Store

Store

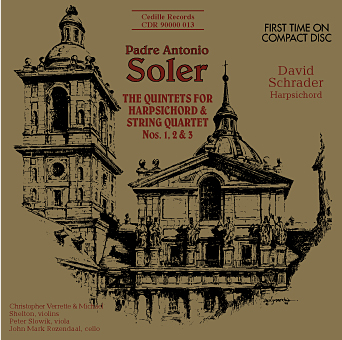

Padre Antonio Soler: Quintets for Harpsichord and Strings Numbers 1-3

David Schrader, Chicago Baroque Ensemble

Captivating and quirky, the quintets for keyboard and strings of Spanish composer Padre Antonio Soler were rare, even in the heyday of LP recordings. Now they are available for the first time on compact disc.

Padre Antonio Soler’s six quintets for harpsichord and string quartet are post-Baroque masterstrokes, blending Baroque and early Classical styles with a savory seasoning of Spanish folk music.

The complete quintets are represented on two CDs, sold separately, and are the only currently available recordings in any format of Soler’s quintets, according to the fall 1996 Schwann Opus catalog, and form the first complete set on CD. (The second three quintets are available on Volume II.)

Cedille undertook the Soler quintets because they represent neglected yet pleasurable repertoire — the label’s hallmark — and in Schrader, Cedille found a Chicago-based artist who championed Soler and could be counted on to give a world-class reading, Ginsburg says.

Though rare even on LP, Soler’s quintets charmed listeners of the vinyl era. American Record Guide (October 1964) deemed the Quintet No. 6, on Westminster Records, “well off the beaten track of repertoire” and of “considerable musical as well as historical value,” with “lovely moments that are worth savoring for themselves.” Reviewing a Vox LP set of the complete quintets, Stereo Review’s Richard Freed wrote (October 1973), “All six of these are really so endearing that it would take a hard heart to resist the set, once exposed to it.” Paul Henry Lang, in High Fidelity (October 1973), called them “charming, melodious, and euphonious compositions.”

Preview Excerpts

PADRE ANTONIO SOLER (1729-1783)

Quintet No. 1 in C Major

Quintet No. 2 in F Major

Quintet No. 3 in G Major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Keyboard Quintets of Soler

Notes by David Schrader

Antonio Francisco Javier Jose Soler y Ramos was baptized on December 3, 1729. Destined for a career in the church, in 1736 he entered the choir school of the great Catalan monastery of Montserrat, where he studied with the monastery’s Maestro, Benito Esteve, and its organist, Benito Valls. After becoming Maestro de Capilla, or Music Director, at Lerida circa 1750, Soler was ordained to the subdiaconate in 1752. He entered the Hieronimite monastery at El Escorial, the large palace and college cum monastery established a century and a half earlier by King Philip II, taking the habit on September 25, 1752. Soler became Maestro de Capilla at El Escorial in 1757, upon the death of the incumbent maestro, the redoubtable Domenico Scarlatti. The monastery’s extant records, or actos capitulares, note that Soler had an excellent command of Latin, organ playing, and musical composition; his conduct and application to his discipline were said to have been exemplary.

Soler is known for his theoretical writings, which, in addition to the famous Llave de le modulacion (key to modulation) of 1762, even include a treatise on the conversion rates between Catalan and Castilian currencies. While the principles contained in the Llave are still recognized as valid, it is well to note that the modulations were considered radical enough in eighteenth century Spain to elicit critical rebuttal, to which Soler himself responded with a 1765 tract entitled Satisfacción a los reparos precisos (reply to specific objections).

Like Domenico Scarlatti, Soler also enjoyed the patronage of a member of the royal family: Prince Gabriel, the son of Charles III. Soler wrote many of his solo keyboard sonatas for the prince, who was also quite likely the inspiration for Soler’s six concerti for two organs and his six quintets for keyboard and strings.

The source for Soler’s quintets for keyboard and string quartet is a manuscript found in the archive for the Maestria de Capilla, or Music Directorship, at the Escorial. It consists of five notebooks, which in turn give us the full scores and the individual string parts for the quintets. The score for the first quintet is inscribed:

Obra primera

Quinteto primera con violinos, viola, violoncelo y organo o clave obligado.

Para la Real camara del Serenissimo Señor Infante Don Gabriel

Compuesta i dedicada a su Alteza Real por el Fray Antonio Soler. Ano 1776.

(First work, first quintet with violins, viola, violoncello and obbligato organ or [other] keyboard. For the royal chamber of the Most Serene Lord Prince Gabriel, composed and dedicated to His Royal Highness by Father Antonio Soler in the year 1776.)

Although Soler is primarily identified with the baroque tradition, his incipient classical bent is well favored in these remarkable quintets. Like many of Soler’s later sonatas for solo keyboard, the quintets are multi-movement pieces. While Soler does not follow the standard sequence of movements employed by Viennese classicists of the time, the character of the music itself is largely reflective of the esthetic of the latter part of the eighteenth century. Although this is not confirmed, scholars believe that Soler had some familiarity with the work of Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805), who lived in Madrid from 1769 to 1785, after having spent his formative years in Vienna in the late 1750’s and 1760’s. This would offer a precedent for the skillful string quartet writing found in Soler’s quintets. The imaginativeness of Soler’s writing often defies contemporary parallels, however, suggesting that Soler may have conceived these quintets with only the most superficial knowledge of classical traditions outside of Spain.

The keyboard parts are composed in a style similar to that of the sonatas for solo keyboard. The cleverness, elegance, and generally mercurial virtuosity of those sonatas are found the quintets as well. The solo line contains many examples of the hand-crossings, rapid passage work, great leaps, and rapidly executed ornamentation that typify Soler’s keyboard style. Although this recording employs a harpsichord, the scores indicate that a chamber organ was also desirable. The organ for which Soler originally composed the quintets seems to have had two keyboards and several different registers, such as regals (buzzy, short-resonator reeds) and the flautado, or principal register.

The first quintet, in C major, has five movements. The opening allegretto is cast in a form reminiscent of a classical concerto. The keyboard part is written to contrast with, rather than support the string parts. It also does not enter until after a generous introduction played by the strings. The key scheme of a typical classical opening movement is observed with one slight alteration: the recapitulation is truncated and in an unexpected key; the tonic key does not reappear until the coda. An andantino in the dominant key of G major follows; in 3/8 time, it has the character of a passepied. The next movement, marked allegretto en fuga, is composed in an imitative style that demonstrates Soler’s excellent command of counterpoint. The movement is far from ponderous, however: its lightness of motion and basically cadential harmony make it essentially similar in character to the other, more galant movements. The minuetto, marked allegretto, is in the relative minor (A minor), with a trio section for strings alone in F major. The concluding allegro is similar to the first movement in that the classical key scheme is not respected: the chief modulation is not to the expected dominant key of G major, but to the supertonic of D. Soler’s delight in writing challenging, lively music is particularly in evidence in this movement: athletic string passages and quick hand-crossings in the keyboard part abound.

The second quintet is in F major and has three movements. The first, a lovely cantabile con moto, is again reminiscent of classical concerto form, with a lengthy introduction by the strings preceding the first entrance of the keyboard. Here the tonic and dominant hierarchy of the classical style is followed in the normal manner. The middle movement is a minuetto, which, like that of the first quintet, is marked allegretto and contains a trio section for strings alone in the relative minor. The finale, marked allegro, is cast in a complex form. The basic form appears to be sonata-allegro, but just as the movement seems about to end, it is interrupted by a portion of music aptly titled “divertimento,” which takes the form of a minuet in several sections. The divertimento ends on a half-cadence, which ushers in a coda that reintroduces the material of the allegro and concludes the piece with a blaze of rapid motion.

The third quintet, in G major, contains five movements, as does the first. Its opening allegretto is also in concerto-type form except that this time, the solo instrument makes an early, five-measure incursion into the opening “tutti.” The largo that follows is particularly splendid. Its gently-moving, sentimental melodies, with their copious ornaments and sighing motives give the impression of something impassioned, but also slightly tongue-in-cheek. For me, it conjures the fanciful image of Lurch, the somber-faced butler of television’s “Addams Family,” falling in love and expressing his feelings at his chosen instrument: the harpsichord. The following allegro pastorile is in the form of a minuet and trio. The minuet section uses the keyboard in an accompanimental manner, while the trio features the keyboard and the strings separately, each body playing its own distinct strain. A graceful andantino grazioso leads directly into the brilliant finale, marked allegro subito.

Throughout the quintets, the writing for both strings and keyboard, though often technically difficult, is supremely idiomatic. The odd-numbered movements make consistent use of the tutti-solo form typical of classical concertos. While the instruments do play together much of the time, the contrast between keyboard and strings is frequently exploited. The final movement of the second quintet displays a formidable mastery of time with regard to the placement and duration of the divertimento. Mozart also used this type of form, most notably in his piano concertos K. 271 (1777) and 482 (1785), each time in the finale. Soler’s classicism is obvious in these works. The date of their composition (1776) and their intrinsic character make the baroque-trained composer’s apparently independent grasp of the trends of the late eighteenth century all the more singular. While working in something of a cultural vacuum, Soler seems to have been aware of the international style that makes music labeled “classical” so easily identifiable as such.

The solo instrument used in this recording is a harpsichord with two keyboards built by Lawrence G. Eckstein of West Lafayette, Indiana in 1975. It is based on the 1745 Hemsch harpsichord housed in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In keeping with eighteenth century traditions, ornamentation has been added where it seems wanted, and certain trills, turns, and such like have been added or deleted, where appropriate, to produce the best musical results. The tuning of the harpsichord is a modified version of the unequal temperament associated with Thomas Young (c. 1800).

— David Schrader

Album Details

Total Time: 68:26

Recorded: Oct. & Dec. 1992 at St. Lukes Church, Evanston, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Facade of the Basilica at El Escorial. Ink drawing by Jack Simmerling.

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: David Schrader

© 1993 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 013