Store

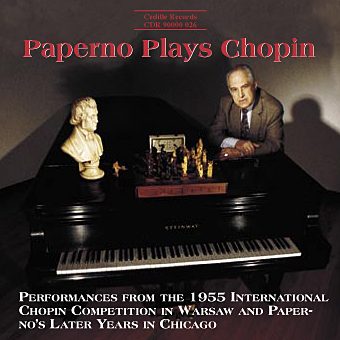

Pianist Dmitry Paperno is delighted when an observer notes similarities between the disciplined power and passion of his playing and the music of Chopin. “It’s my approach to music in general and Chopin in particular,” he says.

A major pianist in Russia in the 1960s and 70s, Paperno has been a lifelong exponent of — but not a specialist in — Chopin’s music. This CD presents performances from the 1955 International Chopin Competition in Warsaw and his later years in Chicago. The CD, Paperno’s fourth recording for Cedille, documents three decades in the evolution of his artistry — all through the works of one composer in recordings of performances never released commercially.

A striking feature of the program is the contrast between the considerably faster playing that prevailed in 1955 and the slower (though hardly slow) tempos heard in Paperno’s concerts recorded between 1977 and 1989 by radio station WFMT.

According to Karp’s Dictionary of Music, “Chopin epitomized the Romantic concept of intimate art. He exhibited a remarkable control over dynamic nuances. Although his music contains many heroic moments, the heroism is an inner personal quality and not a pose to obtain the adulation of the crowd.”

Paperno’s pianism has been described in similar terms. Stereo Review‘s Richard Freed, in reviewing Paperno’s first disc on Cedille, was struck by Paperno’s “affectionate conviction” in what he plays and the “touch of poetry” in his playing. “That quality makes itself felt throughout the entire program, in fact, in the least aggressive way: You feel the pianist is really finding it in the music rather than imposing it from the outside,” Freed wrote. CD Review noted, “Paperno avoids the twin traps of overinterpretation and repression of honest expression.”

The international Chopin Competition still ranks among the world’s most distinguished piano competitions. The Soviet entrants in 1955 felt incredible pressure to make a strong showing: winning an international honor was essential to securing state support as a concert artist. It was a defining moment for the young artists. Paperno’s prize-winning performance at the event launched his concert career.

The CD booklet includes Paperno’s firsthand, behind-the-scenes account of the 1955 competition, which are excerpts from his book: Notes of a Moscow Pianist (Amadeus Press) published in 1998.

Preview Excerpts

FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Artists

1: Broadcast "concerts" for Chicago's Fine Arts radio station WFMT

6: From the 1955 Fifth International Chopin Competition in Warsaw

Stage Two

9: Stage Three

10: Laureates Concert

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe 1955 Chopin Competition

Notes by Dmitry Paperno

Great importance was attached to the Chopin competition, as was obvious from the fact that the winners of two previous competitions were nominated to be jurors — Lev Oborin (the first competition, 1927) and Yakov Zak (the third competition, 1937), who had been remembered and respected in Poland all these years. Only these two of our famous professors had been abroad earlier. The rest of us had never even had the experience of flying. On the night of February 17, 1955, we took off for Warsaw.

After our arrival, the participants were accommodated in the cozy old Hotel Polonia where Rachmaninov used to stay long ago during his tours. In general, for those times, and especially from the point of view of six young Soviet people, the competition was an eye-opening experience. The state took on the expense of accommodating and feeding the almost 150 participants, jurors and guests. One floor of the hotel was set aside for our practising. The rooms were cleared of furniture and several dozen pianos were installed. In one room, Ashkenazy, without sitting down at the piano, let his fingers run through a passage from the Chopin Etude in double thirds (Op. 25, No. 6). A young Chinese man came up and said with amazement, “fantastic!” It was Fu-Tsung, who later became very popular, and won not only the third prize but a special award for the best performance of mazurkas.

Ashkenazy and I were accommodated in a small, one-room apartment. I could not have wished for a better roommate. Despite his young age (17), he was serious-minded, reasonable, well-read, and unassuming in everyday life. Almost always, our evaluations of people and events coincided, and we trusted each other too. When I, as the older one, advised him about something, he usually accepted it. Even today we recollect with pleasure that month when we lived in one room in Warsaw.

For the first time since the War, the competition was to be held in the traditional home of the Warsaw Philharmonic on Yásna Street. The Nazis had bombed Warsaw into ruins, and even ten years after the war, it still hurt to see the destroyed blocks of this beautiful city. The Philharmonic had especially bad luck — shortly before the competition, the recently restored building somehow caught on fire and was urgently under repair again.

Six pianos stood on its huge stage: two Steinways, two Bösendorfers, a Bechstein, and a Pleyel. The Soviet Union had at this time just begun to purchase Steinways from the U.S. and Germany. By the decision of our instructors, we all played on the Steinway-2 (as opposed to the Steinway-1).

The participants performed in alphabetical order, and Ashkenazy astonished everyone on the very first day. He was, I believe, the only contestant who began his performance with highly difficult Chopin études: Op. 10, No. 1, in C and Op. 25, No. 6, in G-sharp. The program for the first stage included any Nocturne, one of the last three Polonaises, a 3-4 minute piece of free choice (I played the Tarantella, Op. 43), and two Etudes from certain groups (two others were to be performed at the second stage).

The impression Ashkenazy made was like a bomb exploding. The contest gained an obvious favorite from the very first day. Among the hundred-some pianists, there were, as always, a certain percentage who seemed to choose for themselves the Olympic slogan: “Participation, not victory, is important.” Indeed, that Chopin’s music was being performed by young pianists from China, Japan, India, Iran, Chile, Ecuador, spoke for itself.

The jury panel was representative and very impressive. Its oldest member, a kind of antiquity, was Emile Bosquet of Belgium, winner of the 3rd International Anton Rubinstein Competition (Vienna, 1900!). It is interesting that the young representatives from Russia who had also taken part in that competition were Nikolai Medtner, who received First Honorable Mention, Alexander Goldenweiser, and Alexander Goedicke, who won a prize in composition. I told Mr. Bosquet that I was a student of his old rival (whom he hadn’t forgotten during those 55 years) and that Mr. Goldenweiser would be 80 in the beginning of March. The kind and sociable Belgian sent a telegram of congratulation to Moscow which brought real joy to my Old Man.

The one representative from France was the small, lively, and talkative Lazar Levy; the famous Marguerite Long did not arrive until the competition was in its third stage — the performance with orchestra. Another colorful figure was Madame Magda Tagliaferro, an invariable representative of Brazil since the second competition in 1932. I still remember her recital — her bright red hair, lots of Spanish music — a lively and consistent performance. How astonishing it was for me when, a quarter of a century later, my friend, Professor Nina Svetlánova, called me up from New York City and announced that she had just heard an amazing old lady, Tagliaferro, perform at Carnegie Hall. As Russians sometimes say, “These people do live” — while the majority of our own do not even reach 70: Sofronitsky, Ginsburg, Oborin, Oistrakh, Shostakovich, Flier, Zak . . .

Similarly, the largest, Polish group had two older men: Jérzy Zhuráwlew of Russian extraction who had founded the Chopin competition (held every 5 years) during the 1920s, and Zbígniew Drzewiecki, a popular teacher from Krakow, through whose hands several generations of Polish pianists had passed.

There was also a distinguished group of laureates from past competitions on the jury. Besides our Lev Oborin and Yakov Zak, there were the Poles, Staníslaw Szpinalski and Henrik Sztompka (the first competition, 1927), a representative from England, Louis Kentner, and the blind Hungarian Imre Ungár (second competition, 1932). By the way, at that competition a 15 point system for the evaluation of playing was used. The winners — Alexander Uninsky (the Russian Jew, who had represented France, and spent his last years in the USA), and Imre Ungar, received the same score. According to the regulations at that time, lots were drawn (we are talking about the 1st prize here!), and Ungar found himself second . . . After that time, a 25 point system of scoring was adopted to reduce the possibility of coincidence.

Another group of jurors were the popular piano teachers — Jacques Fevrier (France), Emil Hajek (Yugoslavia), Frantisek Maxian (Czechoslovakia), Bruno Seidlhofer (Austria), formerly a famous pianist who later switched to conducting, Carlo Zecchi (Italy), the composers Lubomir Pipkov (Bulgaria) and Witold Lutoslawski (Poland). The youngest in the jury were the beautiful Flora Guerra (Chile), and the strange, reserved Italian Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. All we knew about the latter was that he had received the seventh prize in Brussels in 1938, when Emil Gilels won first and Yakov Flier took third place. The scores Michelangeli was giving out were frightening: 10, 6, and even 3 points (“unsatisfactory” and “failure”). From the first stage of the competition he liked only a few performers, and Ashkenazy first of all.

In short, we were surrounded by the cream of the pianistic world, close contact with which had been especially unusual for us, the Soviets. Only one year earlier, the first Western guest artist had come to Moscow after Stalin’s death, Gerhard Puchelt, an average, reliable pianist from Germany. The person next to me in the audience said to her friend, “Isn’t it strange to sit in the Great Hall and listen to a musician from a capitalist country?” as though this were some mysterious creature from another world.

Every participant was given 20 minutes for rehearsing on the stage early in the morning of his performance. I realized suddenly that one out of the two Etudes chosen for my first round later the same day (the particularly difficult A- Minor, No. 2 from Op. 10) wasn’t working: Due to the unusually tight Steinway keyboard, I simply was not able to hold out to the end — and this just after Gilels’ recent compliment that he had not heard such a performance “since Y. Zak’s time”, whose A-Minor Etude happened to be one of the high points of the 1937 competition. I did not allow myself to get upset over this, since the études could be switched with any from the second stage’s program, and that is exactly what I did: the A-flat Major, Op. 10, No. 10.

An hour before the performance the contestant was brought to a distant room with a piano in the Philharmonic building. Simultaneously, the contestant who was to play two numbers before you was brought to the stage for a half-hour performance. You were alone, no one around. You could play, read, lie down on the sofa, or climb the walls.

In half an hour they came for you and accompanied you to the dressing room which had just been vacated by the preceding contestant. I turned a knob on the wall, heard over a radio the live breathing of the huge audience in the hall, and turned it off even quicker.

There was a big bottle of Valerian tincture (a popular European sedative) on a table; we were told it was emptied by the end of each day. I walked around the room a little, then warmed up at the piano to avoid being alone with my thoughts and the nervousness of waiting. Since then I have never arrived at my concerts too early. At last the door opened. “Pan Paperno . . .”, and I was led to the stage. My impression was of a huge, overcrowded hall, polite applause, six pianos on the stage, wires and microphones everywhere.

My playing was not bad, maybe even good, it just was not me playing.

There are no excuses in our profession, even though I definitely had some reasonable ones. Besides, stage performance entails too much of the irrational to allow oneself to say in advance “this is going to be good today.”

In any event, the applause became warmer with each new piece, and when I was leaving the stage the audience was openly friendly. Next day, there were good reviews in the newspapers. I was able to relax and listen to several who were still to play their first stage.

So far, I’d heard only two favorites — Ashkenazy and the Pole, Adam Harasiewicz. In my opinion, others in the lead group were the very lyrical Fu-Tsung, the somewhat manneristic Frenchman Bernard Ringeissen, the interesting Japanese woman Kioko Tanaka, and our short, rosy Dmitry Sakharov, who won the sympathy of the audience when he got lost on stage between pianos and microphone wires. What was more important, he played his first stage just magnificently.

The meeting of the participants at which we were told the results of the first stage was emotional. The old man Drzewecky said that he was starting, “with a heavy heart,” his recitation of the list of participants who had made it to the second stage. He appealed, in very warm terms, to those who were about to learn that their participation in the competition was over: He urged them not to despair, but to continue to work persistently and perfect themselves in order to come back to Warsaw in five years, for the next competition, with great chances for success, etc.

Strained attention had reached its peak. A good Bulgarian friend of mine, Snezhánka Bárova, whispered: “Mitya, hold me, I’m going to fall down…” Forty of us made it to the second round (fortunately, Snezhanka was among them); about sixty were eliminated. The Competition Committee had generously invited them to stay as guests for several more days and go with the others to visit Chopin’s birthplace in Zhelazóva Vólia, etc.

I had passed into 6th place. Taking into account that Ashkenazy was first, leaving Harasiewicz behind by 1-1/2 points, and that the next five contestants followed one another closely, it was clear that the fight was still ahead. There was a small sensation when Sakharov passed ahead of Fu-Tsung and Ringeissen.

The evening concerts by members of the jury began. Now, I remember only separate pieces from the programs of L. Oborin, L. Kentner, I. Ungar, Y. Zak, F. Guerra and others. Eighty-year-old E. Bosquet played his own transcription of the Mephisto Waltz by Liszt-Busoni.

One evening I was sitting with Ashkenazy getting ready to listen to Michelangeli play the Schumann Concerto. The very first phrase made us prick up our ears and, as the Americans say, “that was it.” One did not want to miss one note of this magic. The music, long familiar, was now filled with a new sense of wisdom and kindness. He communicated the same impression with two Scarlatti Sonatas as encores.

One could not merely say about his playing, “gorgeous sound, impeccable technique, touch, etc.” Everything was brought to an almost unbelievable perfection. But even that was not the main thing. Later, when Moscow musicians asked us what had moved us in Michelangeli’s playing we could not find the right words. “Humanity” would be, perhaps, the closest, but it does not get specific enough unless you listened to this amazing musician yourself. We went backstage afterwards to express our delight and gratitude for his Schumann, only to be told by Michelangeli, “You haven’t heard Lipatti!”

Incidentally, this Michelangeli performance was the first one he gave after a two-year break during which doctors were saving him from a galloping consumption or some other illness rare for our times (even the ailments he chose were strange ones…).

There was another meeting with him in the hotel’s corridor several days later. “What do you think about the 4th Rachmaninov Concerto?” he asked V. Ashkenazy and myself. I do not recall what Vova answered. As for me, at the time I took great interest in this music and said so, to his obvious pleasure. Only several years later, when his amazing recording of the 4th Concerto became available in Moscow, did I recall this conversation.

Meanwhile, the second stage of the competition had started and the duration of our programs was extended to 45 minutes — one of the two sonatas (or a ballade and a scherzo), the mandatory piece — Prelude in C-sharp Minor, Op. 45, 3 mazurkas, and 2 études. Only during the morning stage rehearsal on the day of performance did I somehow quickly accommodate myself to the Steinway and get rid of the lingering anxiety about the dangerous étude. Much later, I discovered in N.K. Medtner’s aphorisms: “Do not try to tame a Steinway! Every accent or temperamental hit makes this rough animal wildly refractory. The more indifference, the better this brute works.”

I managed to get rid of my nervousness right away and played the diverse program quite well. A very friendly reaction from the audience as soon as I arrived on stage, and the warm and long applause after every piece, helped me relax and give a free and bright performance. This success increased toward the end, and after the 4th Ballade the audience did not break up for several minutes more, in spite of its being time for intermission. Excited, L. Oborin said in the hotel, “Oh, if you had only played like this at the first stage.” It was a pleasure to learn that Michelangeli had given me 23 points.

Next day, March 10th, was A.B. Goldenweiser’s 80th birthday and I was glad to send him a telegram with the good news. I did not go to my seat at the Hall for the second half of the audition, even though Ringeissen was playing — I simply could not take more music that day. The Frenchman, apparently had also consolidated his position. The next day the popular critic, Jerzy Broszkiewicz, inserted an article “History and Geography” in Tribuna Ludu in which he compared and praised us generously.

As a result of my second round I found myself in 4th place. This did not have practical meaning, however, because starting from second place the participants were separated only by tenths, sometimes even hundredths of a point. Two first-stage favorites — Sákharov and Tanaka — did not endure the tensions of the struggle and rolled back to the end of the first ten. Subsequent dramatic events finally established our places, but had the competition lasted one more round, the results might have been different again — so terribly close we stood in the score table.

Thus the situation became very tense. Before this competition, a Polish contestant had shared the 1st place only once: in the previous contest, 1949, Galina Cherny-Stefanska with Bella Davidovich, and in many respects this decision had been dictated by political reasons. Now, in 1955, the contest organizers felt themselves more independent and passionately wanted to see their countryman as an individual winner at last.

This goal could only be reached through Adam Harasiewicz, who so far had obviously not kept up with Ashkenazy in the struggle for first prize. And here, because of subsequent events, one can consider the story which was spread unofficially about the end of the competition. Some believed that there was an agreement between the Polish and French factions on the jury to give mutual support to each of their favorites. One can well understand that the Polish stake was highest — 1st prize.

By the time of the third stage, not only had jury member Marguerite Long of France arrived, but also an honorary guest, Queen Elizabeth of Belgium. From that point onwards, all concerts were to be held in the evenings with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra. The men were to play in tailcoats. As far as I remember, it was only for the three Soviet participants, Ashkenazy, Sakharov, and myself (totally lacking any such experience) that the jury made a reluctant exception.

People would stop us on the street, asking for help in obtaining tickets. Meanwhile the long strain began to take its toll. Even Ashkenazy had begun to complain that some spot in an étude was repeatedly going out of his control. I became afraid of a relatively simple passage in the 1st movement of the 2nd Concerto. In short, once Ashkenazy had performed his concerto with a little less confidence, it unexpectedly poured oil on the flame of the fight for first place. When Harasiewicz’s turn came, a couple of days later, agitation reached its peak. It was hard to make one’s way into the packed hall. The journalists, movie and TV cameramen scurried back and forth with their bulky equipment. All this unaccustomed racket and excitement became one more irritant for some of us (and you may guess who was one of these…).

This time it was Adam who turned out to be up to the mark. The third stage was his moment in the sun. Living up to the audience’s expectations, he ignited a burst of patriotic rapture in the hall. Of course, under any circumstances he could not pass Ashkenazy in the total sum of points received for all three stages, but at that time there was much we did not know.

As for me, I had the same experience I had gone through previously during my first elimination trials in Moscow in 1949 — I simply do not remember how I played the first movement of the Concerto. When I came to myself it was behind me. The second and third movements satisfied even me. The Conductor, Bógdan Wodíczko, embraced me on stage, to the audience’s delight. But this was a competition, after all, not a concert…

I still remember the next day’s review by the same J. Broszkiewicz. After mentioning the “charming tone” in the slow movement, and “brilliant technique” and “lively rhythm of the mazurka in the 3rd movement,” he added, not without some humor, “But, as we know, there are three movements in the Chopin Concerto.”

Another Soviet participant, Naum Starkman, who had been placed in the second five, performed very successfully.

In this highly uncertain situation, in order to help ease our tensions while awaiting the final jury’s decision, the competition committee gathered all the participants in the hotel restaurant after the last audition. There was much wine, sincere talk, anticipation of parting. The twenty of us who had just gone through this severe ordeal were trying not to think about what was going on in the jury room.

After midnight, a gloomy and dismal looking Michelangeli suddenly appeared, taking his seat at a remote table with a glass of wine and the inevitable cigarette. Much later, about 2:00 AM, the rest of the jury began to emerge. Our two judges, Oborin and Zak, looked very displeased and agitated. One could understand why: the first prize had been awarded to Harasiewicz. Ashkenazy was in second place. Everyone felt the unfairness of this decision. Michelangeli, in protest, would not sign the document recording the competition proceedings (that is why he had emerged earlier), but the business was done.

The two winners were followed by: Fu-Tsung, 3rd place; B. Ringeissen, 4th; N. Starkman, 5th; and me, 6th, behind by a few hundredths of a point. Two Poles, L. Grihtolówna, and A. Tchaikovsky (who died in 1982), D. Sakharov, and K. Tanaka completed the list of the first 10 winners. The second ten received honorary diplomas. Among those later to become popular were Peter Frankl, Tamas T. Vasari, and our own Nina Lelchuk.

Two days later, the ten brand-new laureates performed at the gala concert that closed the competition. The honor of concluding this special evening fell to me, because we were assigned to play in the following order: 1st prize, then 10th, 2nd prize, then 9th, 3-8, 4-7, 5-6.

The entire audience, including Queen Elizabeth, the Polish government, and all the various diplomatic corps, stayed in their seats until well past midnight when the concert finally ended. Feeling unfettered after our long ordeal, we enjoyed playing, and the audience asked for encores.

With this as background, the setback that occurred to Harasiewicz was especially unfortunate. While playing the 23rd Etude in A minor, Adam experienced difficulties, even having to stop for a moment. This derangement now seems symbolic, to some degree, of his subsequent concert career. The constant burden and responsibility of his position as a winner turned out to be beyond his strength. He developed a fear of the stage and not long after all this, his name began to appear more often on record jackets than on concert bills, even though the most prestigious concert halls were always open to the winner of the Chopin competition.

Next night, the then-President of Poland, B. Berut, had arranged a large reception celebrating the official closing of the competition. Several hundred guests, Polish musicians, actors, journalists, diplomats, etc., packed the halls where huge tables were crammed with delicate dishes and beverages. Many soon reached a high level of rejoicing and roamed around, searching for the next drinking companion. Nothing shocked anybody, in spite of the presence of the Queen, who radiated a sincere good will and simplicity to all around her.

After this official ending, all the participants who remained in Poland were entertained with a trip to ancient Krakow — one of Europe’s most beautiful cities. There Michelangeli repeated his Warsaw recital program, although his temperature had risen and the concert had to be delayed one hour. Again, as in Warsaw, the audience experienced a feeling of witchcraft. After the concert there was an ovation that did not quiet down for about 15 minutes. Michelangeli took few curtain calls, and bowed without smiling. He was displeased with the old piano and seemingly by the fact that he had allowed himself to be persuaded to play at all. For several years almost every performance he gave, especially during his American tours, was marked by eccentricity and escapades. Suddenly, responding to the audience, he sat down at the piano and repeated as an encore the Brahms-Paganini “Variations” with the same degree of brilliance and perfection. At this time, L. Oborin finally admitted: “Yes, this young man CAN play the piano,” and from his lips such praise meant a lot.

Finally the time had come to return to Moscow after a month and a half’s absence. All eight of us in the train had mixed feelings of relief and sadness…

In closing my remarks about the 1955 Chopin Competition, I must mention that the style of playing that prevailed forty years ago (and earlier) was considerably faster than it is today. This difference is perhaps most noticeable in the performances of the Mazurka in F-sharp minor and Scherzo in E major toward the end of this recording. I now find most performances from that era, including many of my own (although none of those chosen for this recording — in fact, the E Major Scherzo sounds particularly sincere and spontaneous to me today), almost hectic and difficult to enjoy. In chapter five of my memoirs, I discuss at length the social, historical, and aesthetic trends that have led performers and listeners to favor progressively slower tempos over the last few decades.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:48

Recorded:

Tracks 1 & 2: DePaul University Concert Hall, May 15, 1980

Track 3: WFMT Studio One, January 17, 1989

Track 4: Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago, July 22, 1977

Track 5: WFMT Studio One, November 22, 1983

Tracks 6 – 12: Material under license from The Fryderyk Chopin Society, Warsaw, Poland

Producer: James Ginsburg

Cover: Photo by Erik S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

© 1996 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 026