Store

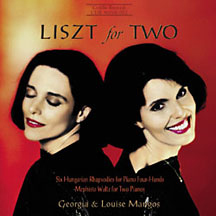

Franz Liszt’s most familiar works — six of his Hungarian Rhapsodies — are best known in their original solo piano versions and Liszt’s orchestrations. Pianists Georgia & Louise Mangos, two “first-rate Lisztians” (Fanfare), perform Liszt’s rarely heard duet versions (one piano, four-hands), possible the only CD ever of the duets. To those who sniff at piano transcriptions as “reductions,” recording producer Jim Ginsburg points out that these Rhapsodies are actually “enlargements” of Liszt’s original solo piano versions.

To round out the program, the Mangos sisters chose Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz for Two Pianos, rather than Liszt’s four-hand arrangement. The Mangos sisters felt the duo-piano version provided “a more glorious score, a more explosive presentation of the musical idea,” making it a better companion for the Rhapsodies.

Rhapsody No. 1 (using the piano duet numbering) must have contained material Liszt deeply loved, for this fourteenth solo rhapsody became the first for orchestra and piano duet, and also formed the basis for his Hungarian Fantasia. No. 2 finds an intermingling of a serious mesto beginning, a wild gypsy central section, and an energetic march. The brilliant No. 3 contains four Hungarian popular songs of Liszt’s time. The heroic No. 4 (the famous No. 2 in the solo and orchestral versions), with its attention-grabbing opening, is the most popular of the Rhapsodies. The introspective No. 5 recalls Chopin themes; many consider it a tribute to Chopin. No. 6, entitled “Carnival at Pest,” is the most compositionally complex and provides “a test of any pair of pianists’ abilities to get around the keyboard without hurting each other,” Henry Fogel writes in the CD notes. For record collectors wanting to compare the duets to piano solo and orchestral performances, the Liszt for Two CD booklet contains a chart showing how the duet numbering corresponds to the other versions.

The Mephisto Waltz No. 1 is quintessential Liszt, treating the division between the beautiful and the diabolic. Based on an episode of the Faust legend, where the Devil interrupts a village wedding celebration to play a macabre tune on a violin, the piece is both menacing and sultry.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

Artists

1: Hungarian Rhapsodies for Piano Four-Hands

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLiszt for Two

Notes by Henry Fogel

When Franz Liszt composed the first of his nineteen Hungarian Rhapsodies (for solo piano) in 1846, he was convinced that he was basing them on authentic Hungarian folk material as played to him by gypsies located in Hungary. The real truth became clear in 1906, when Bart and Kodly published the results of their trips collecting genuine Hungarian folk music. What Liszt actually transformed in his Rhapsodies were commercial, composed Hungarian light music that the gypsies had transformed into their own unique performing style a style we have come to know in its slow-fast alternating dance pattern exemplified by the cs rd s. Between 1846 and 1854, Liszt wrote and published the first fifteen of his Rhapsodies. He returned to the form in his later years, publishing four more in the 1870s.

These Rhapsodies are remarkable for many reasons. They appeal to the visceral in all of us with the athletic demands they place on the performers. At the same time, they speak to the sensual side of our nature with their exceptional melodic invention, unique harmonic language, and shimmering colors. The Rhapsodies are marked by their variety of moods, within each work, and from piece to piece in the set. They are virtuoso showpieces; music that cannot succeed if the performer lacks flair. But flair and technique alone will not suffice. An understanding of keyboard color and (always with Liszt) its relationship to orchestral color is key in performing these works, as is an understanding of the architecture of each one. What ultimately distinguishes these pieces is their uniquely successful balance of keyboard wizardry and lyrical beauty, and the variety and depth of their musical thoughts.

Liszt must have been particularly fond of six of the original fifteen, because he treated them differently from the others. In addition to the solo piano editions, he made for these not one but two other versions: orchestral, and piano duo (one piano, four-hands). It is not known whether he composed the piano duet versions simultaneously with the better-known one-pianist originals, or somewhat later. We do know that Liszt performed these versions with students in his later years, but there is no documentation about when they were made, or why. Since Liszt changed numbering around, and in some cases transposed keys, a chart might be useful:

No. 1 (using the piano duet numbering) must have contained material Liszt deeply loved, for not only did this fourteenth solo Rhapsody become the first for orchestra and piano duet, but Liszt re-worked its material for piano and orchestra in his Hungarian Fantasia. The Rhapsody is dedicated to Hans von Bow, Liszt’s son-in-law at this time (later to be replaced in that role by Wagner to whose music Liszt felt very close, and whose influence can be felt particularly in the piece’s slower sections.) No. 2, dedicated to the great Hungarian violinist Josef Joachim, seems more complex than many of the Rhapsodies with its intermingling of a very serious mesto beginning, a wild gypsy central section, and an energetic march. No. 3 dedicated to Count Antal Apponyi, is actually a setting of four Hungarian popular songs from Liszt’s time, and is one of the most overtly brilliant of the Rhapsodies. In its solo version, the pianist’s ability to traverse its flying octaves with evenness of tone and touch has long been seen as a test of technical accomplishment. The octaves still fly in the duo version, and if the performance is successful it is impossible to tell where one pianist begins and the other leaves off.

No. 4 is the most famous of all; the second of the solo piano Rhapsodies, it is dedicated to the great Hungarian patriot statesman and friend of Liszt, Count Laszlo Teleky. The exceedingly dramatic beginning, perhaps reflecting Liszt’s feelings about the heroic nature of the dedicatee, probably helps account for the work’s popularity. As attention-getting an opening as exists in music, the piece moves from bold opening to a soulful section that recalls a gypsy violin, a more upbeat portion reminiscent of a cimbalom, and a brilliant finale that pulls out all the pianistic stops. No. 5 is the only one of the six to keep both its original number and key. Although dedicated to Countess Szidia Revicsky, many consider this work a tribute to Chopin, who died in 1849. That may explain the unusual nature of this Rhapsody, certainly the most introspective of all. It is titled Hoide-iaque, and some of its material recalls Chopin themes. The sixth and last is dedicated to Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst, an important Hungaran i violinist and composer. Ernst wrote a set of Hungarian Airs, and Liszt wanted to honor him for his service to Hungarian music. Thus, this is the longest of Liszt’s Rhapsodies, and the one that veers farthest from its folk-like origins into major compositional complexities.

The virtuosity and range of color in this last Rhapsody, titled Carnival at Pest, is a test of any pair of pianists’ abilities to get around the keyboard without hurting each other!

Like the Hungarian Rhapsodies, the Mephisto Waltz No.1 exists in versions for solo piano, piano duo, and orchestra. The solo piano version probably came first (1858-59), but it is not known with certainty whether Liszt worked on the other versions simultaneously or subsequently. Liszt appended to the score an excerpt from Lenau’s Faust poem, in which the Devil interrupts a village wedding (with Faust looking on), appropriating a musician’s violin to play his own macabre music. This score demonstrates to us the division between the beautiful and the diabolic that is at the center of much of Liszt’s music (A Faust Symphony, for instance); it is a fascinating blend of the menacing and the sultry. The challenge to performers is that they must show us both extremes while unifying the various elements into a coherent whole.

Album Details

Total Time: 71:25

Recorded: March 22, 23, 25, and Sept. 10, 1999

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover Photography: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Henry Fogel

© 2000 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 052