Store

Store

L’Amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover)

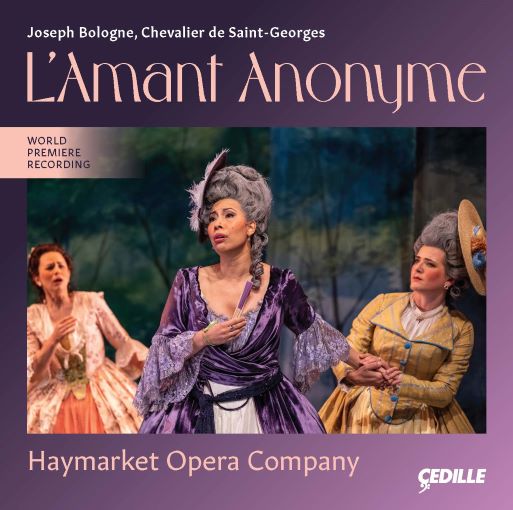

Haymarket Opera Company, Craig Trompeter, Nicole Cabell

Geoffrey Agpalo, David Govertsen, Erica Schuller, Michael St. Peter, Nathalie Colas

Haymarket Opera, Chicago’s premier early opera company that presents historically informed performances played on 18th-century classical era instruments, performs on this world-premiere recording of L’Amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover) by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799).

Premiered in 1780, L’Amant Anonyme was the most successful of Bologne’s six operas and is the only one to survive to the present day. Based on a play by the composer’s patroness Félicité de Genlis, who was a respected writer of the era, the work is an opéra comique in two acts composed in the then-popular style that mixed sung parts with spoken dialogue.

The stellar cast is headlined by 2005 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World soprano Nicole Cabell in the lead role of Léontine, opposite Chicago-native tenor Geoffrey Agpalo as her secret admirer Valcour. The cast also includes David Govertsen (Ophémon), Erica Schuller (Jeannette), Michael St. Peter (Colin), and Nathalie Colas (Dorothée). Company founder and artistic director Craig Trompeter leads the performance, conducting a 19-member contingent of the period-instrument Haymarket Opera Orchestra.

Following Haymarket Opera Company’s live performances of L’Amant Anonyme, the Chicago Tribune wrote, “Haymarket gave as delightful a production of this neglected bonbon as one could imagine,” and praised Cabell’s “expertly, convincingly shaded … radiant soprano” and Agpalo’s “hall-filling, bel canto sensibility … his tenor plush, fluid, and lip-smackingly sweet.” Chicago Classical Review wrote, “Anonymous Lover carried a contemporary freshness and energy born of the caring ministrations of a strong ensemble of period instrumentalists, singers and dancers.”

Composer Joseph Bologne, also known as the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, was among the 18th century’s most extraordinary musical figures. He rose to fame among the European aristocracy as a virtuoso violinist, composer, and conductor; and was noted as one of the greatest swordsmen of his day and led numerous military campaigns as a high-ranking officer. Bologne was born in Guadeloupe to George Bologne, his Caucasian French father, and Nanon, his enslaved African mother. When his father was unjustly accused of murder, the family fled to France to avoid the younger Bologne being sold into slavery.

The CD’s accompanying booklet essay, titled “Silenced No More: Composer Joseph Bologne and the French Operatic Tradition” by Marc Clague, Professor of Musicology and Associate Dean at The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, provides historical context and insight into Bologne’s life and the opera.

L’Amant Anonyme was recorded by the Grammy Award-winning team of producer James Ginsburg and engineer Bill Maylone.

The opera is presented on three CDs at a 2-CD price: the first two CDs contain Acts 1 and 2 complete, with all the French dialogue. A bonus CD 3 contains just the 21 musical numbers. Production photos and full libretto in original French and English translation are included in the CD booklet.

L’Amant Anonyme is the first album to be funded in part by donations to the recently launched Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fund for Vocal Recordings at Cedille Records, created to honor the late Justice’s passion for opera and vocal music in general.

This recording is made possible by the generous support of Patricia A. Kenney and Gregory J. O’Leary and is also supported by Patricia and Jerry Fuller and the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fund for Vocal Recordings at Cedille Records.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Nicole Cabell and Craig Trompeter

on Cedille’s Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Act 1

Artists

1: Haymarket Opera Company; Craig Trompeter (conductor)

2: Geoffrey Agpalo (tenor)

4: David Govertsen (bass-baritone); Geoffrey Agpalo (tenor)

6: Nicole Cabell (soprano)

8: Geoffrey Agpalo (tenor); David Govertsen (bass-baritone); Erica Schuller (soprano); Michael St. Peter (tenor); Nathalie Colas (soprano)

9: Haymarket Opera Company; Craig Trompeter (conductor)

10: Geoffrey Agpalo (tenor); David Govertsen (bass-baritone); Erica Schuller (soprano); Michael St. Peter (tenor); Nathalie Colas (soprano)

12: Haymarket Opera Company; Craig Trompeter (conductor)

14: Nicole Cabell (soprano); Geoffrey Agpalo (tenor); David Govertsen (bass-baritone); Erica Schuller (soprano); Michael St. Peter (tenor)

Program Notes

Download Album BookletGeneral Director & Creative Producer, Haymarket Opera Company

Notes by Chase Hopkins

Joseph Bologne was a champion swordsman, virtuosic violinist,

and successful composer celebrated throughout the 18th century.

His identity as one of a small number of biracial early composers is

significant in the history of western music. At Haymarket, we delight

in discovering “new” things from the 17th and 18th centuries. L’Amant

Anonyme is the only extant opera of Joseph Bologne and in true

Haymarket style, this work has been lovingly restored through the

lens of historical performance. A star-studded cast of artists bring

the charming characters to life alongside our period orchestra

playing rarely heard late 18th-century instruments. A modern score

has been carefully prepared especially for this recording taking

hints and clues left in the only extant manuscript of the work. Our

approach celebrates the fashions and theatrical conventions of

18th-century France in all its beauty, complete with stylish ballets,

gorgeous music for the cast and orchestra, and dialogue. From

Bologne’s heartwarming tale in which love prevails, we believe the

themes of patience, empathy, and devotion will resonate with today’s

audiences and inspire a rich dialogue around issues of equity,

diversity, and inclusion in classical music. Despite his prodigious

talents and extraordinary accomplishments, racism limited the

opportunities available to composer Joseph Bologne in his own time,

and precluded his legacy in ours. Through this recording we are

thrilled to partner with Grammy Award-winning record label Cedille

Records to celebrate the remarkable life and work of Joseph Bologne

with this first-ever recording of his opera, L’Amant Anonyme.

-Chase Hopkins

General Director & Creative Producer

Haymarket Opera Company

Silenced No More: Composer Joseph Bologne and the French Operatic Tradition

Notes by Marc Clague

The music of the Afro-French composer Joseph Bologne, also known as Le

Chevalier de Saint-Georges, is today enjoying a well-deserved renaissance. Well over 200 compositions are credited to the composer — including at least six operas, two symphonies, 14 violin concertos, 14 sonatas, and 18 string quartets, plus more than 100 songs. Yet this prolific output only begins to encompass his impact on the Parisian music scene. He was also, for example, an important musical administrator and conductor. He commissioned Joseph Haydn’s six Paris Symphonies, leading their premieres in 1786 with his own orchestra, Le Concert de la Loge Olympique. All of this raises the question of why Bologne is so little known, at least until recently?

Calls for cultural justice have finally brought overdue attention to the music

of the fashionable Chevalier, but it is the composer’s expressive and skillful handling of melody, harmony, and rhythm that have sparked his successful “rediscovery.” Often called the “The Black Mozart,” this nickname tells us less about Bologne than about the surprise of 21st-century listeners when they discover the quality, charm, passion, inventiveness, and sheer effectiveness of his unjustly neglected music. Nevertheless, a comparison of the two composers can be productive (beyond simply noting that they were musical contemporaries). Both were instrumental virtuosos, both were international celebrities, and both shaped the classical era of Western music. Maybe most intriguing, and despite the reputation of the classical style for symmetry, both shared a fondness for the enlivening musical phrase of unexpected, odd numbered length, usually three or five bars. Yet Mozart’s reputation dominates. As a result, referring to Bologne by the name of another, even as it attempts to celebrate the unknown by comparison, also serves to obscure Bologne’s originality, individuality, and influence.

The Chevalier was a unique Parisian celebrity, who combined virtuoso skills as a violinist with his virtuosity as a fencer. According to one of his primary biographers, Gabriel Banat, facts about his life might be few and far between if not for Bologne’s undisputed prowess with a sword. While the composer’s biographers were prone to elaborate mythologizing, the chroniclers of Saint-Georges the fencing master were more precise. Even so, recent sources have continued to provide important corrections, for example, showing that his family name was long misspelled as “Boulogne.” Born, most likely, in 1745 on the Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe, a French colony, the composer adapted his name and title from that of his father. Bologne’s father was the wealthy planter and former councilor at the parliament of Metz, Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges. His mother was a teenaged woman named Anne, known as “Nanon,” who was enslaved to his father’s wife, Elisabeth Mérican. That enslavers considered the sexual availability of those they enslaved to be no less their “property” was horrifically common.

Little reliable information is known of Bologne’s early musical education, but musical study was undoubtedly included in his broad classical training as the son of a European nobleman. In this era, it was not unusual that the male child of an enslaved worker would be accepted as his own by his white European father. According to André Maurois, “It was customary that colons return to France with their sons of semi-African blood, leaving their daughters in the islands.”

In 1753, Georges returned to France with his seven-year-old son Joseph to provide for his education. The first solid evidence of the young violinist’s musical career dates from 1764, when Antonio Lolli composed two concertos for him. By 1769, he was performing in Paris with composer François-Joseph Gossec’s orchestra, Le Concert des Amateurs. Based on the dedication of Bologne’s trios, Gossec, an important figure in the development of the French symphony, may well have been his composition teacher. In 1771, Bologne became concertmaster and, when Gossec left Les Amateurs to direct the Concert Spirituel in 1773, Bologne assumed leadership of the orchestra and dedicated himself to a career in music.

Despite his talents and professional accomplishments, Bologne faced overt

racism during his career. Some critics, for example, while acknowledging his achievements as a violinist, conductor, and composer, dismissed the possibility that one descended from Africa could exhibit true artistic originality or “genius.” Bologne’s musical works were thus sometimes criticized as “imitations,” “quite lacking in invention.” Most dramatically, in 1776, when Bologne aspired to become director of the Académie royale de musique, later known as the Paris Opéra, a racist attack derailed his candidacy. As a composer, virtuoso performer, and the director of the most disciplined orchestra in Paris, Bologne was the obvious choice. He lost the position, however, when three of the Opéra’s leading ladies petitioned Queen Marie Antoinette for his rejection, claiming their honor would be compromised if they had to take orders from a mulatto. Rather than embarrass the queen, Bologne withdrew his name from consideration, and the position remained unfilled as no one else could match Bologne’s qualifications.

Bologne’s first compositions were a set of six string quartets published in 1772. Today he is known almost exclusively as a composer of instrumental music — mainly violin concerti and other orchestral compositions. His eight symphonie concertantes were particularly influential and helped shape this new, distinctively Parisian genre that grew from the Baroque concerto grosso. The concertante combined old and new, featuring one or more instrumental soloists (usually two violins in Bologne’s case) in musical conversation with the orchestra. Bologne’s own instrumental virtuosity coupled with his skillful knowledge of the orchestra’s possibilities seems to have inspired an expressive inventiveness that influenced the genre as a whole, including Mozart’s celebrated Symphonie Concertante for violin and viola. Given this focus on Bologne’s instrumental accomplishments, it may come as a surprise that after 1778, except for a final set of string quartets, the composer dedicated his later career exclusively to opera and song.

It is vital to recognize Bologne’s operas for at least two reasons. One is that the composer’s vocal writing may present his most vibrant artistic accomplishments. Haymarket Opera Company Director Craig Trompeter has remarked, “I find his writing for voices and dancers to be even more emotionally compelling and lyrical than his instrumental concert music.” To know his operatic music is thus to know Bologne the composer not only more fully but, arguably, at his artistic pinnacle.

The second reason is that opera was the most prestigious musical genre in late 18th-century France. The Querelle des Bouffons [Quarrel of the Comic Actors] of 1750s Paris was the turning point. It gave birth to a broad public debate about the musical art and sparked the creation of a theatrical press. Pitched as an aesthetic battle, the Querelle pitted French theatre against Italian, as well as composers Jean-Philippe Rameau and Jean-Jacques Rousseau against one another. It also challenged the French operatic tradition of tragédie lyrique, first introduced by Jean-Baptiste Lully, to accept more contemporary plots with spoken dialogue and lowborn, everyday characters.

Yet the aesthetics of French opera were inseparable from contemporary social politics. As the opéra comique developed, so too did Enlightenment social principles including individual liberty that, in 1789, would usher in the French Revolution. Bologne’s operas fully participated in this pre-Revolutionary negotiation of social ideas through art. Fortunately, following the withdrawal of his candidacy to lead the Opéra, Bologne found a home for his operatic ambitions in the circle of Charlotte-Jeanne Béraud de La Hay de de Riou (1738–1806). Known as the Madame de Montesson, she was the mistress and later morganatic wife of Duke Louis Philippe d’Orléans. As a result, she had the financial means to create a private theater company.

Bologne’s third comic opera, L’Amant Anonyme [The Anonymous Lover]

premiered on March 8, 1780, likely at Montesson’s residential theater. Based on a play of the same title by Madame Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis (1746–1830), it is Bologne’s only full operatic score known to have survived. A sometimes-problematic copyist manuscript is held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (cote D-13863). It was edited for this recording by Gregg Sewell.

The opera is set in the rural French countryside, to which the young, noble-born widow Léontine (a soprano) has retreated following the death of her unfaithful husband. The plot involves an improbable love “triangle” between just two characters: Léontine and Valcour (a tenor), who woos his love in secret as the “Anonymous One.” Despite the ruse that enables the plot, some comic moments, and the opera’s happy ending, this opéra comique is not necessarily or exclusively humorous. In fact, the French genre combined the comic and serious and could even be tragic. Associated with the Parisian theater of the same name, the phrase opéra comique simply signals that the work contains spoken dialogue, rather than sung recitative.

The opera’s remaining characters include a pair of confidants: the baritone Ophémon, who is both Léontine’s aged tutor and Valcour’s co-conspirator, and Léontine’s friend Dorothée. Featuring spoken dialogue but no aria, duet, etc., the role of Dorothée may originally have been performed by the Madame de Montesson herself. On this recording, however, the role is performed by a soprano who joins the choruses, a decision that enhances both drama and music.

There is also a second pair of lovers: the villagers Jeannette and Colin. Also sung by a soprano and tenor, these young lovers parallel Léontine and Valcour to offer a model of true love, devotion, and delight. They further represent the truth and wisdom of the French people, offering a revolutionary example and inspiration to the nobility.

The opera begins with a three-part Italian overture, performed by an orchestra of strings plus basso continuo with pairs of flutes, oboes, bassoons, and horns. In contrast to the two-part French overture, the tripartite Italian variety features brisk outer movements with a slow central episode. As he does throughout the opera, Bologne draws upon characteristic dance forms, such as the courante, menuet, sarabande, gavotte, bourée, and gigue, to establish character and emotional affect. The fleet opening section, seemingly in the style of a triple-meter Italian corrente, immediately brings the virtuosity and precision of Bologne’s symphonic voice to the fore. The slower middle episode in duple time evokes the opera’s romantic plot, as the upper strings plus flute converse with the lower strings and bassoon in a flirtatious, if restrained, aristocratic dance. First sounded by the upper instruments, each melodic gesture is immediately echoed below. The third and final section is a vibrant, celebratory dance, featuring the same imitative playfulness and coquettish interplay.

Act One begins with an aria in a noble triple-meter minuet rhythm, introducing the aristocratic character of Valcour, Le Vicomte de Clemengis (an administrative rather than hereditary title). His very name suggests his “valorous heart.” Having hidden his love from Léontine for years, he describes his torment and protests his fear that his devotion will never be reciprocated. Gentle falling melodic gestures depict his sighs. A dialogue with Ophémon ensues in which the tutor encourages Valcour to reveal his passion. Ophémon concludes their subsequent duet, urging “Osez declarer votre amour / Que vous obtiendrez du retour [Dare to declare your love and you will see it returned]. Having predicated his friendship with Léontine on Platonic constancy, however, Valcour is afraid he can never reveal his secret passion.

Bologne is a sensitive textual interpreter and musical dramatist. His use of melody, harmony, instrumental color, and rhythm combine to communicate each scene’s core emotional affect. Melodic interplay often illustrates the drama between the characters, while the gradually rising tension of each scene is propelled by the rising melodic compass and rhythmic intensity of the singers’ vocal lines. A scene’s narrative peak, for example, typically arrives as the singers reach their highest tessitura, often as a variation within an aria’s obligatory da capo repetition. Soprano Nicole Cabell noted in an interview that the “surprising range” of Bologne’s vocal writing demands that the vocalist “be able to sing comfortably in the highest register… maintaining a higher-than-expected tessitura.”

Scene three introduces Cabell’s character, the heroine Léontine, fretting over a bouquet and letter from the mysterious but seductively romantic “Anonymous One.” Ironically, Valcour is asked to read his own ghostwritten letter, which asks Léontine to carry the flowers at the upcoming village wedding as a signal of encouragement. A furious ariette ensues in a turbulent C minor. Its driving bass line underlines Léontine’s determination to refuse her unknown admirer. She proclaims, “rien ne peut toucher mon coeur” [nothing can touch my heart]. Yet a lilting, contrasting episode in C major follows in which she confesses that these anonymous overtures have intrigued her. The da capo repeat of her opening refusal, however, reaffirms her resolve, the apparent finality of her decision punctuated dramatically by repeated high C’s. Valcour, of course, has now witnessed her indecision firsthand and plays to both sides of the question, at once

testing Léontine’s openness to love and surreptitiously nurturing her passions.

Their flirtatious debate continues with Valcour reversing course and encouraging Léontine to “surrender” to the Anonymous One’s request. Seemingly on cue, a lively chorus of villagers enters accompanying the soon-to-be-married Jeannette and Colin. The assembled celebrate the nuptials of the village couple, while singing the praises of their noble mistress Léontine. The episode emphasizes how unusual Léontine is as a feudal lord, even in the fictional imaginations of opera: she is a landowner and a socially independent 18th-century woman.

In the grand French tradition, an extended ballet ensues to an exclusively orchestral accompaniment, this one in five contrasting sections and styles. Jeannette and Colin then offer thoughts on love to Léontine. Their musical counsel concludes: “Le vrai bonheur de la vie est de savoir bien aimer” [Life’s true happiness is knowing how to love well].

In the subsequent dialogue, Valcour “pretends” to be the Anonymous One and throws himself at the feet of Léontine, who collapses into Dorothée’s arms in surprise. Still uncertain how Léontine will ultimately react, Valcour passes off his revelation as a joke. Act One concludes with a quintet featuring Léontine, Valcour, Ophémon, Jeannette, and Colin, each processing the event from their own perspective in a delightful ensemble of musical and dramatic counterpoint. This skillful compositional display becomes all the more impressive when one remembers that Bologne wrote L’Amant Anonyme ahead of all of Mozart’s “major” operas (six years before Figaro, for example).

Act Two begins with the turbulent churning of the orchestra to introduce an extended accompanied recitative in which Léontine confesses her despair and confusion, again in C minor. She finds herself receptive to love, while conflicted by the dual pull of her attraction to the anonymous admirer and her devotion to Valcour, even despite his “coeur froid” [cold heart]. A two-part aria ensues, closing with an insistent and urgent “allegro” in which Léontine demands that “Love, become more favorable toward me” or “stop tearing my heart apart.”

Ophémon enters with something to confess to Léontine, providing an excuse for an extended duet in variation form. Léontine insists that Ophémon reveal his news, while Ophémon distracts and delays. He eventually confesses that he has encountered her secret suitor. Unable to describe him in detail, Ophémon says only that he looks a bit like Monsieur Valcour. Léontine wishes that Valcour could love her as truly as the Anonymous One, yet despairs of the impossibility. Ophémon then sings the aria “Aimer sans pouvoir le dire” [To love while unable to declare it], recounting the Anonymous One’s expressions of devotion and his fear that only death can bring an end to his unrequited romantic agonies. The

Anonymous One has one remaining hope, however. He has seen Léontine carrying his bouquet and wishes to meet her privately, and at once, to confess his passion. Léontine fears for her honor and Ophémon proudly reports that he has already dismissed her admirer, claiming that Léontine had only wanted to tease him. Appalled by Ophémon’s callous treatment of the Anonymous One, Léontine insists on meeting him, if only to correct this insult to true love.

Torn between her conflicted impulses, Léontine then sings the extended B-flat major ariette “Du tendre amour” [Of Tender Love], confessing the widow’s growing sensitivity to the arrows of new love and her resulting torment. Soprano Nicole Cabell calls the aria her “favorite” and the opera’s “showpiece.” It features “a beautiful, long line and declaration of various emotional states.” For Cabell, “it is a gorgeous piece of music,” and one that “can be a wonderful stand-alone piece.” The coloratura melismas of the vocal line suggest the flames of passion that overwhelm Léontine, while Boulogne uses Sturm und Drang chromaticism to depict her internal emotional conflict. The da capo form again serves to propel the dramatic result, as the melismas return to reveal the still burning flames of love in Léontine’s heart. (Because of its similar characteristics, album producer James Ginsburg dubs “Du tendre amour” this opera’s “Dove sono” — again noting that Mozart wrote his celebrated soprano showpiece six years later.)

Anxiously awaiting the arrival of her anonymous admirer, Léontine is interrupted by none other than Valcour who, having observed her distress, now appears to offer the support of “tendre amitié” [tender friendship]. Fearing an awkward confrontation when the Anonymous One arrives, Léontine attempts to dismiss Valcour, who stubbornly refuses. The conflict propels an extended duet in which Léontine implores him to depart and Valcour insists on staying. Bologne’s music gradually intertwines their relationship more and more deeply.

In the dialogue that follows, Léontine confesses her platonic love for Valcour in the hopes that he will depart. Instead, he again falls at her feet and now kisses her hand. Léontine is both confused by his behavior and anxious about the Anonymous One’s imminent arrival. Knocks at the door are heard, and Léontine collapses. Finally satisfied of Léontine’s devotion, Valcour reveals that he himself is the anonymous lover. In shock about the happy resolution, Léontine and Valcour, joined by Ophémon, sing a trio. Its halting lines are interrupted by rests emphasizing Léontine’s astonishment.

In the final scene, Dorothée returns, delighted to discover that Valcour is the mysterious and devoted suitor. There will now be a double wedding and a series of dances shift the mood towards increasing celebration and gaiety. The village chorus soon joins the quartet of lovers — Léontine and Valcour, Jeannette and Colin — in a celebration of true love. Running passagework in the strings recalls the burning flames of love’s passion, while the flutes interject with bird song, suggesting that nature itself approves of their unions. One particularly elegant musical figure here is the long sustained note sung twice by Jeannette. It appears to represent enduring, unceasing love.

The opera concludes with a rousing, syncopated contredanse [country dance] that gives the whole company an excuse to celebrate. Its contrasting minor episode features the oboes and evokes a folk bagpipe. The da capo return of the opening folk melody brings the opera to a close, again emphasizing that the root of all truth and authority lies in the French people. This is not too strong a claim as the contredanse was special in that the dancers form an ensemble of equals, avoiding the physical performance of hierarchy so much a part of more typical court dances. To conclude an opera in 1780 with a contredanse was to make a powerful social statement.

The first to make Joseph Bologne’s operatic creativity available on record, this Cedille release helps to redress our understanding of the composer’s artistic efforts, balancing the extant recordings almost exclusively of his instrumental compositions. The first vinyl recording of Bologne’s symphonic music dates from 1957. It remained an outlier until the 1970s, when four releases documented a handful of his quartets, concertos, and sonatas. More than 25 years would elapse before Cedille released Rachel Barton Pine’s performance of Bologne’s A major Violin Concerto Op. 5, No. 2, in 1997.

The question remains, however, why was the music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, in need of recovery? Once well known, why did his music disappear? His fame during his lifetime led to contemporary biographies and much of his music was published, including his concertos, symphonies, concertantes, and songs. Nevertheless, the name of Joseph Bologne disappeared from music history. The reason, unsurprisingly, is racism.

In the wake of the French Revolution and its calls for “Liberté,” France abolished slavery in 1794. In 1802, however, having destroyed the nascent Haitian democracy of Toussaint-Louverture, the future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte reestablished slavery, making France the only country in history to restore slavery after it was outlawed. (France would not finally abolish slavery until 1848.) This reversal in the concept of human value required a parallel erasure of Black humanity. The accomplishments of Afro-French artists, however, stood in sharp contradiction to French government policy, and thus the story of Joseph Bologne, the inimitable Chevalier de Saint- Georges, was suppressed. Fortunately, history can be recovered, and this recording is one such step. Much work remains to be done, not only to better understand the music of Bologne, but to fully restore the powerful voices of the many other artists of color who have been unjustly silenced.

Mark Clague is Professor of Musicology and Associate Dean at The University of Michigan (Ann Arbor). He serves as editor-in- chief of the George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition and as Chief Advisor to the RBP Foundation’s Music by Black Composers project. His recent publications include O Say Can You Hear?: A Cultural Biography of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Album Details

Producer

James Ginsburg

Engineer

Bill Maylone

Recorded

June 20, 2022 – June 22, 2022

Sasha and Eugene Jarvis Concert Hall at DuPaul University (Chicago)

Graphic Design

Bark Design

Cover and Production Photos

Elliot Mandel

CDR 90000 217