Store

Poetry inspired remarkable trios by three Romantic composers: August Klughardt’s Schumannesque Schilflieder (Songs of the Reeds) from 1872 tell the poignant story of a man ‘reunited’ with the ghost of his lost love. American composer Charles Martin Loeffler’s Two Rhapsodies for Oboe, Viola, and Piano (1901), also inspired by love lost, offers a delightful blend of French Impressionism and New World freshness. British composer Felix White’s evocative The Nymph’s Complaint for the Death of her Fawn (1921) won a Carnegie Award and the admiration of Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Also on the disc are Marco Aurélio Yano’s beautiful transformation of a melody from his native Brazil, titled Modinha (1984), and Paul Hindemith’s extraordinary Trio for Viola, Heckelphone, and Piano, Op. 47 (1928), which sizzles with a dramatic modernism all its own.

All receive inspired performances by renowned oboist Alex Klein, former principal of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and his friends Richard Young, violist of the venerated Vermeer Quartet, and Brazilian pianist Ricardo Castro, winner of the 1993 Leeds International Piano Competition.

Preview Excerpts

AUGUST KLUGHARDT (1847–1902)

Schilflieder (Songs of the Reeds), Op. 28 (1872)

CHARLES MARTIN LOEFFLER (1861–1935)

Two Rhapsodies for Oboe, Viola, and Piano

FELIX WHITE (1884–1945)

MARCO AURÉLIO YANO (1963–1991)

PAUL HINDEMITH (1895–1963)

Trio for Viola, Heckelphone,and Piano, Op. 47, Erster Teil

Trio for Viola, Heckelphone,and Piano, Op. 47, Zweiter Teil: Potpourri

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletModinha by Marco Aurélio Yano

Notes by Alex Klein

Marco Aurélio Yano wrote Modinha in 1984 as a friendly gift to me. We were both attending college composition classes at the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP) in São Paulo, Brazil. Marco wrote for this combination as an addendum to the limited repertory for oboe, viola, and piano, after I first discovered the Loeffler Rhapsodies. Modinha is a common term used to describe a traditional melody in Brazil.

Marco generously wrote short works for several of his colleagues, including works for viola, dedicated to our friend João Mauricio Galindo, and the two solo oboe works he wrote for me (Seresta and Improviso). A few years later, it was my recollection of these beautiful works and his labor of love that inspired me to commission a new oboe concerto from Marco. It was to be his first and only large scale work. (I recorded Marco’s Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra for Cedille Records in 2003, with Paul Freeman leading the Czech National Symphony Orchestra.)

Yano was a nissei, the name used to describe the first generation of Japanese immigrants born in a foreign land. Brazil received a large influx of Japanese nationals in the last century and boasts the largest Japanese community outside of Japan. Marco Aurélio Yano was a member of this tightly knit community. The influence of Japanese culture is not difficult to hear in his music, as a distant calling in the way he delineates his phrases, in the passing nostalgia of his musical characters, and in the way he treats all climaxes within the work.

What is most striking in Marco’s music, both here and in the Concerto, is the depth of his involvement with it even where it relates to music written for friends. Perhaps one would expect such music to express the camaraderie we see in works other composers wrote for their close buddies: an inside joke or two, or a reference to a particular quirk of the dedicatee’s personality. We see this in Mozart, Brahms, and Nielsen (for example) when a close friend is the inspiration for a work. Not so with Yano. Music for him was an escape, a closely guarded form of expression in a world which had denied him other means of movement.

It would be improper to mention Yano’s physical condition as means to magnify his musical talent, or to give it special value. Doing so would belittle his work, if not insult it. Yet the two — the talent and the condition — need to be addressed to understand the reality from which Marco created his music. Marco was quadriplegic from birth, which gave him a perception of our world the rest of us cannot begin to comprehend. Speech, movement, motor control, and the expression of common emotions took on a burden capable of muffling emotional and artistic output — or in the case of Marco, providing an avenue of expression that was all his, arguably the only one freely given to him (other than the constant support and love of his parents and family). Yano’s short life (1963-1991) is remembered in the few works mentioned here, and also several pieces for electronic media.

Schilflieder (Songs of the Reeds), Op. 28 by August Klughardt

Notes by Richard Young

This recording project has revealed a number of unexpected treasures, the most unlikely of which might be Schilflieder because August Klughardt is virtually unknown today, even among most professional musicians. During his career as a Kapellmeister in Posen, Neustrelitz, Lubeck, and Dessau, he wrote numerous operas and symphonic works and some chamber music. Not one of his compositions has found its way into the standard repertoire, however, although his woodwind quintet is occasionally mentioned by wind players. Nevertheless, despite its obscurity, this piece for piano, oboe, and viola is hauntingly beautiful and deserves to be heard.

Schilflieder (Songs of the Reeds) was composed in 1872 in a grand romantic spirit reminiscent of Franz Liszt, to whom it was dedicated. Its five pieces are based on poems by Nikolaus Lenau, whose verses are printed in the score above the relevant passages. They tell the story of a man who has lost the love of his life. Overwhelmed by despair, he withdraws to a secluded place by a pond where reeds grow in the shallow waters near the shore. Here he grieves and reminisces about his lost love.

From the earliest moments of the first piece, one is overwhelmed by the man’s private pathos. Different memories are subsequently evoked by changes in the weather and the light — as in the second piece, when wind and pelting rain envelop the familiar scene by the pond. The third piece is a hushed and vulnerable dream — a bittersweet recollection of happier days. (Alban Berg used this same Lenau poem for one of his Seven Early Songs.) In the fourth piece, a violent thunderstorm is in full fury when a burst of lightening suddenly illuminates what appears to be the woman’s face reflected in the surface of the pond, her rain-soaked hair whipped about by the howling wind.

As colorful and dramatic as the music has been thus far, Klughardt saves the best for last. For in the fifth piece, the two lovers appear at last to “talk” to each other! After a soul-wrenching outpouring in the viola comes a heavenly 2-note “cry” in the oboe. Just as Robert Schumann evokes his beloved “Cla-ra” with a 2-note falling fifth (in his third string quartet and the piano quintet), the woman here calls out with a 2-note falling sixth. What follows is a touchingly poignant “conversation” — his still-tormented soul expressed by the viola, her more reassuring voice by the oboe. The two eventually “harmonize” one another in music of sincere and heartfelt rapture. And in one extraordinary moment near the end, just after “a quiet evening prayer,” the oboe’s tender melody is seamlessly passed to the viola, as though the lovers’ salty tears are mingling one last time. All prior despair is reconciled as this deeply moving work concludes with a soft but wistful “cry” — yet again, a falling sixth.

The Nymph's Complaint for the Death of her Fawn by Felix White

Notes by Ricardo Castro

Throughout music history there have been many fine musicians who were more talented than successful. One such was British composer Felix White, who wrote a surprisingly large number of works, few of which were known beyond his own circle of friends and associates. Today, over a hundred of his compositions are listed in the British Library’s catalogue of British music, including symphonic poems, chamber music, songs, pieces for string orchestra, and solo piano works. He also orchestrated many piano pieces, including Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. Though he was labeled “one of the most characteristic” English composers during the 1920s, this is a far cry from the praise that others of similar ability received at the time.

Why is this? First of all, White never wrote a major symphony or choral work — the kind of music that might have made a grand impression on the British public. Moreover, none of his music was recorded during his lifetime and relatively few works were published. Most have existed solely in manuscript form, only occasionally acknowledged in the small print of music journals or library catalogues. Even a Google search has little to offer about Felix White. His greatest public success probably came during the 1930s, when the BBC finally aired a couple of his pieces. Though he had submitted countless others, they had all been rejected or were never performed.

Sadly, this has been the reality faced by many struggling composers, before and after Felix White. They have found themselves caught in the middle of two questions that pull in opposite directions: How can you become well known unless you receive important performance and recording opportunities? But how can you get these opportunities if you are not already well known? As a consequence, composers toil all too often in obscurity, taking music-related jobs as they come along. They try to take advantage of their limited access to the “music establishment” — sometimes through colleagues who (for reasons that are often inexplicable) have become relatively successful. They knock on many doors, figuratively and literally, but for the most part end up living in the shadows of the music profession. Their greatest satisfaction is more private than public — derived from the conviction that they have written music that is worthy, even if it is not successful.

Felix White was born into a Jewish family whose original name was Weiss. He was entirely self-taught, except for piano lessons he received from his mother at an early age. In 1931, he joined the London Philharmonic Orchestra as the celesta and piano player. He wrote many articles, did a number of translations, and edited works by other composers. Hopes were high when John Barbirolli asked him to write a Poem for cello and piano — a work White considered one of his very best. But any chance this might have led to important future opportunities vanished when Barbirolli gave up the cello to pursue his hugely successful career as a conductor. Neither Barbirolli nor anyone else (to our knowledge) ever performed the piece in public.

Perhaps the only reason The Nymph’s Complaint for the Death of her Fawn is known to us today is that it won a Carnegie Award in 1922. This, in turn, brought it to the attention of Ralph Vaughan Williams, who praised it. If not for that, it would probably have been long forgotten, along with most of White’s other efforts. The piece is based on a psychologically complex poem by Andrew Marvell. Unlike Klughardt’s Schilflieder, the music appears to be influenced by the words in mostly general ways rather than by specific references. Nevertheless, the listener can follow the poem’s dark and tragic story. The work is in three parts. It begins with a slow and anguished lament (Andante con moto), proceeds to a nervous and breathless chase (Allegro molto vivace), then returns (Come Prima) to the tortured character of the beginning. It is colorful, evocative, and very skillfully composed — certainly deserving far more attention than it has received.

Trio for Viola, Heckelphone,and Piano, Op. 47 by Paul Hindemith

Notes by Richard Young

The respected American composer Otto Luening once told me about an interview of Paul Hindemith he conducted for The New York Times. Otto was an engaging and trust-inspiring gentleman who made you feel immediately comfortable. But in unguarded moments, you could find yourself revealing things you would normally never share. This must have been what happened when he got Hindemith to admit, “Eighty percent of my music is crap!” Otto earnestly followed up: “Then why did you write it, Paul?” Hindemith thought for a moment, then said something you’d not likely find in a music history textbook, program notes for a CD, or The New York Times for that matter: “I had to write that eighty percent in order to come up with twenty percent that’s really pretty good.”

Paul Hindemith was not the only famous composer who was at his very best only a small percent of the time. This is difficult to prove, however, since most composers tend to withhold pieces that don’t represent their highest standard. This was true of Brahms, for example, who discarded many compositions he considered unworthy. But Hindemith published virtually everything he wrote. This helps explain the noticeable gap between works like the gorgeous Op. 11, No. 4 viola/piano sonata, and the clever but singularly unbeautiful octet. Hindemith’s music was always highly intelligent. Indeed, there was no finer craftsman in the 20th century. It was not always inspired, however — as he admitted to Otto Luening with such unvarnished candor. Nevertheless he saw this as a necessary consequence of his personal “creative process” — a process that might not have been so different from that of other great composers. Hindemith just allowed us to see more of it.

Like the Op. 11, No. 4 sonata, the magnificent Op. 22 string quartet, and orchestral works such as Mathis der Maler, this Op. 47 Trio for Viola, Heckelphone, and Piano is definitely in the twenty percent category that is not just “pretty good,” but truly extraordinary. Composed in 1928, it sizzles with drama from beginning to end. One reason might be that Hindemith was excited by the colorful new possibilities of the heckelphone — a double-reed instrument introduced by the Heckel bassoon company in 1904 and first used the following year by Richard Strauss in the opera Salome. Because the heckelphone’s baritone range falls somewhere between the bassoon and the English horn, the viola is here able to transcend its traditional inner-voice role to find itself perched atop the ensemble texture much of the time. But Hindemith must have felt there should be certain “virtuosic responsibilities” required of those who are allowed to breathe that rarified air normally reserved for first violinists. As a very skillful violist himself, he knew how to exploit and radically stretch the viola’s technical range to a degree rarely seen in the standard chamber music repertoire. In fact, this trio requires uncommon virtuosity from all three instrumentalists. But it always strives to achieve a balance between expression and technique, between emotion and logic, between fantasy and structure — which is a hallmark of the very best chamber music.

The Op. 47 trio has tremendous variety packed into a tight and efficient framework. It consists of two large parts, each of which is divided into smaller sections. The First Part (Erster Teil) begins with a wild, schizophrenic Solo for piano. Though brief, it contains virtually all the “musical DNA” Hindemith employs through the rest of the piece. Next comes a brooding Arioso for heckelphone and piano, followed by a more animated and disquieting Duett for viola and heckelphone with piano accompaniment.

The Second Part (Zweiter Teil: Potpourri) consists of four contrasting sections, played without pause. The first section (Schnelle Halbe) relies heavily on contrapuntal techniques such as fugue and canon. Its angular and confident theme is independently embossed over a strict five or six-note ostinato in the piano’s left hand. This is later contrasted by nervous figures that scurry and scuttle about. The second section (Lebhaft — Ganze Takte) continues the same metric pulse in a similar robust fugal style. But here the additional layers of music contribute even more contrast and drama. The effect is similar to what one hears in culminating choruses of Mozart operas — where individual characters have their own unique style, pace, and temperament as they sing simultaneously from different parts of the stage. After a light and capricious beginning, the third section (Schnelle Halbe) grows increasingly ominous. It is suddenly interrupted by a loud sustained tritone in the piano that serves as a connection to the fourth and final section: a dangerous Prestissimo. Hearts pounding, the three players gradually thicken the texture and broaden the tempo before triumphantly converging on a fortissimo unison C-natural.

Two Rhapsodies by Charles Martin Loeffler

Notes by Richard Young

Of all the works on this CD, this comes closest to occupying a place in today’s “standard repertoire.” It turns up with surprising frequency, not only on mixed chamber music programs that have become the norm at so many summer festivals, but also at conservatory concerts and viola and oboe “congresses” the world over. In fact, violists and oboists have probably played this piece more often than any other chamber work that combines these two instruments — with the possible exception of the Mozart oboe quartet.

Until fairly recently, it was widely believed that Charles Martin Loeffler was born in Alsace (France) to German parents. Throughout his long and successful career, his “cosmopolitan” upbringing and the “typically Alsatian character” of his music were often mentioned. Loeffler himself did little to discourage these misleading impressions. He rarely admitted that his actual birth name was Martin Karl Löffler, that he was born in Schöneberg, not far from Berlin, and that both sides of his family were of Prussian origin. It was some years after the Prussians imprisoned and tortured his father that Loeffler turned his back on his true ancestry and “became” Alsatian. This helps to explain his musical style that was far more French than German.

At age 13, Loeffler resolved to become a professional musician. He studied violin in Berlin with Joseph Joachim and composition in Paris with Ernest Guiraud. At age 20, he emigrated to America, where only one year later he become assistant concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra — a post he held for over 2 decades. This prestigious position enabled him to have numerous compositions performed by that great orchestra, and to be a frequent concerto soloist. In fact, Loeffler gave the American premieres of violin concertos by Saint-Sains, Bruch, and Lalo. He used these valuable opportunities to cultivate personal relationships with many influential musicians including Gabriel Fauré, Ferruccio Busoni, Eugène Ysaÿe, and even George Gershwin. Unlike the unfortunate Felix White, Loeffler was in the right place at the right time, with direct access to the highest echelons of the music profession.

The Two Rhapsodies for Oboe, Viola, and Piano date from 1901. But they were originally conceived in 1898 as a set of Three Rhapsodies for Voice, Clarinet, Viola, and Piano. When the clarinetist for whom they were intended was tragically killed, Loeffler reworked the material so it could be performed by an oboist he had befriended. Based on evocative poems by Maurice Rollinat, the Two Rhapsodies are reminiscent of Fauré and Chausson. The first rhapsody (The Pool) expresses a vivid fantasy-world of “aged fish struck blind, goblins, and consumptive toads,” all under the glow of the moon’s “ghostly face, with flattened nose and weirdly vacant jaw, like death’s head lit from within.” The second rhapsody (The Bagpipe) imitates the characteristic sounds of that primitive yet hauntingly expressive instrument, in a lush setting that could not be more “Romantic.”

Loeffler embraced a musical philosophy post-Romantic literature called “decadent.” He and composers such as Frank Bridge believed that one could not fully appreciate happiness without first confronting the depths of sadness. The promise of “enlightenment” comes only to those who first navigate “the darkness.” In these Two Rhapsodies, Rollinat’s sometimes morbid images should therefore be seen in a larger context — as part of the sometimes harsh and shocking landscape which lines the path that ultimately leads to a more serene and fulfilling destination. Loeffler’s musical expression of this poetry is even more powerful than the words alone. Not unlike a mini-opera, it presents colorful and dramatic tone-pictures that capture the spirit of French Impressionism, but are also imbued with a wide-eyed New World freshness.

The New World had a similar effect on Antonin Dvor´k when he settled in the United States around the same time. But unlike Dvor´k, whose “American” musical language always reflected his Czech heritage, Loeffler rarely allowed the flavor of his music to be influenced by his Prussian origins. Yet if his heart still carried bitterness toward those who took away his father when he was 12 years old, there is no hint of it in his music. For what is so compellingly expressed in these Two Rhapsodies is the wondrous exhilaration, curiosity, and rapture of a young person’s private imaginary realm. Despite all the comfortable trappings of Charles Martin Loeffler’s very successful and satisfying adult life, could this realm have been a still-necessary escape from the nightmares of Martin Karl Löffler’s childhood?

Album Details

Total Time: 67:10

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

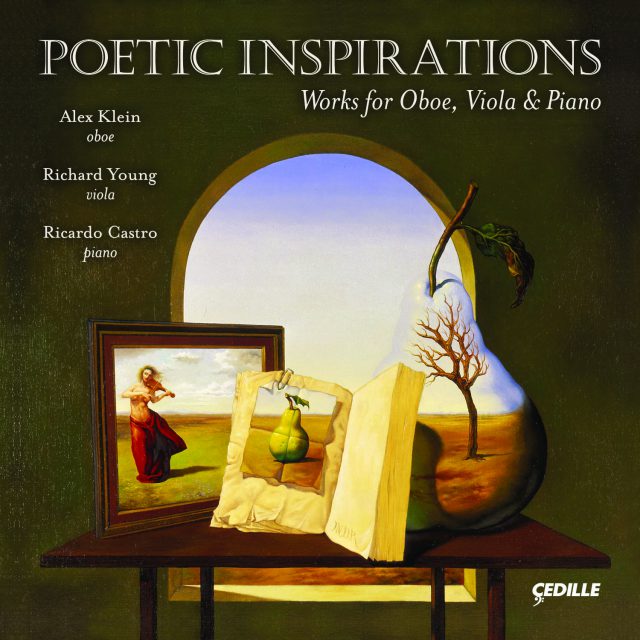

Cover: Immortality by Jose Roosevelt. Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm, 1994. Private collection, Bulle (Switzerland)

Illustrations on pp. 7 & 12 also by Jose Roosevelt

Recorded: April 19, 20, 22 and 23, and October 16-17, 2007 at WFMT, Chicago

Publishers:

Modinha © Marco Aurelio Yano, 1984

Trio for Viola, Heckelphone, and Piano, Op. 47 © B. Schott’s Sohne, Mainz, 1929 © renewed P. Hindemith, 1957

© 2008 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 102