Store

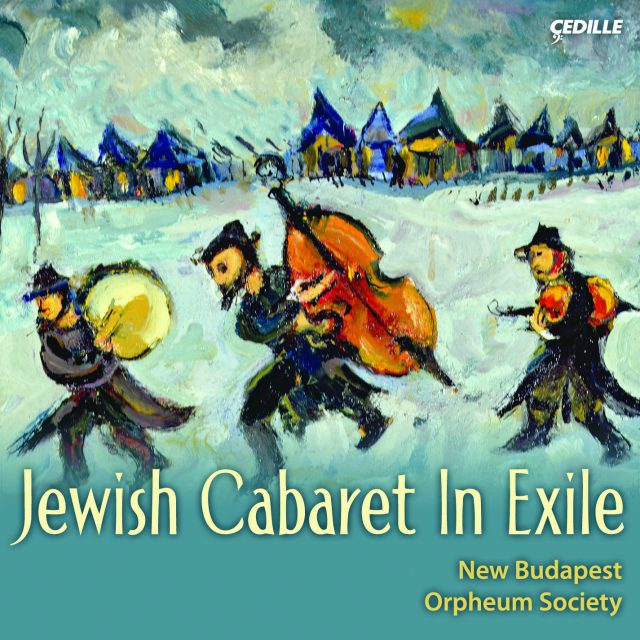

The New Budapest Orpheum Ensemble’s Jewish Cabaret In Exile follows its acclaimed recording debut, Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano — Jewish Cabaret, Popular, and Political Songs 1900–1945.

On the new CD, the University of Chicago-based troupe offers the fruits of its latest research into Jewish popular music of the early to mid-20th century — repertoire that is “often funny and always fascinating” (Audiophile Audition) — and the culture that produced it.

The ensemble performs piquant songs of love, lament, observational humor, and social satire with an “engaging zest” (Fanfare) that has charmed concert audiences in the U.S. and Europe. The program includes songs by Edmund Nick, Hanns Eisler, Friedrich Holländer, Victor Ullmann, and others.

Preview Excerpts

Die möblierte Moral (The Well-Furnished Morals)

MOSES MILNER (1886 – 1953)

Mordechai Gebirtig

Abraham Ellstein

Hanns Eisler

VIKTOR ULLMANN (1898–1944)

Three Yiddish Songs (Brezulinka), op. 53 (1944)

GEORG KREISLER (b. 1922)

HERMANN LEOPOLDI (1888 – 1959) and ROBERT KATSCHER (1894 – 1942)

MISHA SPOLIANSKY (1898 – 1985) / MARCELLUS SCHIFFER (1892 – 1932)

Friedrich Hollander (1896 – 1976)

Artists

25: Lyrics by Theobald Tiger (Kurt Tucholsky)

Program Notes

Download Album BookletJewish History as Exile

Notes by Various

Song has been the language of exile throughout the long course of Jewish history. Song chronicled the possibilities of survival, through hopefulness and in despair. Song provided a home in which the language of the everyday lived on, be that language Yiddish or Ladino, or even more the literary languages that never would have known modernity without Jewish influence. Song preserved all that was precious. Song resisted oppression and the oppressors, fighting back even as the last resort. Song struggled under the burden of futility and irony. In the exile unleashed by diaspora (the centuries of exile endured by Jews after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 ce), and holocaust alike, song echoed the language of the victor no less than of the vanquished (see Kertész 2003).

Jewish cabaret was born of and borne by the exiled language of song, and it was thus destined to perform a vexed doubleness. Bertolt Brecht’s “Auf den kleinen Radioapparat” (“On the Little Radio”) and its transformation into one of the great anthems of Jewish cabaret in exile, Hanns Eisler’s “An den kleinen Radioapparat” (Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano track 18), could not bear more trenchant witness to that doubleness. Through the 1930s and 1940s Brecht and Eisler followed intersecting paths of exile, variously through Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, the United States, and then back to a Germany divided into two.

They did not travel alone on these paths of exile, but were joined, however briefly, by fellow travelers of exile, among them Kurt Tucholsky, Anna Seghers, Friedrich Holländer, Joseph Roth, Kurt Weill, Arnold Zweig — the cast of characters envoicing the language of exile is as endless as exile itself. When these fellow travelers survived — and many did not — they translated the fragile and traumatic world around them with the language of exile. Their medium of translation was the common voice that song, like no other form of expression, made possible.

Cabaret conjoins the paths of exile as metaphor and reality, always taking the closing command of “To the Little Radio” seriously. In his setting of the Brecht poem, Hanns Eisler sets a critical modulation in motion. Indeed, he did this with all the Brecht poems that he gathered from the poet’s Hollywood collections (see Brecht 1981: 727–821) and reassembled for his Hollywood Songbook (see Roth 2007; Bohlman and Bohlman 2007). The slight adjustment of the title from “On the Little Radio” to “To the Little Radio” affords the song a new agency. Ironically, the radio in the song embodies the disembodied voices of the poem. Whereas the text comes to a halt in the poem, in the song it to continues to ring forth. The music that continues to ring forth because of those who carried these repertoires with them during exile powerfully inflects the language of that exile with the linguistic and political dialects mustered by cabaret.

The creators and performers of cabaret are unusually and uncannily drawn into its rootedness in the rootlessness of exile. It is in the uncanny transience of cabaret, moreover, that the question of its Jewishness arises. The songs on this CD raise that question in many different forms, but they resist conclusive answers to it. Cabaret does not lend itself to a division between Jewish and non-Jewish. Brecht, after all, was not Jewish, Eisler was. Jewish cabaret forms when the non-Jewish and Jewish intersect, when, that is, they become inseparable. What becomes evident in the songs gathered by the New Budapest Orpheum Society for this CD is that, in the course of the twentieth century, so dominated by exile, cabaret was overwhelmingly Jewish. Jewish cabaret lent its voice, insistently, to the languages of exile (see Bohlman 2006).

The link of cabaret to Jewish exile draws us into larger discussions of Jewish music itself, so fraught throughout cultural history with the dilemma of identity. So explicit is exile in Jewish music that we might ask whether it is fundamental to making music Jewish. Friday evening Sabbath services open when Shechina, the feminine presence of God, is musically welcomed into the Jewish community gathered in the synagogue with the song “Lecha dodi,” (Come, My Beloved). Symbolically, also physically and musically, the Sabbath Bride of “Lecha dodi” thus represents a moment of rest in the journey of exile and diaspora.

Diaspora, in its core of historical meaning and capacity to generate diversity within Jewish culture, also provides a critical repertory of metaphor to make music Jewish within exile. How, of course, is it possible to separate exile from diaspora? Ritually or musically? Placelessness and pogrom (the physical attacks on and destruction of Jewish towns), too, accompany diaspora and are accompanied by exile, realizing the aesthetics of silence and tragedy, but also of soteriology (the capacity to arise again from destruction and death), that is of revival (see, e.g., Adler 2008; Benz and Neiss 1994; Mertz 1985; Sebald 1992). Jewish folk song and traditional music assume new form through revival as icons of wandering and exile, the path even of Jewish children toward a promised land, as in the “Wanderlied” published by the great chronicler of Jewish music in diaspora, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, in Figure 1 below juxtaposing the very humanness (Mensch) of exile with song:

- Gad, Efraim, Chaim, Dan,

Let’s go, we want to journey to the Garden of Eden!

Stand in rank and file,

We soldiers, march forward!

One, two, halt! One, two, halt!

- Hands to your side, back straight!

Pay attention to where you’re going!

Everyone march straight ahead!

Make sure you march quickly on!

One, two, halt! One, two, halt!

- The sun is as warm as the oven coals,

Sweat runs from every brow;

But be silent! Put your hand over your mouth!

Who would hum on a day like today?

One, two, halt! One, two, halt!

Fig. 1 – “Wanderlied für Kinder” / “Marching Song for Children”

by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn

The cabaret stage gathers Jewish songs of exile, revoicing them as narratives of and responses to the exile from which the cabaret performer takes them. We might turn briefly to the endeavors of the cabaretiste, searching for the aesthetics of exile on the stage of the Jewish cabaret, which so often provides the waystation of exile.

Jewish cabaret is a phenomenon of modernity following the industrialization of rural Jewish life that swept across Europe at the end of the nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1880s especially, Jews were forced once again into exile, from the country to the city to escape the accelerating pogroms and prejudice of European non-Jewish society to find jobs in the factories of Vienna, Budapest, and Berlin, and to send their children to universities and trade schools. Exile and the displacement of Jewish families to the city fill cabaret songs, often tales of the hapless immigrant, barely able to speak German, who nonetheless finds the wherewithal to earn a fortune or find success (see, e.g., tracks 1–6 on Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano).

The modern city as a waystation for exile is everywhere in the songs on this CD. Indeed, from song to song we follow a type of city map in the broadsides we bring to the stage, particularly in the songs by Hanns Eisler and Edmund Nick to texts by Kurt Tucholsky and Erich Kästner. By the end of World War I and with the collapse of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, the streets, clubs, and stages of Berlin, Munich, Prague, and Vienna were filled with popular music, created and performed by Jewish immigrants. These cities each boasted their Tin Pan Alleys, and like their American counterpart, they were cauldrons for Jewish popular music.

The songs on this CD also represent people and music in movement, which increasingly expanded to exile in the twentieth century. Even as modern exile songs come into existence, they reflect the dynamic flow of recent migration and centuries-old diaspora. Fifty years later, on the eve of the Holocaust, another type of movement enters the songs (listen, especially, to the songs by Hanns Eisler on the present CD). In the 1930s, as Jews were increasingly excluded from public life by the German and later Austrian fascist governments, they faced decisions about leaving the worlds to which they had adapted for several generations. They faced, in a word, exile, and accordingly Jewish song turned into a voice for exile — a means of responding to the crisis that loomed ever larger on the horizon. This is ultimately realized in the opening lines of songs such as “Hotel Room 1942,” from another of the great monuments to exile, Hanns Eisler’s and Bertolt Brecht’s Hollywood Songbook (listen to the recording on track 15 of the CD accompanying Bohlman 2008b).

Against the white-washed wall stands the black suitcase, filled with manuscripts.

Beyond it rests the smoking materials, next to the copper ashtray.

With its restaging of Jewish cabaret, the New Budapest Orpheum Society illuminates the path of Jewish exile against the backdrop of the tragedies of twentieth-century history (for a collective biography of musicians repressed by the Holocaust see Weniger 2008). Each path of exile is given its own musical narrative — realized on this CD in the themes of each section or set of songs — which the ensemble brings to life in settings and arrangements, many of them never previously heard, most recovered from the tragedy of World War II and the Holocaust. In addition to the songs from Central Europe during the era of fascism and holocaust, the New Budapesters also sing songs from Yiddish cinema, which thrived only during the 1930s in Poland before destruction in World War II, but form a counterpoint with Friedrich Holländer’s brilliant parodies, composed in Berlin and Hollywood alike. This CD also includes songs from Jewish musicians who did not survive, such as Viktor Ullmann’s concentration-camp songs, Three Yiddish Songs (Březulinka), op. 53 (1944), which sustain musical life even in the face of death.

The tragedy in the songs of Jewish cabaret in exile is never a cry of hopelessness. Through song, poets, composers, musicians, and audiences all confronted modernity in its most brutal forms, but they knew that music made crucial forms of survival possible, above all through exile. The songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile live, ultimately, in the generations that follow, the musicians who perform them and the listeners who experience their power. In this way, musically, the New Budapest Orpheum Society keeps the promise to Eisler, Brecht, and the other poets and composers whose songs fill this CD: we “will not fall silent suddenly.”

Political Song and Jewish Cabaret

Jewish cabaret is public and political. Those who create and perform its songs take direct aim at the ills and evils of society, and in so doing the artists of cabaret take the side of those in disadvantaged positions. Cabaret is the music of alterity, that is, of an otherness born of the abuse of power. Taking the side of the Other and the Outsider also places cabaret performers at risk. The politically powerful often seek to drive cabaret players from the stage. The choice faced by many cabaretists, including most of those for whom the songs on this CD were created, was silence or exile. With few exceptions, the second option was always preferable.

The potency of popular song to mobilize the political lies in the ways it mixes genres. By turning genres inside-out and juxtaposing them in unexpected ways, the songsmith and composer unleash the play of parody and double entendre. Tunes move malleably from one repertory to another, or from folk to popular to classical genres, and in so doing they expose meanings that might not have been originally apparent. The quotation of the melody of the German national anthem, the “Deutshlandlied” (commonly known as “Deutschland über alles”) that opens the Eisler-Tucholsky “Unity and Justice and Freedom” on this CD, therefore, undermines rather than supports the values of the song’s title. Song elements that at first hearing seem innocent — the frequent reliance on folk melodies that many hearing this CD will think they have heard before — often contain some of the most cutting social critique.

A song text that at one moment seems cloyingly nostalgic launches a full-fledged social commentary the next. The satirical and the serious intersect, as do the lament and the love song. At first hearing it may surprise many to hear the several instances of lullaby (e.g., “The Father’s Lullaby” and “The Little Birch”) and tango (e.g., “Deep as the Night” and “Marianka”), but it is precisely in their familiarity that they become the catalyst for the deeper political meaning evident in the parody of lullaby employed by Hanns Eisler for “My Mother Is Becoming a Soldier.” Hybrid genres, moreover, challenge the censor because their “real meanings” are difficult to pin down. The moment everything seems to make sense, the political songsmith slips into another style or skirts the subject that is too obviously suspect. Chameleon-like, political song acquires its power as more and more hybridity accrues to it.

When examining the ways in which genre undergoes processes of hybridization in political song, the New Budapest Orpheum Society begins by taking the idea of genre in its rather literal sense. The genre lying at the heart of many songs on the CD is the ballad, in other words the strophic narrative form that unfolds as a series of dramatic scenes. It is this narrative-musical structure that allows new meaning — the trauma of the concentration camp — to accrue to the folk songs of Viktor Ullmann’s Three Yiddish Songs. The ballad contains a cast of characters who are stereotyped and idealized, who are then mixed with a real and historical cast of characters. The mother seeking the lost love of her son (“Song of the Lost Son”) is both real and ideal, a symbol of a nostalgia generated by the modernity of Weimar Germany. A Tucholsky couplet (“Couplet of the Beer Department”) locates a cast of comic characters on the stage, where they become metaphors for the machines of social decay.

The ballads rely on hybridity in still other ways. They rely on the common practice of connecting folk song in oral tradition to popular and art song in written tradition. The poetry of Erich Kästner, Kurt Tucholsky, and Georg Kreisler appeared first in literary journals and newspapers, from which songwriters adapted them because they dovetailed with popular tunes that might well lead them to the top of the charts. Recognizing the pregnant moment resulting from the cross-fertilization of the oral and the written, Kästner and Tucholsky, and the composers with whom they collaborated in the first and fourth sets of songs on this CD deliberately employed genres at the nexus of folk, popular, and art song, not just the ballad but also the Moritat (the German street broadside, the text of which expresses a moral lesson) and the worker’s song. With each new genre and style added to the mix, the songs resonated for new audiences and more diverse publics.

The frequent presence of humor in cabaret songs also contributes to the ways in which they mix genres and engender complex meanings. Humor provided a means of keeping ideological opposition alive on the popular stage, allowing performers to chronicle the lives of the working class and poor, or of urban immigrants escaping the pogroms and political repression of Eastern Europe for the promise of the industrial city. In many of the songs on this CD, the listener meets individuals whose follies have placed them in improbable situations where their actions, whether in vain or simply misguided, are meant to be greeted by laughter, but also by serious reflection on the tribulations that have been inflicted upon them. Humor, the stock in trade of a cabaret ensemble such as the New Budapest Orpheum Society, seldom remains isolated in the political songs. The songs stir a full range of emotions, which together make it possible for audiences to identify the songs with their everyday worlds.

It is in popular song, especially, that the political undergoes a transformation that simulates the everyday. The poets of the 1920s and 30s crafted an aesthetic aimed at rescripting seemingly extraordinary events so that they felt commonplace, hence drawing all citizens close to the events in the texts. To match the shift of the political to the everyday in the poetic texts, the composers whose song settings fill this CD also forged musical styles and vocabularies that enhanced the sense that the poems and music belonged to the people and gave voice to their concerns. Cabaret provided an impetus, ideologically and musically, for a modulation of the modernist into the everyday, a stylistic sea change that one hears most dramatically in the differences between Hanns Eisler’s Newspaper Clippings and his settings of Tucholsky texts. Working with musical materials that stressed the familiar and the accessible, composers of the interwar period and the Holocaust, such as Eisler and Kurt Weill, crafted melody and harmony that possessed the ring of the popular, drawing audiences to their song repertories while their power lay in their textual clarity and steadfastness of purpose. It is this quality we encounter when we hear these songs, recognizing some as enduring popular songs (e.g., Weill’s “Mack the Knife” or Eisler’s “Solidarity Song”; cf. Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano track 17) and feeling an affinity with all as somehow “our” songs. In countless respects, they have also become some of the most memorable musical moments of the twentieth century.

There are yet more reasons that many of the songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile feel strikingly familiar: In one version or another, these songs found their way to the stage, where some thrived and a few even became hits. Stage, in this sense, has both general and specific meanings, literal and figurative forms. From the end of the nineteenth century until the 1930s, the one stage that would pick up many of these songs was the cabaret, with its mixture of skits, satirical and sentimental songs, and parodies of scenes from operas and operettas alike. The sensibility of cabaret runs through all the songs, for it was the theatrical venue that attracted Kurt Tucholsky and Friedrich Holländer in the 1920s and 1930s just as seductively as the creators of broadside and couplet (comic scenes, often sung by duos on the cabaret stage) in fin-de-siècle Vienna and Berlin. After World War II, that sensibility once again attracted the socially engaged singer-songwriter to the cabaret, as the songs by Edmund Nick, Hermann Leopoldi, and Georg Kreisler richly illustrate.

Succeeding in the world of the popular stage, of course, meant that a song had to be flexible. Cover versions were the rule rather than the exception, and parody and stereotype left no one’s sensibilities unchallenged. The stage allowed tradition to be historicized no less than bowdlerized. It was on the popular stage, moreover, that the most serious issues of the day could be clothed such that they would be recognizable to the audience while remaining opaque to the censors looking for hidden meanings while the actors and singers were wearing the real point on their sleeves. The composers creating the repertories on this CD fully recognized the political and popular potential of the stage. The listener will witness that recognition strikingly among the cabaret songs in the second set of songs with Yiddish texts, some seemingly sacred, others overtly secular, all engaging the musical possibility of the shift from cabaret stage to sound film. The range of theatrical genres is even more expansive in the songs by Friedrich Holländer and Hanns Eisler, both of whom wrote extensively for movies the moment sound film became viable. The hybridity of popular-song genres for the stage was revolutionary precisely during the era of the 1920s and 1930s, and beyond in the exile of the 1940s, when music for the cabaret found new homes on the stage of the American musical and the Hollywood film.

From their composition and dissemination to their performance and reception the songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile frequently had to tread a thin line between the sanctioned and forbidden, and between the legal and illegal. Their creators and performers also negotiated social and ethnic religious differences, particularly the distinctions between what was perceived as Jewish or not. Whereas some of the songs, especially those with an indebtedness to oral tradition (e.g., Viktor Ullmann’s Three Yiddish Songs), probably circulated almost exclusively in Jewish popular culture, many others are the products of remarkably fruitful collaborations between Jewish and non-Jewish musicians and writers. Collaborations such as those between Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht, or between Edmund Nick and Erich Kästner are notable because they so richly reveal that the sources for popular and political music in the twentieth century lay in the blurring of cultural borders.

The Jewishness of the songs, indeed, often remained open to question less for religious reasons than for political ones. For what kind of public were they intended? Just how did the Jewish and non-Jewish intersect and designate that public? To what extent were questions about race and religion being forced to the central position in the pre-Holocaust agendas of rising fascism? These were the questions tackled by Jewish popular musicians and the issues confronted head-on by Jewish cabaret, the tradition upon which the New Budapest Orpheum Society draws.

The metaphors and tropes of modern Jewish history run through these songs, transforming them into a roadmap through prejudice and peril alike, indeed through the multiple landscapes that stretched into exile. Thus this CD charts the course of a historical journey, fraught at every turn with detour and displacement, yet ironically following the path also familiar to people accustomed to discovering their “homeland in the book.” The security of the book, however, lay not in its permanence, which Nazi book-burnings in the 1930s directly threatened, but rather in its capacity to accompany exile, borne so often by song. Exile and its persistent counterpart in Jewish history, diaspora, also find their way into the journey that cabaret songs document. These are, indeed, the songs of exile and survival, which provided alternative courses for a journey encumbered by censorship and halted by book-burnings that threatened Jewish and non-Jewish poets alike. As political and popular songs, they survived by charting the very possibility of exile.

Toward a Poetics of Jewish Cabaret in Exile

Year after year, my soul has wandered,

Measuring the world in its pace,

Seeing with sadness so many happy lands—

Oh, soul, why are you so ill!

And yet my soul returned,

Coming from blossoming lands,

Into the land, poor and holy—

Poor and healing—like a cradle

Samuel Jacob Imber – “Gevandert hot yorn mayn sele” /

“Year after Year, My Soul Has Wandered” (from Imber 1912–1915;

from the German in Soxberger 2008: 22)

Does exile transform song? How is it possible to speak of an aesthetic of exile when it results from tragedy and in trauma? These questions, rather than their answers, accompany the poem that opens this section, one of the great Yiddish poetic anthems to exile. Samuel Jacob Imber (1889–1942) chronicled the life of exile that was his own, a life that ended when he perished in the Holocaust, killed in his own Galician border region shared by modern Poland and Ukraine. The nephew of Naphtali Herz Imber, whose poem, “Ha-Tikva,” serves as the text for the Israeli national anthem, Samuel Jacob Imber escaped pogrom and war in Galicia to arrive in Vienna and then the United States in the 1920s, where he became one of the great voices of Yiddish literary modernism.

Imber’s own life, like the allegorical soul in this poem, was in constant exile. It was only in poetry and song that it found its home, its “cradle,” that symbol of the lullaby, which also provides an essential link to many of the songs on this CD. With this poem, the aesthetics of exile and exile itself become one, far more than a symbol, rather a meaningful moment for the artistic realization of exile itself. It is to this end — this cradle of healing and holiness — that so many songs of Jewish Cabaret in Exile aspire.

An aesthetic of exile is only possible through the type of performativity that gives life to the cabaret stage. To this end, the songs of the New Budapest Orpheum Society constitute a performative act, empowering the ensemble to act upon its repertory as translators: hearing and listening, reading and singing, sounding and healing. Translation thus also becomes a creative form of artistic expression. Translation — and here we must be specific, for we mean translation that is intertextual, intergeneric, interactive — aspires to the possibility of a wholeness, seemingly rerouted and made ill by years of exile. Translation empowers with a new aesthetics and a new language, what Imre Kertész calls “the exiled language” (Kertész 2003).

The New Budapest Orpheum Society empowers translation in this way because we believe these songs are not shadows of the original, diminished in some way because of the loss of traces of originality. The translator musters many tools, which allow her even to continue the task of creating, not to complete it as such, but to expand — to listen between and beyond the rhythm of the poetry — to expand the stepwise journey of the melody. The translator — Ilya Levinson in his arrangements and orchestrations, Philip Bohlman in his live cabaret role as compère (the emcee who provides scholarly and comic commentary during performance) — dares to think that life can be breathed into fragments, and that the sounds of the poet’s voice need never be abandoned to silence. Translating the music of Jewish cabaret that has been displaced restores for it the place it has lost. This is the poesis of exile.

It is a poesis that has particular resonance in the context of work on Jewish history in the twentieth century, its trauma and tragedy. First, the translator in some measure searches for sound in the silence, searches for voice in the loss of voice. The poetic ontology must creatively be given to the silence. We act by listening to — by listening into — silence. Second, the translator breathes new life into the silence, but does not primarily use translation to rescue and reiterate the lost life, whereby it would only confirm loss by multiplying it. Third, the translation opens new and alternative modes of performing poetry and song. Through the translation of performance the New Budapest Orpheum Society seeks to know a new wholeness of place that at once recognizes and defies the impossibility of fully dislodging music from exile.

Music mobilizes the journey into exile by juxtaposing the everyday and the telos (the goal or end-point) evoked by the end of time. Time and timelessness become interdependent; ending and beginning become one (see, e.g., the treatment of time in Adler 2008). Accordingly, we find a proliferation of songs about journey in the aesthetics of exile. Songs of exile resist the journey beyond the homeland, coming to rest only through exile. Once again, a song joined by Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht in the Hollywood Songbook becomes itself far more than a symbol of exile and return.

Die Vaterstadt, wie find ich sie doch?

Folgend den Bombenschwärmen

Komm ich nach Haus.

Wo liegt sie mir? Wo liegt sie mir?

Dort, wo die ungeheuren Gebirge von Rauch stehn.

Das in den Feuern dort ist sie.

Die Vaterstadt, wie empfängt sie mich wohl?

Vor mir kommen die Bomber.

Tödliche Schwärme melden euch meine Rückkehr.

Feuersbrünste gehn dem Sohn voraus.

My home city, how does it seem to me?

After the massive bombing

I am coming home.

Where is it? Where is it?

There, where the monstrous mountains of smoke rise.

There it is, in the fires.

My father city, will it welcome me?

The bombers came before me.

Deadly swarms announce to you my return.

Firestorms precede the son.

“Die Heimkehr” / “The Homecoming”

(Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht; from Hollywood Liederbuch;

for a recorded performance by the New Budapest Orpheum society see the CD in Bohlman 2008b: track 19)

The paradox of a return that is preceded only by death becomes the arrival that marks the end of exile. That paradox is also evident in the final word of S. Y. Imber’s poem, Wiege, which lends itself to translation literally as “cradle” and metaphorically as “coffin,” suggesting both birth and death (see the discussion of lullabies on Jewish Cabaret in Exile that follows below). Eisler and Brecht’s “The Homecoming” is redolent with irony as the journey of exile comes to its end. We find ourselves at once consigned and resigned to an aesthetic of exile that is also an aesthetic of transcendence. At some point — along the journey itself — the boundaries between the two aesthetics blur. We recognize this as those following the aesthetic journey find they can no longer extricate themselves from it, can no longer find a detour from the path that lies ahead.

The songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile chart the very path of exile itself, each set articulating the conditions of transit along a journey consisting of one way station after another. Cabaret and the songs created for it depend on mobility, the capacity to create in vocal styles that admit to improvisation and changing possibilities for instrumental accompaniment and orchestration. The composer, poet, and singer-songwriter discover the materials for their songs in the everyday — vernacular speech, folk song and dance, fragments of speech and broken pieces of literary texts, the sounds of a world enriched rather than disarmed by the abrasive and the dissonant.

The way stations that unfold on this CD are broadly historical, beginning in the wake of World War I and the collapse of the long nineteenth century. They resume as cabaret launches response and resistance to the disintegration of the political climate between the wars, but they then accrue around new way stations in the 1930s, as cabaret realizes the new potential in sound recording and film. By the late 1930s cabaret, especially Jewish cabaret, is forced into the disturbing trajectories of inner exile and the trauma of the Holocaust. It is both telling and tragic that cabaret also survived to play again even at the way stations of the concentration camps, which all-too-often proved to be the final stage.

The CD concludes with groups of songs that chart new paths of transit: reprise, return, revival. Even at these way stations the composer and performer take to the boards, perhaps finding refuge in nostalgia, but more often opening new avenues for memory and memorial. The transits of Jewish cabaret in exile provide mirrors of the everyday and the longue durée of the Jewish experience of modernity. The way stations that form the sets on this CD remind us powerfully of the broad sweep of twentieth-century Jewish history.

The Songs

Growing from and responding to the class and religious difference, and political and ethnic diversity, of twentieth-century Europe, cabaret — and above all, Jewish cabaret — became the voice of the collective, striving for a common ground that all individuals and groups in European society could claim. From the vantage point of twenty-first-century revivals, the Central European Jewish cabaret that appeared in clubs, theaters, dance halls, and literary gatherings after the dissolution of the German and Austro-Hungarian empires in the wake of World War I might seem at first glance esoteric, the aesthetic fantasies and experiments of leftist intellectuals doomed because of the rise of fascism. Those who created and performed cabaret, however, spoke not only among themselves, but they conceived of an art-form that could penetrate to the farthest reaches of a society undergoing dizzying change.

The repertory chosen by the New Budapest Orpheum Society represents this passion to find the collective voice and enact the change necessary to halt and reform the slide into chaos. We have gathered songs from different media, different anthologies, and different stylistic directions. The songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile capture as many of those directions as possible. There are sets that hold true to the melos of folk song; others strive to be openly modernist; there are the nuanced gestures toward aesthetic trends evoking the everyday and those responding to an era of machines. The ways in which so many songs conform, even deliberately, reflect an awareness of the literary journal and the sound recording alike, both stressing the poignancy of the fragment. Perhaps most collective of all, many of the songs on the CD seized the aesthetic possibilities opened by film, especially those that could powerfully convey the ways in which music for the stage synthesized the collective.

Critical to the power of the collective voice was also the symptom of the dangers it faced: censorship, the destruction of resources, prejudice and racism, violence and the flight it necessitated. The collective voice of the song sets on this CD would not have been possible without a passion toward collaboration. In each set we see the ways in which cabaret brought poets, composers, and performers together. The opening set on the CD provides resounding evidence of one of the most fruitful and forgotten of twentieth-century cabaret collaborations, that formed by Edmund Nick (1891–1973) and Erich Kästner (1899–1974). In their day jobs, the two followed very different paths: Nick as a composer and music administrator, working especially with genres for the stage and new media, such as radio and film, and Kästner as perhaps the best-known German author of children’s literature in the twentieth century. Together, however, they created more than 60 songs. They collaborated before World War II, as Germany slid into the “great ennui,” and again after the war at the Schaubude cabaret in Munich. Neither was Jewish, though their biographies intersected with Jewish musical and literary traditions, forcing both into inner exile during the war (on the Jewishness of Jewish popular music see Bohlman 2006 and Bohlman 2008a: 237–45; on inner exile see Haarmann 2002). Coeval with the rise of fascism, both employed a critique of the collapse of German society and the growing danger to those who did not conform. Kästner’s novel, Fabian, of 1931 was a brilliant satire, which took the reader inside the bureaucracy of the office and into the cabaret alike, drawing fire from the German censors and eventually succumbing to the fires of the Nazi book-burning on May 10, 1933.

The early song collaborations of Nick and Kästner in Weimar Germany are largely forgotten, in part the victim of the historical moment of social upheaval they documented. The six songs of Die möblierte Moral (The Well-Furnished Morals) with which we open this CD clearly reveal why the New Budapest Orpheum Society has so actively sought to recover these songs. The lyrics of the songs wear social criticism on their sleeves, targeting the totally non-idealized world that had become the target of resistance from the cabaret stage. On the surface, the social worlds of songs inhabited by the wealthy and privileged, by those comforted by homes and hotels that shut out the rest of the world, and by the very ideal of maintaining the status quo contrasts with those displaced by familial and generational differences. Verse by verse, however, each song reveals a social despair that could not be sustained, especially in a Germany attempting to avoid the obvious rise of new forms of inequality and prejudice.

Fig. 2 – Cover of Nick and Kästner, Die möblierte Moral (drawing by Georg Grosz, 1922)

Musically, the Well-Furnished Morals speaks brilliantly to the diverse musical styles and meanings that are crucial to cabaret as music. Each song satirizes a different genre — a lullaby (“The Father’s Lullaby,” track 2), an elegy (“Elegy in the Forest of Things,” track 3), or a pair of tangos (again “Elegy,” track 3, and “The Chanson for Those Who Are Born Better,” track 5). Composed for voice and piano, the songs lend themselves to improvisation, which Ilya Levinson has exploited fully in his arrangements, at once capturing the jazz-inflected sound of the early 1930s and making place for the intervention of later styles (e.g., “The Song ‘Once Again One Must . . .’” that closes the set). Figuratively and literally, Nick and Kästner set the stage for a new moment in the history of cabaret, in which the collective voice gained even more power to muster difference and sharpen resistance.

The Yiddish songs that Stewart Figa draws together for the second set on the CD reflect the dual roles he knows as a cantor for a Conservative synagogue and a longtime engagement with the Yiddish stage in its many forms from the past century. In both roles, sacred and secular, he is indebted to repertories that confront the “end of time.” Yiddish theater, including Yiddish film musicals, thrived from the late nineteenth century until the late 1930s, that is, until the eve of the Holocaust. Its practitioners found their way to Vienna, Berlin, and the United States, where they were distinctive for the many ways in which they responded to the shifting contexts of Jewish identity, be these traditionally religious, as in Moses Milner’s “In the Cheder” or secular, as in Mordechai Gebirtig’s “Abe, the Pickpocket,” a folklike song that comes from the final days of the Polish Jewish community; Gebirtig himself perished, but the incomparable range of his poetic imagination survives in his poetry and songs. Abraham Ellstein’s “Deep as the Night” is a Yiddish anthem of a different sort, truly a hit song that has transcended the fate of the Yiddish theatrical tradition. Yiddish musicals and films survived the Holocaust, but at enormous cost: the deaths of many of the greatest performers and singer-songwriters, and of the audiences in Warsaw, Vilna, and Odessa that kept Yiddish song going.

With the two songs from Hanns Eisler’s Zeitungsausschnitte, op. 11 (Newspaper Clippings) we begin to follow yet another course of exile through the politics of the twentieth century, capturing a fleeting but also profound glimpse of the composer in transit and compositional style in transformation. Dating from 1925–26, the Newspaper Clippings appeared during the moment Eisler was moving from Vienna and resettling in Berlin and capture a moment in which he rethinks the very meaning of the material he uses create his songs. The reasons for his transit from Vienna to Berlin were many and complex. Biographically, the move intensified and focused his commitment to socialism, especially its engagement with the working classes, for it was upon arrival in Berlin that Eisler officially joined the Communist Party. Musically, Eisler was turning in frustration away from the modernism of the New Viennese School, above all Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he openly quarreled in 1926. He sought instead a music of the people, which could serve its collectives, among them the workers’ choral and theatrical groups in Vienna and Berlin (e.g., Das rote Sprachrohr), for whom he created new works.

“Little Marie” and “My Mother Is Becoming a Soldier” capture both the fragility and the conviction of this moment of transit in Hanns Eisler’s life. On one hand, they stunningly express the potential of an aesthetic formed from “found objects.” As their name suggests, the Newspaper Clippings are settings of texts from the press, in fact, of statements and advertisements from the classified sections of Viennese newspapers. Eisler sets them without author or addressee, elevating song to the role of social criticism. He adapts a modernist language to them, and in so doing translates them from a form of literal evidence of the everyday to an indictment of the historical moment. It is this process of translation that Ilya Levinson’s arrangements extends. On the other hand, Eisler’s settings of the Newspaper Clippings rely on a new commitment to the unmediated, direct response of music. “Little Marie” employs a style that struggles to break into dance, as the opening evocation of a slow waltz collapses into a rough march that cruelly draws attention to the classified author’s depiction of a physically deformed Marie, whose salvation lies ironically in the beautiful song of a German men’s chorus. Compared with the other lullabies on this CD, “My Mother Is Becoming a Soldier” is an anti-lullaby, violently shifting between the lyrical opening and the martial admiration of a child who watches a mother deluded by war march toward her eventual death. The dual meanings of Wiegenlied (lullaby) could not be more poignant and political: Cradle (Wiege) and casket become one.

The collaboration between Hanns Eisler and Kurt Tucholsky (1890–1935) that occupies the central position on the CD provides compelling evidence for cabaret at its most public and political. Eisler and Tucholsky had arrived in Berlin in the 1920s following paths that were far more similar than different. Both had served in World War I, Eisler in the Austro-Hungarian army, Tucholsky in the German, but the experience of war had turned them ideologically against the social and political elites that had long played the roles of power brokers in Central European history. Disillusioned, both found inspiration in the ideas coming from Eastern Europe and the growing influence of communism, which offered new alternatives to the status quo and economic decline of Weimar Germany. Perhaps more than any other cultural impetus from their turn to the politics of the left, it was the activist agenda of socialism and Marxism that shaped their artistic voices and led, by the late 1920s, to the common voice that Eisler and Tucholsky would find in creating songs for the stage.

A gifted writer who never found a true home and eventually took his own life in the despair of exile in Sweden after the ascension of Nazism in Germany, Kurt Tucholsky found his métier in the critical and satirical essence of the essay and the chanson text (for a collection of his newspaper and journal writing see Lenze 2007). It was song that provided the thread connecting his social criticism. On one hand, many of the poems he wrote for literary journals (e.g., the Weltbühne, for which he was an editor for many years) took the form of songs, with names such as couplet or in the form of narrative song genres such as “Berliner Drehorgellied” (“Berlin Hurdy-Gurdy Song”; ibid.: 41). On the other hand, Tucholsky sought inspiration, intellectual, if not spiritual and sexual, in the night scene occupied by cabaret, and this led him frequently to write reviews and criticisms about “Berlin Night Culture” or “Berlin Cabarets” (ibid.: 12–16). There were times when he wrote song texts and reviews so feverishly that he used pseudonyms — Theobald Tiger, Peter Panter, Ignaz Wrobel, and Kaspar Hauser, to name a few — and it was not long before his poetry found its way to the very stages it mirrored (Seheer 2008; see also Jelavich 1993 and Stein 2006).

As he was making his own turn from the modernist style of Newspaper Clippings to a socially and politically engaged art, Hanns Eisler discovered an ideal lyricist in Tucholsky (see the compilation of their songs in Eisler 1972). The poetry was already musical, but more important, it captured the images and imagination of the Berlin vernacular. Tucholsky’s lyrics were direct and biting, clever and funny. They epitomized the different possibilities for cabaret song as it found its way from the stage to the larger public sphere. They offered poet and composer alike a new template for the “poetics of exile,” for they decried the possibility of living in a society that continued to justify itself on the basis of war production and the repression of difference. Songs such as “Couplet for the Beer Department” and “Sweetbread and Whips” satirically undermine the mores of a German society driven to modernize and industrialize. The politics of “Unity and Justice and Freedom” and “To the German Moon” exposed the paradox of maintaining the German history that led to the destruction of World War I and the rise of fascism. If there is hopefulness in songs such as “Today between Yesterday and Tomorrow” and “Civic Charity,” it remains tinged with irony, ultimately more suitable for the stage of the cabaret than for the stage of history.

The six Eisler-Tucholsky songs on the CD mark a moment of dramatic change in the work of their creators and symbolically in the role of cabaret song in Central Europe. For Eisler, the vernacular voice-of-the-everyday that he found in Tucholsky’s poetry would shape the core of his output, soon thereafter in the collaborations with Bertolt Brecht in the late 1930s and 1940s, which in turn laid the foundation for a nascent musical aesthetics of the German Democratic Republic, to which Eisler returned after expulsion from the United States because of his politics (Bohlman and Bohlman 2007). For Tucholsky, irony soon turned to the politically engendered hopelessness that forced the most public Jewish social critic of his day into exile from Germany.

Fig. 3 – Hanns Eisler with Ernst Busch (after 1950)

The songs of the fifth set are among the most brilliant Lieder settings produced by the Czech-Jewish composer, Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944). They were created in the trauma of the path of inner exile that led to the concentration camps. It was in the camp at Theresienstadt/Terezín that Ullmann established a Jewish voice for his compositions, especially his vocal works. Ullmann grew up in an almost entirely assimilated world, in which he received virtually no Jewish education whatsoever. Coming of musical age in the expressionism of post-World War I Central Europe, he followed several distinctive modernist directions, enjoying acclaim in Czechoslovakia but also beyond its borders, especially in Germany. Forced from his position at the Stuttgart Opera, Ullmann returned to Prague after 1933, where he continued to compose until his deportation to Terezín in 1942. It was in the camp, with its diverse stages for musical performance, that Ullmann turned toward Jewish themes, setting songs in both Hebrew and Yiddish, neither of which he knew prior to the camps.

The Three Yiddish Songs of op. 53, also known as Březulinka, are products of Ullmann’s confrontation with his own Jewishness in the trauma of an everyday world that enforced Jewishness. An examination of the sketches for the songs in the archives of the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel, Switzerland reveals that Ullmann took the melodies and lyrics from a collection by M. Kipnis, published in Warsaw soon after World War I (Kipnis n.d.). He set the melodies more or less exactly as they appear in Kipnis, though he relied on a transliteration of the Yiddish texts. In virtually every respect, his settings of the Three Yiddish Songs represent a retreat into a musical inner exile. It is as if Ullmann was searching again for the sound and texture of folk songs before they reached the metropole. There are scarcely any traces of the expressionistic or modernist techniques of earlier Ullmann styles, which he also retained in works for the stage composed in the final year of his life, notably Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke (The Chronicle of Love and Death of the Flag Bearer Christoph Rilke) (1944).

“Berjoskele” (“The Little Birch”) opens the set as a lullaby, a gentle cry for peace in a world realized through metaphor. “Margaritkele” (“Little Margaret”), in contrast, is a Ländler (the canonic Austrian folk dance in triple meter); in Ullmann’s setting, however, it evokes the innocence of children rather than a traditional Central European courting dance. Ullmann reserves the heightened emotions of the courting dance for the final song, “Ich bin a Maydl in di Yorn” (“I’m Already a Young Woman”). Here we experience a march-like style, seemingly shifting the gendered focus of the Three Yiddish Songs for the first time to the male. Ullmann’s choice to order the songs as a cycle that begins with birth, moves through youth, and then concludes with possibility of marriage, results from his own decisions about the Yiddish songs in Kipnis’s Folkslider. He has retreated from the irony and pessimism of his major works from Terezín, including the opera, Der Kaiser von Atlantis (The Emperor of Atlantis) (1943), in search of a new realization of the unreality of exile, in a past that was retrievable only through song.

Fig. 4 – “Berjoskele” / “The Little Birch” (Kipnis n.d.: 63)

Was it irony or destiny that cabaret prospered after the Holocaust? Does the return to German-speaking Europe of cabaret composers and performers such as Armin Berg, Hermann Leopoldi, Friedrich Holländer, and Hanns Eisler reflect continuity, even the urge to heal? Or does it draw attention, once again, to the disabled condition of European society, unable to provide the cradle for the sickened soul of Jewish exile? In their banality such questions suggest easy answers, and they underestimate the deeper commitment of cabaret performers to the social ills that they gather up as found objects to subject to harsh criticism. Cabaret does not heal; it exposes social illness as a condition that refuses to go away (for the exile cabarets that sprang up in New York City see Klösch and Thumser 2002; on the return of musicians to Europe from exile in the Holocaust see the essays in Köster and Schmidt 2005).

The first response of many listeners to the sixth set of songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile is that they slip into the past, resting on the laurels of a tradition that best conveys nostalgia for what will be no more. Each of the three songs, in its different ways, stands for a repertory of beloved songs. They found their way into the repertory of the New Budapest Orpheum Society after persistent requests following the ensemble’s live performances. “Couldn’t we have a Leopoldi song?” “I remember Spoliansky so vividly from my youth?” “Georg Kreisler is a sort of undying, modern master of the cabaret song!” In the tradition of listening to those who listen to us, we began exploring the return to Europe and the reprise of Jewish cabaret in the recent past.

The set begins with perhaps the best-known song by Georg Kreisler (b. 1922), whose appearances even today attest to the vitality of cabaret. On its surface, “Poisoning Pigeons” could not be more Viennese: Kreisler uses Viennese dialect in the text; the lilting waltz would be fitting for a Viennese inn, or Heuriger; the social critique savagely targets Vienna. There is, nonetheless, a more expansive aesthetic range in the song, evident in a type of memorywork dedicated to Jewish cabaret itself. Even after his return to Europe in 1955 and his move to Basel, Switzerland in 1992, and even upon the revival of his shows in the 1980s, Kreisler has retained the American citizenship he obtained in Hollywood and New York exile (see Kreisler 2001).

Nostalgia works differently for Hermann Leopoldi, and reprises a very different Vienna. Before, during, and after exile, Leopoldi hewed to the tradition of the Wienerlied, literally the “Viennese song,” which localized the nostalgia for simpler times and places, the local neighborhood and the tavern with its gathering of friends (see Fig. 5). It is because of the much sharper satire of Leopoldi’s signature song, “I Am an Irreconcilable Optimist,” that we include it on this CD. A song overwhelming with stereotype, it takes the misery of the everyday and the old ways as its subject matter. The hapless narrator is reminiscent of the broadside characters of an earlier Viennese tradition (see, e.g., the opening tracks of Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano), but here there is a different sort of suffering that is addressed with the irony of possible suicide in the chorus.

The nostalgia of “Tonight or Never” is, in contrast, unmitigated. With lyrics by Marcellus Schiffer, who also collaborated with Paul Hindemith among others, Mischa Spoliansky turns to a truly cloying nostalgia. This is the sound of the Berlin Wintergarten and of the clubs that Tucholsky and Kästner frequented. We hear the sound of that world, but not the substance. Like many songs on Jewish Cabaret in Exile, “Tonight or Never” plays with the irony of time and timelessness, juxtaposing it with the everydayness of the “tonight” of the title. The allegiance to Berlin cabaret, however, is undeniable, for in the end it is the return of “never” in the return of the refrain with which the song rings out.

Fig. 5 – Wienerlied – Ralph Benatsky: “Liebe im Schnee”

With the closing set of two songs by the great jazz musician and film composer, Friedrich Holländer we encounter the bittersweet mixture of nostalgia and tragedy that accompanied the reprise and revival of cabaret in post-Holocaust, post-exile Europe. Ultimately, cabaret is stage music, and it is therefore hardly surprising that the changing media of the stage, especially film, expanded the stage for cabaret from the outset. In the history of film, for example, the first English-language sound film, Alan Crosland’s The Jazz Singer (1927), uses the cabaret stage in its multiple American forms of vaudeville and the revue, as well as jazz dance, with Al Jolson’s characterization of Jakie Rabinowitz/Jack Robin moving between Jewish and non-Jewish musical practices in search of his own identity in exile. The presence of cabaret in early film was no less true in Germany, where the first talkie also took cabaret as its theme. In fact, the very Blue Angel in the title of Josef von Sternberg’s Der blaue Engel (1930) was the name of the wharfside cabaret where much of the film was shot.

The Blue Angel cabaret in the film is significant not only because of its role in establishing Marlene Dietrich’s stardom, but because Friedrich Holländer (1896–1976) created the music performed in the cabaret. By the time he was leading the stage band, the “Weintraub’s Syncopators” in the movie, Friedrich Holländer had already secured a compositional voice that lent itself to film. In the course of the 1920s and 1930s, he forged a style that was musically cosmopolitan and socially critical, not least because of the lyrics upon which he drew, including those by Kurt Tucholsky. Holländer fled in exile to Hollywood in the 1930s, where he wrote the music for films such as A Foreign Affair (1948) and Sabrina (1954) by the exile director, Billy Wilder (1906–2002). For Holländer, exile resolved itself through imagination and through the creation of alternative worlds that cabaret so marvelously makes possible. Following his exile, he entered years of reprise, returning to Germany, where he spent his remaining years creating for the cabaret stage.

A song from Holländer’s own show, Klabund, “Marianka” is one of the finest examples of cabaret song that relied on the popular dance craze that swept European stages between the world wars. The tango provides the signature tune for the character of Marianka, who presents her many personalities and identities in Holländer’s own lyrics, most in the forms of stereotypes, such as a Rom lover, occupying the popular stage of the day. The wild acceleration of “Marianka” gives way to an enigmatic timelessness in the final song on the CD: Friedrich Holländer’s “If the , If the Moon . . .”, with its lyrics by Theobald Tiger, one of Kurt Tucholsky’s most frequently used noms de plume (see Lenze 2007). Throughout his cabaret texts, Tucholsky turns to the night as the ultimate exile from the everyday that increasingly closed in upon interwar Europe. In “If the Moon,” Holländer employs musical references to time itself, the toll of the church bells yielding to the laughing of the heavens at night, merrily tolerating the human frailties that would be suppressed by day. The paths of exile led Holländer and Tucholsky in different directions, one to Hollywood, the other to suicide in Sweden, but together they create a song that charts the paths of exile trenchantly and tragically.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:58

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover: Boris Borvine Frenkel (1895‚ – 1984): Jewish Musicians in the Snow, c.1930 (oil on canvas) © Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded: April 2-4, 2008 in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, WFMT, Chicago

© 2009 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 110