Store

Store

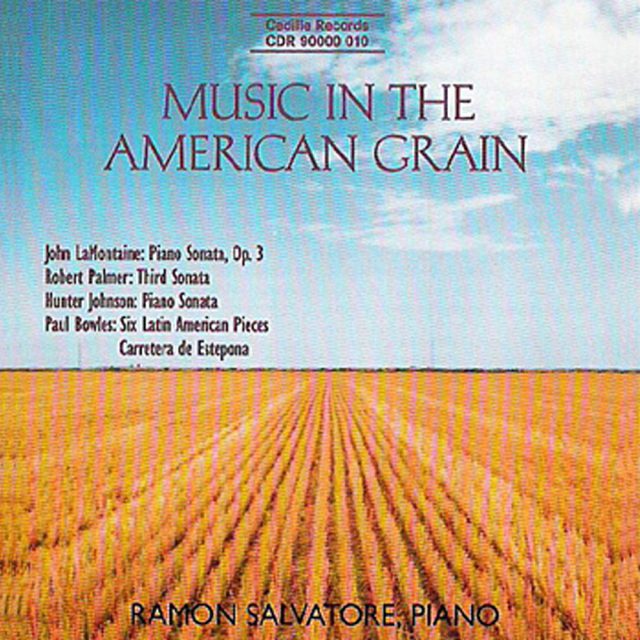

Music in the American Grain

Pianist Ramon Salvatore, a champion of American music, harvests a program of attractive, distinctive yet neglected works by four prominent, living composers on his first recording for Cedille Records.

The disc offers debut recordings of Robert Palmer’s neoclassically seasoned Third Sonata (dedicated to Salvatore) and Paul Bowles’ evocative Carretera de Estepona. Other works include Bowles’ Six Latin American Pieces, John LaMontaine’s dramatic Piano Sonata, Op. 3, and Hunter Johnson’s Piano Sonata, which The New York Times described as “an engrossing combination of Hindemith-like counterpoint and American blues.”

The composers, who received advance copies of the recording, praise it robustly. Palmer notes “a clarity and understanding of every part of the work that is truly outstanding.” He describes Salvatore as a “superb musician” and likens him to the late John Kirkpatrick for his dedication to popularizing neglected American masterpieces.

Bowles calls the recording of his pieces “the best I had heard.” Johnson declares the recording of his Sonata “a knockout in every respect. I would call it definitive — everything exactly right — one by which to measure all other performances of it.” To LaMontaine, it’s “nothing less than stupendous.”

Salvatore’s interest in American music extends back into the 19th century, but he devotes this recording to “a lost generation of works” by American composers whose personal styles blossomed in the 1930s and 1940s — styles marked by new harmonies and rhythms an ocean apart from European influences that once dominated American music.

Preview Excerpts

JOHN LA MONTAINE (1920–2013)

Piano Sonata, Op. 3

ROBERT PALMER (b. 1915)

Third Sonata

HUNTER JOHNSON (1906 - 1998)

Piano Sonata

PAUL BOWLES (1910-1999)

Six Latin American Pieces

PAUL BOWLES

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletMusic in the American Grain

Notes by Monroe Levin

The years 1896-1910 were special for American music. While Charles Ives was using those years to build his insurance business by day and write his body of strange-sounding music after work, four major composers were born: Roger Sessions (1896-1985) in Brooklyn, Roy Harris (1898-1979) in rural Oklahoma, Aaron Copland (1900-1990) in Brooklyn, and Samuel Barber (1910-1981) near Philadelphia.

All of these composers grew up knowing little if anything about Ives’s music. Although Ives published his famous “Concord” Piano Sonata in 1919, America did not hear the piece until John Kirkpatrick gave its first public performance in 1939. Ives’s largest-scale work, the Fourth Symphony, was not performed until 1965, eleven years after the composer’s death.

Instead of seeking out “America’s greatest composer” in his Danbury, Connecticut retirement, Ives’s spiritual successors sought European inspiration. Copland and Harris had lessons at Nadia Boulanger’s Paris apartment; Barber composed his First Symphony in Rome; Sessions came under the influence of Swiss-born Ernest Bloch, who became an American Citizen in 1924.

Still, all four composers felt what Ives had first sensed in the American air. It was not only time to stop emulating German music a la Edward McDowell, but the time had come to replace other national reactions to the Germanic “mainstream” (e.g. those of Debussy, Bartok, Stravinsky) with America’s own.

Sessions evolved from Bloch’s nationalism to a version of atonality that promised exceptional freedom, as well as audience resistance. Barber’s new American Romanticism veered toward an opposite pole. In between stood Copland and Harris. Their transplantation of Stravinsky’s very theoretical, very sophisticated re-shaping of baroque and classical styles eventually drew the label of both names hyphenated; the composers of the next generation represented on this recording have often been called members of the “Copland-Harris” School.

As time passes, however, it is possible to differentiate more clearly between these two ‘schoolmasters,’ and to see why (putting Paul Bowles in parentheses for the moment) John LaMontaine, Robert Palmer, and Hunter Johnson relate more to Harris than to Copland.

All three were, like Roy Harris, alumni of Howard Hanson’s Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY, where an inland variety of modernism prevailed. All tended to follow Harris (and Bela Bartok) in pursuing the elusive spirit of native folksong rather than quote it directly. Apart from Johnson’s Martha Graham ballets (Letter to the World, Deaths and Entrances, and The Scarlett Letter) their work was mainly in the medium of abstract instrumental music – an obvious distinction from Copland.

But more subtle differences lie in the areas of sonority, texture, and phrase structure. Palmer’s typical (he would call it “organic”) way of letting the fugue theme of the Third Sonata slow movement grow from its opening Canzona illustrates perhaps best the tradition Roy Harris exemplified in his Third Symphony: a combination of rhythmic irregularity and austere mood that suggest the rural world as opposed to that of the big city.

Vertically speaking, this Harris brand of rugged Americanism leaves a more sober taste in the ear than Copland’s. Chords like those LaMontaine chooses for the build-up to his final Allegro, or Johnson for the plaintive outcries of pain in his finale, evoke their own expressive intensity. There is joy and triumph in this music of Inner America, but little of Copland’s urbane wit and irony. Paul Bowles, never quite sure if he truly was a composer, has that sense of wit from his teacher, Copland. But Bowles is nonetheless related to Harris by the naive, unpolished flavor that gives his music an invigorating freshness and charm.

Separated in this way, the styles of Copland and Harris met different fates when Arnold Schoenberg’s American disciples began dominating the scene after mid-century. It’s not hard to understand how a public starved for contemporary sounds with genuine emotional content would turn to an Appalachian Spring before a more sober “music of the prairies.” Very little was heard of the sounds of this disc during the 1960’s and 70’s.

Now, as the pendulum continues to swing away from atonality, music of the forgotten Harris-type composer can be re-evaluated. It is not the only “Music in the American Grain,” but its grain is just as much worth exposing – its wood just as durable and maybe a little harder – as that of the music of Sessions, Copland, and Barber.

— Monroe Levin is Music Critic for Philadelphia Jewish Exponent and author of Clues to American Music (Starrhill, Washington, D.C., 1992).

Album Details

Total Time: 60:27

Recorded: Nov. 12, Dec. 16 & 18, 1991 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Photo: Cut Wheat (detail) © Gus Foster

Design: Robert J. Salm

Notes: Monroe Levin

© 1992 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 010