Store

Store

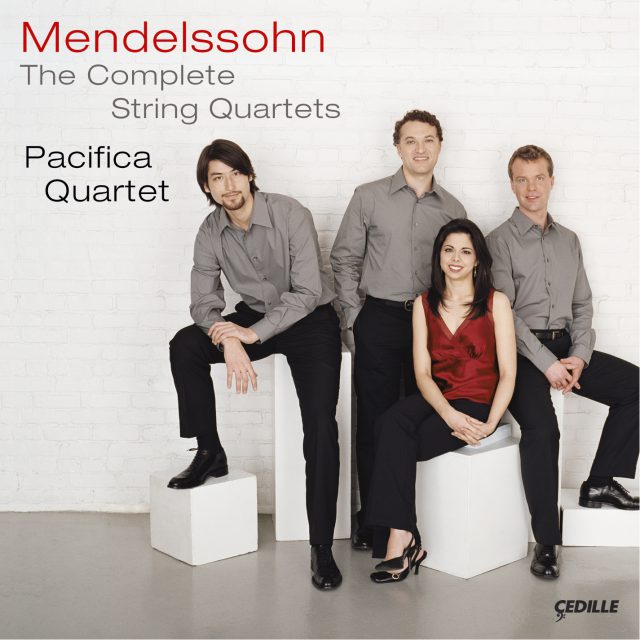

Mendelssohn: The Complete String Quartets

One of today’s most dynamic and exciting ensembles, the Pacifica Quartet celebrates its 10th anniversary with a three-CD set of Mendelssohn’s complete string quartet cycle. Known for its “stunningly expressive performances” (The Guardian) and “ideal balance” (Washington Post), the youthful Pacifica is a perfect match for this early Romantic composer’s exuberant chamber music.

Preview Excerpts

String Quartet in E-Flat Major

String Quartet in E-Flat Major, Op. 12

String Quartet in F Minor, Op. 80

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletMendelssohn: The Complete String Quartets

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The famous sign on the road to the Marlboro Music Festival warns, “Caution: Musicians at play.” Marlboro was originally dedicated entirely to the performance of chamber music as a form of artistic relaxation, providing rewards different from those of orchestral or solo performances. Chamber music offers the opportunity for one instrumental voice to sound on its own, and the sense of engaging in a musical conversation with just a few colleagues. There’s also the close musical encounter with the mind of a particular composer, and a chance for musicians to challenge their abilities in a very exhilarating way.

Chamber music was originally an amateur musical occupation, but as the 18th century became the 19th and music of all types became more complex, the string quartet in particular evolved into a genre reserved for skilled professionals performing before an audience. This situation could be perceived as an active-passive division of responsibility: the musicians play, the listeners sit back and enjoy. If all they do is sit back, however, they’re missing a great opportunity. Chamber music offers an invitation to sit up, not back; to sharpen your ears, extend your musical antennae, and become involved in what’s going on. Following the progress of a theme through various voices, listening to its transformations and its returns, is quite a different proposition when you’re faced with four players instead of dozens of symphony musicians. You can appreciate the slightest variation in tone color, hear the tiniest variation between a theme’s initial statement and its recapitulation. Even without the score, even without knowing the intricacies of formal procedures, you can hear with the greatest clarity the progression from opening statement through key changes and development to the final restatement that brings the music to a satisfying resolution. And when you are listening to a string quartet, you are often listening to a composer’s highest effort, his contribution to a rarified realm, but one that offers enjoyment for everyone involved.

The great composers of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the great chamber-music practitioners of the modern era, laid the groundwork for this profound sense of satisfaction through the manipulation of form, but not in any dry academic sense. Sonata, variation, and fugue are not intended as blueprints: they are procedures that have evolved over time to allow a composer and his interpreters to work out the musical materials into a shape that becomes both technically and emotionally satisfying.

In his 16 string quartets, Beethoven moved from the conventions of the Classical era to the dramatic, dynamic tensions and emotional storms of his late works. Reacting to those late works, and to the emphasis on melody and personal expressiveness that characterized the Romantic era, Felix Mendelssohn crafted a group of string quartets on a smaller scale than Beethoven’s: fewer works, generally shorter in length, exhibiting a less extreme emotional range. Yet his achievement in the quartet realm is not of lesser quality, even though it is somewhat less familiar.

In the autumn of 1825, a few months shy of his 17th birthday, Mendelssohn completed his String Octet in E-flat, generally acknowledged as one of his most accomplished and inspired masterpieces, and as one of the pinnacles of Western string chamber music. To a considerable extent, his other chamber music has been overshadowed by the Octet, an unfair circumstance that precludes a well-rounded understanding of his output as a whole. Mendelssohn’s chamber-music list includes a wide variety of pieces: the Octet, three piano quartets, various sonatas and shorter pieces for violin or cello with piano, two string quintets, two piano trios, a sextet with piano, seven completed string quartets, and four unrelated individual movements for quartet that are often played in combination as a kind of supplemental work.

The chronology is as follows:

1823: String Quartet in E-flat (published posthumously)

[1825 Octet]

1827 String Quartet in A Minor, Op. 13

1827 Fugue in E-flat [Op. 81/4]

1829 String Quartet in E-flat, Op. 12

1837 String Quartet in E Minor, Op. 44/2

1838 String Quartet in E-flat, Op. 44/3

1838 String Quartet in D, Op. 44/1 [Op. 44 published as a set in 1839]

1843 Capriccio in E Minor [Op. 81/3]

1847 String Quartet in F Minor, Op. 80

1847 Andante in E [Op. 81/1]

1847 Scherzo in A Minor [Op. 81/2]

The artificially-created Op. 81 was published posthumously.

Like Mozart and Schubert, Mendelssohn compressed a tremendous amount of creativity into relatively few years; “early,” “middle,” and “late” styles are not terribly useful concepts when considering composers who didn’t survive past their thirties. Yet stylistic evolution is evident in the music of all three of these child prodigies, whose skill and understanding grew and changed within their short lives. Early, middle, and late divisions are more easily and commonly made in studying the works of Beethoven, who made it into his middle fifties (a reasonable life span for the early 19th century), and whose music quite clearly falls into three distinct stylistic groups. Each of these Beethovenian “periods” can be characterized by his three groups of string quartets: the Op. 18 set that confronts and builds upon the achievements of Haydn and Mozart; the five lengthier and more complicated quartets of 1806–1810; and the five astonishing late works that completely redefined what a string quartet could be.

As with Beethoven, Mendelssohn’s quartets also come in three distinct groupings:

Early E-flat Quartet, Op. 12, and Op. 13 — These works find a youthful composer appraising, confronting, and partially transcending the traditions of his predecessors: Haydn and Mozart in the first instance, Beethoven in the case of Opp. 12–13, works that take specific Beethoven quartets as points of departure.

Op. 44 Nos. 1–3 — These are “middle” in terms of our parallel; Mendelssohn has developed the individual quartet voice he found in Opp. 12–13, now forging a true Classical-Romantic union of satisfying formal structures and expressive melody.

Op. 80 — Grief dominates this late work written almost literally under the shadow of death. Mendelssohn’s always-fragile health had been failing for some time by 1847, due at least in part to overwork and constant wearisome traveling, but it would be impossibly melodramatic to suggest that he foresaw his own imminent demise. At the time of writing the emotionally-wracked F Minor Quartet, the death that loomed over him was that of his beloved older sister, Fanny, who from earliest childhood had closely shared Felix’s love for music, art, and poetry. Mendelssohn had always had happy personal relationships: with his parents, with his wife and their five children, and with his friends. But Fanny had been extra-special; from her loss he never recovered. The F Minor Quartet confronts the anguish of mortality.

Mendelssohn’s 1823 quartet was written very much under the influence of his principal teacher, Carl Zelter, who was granted the opportunity to train a prodigiously gifted boy, already proficient on both piano and violin, in the traditions of past greatness. Zelter emphasized Bachian counterpoint and the instrumental procedures of Haydn and Mozart in his teaching of Mendelssohn, and the early E-flat quartet (not published until the 1870s) reflects these preoccupations. Most striking to our ears is the constant prominence of the first-violin part. This prominence would never entirely go away in Mendelssohn’s quartets, but in this first work the lower parts are quite obviously subjugated. Also of note is the sequence of the movements and their tempos. In all but one of his other quartets, Mendelssohn placed the slow movement third. This early one situates the slow movement as Haydn and Mozart usually did, in second place. It may be a bow to tradition, but it also serves to heighten contrast. The sonata-form first movement is very regular in its layout of two conventionally-patterned themes through exposition, development, and recapitulation. The ensuing Adagio is much more lyrical and chromatic and shifts to the relative C Minor. To follow it, Mendelssohn creates a sprightly Minuet very reminiscent of the 18th century, then proceeds to show off his skill in a double-fugue finale, wherein for the first time we really hear the second violin, viola, and cello as individuals. Fugal finales were characteristic of Haydn’s early quartets, showing once again the young Mendelssohn’s direct inspiration from his predecessors.

It’s rather unusual to talk about a composer’s first two “mature” quartets when they date from his 18th and 20th years, but the quartets Opp. 12 and 13 show Mendelssohn’s individual voice emerging from the years of apprenticeship. Two earlier works had already shown Mendelssohn’s genius in full flower: the Octet and the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The 1820s found Mendelssohn maturing from the child-prodigy era of string symphonies and chamber operas, and from schoolboy to international traveler. They also saw him confronting his grief over the death of Beethoven in 1827, and his musical response to what he regarded as some of the Viennese master’s most significant works, the middle- and late-period string quartets. (His attitude in this regard marked a complete break with Zelter who, in common with many leading musicians of the time, considered Beethoven’s late quartets unplayable.) Beethoven’s influence plays a part in Op. 12 and in Op. 13 — one of Mendelssohn’s most strikingly original chamber works, fully worthy of comparison with the iconic Octet. Both quartets show Mendelssohn’s skill with cyclic form (interconnecting the themes of a work’s different movements). The works are highly contrasted in mood: Op. 12 emphasizes serene good humor while Op. 13 displays a degree of passion and dramatic contrast not always associated with this supremely refined composer.

Mendelssohn completed the E-flat Quartet Op. 12 in London in 1829, during the first of his many journeys to the British Isles. (This first trip would find him exploring England, Wales, and Scotland, in which he found inspiration for two of his better-known works, the “Scottish” Symphony and “Hebrides” Overture.) Op. 12 has an Adagio introduction that recalls the similar introduction to Beethoven’s E-flat “Harp” Quartet (Op. 74). This leads to a main portion interestingly-labeled, “Allegro non tardante” (Lively, and don’t hesitate). Essentially monothematic in its exposition, the first movement presents a secondary minor-mode theme that will return in its coda and also, with structural prominence, in the final movement. The recapitulation varies the main theme with gentle ornamentation. The “Canzonetta” (Little Song) second movement used to be performed on its own, back in the days when it wasn’t considered heresy to play individual movements of longer pieces. The key is G Minor; the folklike main theme is contrasted with a faster-paced, almost scurrying midsection in G Major. This is one of many Mendelssohn quartet movements that have been likened to the magical Scherzo from his incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The quartet’s third movement, in B-flat, is characteristically Mendelssohnian with its rich melodiousness and closely-drawn harmonies. A recitative-like solo for the first violin stands out before the movement’s end, which leads, with only the slightest of pauses, to the abruptly declamatory opening of the finale. This movement starts out unconventionally in C Minor, then modulates to G Minor before the re-introduction of the auxiliary theme from the first movement, a device that enables Mendelssohn to return to the home key of E-flat for a bravura conclusion to a most ingeniously unified work.

Two years before this remarkable achievement, Mendelssohn dealt with Beethoven and cyclic form in an even more dramatic way. He also adopted a technique Schubert employed in his chamber music: using a song motive to generate key themes. Instead of using the song fragment as the basis for just one movement, however, Mendelssohn incorporates it and its variants and expansions throughout almost all of his A Minor Quartet, Op. 13. (Although written earlier, this was published later than Op. 12; hence the confusing opus numbers.) The movement pattern of Op. 13 places the slow movement second, with the light-textured Allegretto “Intermezzo” coming third as a kind of transparent interlude before the intricate, extended finale — the work’s longest movement, which reintegrates many elements from earlier on.

The major Beethoven influence here is Op. 132, also in A Minor. The slow introduction to Op. 13, a parallel device to Beethoven’s opening, introduces the motive from Mendelssohn’s song “Frage” (Question), a charming love lyric published as part of his Op. 9. The three-note motive has a clearly interrogatory sound; the song’s words include these: “Is it true that you wait for me each evening under the arbor, that you ask the moonlight and the stars about me? Is it true, oh tell me.” The motive appears in the slow introduction and in the movement’s passionate main section, marked allegro vivace. Lyricism and drama combine in this highly expressive movement, which is led by the first violin but provides contrapuntal interest in all four parts. There’s a clear recollection of Beethoven, and yet the sound is really not at all Beethovenian. It is Mendelssohn: lyrical melodies, rich harmonies, symmetrical phrases.

The second movement is oddly labeled “Adagio non Lento,” which could be translated as “Slow not Slow.” In this case, Adagio refers more to mood, while “non Lento” denotes pace: the music is intensely felt but should be played deliberately, not slowly. The main theme in F Major, recalling a hymn, is introduced by the first violin, but the other instruments contribute their own contrapuntal variants. The agitated midsection yields to a heartfelt recapitulation of the hymn motive. In the Intermezzo, pizzicato accompaniment punctuates a folklike main theme whose dancing gaiety is contrasted with an agitated, staccato midsection. The finale returns to the emotional realm of the opening movement, an extended sonata-form Presto whose first-violin theme with tremolo accompaniment once again recalls Beethoven’s Op. 132. Motives from the Adagio movement return. At the end, the theme of the original slow introduction comes back, re-emphasizing the quartet’s association with the yearning “Question” of the song.

During the early and middle 1830s Mendelssohn abandoned the string-quartet medium. He was no longer a student experimenting with the musical media of his elders and predecessors; he was now an internationally-famous performer and conductor for whose services cities and kings competed. His orchestral and choral works won him praise and fame. In 1835 he accepted the directorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and turned it into one of Europe’s premier ensembles, establishing high standards of discipline and enriching the repertory: he led the first public performance of Schubert’s Ninth Symphony, reawakened interest in Haydn and Mozart, and encouraged the work of his contemporaries, Schumann especially. In his work with the Gewandhaus he had the help of one of his best friends and most sympathetic artistic collaborators, violinist Ferdinand David, who became concertmaster in Leipzig at the same time Mendelssohn took over the podium. It was for David that he would write the E Minor Violin Concerto in 1842, and it was for David’s chamber-music evenings that he wrote the three strings quartets of Op. 44 in 1837 and 1838. David and his chosen chamber-music colleagues were technical virtuosi and musicians of deep sensitivity and understanding. Their performances of the new works must have been extremely special treats for their small invited audiences of knowledgeable Leipzig music-lovers. When the three quartets were published as a set in 1839, however, they were dedicated not to David but to “His Highness the Royal Prince of Sweden.”

It’s hard to fathom why these quartets are not more often performed. While they certainly make heavy virtuosic demands on all four players, the modern world contains any number of fine quartets who wouldn’t be in the least dismayed by their challenges. And they are utterly delightful to listen to: full of rich melodies, entrancing harmonies, and piquant dynamic contrasts. By this point, Mendelssohn had become an absolute master of Classical forms, employing them so skillfully that the layout of each work is immediately clear to the listener. The sound manages to be dense with interest, yet transparent; the complexities come off simply as delights. All three are laid out in the pattern Mendelssohn had come to prefer, with the slow movement in third place. Two of them are cast in keys Mendelssohn especially favored, E-flat major and E minor, with a bravura D major work to lead off the set. (The actual order of composition was 2, 3, 1.)

The brilliance and exuberance of the D major quartet’s opening Molto Allegro vivace and concluding Presto con brio — each movement almost a perpetuum mobile — are contrasted with an 18th-century-style Minuet for the second movement. The third movement, marked Andante espressivo ma con moto (moderately slow, expressive, but don’t drag it), is characterized by the evanescent pizzicato string playing that appears in so many Mendelssohnian scherzos, but here the pace is slowed to create a gentle, almost retiring, song-without-words. The finale is structured with ingenious counterpoint. The Allegro assai appassionato (Rather lively, passionate) opening of the of the Quartet in E Minor, with its singing main theme over restless lines of accompaniment, has reminded some commentators of the much more familiar opening of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in the same key. In this work, the second movement is a very rapidly-paced Scherzo that again recalls the Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. A soulful Andante leads into a finale whose rhythms are cast in triple meter, not the duple meter that characterized the earlier movements. (Mendelssohn liked to use the contrast of triple meter, often 6/8; throughout the quartets he often varies the pace with triplet figurations in movements cast in 2/4 or 4/4 time.) The quartet Op. 44 No. 3 in E-flat features characteristic 16th-note figures that appear prominently and serve as a kind of thematic link. There’s a great deal of contrapuntal interest throughout the four movements; the emotional heart is the third, marked Adagio non troppo.

“It would be difficult to cite any piece of music which so completely impresses the listener with a sensation of gloomy foreboding, of anguish of mind, and of the most poetic melancholy, as does this masterly and eloquent composition.” Those are the words of composer-conductor Julius Benedict, a longtime friend of Mendelssohn’s, about the String Quartet No. 6 in F Minor, Op. 80, the Adagio third movement of which is subtitled “Requiem for Fanny.” The totally unexpected loss of his older sister, fellow composer, childhood companion, and adult soulmate completely shattered Mendelssohn. For weeks after her death on May 12, 1847, her devastated brother was incapable of any kind of work. Having retreated to Switzerland for both physical and mental recuperation, he wrote the Quartet in July. Agitation, expressed through dissonance and unsteady rhythms, is the keynote of the entire piece outside of the Adagio. The second theme of the first movement, marked Allegro vivace assai (very fast), unfolds over a harsh pedal point in the cello. An uncertain silence follows the exposition, after which the development picks up the highly-charged atmosphere of the opening. Syncopated rhythmic figures characterize the second movement, marked Allegro assai; it would be misleading to call this movement a Scherzo, since there is little joy in it. The Adagio is mostly in the relative A-flat Major, but this normally serene key here produces a feeling of resigned despair, while a sobbing climax leads to the movement’s gradual dying-away. The tremolo passages that lent such restlessness and uncertainty to the first movement return in the concluding Allegro molto. Whereas most of Mendelssohn’s string-quartet movements feature constant and striking contrasts between loud and soft, the finale of the F Minor quartet is to a large degree labeled “forte” or “fortissimo.” Weeping has turned into an outcry against inexorable fate.

Mendelssohn wrote about this time to his friend Karl Klingemann: “Now I must gradually begin to put my life and my work together again, with the awareness that Fanny is no longer there, and it leaves such a bitter taste that I still cannot see my way clearly, or find any peace.” He would have little time for rebuilding his life, however: in October 1847 Mendelssohn suffered a series of increasingly severe strokes. In November, at the age of 38, he died, and was buried next to Fanny in a Berlin churchyard.

The four individual quartet movements that Mendelssohn left unpublished are often performed together as “Op. 81,” but they possibly work better as individual pieces, since they don’t have the logical relations to each other that are so audible in the full-length quartets. In order of composition, these pieces are:

a cleverly worked-out Fugue in E-flat from 1827, the same year as the Op. 13 quartet;

a Capriccio in E Minor from 1843, structured as an introductory Andante followed by yet another fugue, which is based on a four-note motive from the main theme of the Andante;

a Theme and Variations in E Major from 1847, the last of the five variations modulating dramatically to E Minor;

and a Scherzo in A Minor, light-footed and light-hearted, with pizzicato punctuation.

Andrea Lamoreux is music director of WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time CD1: 74:52

Total Time CD2: 59:26

Total Time CD3: 79:23

Producer: Judith Sherman

Engineers: Judith Sherman, Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Photos of Pacifica Quartet: Anthony Parmelee

Recorded: December 2002, October 2003, March 2004 & June 2004 at Pick-Staiger Concert Hall, Evanston, IL

© 2005 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 082