Store

Store

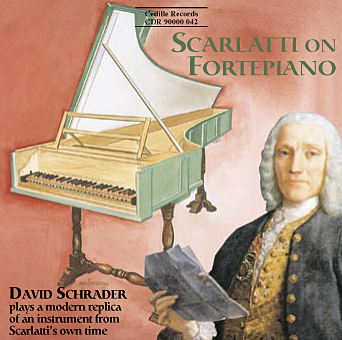

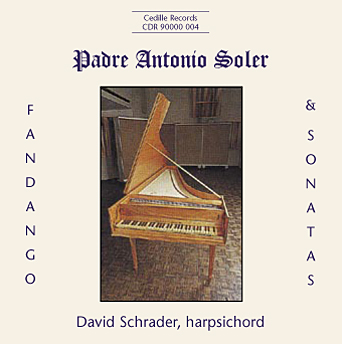

Padre Antonio Soler: Fandango & Sonatas

Keyboard artist David Schrader, a favorite of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, made his solo recording debut with this CD of harpsichord works by Spanish composer Padre Antonio Soler.

Soler’s compositions embrace Spanish folk melodies, show a fondness for syncopations, and require virtuosity from the performer. Soler’s work bridges late Baroque and early Classical styles.

“Like his illustrious predecessor at the Spanish court, Domenico Scarlatti,” writes David Schrader in his program notes,”Soler also enjoyed the patronage of a member of the royal family . . . While Scarlatti’s influence on Soler is evident, it is well to note some salient differences in the two composers’ works for keyboard. Soler composed more sonatas in a relatively moderate tempo than did Scarlatti; the acciaccaturas (dissonant notes played quickly in between harmonic tones) so germane to Scarlatti’s style rarely appear in Soler’s works; and Soler made frequent use of Alberti bass patterns, which Scarlatti avoided. Similarities, however, include the demand for virtuosic technique, a fondness for syncopations, and a thorough infusion of Spanish folk music.”

The instrument used in the recording (an 8-foot single-manual harpsichord) was built by Paul Y. Irvin of Glenview, Illinois in 1989. It has a five-octave range, two sets of unison string, and a buff stop. Its design was inspired by the sound and acoustical design of a small 1681 Giusti harpsichord now in the Germanisches Museum, Nürnberg.

Preview Excerpts

PADRE ANTONIO SOLER (1729-1783)

Sonata No. 60 in C major

Sonata No. 63 in F major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Keyboard Music of Soler

Notes by David Schrader

Although Padre Antonio Soler composed numerous works for the church and other venues, he is best known for his keyboard sonatas. These highly varied works occupy a central position in Soler’s total output and represent a unique contribution to the repertoire for harpsichord, organ, and fortepiano.

Antonio Francisco Javier Jose Soler y Ramos was baptized on December 3, 1729. Destined for a career in the church, in 1736 he entered the choir school of the great Catalan monastery of Montserrat, where he studied with the monastery’s “Maestro,” Benito Esteve, and its organist, Benito Valls. After becoming maestro de capilla at Lérida circa 1750, Soler was ordained to the subdiaconate in 1752. He entered the Hieronimite monastery at El Escorial, the large palace and college cum monastery established a century and a half earlier by King Philip II, taking the habit on September 25, 1752 and making his life profession as a monk on September 29, 1753. Soler became maestro de capilla at El Escorial in 1757, upon the death of the incumbent maestro. The monastery’s extant records, or actos capitulares, note that Soler had an excellent command of Latin, organ playing, and musical composition, and that his conduct and application to his discipline were exemplary.

Soler is known for his theoretical writings, which, in addition to the famous Llave de le modulación (key to modulation) of 1762, even include a treatise on the conversion rates between Catalan and Castilian currencies. While the principles contained in the Llave are still recognized as valid, it is well to note that the modulations were considered radical enough in eighteenth century Spain to elicit critical rebuttal to which 4 Soler responded with a 1765 tract entitled Satisfacción a los reparos precisos (reply to specific objections).

Like his illustrious predecessor at the Spanish court, Domenico Scarlatti, Soler also enjoyed the patronage of a member of the royal family, Prince Gabriel, the son of Charles III. Soler wrote many of his sonatas for the prince, who also inspired Soler’s Six Concerti for Two Organs and his quintets for keyboard and strings. While Scarlatti’s influence on Soler is evident, it is well to note some salient differences in the two composers’ works for keyboard. Soler composed more sonatas in a relatively moderate tempo than did Scarlatti; the acciaccaturas (dissonant notes played quickly in between harmonic tones) so germane to Scarlatti’s style rarely appear in Soler’s works; and Soler made frequent use of Alberti bass patterns, which Scarlatti avoided. Similarities, however, include the demand for vituosic technique, a fondness for syncopations, and a thorough infusion of Spanish folk music.

Soler’s music spans two eras. Born into the latter part of the baroque period, Soler lived to compose music reflective of a later tradition. The pieces on this recording range from the one-movement sonatas that figure forth the work of Scarlatti to two and three-movement sonatas written in a more classical style.

The Fandango is a dance of courtship that originated in Andalusia (the southern part of Spain) in the early eighteenth century. It had become popular with the aristocracy by the middle of the century and was represented by composers other than Soler, most notably Luigi Boccherini, who included a fandango in one of his string quintets. The dance is of a passionate character, to say the least, and was known to raise just enough prurient eyebrows to be attractively naughty to its hearers. Soler’s Fandango is constructed 5 over a constant harmonic pattern (I call it an example of eighteenth century minimalism) and increases in intensity and velocity toward the end. It is remarkable that the composer managed to sustain such energy and interest over 450 measures of music. The virtuosity and imagination ever present in this fandango — handcrossings, trills, syncopations, all that can be brought forth on the keyboard — is combined with Spanish folk music to produce a truly sizzling dance.

The sonatas in G major, C major, Eflat major, and the two in D minor (the second of which is Soler’s “dorian mode” sonata) reflect the esthetic of the late baroque, as well as some of Scarlatti’s influence. At the same time, however, the regularity of Soler’s phrasing, as well as other differences in keyboard styles previously noted, demonstrate the independence of Soler’s musical thoughts from those of Scarlatti. Still, the love of diabolical hand crossings, such as those found in the early C major sonata; the tender lyricism of the E-flat sonata; and the passionate drive of the D minor sonatas show that Soler and Scarlatti did share something of a common heritage.

In the two and three movement sonatas from the classical period, the binary structure of the preceding pieces is transformed into a nascent sonataallegro form. Also present in these works is the characteristic harmonic tension and logic that identifies the music of the late eighteenth century as well as an intense rhythmic drive that can, upon occasion, suggest scores of hungry cats being summoned to the feeding trough (e.g., second movement of the F major sonata). While the “baroque” sonatas also have a strong motoric rhythm, the more cadential harmony of those pieces makes their rhythm seem more integral to their intent. In the classical works, on the other hand, the rhythm acts as a rigorous background for the struggle between larger harmonic areas (e.g., tonic vs. dominant). The sonata in F 6 major, however, includes a reactionary twist: its third movement is an intento, or fugue, whose marvelously intricate counterpoint suddenly gives way to a thoroughly classical, seven-bar, quasioperatic coda!

The changes in accidentals that occur periodically throughout the disc and the embellishments not already added by the composer are supplied by the performer in accordance with performance practice applicable to the style of eighteenth century Spanish music. All repeats are observed except for those in the E-flat major sonata (No. 16). Repeated passages tend to be more embellished the second time through. The harpsichord was tuned to A=415.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:51

Recorded: Sept 8 & 9, 1990 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover: The harpsichord used on this recording. Photo by Andrew Halpern

Notes: David Schrader

© 1991 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 004