called a cadenza, even though that kind of virtuoso solo passage is more associated with concertos than sonatas. The cello re-enters with broad leaps over piano chords to lead to the recapitulation, with the second theme returning in G Major in sonata-form tradition. The piano’s 16th notes coming out of the development introduce the energetic coda.

The Allegro Scherzando second movement begins and ends in C Minor. Its opening passages require the cellist to alternate quickly between pizzicato and arco over broken-octave patterns in the piano, played pianissimo at first and building up to fortissimo chords. The cello introduces a lyrical second theme in E-Flat Major. The “trio” midsection, very lyrical in both parts, modulates to A-Flat Major before the hushed C Minor returns for an almost note-for-note recapitulation of the opening.

Like the Scherzando, the Andante movement is ternary (A-B-A) in form. The piano opens with a simple E-Flat Major tune that’s picked up and expanded by the cello. The midsection returns to the work’s home key of G Minor. Although the Andante’s time signature is 4/4, the pace is varied by numerous triplet passages. G Major is the principal key of the fast-paced and emphatic finale. The triplet-laced first theme is dramatically propulsive in both parts; the second theme, marked “espressivo” for the cello, is a straightforward tune that firmly outlines the contours of a D Major scale. The development portion is dominated by triplet patterns and heavy chords for the piano. The recapitulation returns both themes in G Major. A sudden pause is heralded by a very low G in the bass of the piano, with broken chords above it and a soft cello melody that briefly brings back the two eighth notes and one quarter rhythmic cell and rising semitone of the first movement before the piece ends with a vigorous coda marked Vivace.

Few music-lovers will need to be introduced to the extraordinary life and career of Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007): cellist, pianist, conductor, composer, political dissident, and freedom-fighter. Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Britten were among the 20th-century musical giants who composed cello music that Rostropovich introduced to audiences worldwide. Less well-known than these is Nikolai Miaskovsky (1881-1950), who combined the careers of composer, critic, and teacher. His early education combined military training with musical studies; he served as an officer in the Russian Imperial Army during World War I and later was part of the early Soviet military establishment. But his longest tenure of any kind was on the composition faculty of the Moscow Conservatory, from 1921 until his death.

Miaskovsky is best remembered for having composed 27 symphonies, few of which are currently performed (several appeared in the repertory of the Chicago Symphony under Frederick Stock in the 1930s and 40s, however). Miaskovsky’s other works include concertos, band music, string quartets, piano scores, and a great quantity of songs. One of his last works, the Cello Sonata No. 2 in A Minor, full of song-like melodies, was written in 1948–49 and dedicated to Rostropovich.

The sonata’s style is very much in the lyrical late-Romantic vein in which Miaskovsky was comfortable and prolific all his life; it takes no note of the dissonance and atonality that had come to dominate classical music in the mid-20th century. Like pretty much everything by Miaskovsky, it’s seldom played nowadays. Although it can be found on a number of recordings, it’s likely to be a discovery for most listeners: a discovery combining lyricism, expressiveness, and grace. The opening Allegro Moderato movement is based on the usual structures of sonata form, but there are no clear divisions between sections and themes; the music feels continuous. The rippling outlines of A Minor and C Major triads in the piano part support a cello theme that’s reiterated in a higher register. A secondary theme in C Major moves in faster notes, mostly eighths instead of quarters, but the rippling effect continues. The development gives the first theme, transposed, to the piano, while the cello explores its full range from lowest to highest. A modulation to F-Sharp Minor punctuates the recapitulation, the second theme is briefly re-stated in A, and the coda is based mainly on the opening theme.

The 4/4 meter of the first movement is contrasted by the 6/8 triple-meter of the Andante Cantabile movement, whose first cello theme in F Major is a songful waltz melody. New material is introduced in F Minor and the movement proceeds through several key changes while its mood shifts from serene to rhapsodic as its harmonies become more chromatic. A concluding passage gives the cello a long descending scale over piano octaves. At the opening of the finale, Allegro con Spirito, the cello is asked to play spiccato: bouncing the bow across the strings instead of drawing it smoothly. This accentuates each note of the scurrying main theme, in A Minor, supported by chords and octaves in the piano accented off the beat. This movement is a Rondo, with the insistent main theme returning several times, contrasted with more relaxed sections, though the pace and forward propulsion never really slacken. There are stronger dynamic contrasts here than in the earlier movements, reinforcing the vigor of the themes and providing a sequence of unexpected surprises. At the very end, fortissimo decreases to piano, but the music does not just die away: the piece ends with a pair of triumphant fortissimo chords.

Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998) studied music in both Vienna and Moscow. He lived most of his life in the Soviet Union, and clashed occasionally with the system’s rigid artistic ideas. His last years he spent teaching, writing, and composing in the German city of Hamburg. His large work-list includes symphonies, concertos, chamber music, operas, choral works, and numerous film scores. Influences that have been discerned in his works, or that he himself cited, include Russian romanticism, the Austro-German symphonic tradition, Shostakovich, serialism, Baroque music, sacred music from the Middle Ages onward, jazz, and folk music. His symphonies can seem to channel Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Bruckner, and Berg, both quoting and distorting these sources. The result is usually termed “polystylistic.” What stylistic analysis can leave out is Schnittke’s sense of humor, which emerges in pieces that mock but also pay loving homage to music from the past. One such piece is “Musica Nostalgica,” written for Mstislav Rostropovich in 1992. Both composer and soloist must have smiled over and greatly enjoyed this simple Minuet, a wry little encore whose harmonies are almost aggressively diatonic. Perhaps its only departure from the 18th-century Minuet tradition comes through being mostly in a minor key (A Minor). After the simple opening melody exchanged between the players, there’s a short cello solo serving as midsection, then a varied repeat of the opening. Haydn would have loved it.

The all-too-brief, 43-year life of Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915) witnessed his transformation from a post-Chopin keyboard Romantic a post-Wagnerian musical philosopher espousing grand gestures and large orchestras. In his final years his focus shifted again, toward futuristic experimentation in the realms of polytonality and atonality. One wonders what innovations might have emerged from a longer lifespan.

Scriabin was a genius both on the small scale (e.g., his shorter piano works) and on the larger canvases represented by his full-length piano sonatas and works for orchestra. The Op. 8 Etudes of 1894, a set of 12 miniatures obviously modeled on Chopin’s two sets of similar pieces, reveal further influences from the virtuoso tradition of Liszt, Scriabin’s own taste for chromatic harmonies, and an air of moodiness often identified as a specifically Russian form of melancholy. The folk-like themes of the Op. 8, No. 11 Etude in B-Flat Minor, mellow and lyrical, must have felt especially apt for transcription to legendary cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, who created this lovely encore piece. Labeled Andante Cantabile and sticking mostly to the minor mode, it begins and ends very softly, with rich piano chords and passage-work supporting the cello’s song.

Serge Prokofiev’s ballet Cinderella comes from the years of World War II, when he also worked on the opera War and Peace: two 20th-century masterworks inspired by literary genres of the Romantic age — the fairy tale and the Russian novel. The ballet was unveiled at the Bolshoi Theater in 1945. Prokofiev extracted a set of piano pieces, Op. 97, from the full score and transcribed one of them for cello and piano, Op. 97b. This is the Adagio from Act 2, a pas de deux (duet) for Cinderella and the Prince, who have just discovered each other at the ball. The pace is that of a waltz, beginning almost hesitantly and gradually becoming more passionate.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Russian Recital

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Two works on this CD may be thought of almost as surprises, since they’re much better known in their symphonic incarnations. Sergei Prokofiev completed his Romeo and Juliet ballet in 1935, but neither the Kirov Ballet in then Leningrad or Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet was willing or able to mount it at that time. To make use of the music and keep the project in the public eye, the composer constructed two orchestral suites, which remain among his most frequently played scores, and a somewhat lesser-known ten-piece piano suite. (The full ballet was premiered in the Czech city of Brno in 1938 and finally made it to the Kirov stage in 1940.)

As orchestrated by Maurice Ravel, Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is in the repertory of virtually every orchestra in the world and has been recorded, often multiple times, by at least half of them. The undeniable vigor and brilliance of Ravel’s version has tended to obscure Mussorgsky’s original conception of the work as a pictorial suite for piano. It’s a highly original work in its strong linkages between the sounds of the keyboard and the vivid images that inspired them.

Prokofiev’s Sixth Sonata and Dmitri Shostakovich’s D minor Prelude and Fugue, by contrast, are completely pianistic — although the chord structures in the first movement of the sonata and the fugue’s massive ending could certainly be construed as implications of orchestral sonority. Both composers were outstanding pianists, and the instrument appears prominently on both of their work-lists.

Pictures at an Exhibition was inspired by the death of Mussorgsky’s friend Viktor Hartmann in 1873. The following year, St. Petersburg housed a memorial exhibition of this painter/architect/stage designer’s works. Mussorgsky’s attendance at the exhibit produced two memorial compositions: this piano suite and his Songs and Dances of Death for bass voice and orchestra.

It’s interesting to observe a difference between Pictures at an Exhibition and Debussy’s Preludes (recorded by Osorio on Cedille Records CDR 90000 098), which also evoke pictorial images, including a sunken cathedral, fog, and Dickens’s Mr. Pickwick. Debussy appended his descriptive titles only after he’d written the music, and while they may remain in our thoughts as we listen, we don’t necessarily need them to appreciate the sounds. Mussorgsky’s Pictures, by contrast, were directly inspired by specific works of art, and his intention was to re-create these visual images in sonic terms. He succeeded brilliantly, whether we hear the suite in its original piano version, Ravel’s orchestration, or the orchestrations by so many others.

The suite is unified by its use of a passage called Promenade, which opens the piece and recurs several times as an interlude between portraits. The Promenade also provides source material for motives heard in the other movements. In the Promenade, we hear and envision Mussorgsky walking around the exhibit hall, perhaps humming to himself. The tune is laid out in irregular meters, so he’s not marching through the galleries, just strolling.

The Promenade gets us under way.

Gnomus is Hartmann’s design for a children’s toy, perhaps a wooden nut-cracker, the figure a humorous caricature of a gnome or elf.

[Promenade]

The Old Castle depicts a watercolor in which we see a castle and a singing medieval troubadour. This movement evokes the gently rocking rhythm of a barcarolle.

[Promenade]

Tuileries: a kind of scherzo with children romping in a famous Parisian park.

Bydlo presents a very different sound world. This picture portrays a Polish farm wagon drawn by oxen that plod along as its heavy wheels drag through the thick mud.

[Promenade]

The Ballet of the Chicks in Their Shells is another scherzo-like interlude, inspired by Hartmann’s drawings of costumes for a ballet. The chicks dance playfully for about a minute, chirping all the while.

Once again the mood shifts as we visit a Jewish ghetto somewhere in Poland; the characters in this sharply-etched dialogue are a rich merchant, Samuel Goldenberg, and his poverty-stricken companion, Schmuyle.

Promenade

From Poland we return to France, for The Market-Place in Limoges. A third scherzo, this depicts not children or chicks but bustling women selling their wares at the famers’ market.

Catacombs and With the Dead in a Dead Language are inspired by Hartmann’s self-portrait against the backdrop of the underground catacombs of Paris. In the second portion, the motives of the Promenade are echoed, this time mournfully.

We’re back in Russia for The Hut on Fowl’s Legs. This was inspired by Hartmann’s design for a clock depicting the fanciful home of the Russian witch named Baba-Yaga.

To conclude, Mussorgsky gives us his re-creation of one of Hartmann’s architectural drawings, the full title of which is The Heroes’ Gate in the Imperial City of Kiev. Usually shortened to The Great Gate of Kiev, this towering structure was never actually built. To represent it, Mussorgsky uses powerful repeated chords and heavy octave progressions that proceed to a mighty climax. Incorporating once again the theme of the unifying Promenade, he evokes not only the gigantic structure of the gate itself but also the sound of bells pealing out in triumph.

Winter 1945: Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin at the Yalta Conference; the Battle of the Bulge in Western Europe; Soviet forces moving westward toward Berlin. In January of that year, Prokofiev took the podium at the Moscow Conservatory to conduct the first performance of his Symphony No. 5, in which one can almost hear artillery fire and can definitely sense both the war’s frenzy and its fears. Audience members later recalled that they could hear actual gunfire during the performance: celebration of the news of an important Soviet advance.

Closely contemporaneous with the Symphony No. 5 are three piano sonatas that likewise convey belligerence in their aggressive dissonances and strong emotions. Hence the Sonatas Nos. 6, 7, and 8 have come to be known as Prokofiev’s War Sonatas.

Earlier works than the Fifth Symphony, these sonatas date from 1939 and 1940, a time when the composer was beleaguered with troubles. His marriage was in jeopardy because of his love for another woman; a friend and close collaborator was inexplicably arrested and disappeared; and he’d been asked to write an homage to Josef Stalin, a superficially upbeat cantata known in English as “Hail to Stalin.” According to Prokofiev biographer Daniel Jaffe, the composer subsequently “expressed his true feelings” with the sonatas. Since two of them later won Stalin Prizes, it appears the Soviet music czars didn’t listen very perceptively.

“Brutal” is a word often used to describe the harmonies and textures of the War Sonatas. Certainly they are forceful — at one point in No. 6’s Allegro moderato first movement, the performer is directed to punch the keyboard with his fist. But brutality is not the intention. “Implacable” might best describe this movement’s sense of inevitable forward propulsion, its mood and themes dominated by the assertive opening rhythmic motive. The movement’s almost ceaseless energy and drama are occasionally interspersed with quieter moments, but the overall sense is one of demonic power.

Prokofiev cast his Sonata No. 6 in four movements, mimicking the structure of some of Beethoven’s big sonatas, and he uses this expanded layout to convey a wide range of moods and emotions. In the Allegretto second movement, a kind of scherzo, the mood is light-hearted compared to the Allegro, but even here a sense of discontent creeps in due to its wandering tonal centers. More straightforward is the Tempo di valzer lentissimo (very slow) that has a soft dynamic throughout. In this waltz, Prokofiev speaks frankly of human feelings and longings, reminding many listeners of his Romeo and Juliet ballet music. The sonata’s finale, Vivace, returns to the almost incessant percussiveness of the first movement, while also recalling some of its themes. The sardonic flavor of the composer’s early piano Sarcasms, Op. 17 is felt here in the movement’s towering chords and crashing dissonances that threaten to spin off into chaos.

“A theme is an elusive thing,” Prokofiev once remarked. Perhaps for this reason, he always carried notebooks to record any musical idea that might occur to him (akin to Beethoven’s famous sketchbooks). And like Handel, his predecessor by some 200 years, Prokofiev hated to waste a good tune. He returned to youthful pieces for sonatas subtitled “From Old Notebooks”; he re-used ballet music in chamber music; and he created orchestral suites from operas and ballets — suites that are more often-heard than the original large-scale works. As noted before, the piano suite called Ten Pieces from Romeo and Julietarose partly because of difficulties and delays in getting the complete ballet performed. The movements chosen for piano reproduction only vaguely follow the sequence of the ballet movements and the story. Instead, they’re a study in contrasts: the violence of the Montague-Capulet feud juxtaposed immediately with the gentleness of Friar Laurence, for example. Most of the movements — Minuet, Masks, Mercutio — are very short, but in the finale, “Romeo and Juliet Before Parting,” Prokofiev allows a more expansive statement. This final portion of the suite expresses all the tenderness and pathos of the star-crossed lovers. It shows Prokofiev as a composer capable of great lyricism and beauty; no more telling contrast to the powerful Sixth Sonata could be imagined.

Shostakovich produced cycles of symphonies and string quartets, 15 each, that are among the major achievements of 20th-century classical composition. In them may be heard not only his brilliant creativity and compositional skill, but also a kind of history of his tortured, back-and-forth relationship with the Soviet system under which he toiled his entire life (unlike Prokofiev, who left Russia in the wake of the 1917 Revolution and lived in the U.S. and France until returning home in the early 1930s). A rule of thumb in commentary on Shostakovich is that the symphonies represent the public composer while the quartets portray his inner life — and it’s a useful way to look at the works. Another quintessentially personal and private project for Shostakovich was his set of 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87, written in the early 1950s as a kind of homage to Bach.

Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier is a cycle of preludes and fugues in all of the major and minor keys that represents a towering achievement in the history of keyboard composition. Among his successors, Chopin wrote 24 Preludes in all the keys, but did not couple them with fugues. Debussy’s two sets of Preludes were never intended to follow any key progression; their intent was quite different. Shostakovich, who also wrote a set of 24 preludes without fugues, Op. 34, set out to follow the complete Bach model with his Op. 87. It’s been suggested that one inspiration for this set was a trip to Leipzig in 1950, for ceremonies and concerts honoring the 200th anniversary of Bach’s death. Another motivation might have been to challenge himself by creating music in perhaps the strictest form there is: the fugue. Still another was to write a major cycle that would not attract much official notice in the aftermath of the Soviet authorities’ public denunciation of his larger-scale works (e.g., Eighth Symphony) in 1948.

While long regarded mainly as teaching compositions, Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier preludes and fugues are also profoundly musical. Likewise, Shostakovich doesn’t limit himself to technical exercises; he created in his Op. 87 a masterly suite of musical vignettes that sometimes take Russian folk music as their inspiration, and which everywhere show the genius of his musical imagination.

To follow the circle of fifths of traditional Classical-Romantic harmony, you begin with C major and proceed to its relative, A minor, then onward to G major, E minor, and so on. You end with D minor, the relative of F major. Shostakovich’s Prelude and Fugue No. 24 in D Minor is thus the grand finale of the entire set. Both Bach and Shostakovich used a wide range of styles and forms for their preludes; their comparative freedom of structure contrasts strongly with the prescribed layout of the fugues. Shostakovich’s Prelude No. 24 is slow, stately, even majestic, with a subsidiary theme developed in left-hand octaves that the composer transforms into the main subject (theme) of the ensuing four-voiced fugue. After these voices are introduced and combined, Shostakovich proceeds through several key changes and arrives at the rather remote key of A-flat, with a new fugal subject that’s eventually amalgamated with the original one for a striking and powerful conclusion.

Andrea Lamoreaux is Music Director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s Classical Experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 68:55

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded October 27 – 30, 2008, in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago

Cello: Pietro Guarneri II, Venice c .1739, “Beatrice Harrison”

Cello bow: Francois Xavier Tourte, c. 1815, the “De Lamare” on extended loan through the Stradivari Society of Chicago

Steinway Piano; Charles Terr, Technician

© 2010 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 120