Store

The McGill/McHale Trio, an international all-star ensemble of flute, clarinet, and piano, makes its recording debut with Portraits, featuring world-premiere recordings of new compositions and arrangements for this captivating combination of instruments.

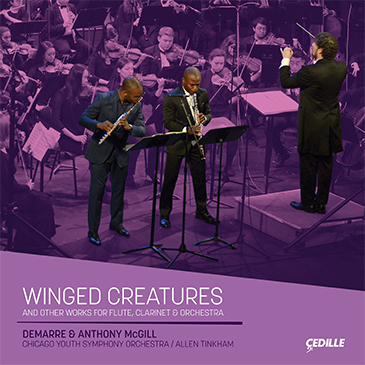

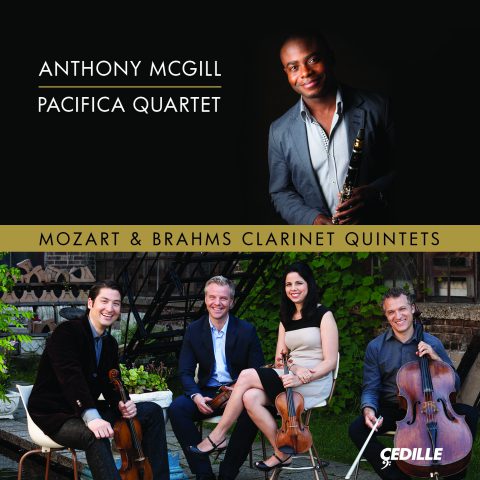

Trio flutist Demarre McGill, a Chicago native, has served as principal flute of the Seattle, Dallas, and San Diego symphony orchestras, as well as acting principal of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.. His brother, Anthony McGill, is principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic and former principal of the Met Orchestra. Michael McHale, one of Ireland’s leading pianists, has performed as soloist with the Minnesota, Hallé, Moscow, and Bournemouth Symphony Orchestras and all five of Ireland’s major orchestras.

The “title track,” Valerie Coleman’s Portraits of Langston is a six-movement suite inspired by Langston Hughes’s poetry. Oscar-winning actor Mahershala Ali (Moonlight) reads a Hughes poem before each movement.

Chris Rogerson’s A Fish Will Rise evokes rippling water and sparkling sunlight. Pianist McHale’s arrangement of Rachmaninov’s Vocalise splits the original vocal line between flute and clarinet, supported by Rachmaninov’s original piano accompaniment. Paul Schoenfield’s spirited Sonatina for Flute, Clarinet and Piano springs surprises on the Charleston, rag, and jig dance forms. Philip Hammond’s The Lamentation of Owen O’Neil and McHale’s arrangement of The Lark in Clear Air are serenely beautiful treatments of irresistible Irish folk tunes. Guillaume Connesson’s Techno-Parade channels the spirit and energy of electronic pop.

Coleman’s Portraits of Langston and Schoenfield’s Sonatina receive their World-Premiere Recordings. These trio versions of Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, Hammond’s The Lamentation of Owen O’Neil and The Lark in Clear Air are also world premieres on record.

Formed in 2014, the McGill/McHale Trio has won critical acclaim for concerts in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington DC, among other cities. The Philadelphia Inquirer proclaimed, “They can play off each other with hair-trigger precision, their blends are … amazing, creating a hybrid sonority I don’t think I’ve previously heard.”

Listen to Steve Robinson’s interview

with Anthony McGill on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

CHRIS ROGERSON b. 1988

VALERIE COLEMAN b. 1970

Portraits of Langston

GUILLAUME CONNESSON b. 1970

SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873—1943)

PAUL SCHOENFIELD b. 1947

Sonatina

PHILIP HAMMOND b. 1951

IRISH TRADITIONAL, ARR. MCHALE

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletPortraits - Works for Flute Clarinet and Piano

Notes by Elinor Olin

The sense of a place is intimately connected to its rhythms, the dynamic patterns that transport us toward imaginings of physical sensation and natural environment. The McGill/McHale Trio has selected music by living composers who inspire the listener to experience a series of multi-sensory portraits, each invoking a compelling sense of place. Poetic references and sonic imagery in each of these works impel us to engage fully with the music, to hear with all our senses.

Chris Rogerson (b. 1988) A Fish Will Rise (2014/2016)

Hailed as a “confident new musical voice,” Chris Rogerson’s music has been praised for its “virtuosic exuberance” and “haunting beauty” (The New York Times). Born in Amherst, New York, Rogerson started playing the piano at the age of two and the cello at eight. Rogerson’s music has been programmed by numerous orchestras, including the San Francisco, Atlanta, and Houston Symphonies. His compositions have also been performed in New York’s Alice Tully and Carnegie Halls, the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and Symphony Center in Chicago.

Within his already-substantial repertory, Rogerson’s chamber music especially reveals his deep connections with the environment. From Constellations for clarinet, viola, and piano (2015) to Summer Night Music for piano quartet (2012) and Noble Pond for orchestra (2009), Rogerson deftly communicates the multi-sensory immediacy of natural surroundings through a remarkable variety of sonic means.

Rogerson originally scored A Fish Will Rise for piano trio as the first movement of his River Songs (2014). Anthony McGill, who premiered Rogerson’s 2016 clarinet concerto Four Autumn Landscapes, asked the composer to re-orchestrate the movement for flute, clarinet, and piano to feature the McGill/McHale Trio.

The work’s title comes from Norman Maclean’s memoir A River Runs Through It. From the beginning of the movement, Rogerson’s fluid piano ostinato draws us into a sonic virtual reality of rippling water and light. The spontaneity and dynamism of nature are conjured up as the clarinet glides into the piano’s pitch stream and the energy of the flute’s exclamations increases rhythmic momentum. The three instruments are seamlessly intertwined, frequently changing roles of ostinato, main melody, and rhythmic interpolation. The opening section is the source (recalling the original French word’s meaning, “well-spring”) for the elements and structure of the piece. Recurring cycles of tranquility and surging energy alternate before ending in the contemplative mood of the beginning. In the most energetic sections, there are echoes of the open sonorities and motor rhythms often applied by America’s master depicter of nature through music, Aaron Copland.

Rogerson effectively conveys the invocation of A River Runs Through It that “there [is] no clear line between religion and fly fishing.” This music strengthens the connections between nature, music, and spirituality, invoking the optimistic perspective that (paraphrasing the final thoughts of the memoir) like a fish, hope will rise.

Valerie Coleman (b. 1970) Portraits of Langston (2007)

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, composer-performer Valerie Coleman began her music studies at the age of eleven. By age fourteen, she had written three symphonies and won several major performance competitions. Today, she is the founder, composer, and flutist of the Grammy-nominated Imani Winds, one of the world’s premier wind quintets. As a creative force behind her ensemble, she has created a powerful legacy within chamber music, much of which has become standard repertoire for woodwinds. The New York Times praises Coleman’s works as “skillfully wrought, buoyant music.” The composer describes the compass of her works as including flute sonatas telling the stories of trafficked Africans during Middle Passage, orchestral and chamber works based on the experiences of nomadic Roma tribes, and scherzos about moonshine in the Mississippi Delta region.

Portraits of Langston is a six-movement suite calling for virtuosic dexterity and ensemble subtleties from flutist, clarinetist, and pianist alike. Coleman’s trio calls for an extraordinary range of expression — from introspective reflection, to whimsical banter, to shared frenetic anxiety. Each movement contemplates a selected Langston Hughes poem, intended to be read in tandem with performance. Coleman’s notes to the score explain that she was inspired by Hughes’s eye-witness experience of the legendary artists and places associated with the Harlem Renaissance and Parisian cabarets of the 1920s. “The imagery that Hughes provides gives me quite a historical palette…. Stylistically, this work incorporates many different elements that are translated into [music for flute, clarinet and piano]: the stride piano technique, big band swing, cabaret music, Mambo, African drumming, and even traditional spirituals.”

The score provides highly descriptive performance indications such as Sensuous, Frantic!, Majestic, and Poignant, while individual players are directed to convey even more specific extra-musical ideas. The flutist is encouraged to emphasize an accented note “like a kick!” The clarinetist is directed to play certain passages “like a djembe drum.” The pianist is sometimes instructed to emulate choral singing, and elsewhere to make a chord “twinkle.”

“Prelude: Helen Keller” begins with the solo clarinet emerging from nothingness, finding light within darkness as expressed in the poem’s opening lines. The flute joins in with its own version of the clarinet’s soaring melody, an equal partner in this duo giving voice to the poem’s “message of the strength/Of inner power.” The prelude ends with the two instruments joining together in unison rhythms, moving from their lowest registers to highest tessituras and a forte declaration that there is a great deal yet to be heard.

Coleman’s second movement, “Danse Africaine” explores the many implications of its title. Beginning mysteriously, with unpredictable rhythms in all three instruments, it unfolds in contradiction to preconceived notions of dance. Although the Hughes poem begins with a slow and steady pulse, Coleman seems more interested in the character of the dancer, whose enigmatic movements are “like a wisp of smoke around the fire.” The music grows in intensity as layers of complex rhythms are stacked into an intricate textural web — the essence of African polyrhythms. The movement continues with abrupt interchanges between agitated exuberance and exhausted repose. In the end, sustained notes at extreme ranges for all three instruments express the stillness that follows unrestrained, passionate exertion.

“Le Grand Duc Mambo” is introduced in Coleman’s score as “a jazz cabaret club in the red-light district of Montmartre where Langston Hughes worked as a busboy for 25 cents a night.” This high-spirited duet depicting “a terrific fight in the Grand Duc” showcases the technical facility of flute and clarinet, each instrument taking its turn at a syncopated ostinato accompaniment while the other playfully explores the freedom and exhilaration of unrestrained melodic invention. As listeners, we find ourselves somehow transported back to the 1920s, observing the melée and taking in the hijinks of the Parisian demi-monde.

The fourth movement begins as a chorale, with stately blocks of harmony in the piano establishing a mood of calm nobility. Hughes’s poem “In Time of Silver Rain” was written in dedication to Lorraine Hansberry as an affirmation of life during her struggle with cancer. Coleman’s music begins quietly with a continuously flowing line handed off between flute and clarinet, in accompaniment to the piano’s dignified chords. Improvisatory solos in the winds are soon joined by the piano, building an insistent sense of optimism. The movement ends with a confident and affirmative flourish in the woodwinds, solidly endorsed by the piano.

The score of “Parisian Cabaret” instructs the performers to play “With a brisk stride piano feel.” After an appropriately wide-ranging, syncopated piano introduction, a playful clarinet melody is joined, somewhat unexpectedly, by the impish sound of a piccolo. The two woodwinds romp together in parallel lines as the piano consolidates its stride rhythms. After a moment of cantabile introspection, all three instruments start to tear it up, trading enthusiastic riffs in response to Hughes’s command, “Play that thing, jazz band!”

The final movement of Coleman’s suite, “Harlem’s Summer Night,” begins with a wistful flute melody accompanied by atmospheric piano chords, gratifying the images of loneliness and “aching emptiness” in Hughes’s poetry. The music grows toward the fullest and richest textures of the work as flute, clarinet, and piano each pursues its own separate, but coordinated melodic and harmonic identity. As the work comes to a quiet conclusion, Coleman closes the circle of images — darkness to light, nature as emancipator, and strength “through the soul’s own mastery” — introduced in the first poem of the cycle.

Using a visual metaphor, the genre designation of “portrait” for a musical work, Coleman encourages the listener to respond on multiple levels. The impressions conveyed by spoken words in the poetry, enhanced by the aural cues of jazz and ad lib vocal call-and-response, brilliantly express the intersection between here and hear. Portraits of Langston articulates a declaration of “hear me/here I am,” inspiring each listener’s individual, eye-witness experience of the moment that is now.

Guillaume Connesson (b. 1970): Techno – Parade (2002)

Hailed as a revolutionary whose music is written in collaboration with the most accomplished musicians, Guillaume Connesson has effectively captured the attention and curiosity of a broad listening public. With “profound disregard for musical boundaries and taboos,” Connesson’s music “reflects the complex mosaic of the contemporary world” (Bertrand Dermoncourt). After studies at the Paris Conservatoire, where he was awarded Premiers Prix in choral conducting, music history, analysis, and orchestration, Connesson has been on the faculty of the Conservatoire Régional d’Aubervilliers–La Courneuve.

His catalogue of works is expansive and varied, comprising symphonic works (including Pour sortir au jour, a 2013 commission from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra), an opera, a cappella motets for mixed voices, film music, and a significant repertory of chamber music. Many works in Connesson’s oeuvre are compellingly rhythmic; dance fever has been a through-line, as evident in titles such as Night Club for orchestra (1996), and Disco-Toccata for Clarinet and Violoncello (1994), and Techno-Parade (2002).

Techno-Parade opens with driving repetitions and virtuosic riffs conveying the relentless excitement of techno music. Yet this is an ironic take on the electronic music genre. Unpredictably shifting meters, occasionally settling into an uneven if temporarily constant feeling of 7/4, are in alternation with passages lacking the comfort of any obvious downbeat. In the middle of the piece there is a percussion break, where the pianist uses a wire brush and places sheets of paper directly on top of the piano strings.

The composer explains “[Techno-Parade] was written with a continuous pulsation, from start to finish. There are two decisive motives, swirling and colliding together, giving the piece its character, festive and disquieting at the same time. The wailing of the clarinet and the obsessive patterns of the piano seek to recapture the fierce energy of techno music… The three instruments seem drawn into a rhythmic trance that carries the piece to its conclusion in a frenetic tempo.”

Extended techniques and extreme ranges for the winds create a changing constellation of colors and textures, compelling the listener toward increasing levels of participation. Maybe you can’t dance to it, but one thing is sure: this music moves.

Serge Rachmaninov (1873–1943) Vocalise, arranged by Michael McHale (1912/2016)

Serge Rachmaninov was one of the greatest pianists of his time, trained in the late Romantic tradition of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and the stylistic heir to Anton Rubinstein and Piotr Tchaikovsky. It’s no surprise that many of Rachmaninov’s works feature the piano and were written to showcase the composer’s own technically brilliant performance skills. Another side of Rachmaninov’s musical personality is heard in his nearly 100 songs, especially the collection Op. 34, dating from 1910–1912. The most famous of these is the Vocalise, No. 14 in the set, written for Russian soprano Antonina Nezhdanova. Known for her clear tone and agile coloratura technique, Nezhdanova must also have been gifted with tremendous breath control. The song’s long, wordless vocal lines rely on melodic phrasing technique, continuity, and shading of tone color rather than diction of words for communicative effect. Michael McHale has translated the flowing, legato phrases of the original vocal line into alternating melodies for flute and clarinet, supported by the gentle rhythmic continuity of Rachmaninov’s original piano accompaniment. Each wind instrument takes a turn at the soprano line while the other adds timbral richness. The instruments achieve full resonance as the winds soar in unison at the highpoint of the song, carrying the single vocal line together in a compelling and expressive transformation of breath into melody.

Paul Schoenfield (b. 1947) Sonatina for Flute, Clarinet and Piano (1994)

Paul Schoenfield began his musical career as both pianist and composer, writing his first work at the age of seven. Following studies with Rudolf Serkin and Robert Muczynski (piano and composition, respectively), Schoenfield has held several teaching posts and worked as a freelance performer and composer in the U.S. and Israel. Schoenfield’s experience as a piano soloist and chamber musician has unmistakably informed the immediacy of his compositional styles. Schoenfield writes the kind of music that combines intriguing complexity with a deceptive ease of accessibility. His works draw the listener in, stimulating our attention in a friendly rather than demanding manner. Drawing on popular and folk traditions, in combination with the “serious” techniques of Western art music, the energy of Schoenfield’s music conveys both the excitement and the meditative focus of the performer’s experience — all in a single work.

Schoenfield has remarked that his “is not the kind of music to relax to, but the kind that makes people sweat; not only performer, but audience.” Sonatina for Flute, Clarinet and Piano is a fine example of this perspective. Titles for the three movements refer somewhat deceptively to types of dances. The slow opening to “Charleston” is evocative and moody, with uneven metrical changes that discourage foot-tapping or other dance moves. The music builds toward the lilting rhythms of the Charleston dance, but not without a good measure of irony (the score is occasionally marked “Puckish”) setting character and attitude for the balance of the work. Fluctuating between swinging, syncopated rhythms and an intentional destabilization of metrical regularity, in combination with lyrical and sustained melodic lines, “Hunter Rag” and “Jig” (the second and third movements, respectively) continue to undermine the listener’s anticipation of dance moves implied by the movement titles. Each of the instrumentalists is “made to sweat” with a virtuosic array of notes, unexpected harmonic patterns, and overlapping layers of considerable rhythmic intricacy. Changing tempos, deconstruction of dance patterns, and abrupt registral shifts in quick succession all contribute to the subversion of expectations in a work that is both high-spirited and thought provoking.

Philip Hammond (b. 1951) The Lamentation of Owen O’Neil (2011/2016)

Belfast-born pianist/composer Philip Hammond remembers being fascinated by clefs, especially the bass clef. His first piece, written at age six, was Sputnik, a study of the nether regions of the keyboard. “Something of a contradiction in terms,” he muses in retrospect. Since then, Hammond’s career has successfully integrated teaching, performing, and writing. His work as a broadcaster and composer has brought him regularly before the public on radio and television, as well as on the concert stage. Hammond describes his music as unabashedly emotional and deeply influenced by poetic traditions. He attributes a “retro-romantic” inclination to his years in Northern Ireland where “we all lived in a fantasy world of violence, but which some of us were able to blank out totally. At least on the surface of our existence.”

The Lamentation of Owen O’Neil is Hammond’s rumination on an 18th-century air attributed to legendary harpist and bard Turlough O’Carolan (1670–1738). First published in 1796 as part of a General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music, this ballad commemorated the passing of an early hero of Irish nationalism. Hammond’s tribute to O’Carolan’s lament opens with a quotation of the time-honored melody, eliciting the improvisational tradition of bardic performance in shifting time signatures of two, three, five, and seven. Sotto voce entrances of flute and clarinet are accompanied by the piano in layered fragments of the pensive tune, along with quiet interpolations evoking a Celtic harp. Hammond originally wrote Lamentation of Owen O’Neil in 2011 for two flutes and piano, premiered by Sir James Galway, Lady Jeanne Galway, and Michael McHale. Hammond created this new arrangement for flute, clarinet, and piano expressly for the McGill/McHale Trio.

The Lark in the Clear Air, Irish Traditional, arranged by Michael McHale (2016)

According to her 1896 biography, Lady Mary Guinness Ferguson hummed the tune of an Irish air to a Swedish harpist visiting her Dublin home. The visitor was so captivated by the melody that he convinced his host, Sir Samuel Ferguson (1810–1886), to write new lyrics for it. First published as a “very ancient” tune, “author and date unknown,” the melody was included in an 1840 collection as “Kitty Nolan.” More recent research identifies the title of this ancient air as an Anglicization of “Caitlin Ní Uallachaín,” the text of which had been a plaintive call for Irish independence.

Ferguson’s poem, The Lark in the Clear Air, in celebration of springtime and love, became the vehicle for the older, traditional tune and was performed as such in late-19th century festivals devoted to music for the Ancient Celtic harp. Subsequently, the song has been embraced by many generations of musicians and has become a staple of Irish traditional repertory. Michael McHale’s new arrangement for flute, clarinet, and piano features three verses, with each instrument taking a turn on the tune. The woodwinds incorporate the melodic embellishments of traditional Celtic music and the piano carries them forward to invoke the sounds of nature.

Dr. Elinor Olin is a professor at Northern Illinois University School of Music and has a background in both music performance and music history.

Album Details

TT: (66:17)

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded December 19–21 2016, at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, University of Chicago

Steinway Piano

Piano Technician Ken Orgel

Graphic Design Rubric

Cover Photo “McGill/McHale Trio” by Matthew Septimus

© 2017 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 172