Store

Store

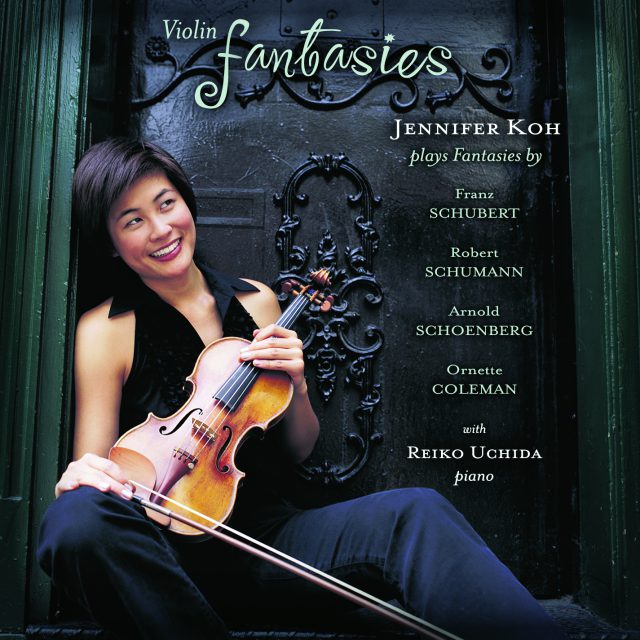

Jennifer Koh: Violin Fantasies

“Fantasy” offers a composer one of the freest possible musical forms. When I first began thinking about this recording, I saw an opportunity to present a program of four very different composers speaking through this very free form in their distinct voices. In the months preceding the recording sessions, I lost two friends in close succession. Fortunately, I had the work of preparing these fantasies to delve into. In the midst of my preparations, I began to perceive a common thread among the pieces, besides the theme of “fantasy.” I began to understand each piece as a life’s journey. Each fantasy expressed itself as an entire life to me: a search to find one’s own path with all of its joys and struggles along the way. I would like to dedicate this recording to my two friends and to the celebration of life.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874-1951)

ORNETTE COLEMAN (b. 1930)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletViolin Fantasies

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The term “fantasia” emerged in music some 500 years ago to describe a work that celebrated the power and ingenuity of a composer’s imagination. Fantasias in the Renaissance and Baroque eras — the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries — were always purely instrumental pieces. Not tied to the requirements imposed by setting words, the composer (or, often, composerperformer) was free to let his fancy roam. In his 1597 handbook, A Plain And Easy Introduction To Practical Music, Thomas Morley (1557–1602) described fantasies as “the chiefest kind of music which is made without a ditty, when a musician taketh a point [theme] at his pleasure, and wresteth and turneth it as he list [likes], making either much or little of it as shall seem best in his own conceit. In this may more art be shown than in any other music, because the composer is tied to nothing but that he may add, diminish, and alter at his pleasure. . . . Other things you may use at your pleasure, as bindings with discords [dissonances], quick motions, slow motions [speeding up or slowing down the rhythmic patterns], proportions, and what you list.”

The 17th-century English composer, theorist, and viol player Christopher Simpson published his thoughts in The Principles Of Practical Music. Morley’s era had thought of fantasias as solos for keyboard instruments or lute. Simpson and his contemporaries saw them as ensemble pieces for viol consort (a Jacobean Restoration version of our string quartet, quintet, or sextet). According to Simpson, “In this sort of music the composer, being not limited to words, doth employ all his art and invention solely about the bringing in and carrying on of fugues. When he has tried all the several ways which he thinks fit to be used therein, he takes some other point, and does the like with it: or else, for variety, introduces some chromatic notes . . . or falls into some lighter humor . . . that his own fancy shall lead him to: but still concluding with something which hath art and excellency in it.”

Simpson’s use of the word “fugue” here is a reference to the freely imitative contrapuntal lines of viol fantasias, not to the rather strict procedures of the choral and organ fugues developed later by Bach and Handel. While the fugue was a principal form of the High Baroque — Jennifer Koh: Violin Fantasies Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux roughly 1700 to 1750 — sonata form became the standard framework of the Classical era. Sonata form, as it evolved in the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, had rather strict procedures too: the exposition, development, and recapitulation of two contrasted themes in a tonic-dominant key relationship. If the opening theme is in C Major, the second should be in G Major; then through development, relying greatly on the manipulation of other key relationships, the themes are brought back together and re-stated, each of them this time in the tonic key. (Despite its name, the dominant never wins out.) Worthwhile pieces in sonata form rarely follow this pattern slavishly — it’s a procedure, not a blueprint — but it is the norm from which ingenious composers devised infinite variants and exceptions. The attraction of sonata form lay in its possibilities for creating contrast, tension, and eventual resolution, achieving a truly “classical” balance and serenity after conflict. Fantasias, being more free-ranging and playful, appeared less frequently than sonatas in the Classical era. Figuratively speaking, Mozart’s several keyboard fantasias are instances of the composer saying upfront that he’s not going to play by the “rules.” Beethoven broke with the fantasia tradition when he included voices along with piano and orchestra in his Choral Fantasy. Earlier, one of his most famous works, the “Moonlight” Sonata, had announced its departure from regular sonata character through its full title: Sonata quasi una Fantasia (Sonata in the Style of a Fantasy). All music has structure; fantasias are no exception. They have a tendency, however, to create their own structures — no doubt a significant part of their appeal for Romantic-era composers whose yearning to unleash the expressive beauty of melody and sonority often came into conflict with the requirements of the sonata form they’d inherited from the preceding generation. Fantasias abound in the musical literature of the 19th century. Particularly popular were fantasies based on themes from operas. Franz Liszt created a number of virtuoso piano suites based on varied operatic tunes titled “Fantasy on themes from . . . ” (fill in the blank). In his colorful “Scottish Fantasy” for violin and orchestra, Max Bruch proceeded in the same way using folksongs. “For the Romantics,” writes critic and historian William Drabkin, “the fantasia went beyond the idea of a keyboard piece arising essentially from improvised or improvisatory material though still having a definite formal design. To them the fantasia . . . provided the means for 6 7 an expansion of forms, both thematically and emotionally. The sonata itself had crystallized into a more or less rigid formal scheme, and the fantasia offered far greater freedom in the use of thematic material and virtuoso writing. As a result, the 19th-century fantasia grew in size and scope to become as musically substantial as large-scale, multi-movement works.” Drabkin cites Schubert’s four fantasias — the “Wanderer” and “Graz” for solo piano, the F Minor for piano duet, and the C Major for violin and piano — as “the first to integrate fully the three- or four-movement form of a sonata into a single movement. The Fantasia for violin and piano is of particular importance because it anticipates the cyclical and single-movement aspects of much of the music of Schumann and Liszt.” Schubert scholar Maurice J. E. Brown has written: “The remarkable accomplishments of the year 1828 give to Schubert’s death [in November of that year] an overwhelmingly tragic aspect,” and later in the same essay, he quotes the inscription on the composer’s tombstone: “The art of music here entombed a rich possession, but even fairer hopes.” Among the creations of Schubert’s last year are three large-scale piano sonatas (Deutsch catalogue numbers 958-960), the String Quintet, the B-Flat Piano Trio, and “The Shepherd on the Rock.” He also completed the song-cycle Die Winterreise and the “Great” C Major Symphony, both begun in the mid-1820s. These last few years of Schubert’s life were full of encouraging signs that his music was about to reach a much wider audience. Publishers were showing more interest, and several public performances took place, including the evening-length allSchubert concert of March 26, 1828, sponsored by the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, the only such event during his lifetime. (Eight months later he was dead, aged not quite 32.) The Fantasia in C, D. 934 (Op. Posth. 159) also received a public performance in 1828, featuring the artist for whom Schubert wrote it the previous year: the Bohemian virtuoso Josef Slavik, a member of the Vienna court orchestra. As Professor Drabkin points out, this is an integrated single-movement work with cyclical aspects: themes recur, restated or transformed, throughout the piece to provide linkage and unity. There are six clearly defined sections, the major one being the third, marked Andantino: a set of variations on an earlier Schubert song, Sei mir gegrüsst, “I Greet Thee” (D. 741, poem by Friedrich Rückert, set ca. 1822). Schubert’s preoccupations in the Fantasie are not primarily experimenting with structure, developing cyclical procedure, or expanding the general concept of the fantasia. As is usually the case with Schubert, the main impression the piece imparts is one of overflowing lyricism. Melodies pour from both players as they interweave their lines and comment on each other’s progressions as equal partners. The theme set out in the Andantino (a blend of the vocal and piano melodies from the song) at first evokes the emotions of love and longing expressed in Rückert’s poetry, but we are soon engaged by the fantasia’s other major preoccupation: virtuosity. In all six sections, the melodic element is combined and contrasted with demanding figurations for both players: rapid scale patterns, percussive piano octave sequences, trills, tremolos, chords (on both instruments), runs in 16th and 32nd notes, mini-cadenzas, all ranging into the violinist’s highest and lowest registers and all the way up and down the keyboard. Schubert’s typically rich harmonies are made even more complex by chromatic notes and passing semi-dissonances, with frequent modulations and shifts between major and minor modes. The sections may be summarized as follows: Andante molto, mainly C Major; Allegretto, A Minor/A Major/E-Flat Major; Andantino, song variations, A-Flat Major; a brief Tempo I interlude, C Major again; Allegro vivaceAllegretto, proceeding C Major/A Major/A Minor/A-Flat Major and incorporating further variations on the song theme; and a final Presto, back in C — a tumultuous conclusion with the violin’s high-register exultation supported by equally exuberant octave passages from the piano. Robert Schumann wrote his Fantasie, Op. 131 for violinist Joseph Joachim (1831–1907), a composer in his own right and also a significant collaborator with other composers, especially his close friend Johannes Brahms. Brahms’s Op. 77, one of the greatest of all violin concertos, owes at least some of its shape and substance to the advice offered by Joachim, the dedicatee. The virtuoso was also the dedicatee of the Violin Concerto in G Minor by Bruch, who also accepted Joachim’s technical advice, and of the A Minor concerto by Antonín Dvorˇák. The Lower Rhine Music Festival held in Düsseldorf, Germany, in May 1853 found the youthful Joachim performing Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, a work that had been slow to enter the standard concert repertory. Perhaps it took an artist of Joachim’s combined skill and musicianship to plumb its depths. In any 8 9 event, Joachim championed the piece on concert tours all his life. He viewed it the way great violinists do today, as an unrivaled masterwork. In Joachim’s audience at the festival was Robert Schumann: middle-aged, physically unrobust, psychologically unstable, yet still one of the leading composers of the day, and one capable of appreciating both Beethoven’s music and what Joachim did with it. Schumann remembered the occasion that summer, when he received a letter from Joachim that asked him to “follow Beethoven’s example and provide us poor violinists, who have so few opportunities besides chamber music, with an opus out of the deep shaft of your creative genius.” So it came about that two of Schumann’s last works were the Concerto in D Minor for violin and orchestra, and the Fantasie in C Major for those same forces. Joachim (typically) made some revisions to the solo part, with Schumann’s blessing. He gave the work’s premiere in October 1853 with Schumann conducting, and continued to play the piece throughout his career. Since his day, it has not received quite the same attention. We hear it on this CD in Schumann’s version for violin and piano. Schumann acknowledged that the orchestra was “not overly active” in the Fantasie, which is clearly propelled by its virtuosic solo writing. Arranged for keyboard, the orchestral part becomes a sequence of rich, closely harmonized chords and octave doublings. In Schubert’s fantasia, violin and piano play together almost continuously; in Schumann’s they frequently alternate, the pianist playing the orchestral “tutti” passages alone, then retreating into light accompaniment as the soloist re-enters. The piece is very much a concerto in miniature. The name Fantasie is still apt, however, since the three main themes laid out in the slow A Minor introduction are freely developed and recombined in imaginative ways throughout the main section, marked lebhaft (the German equivalent of allegro, or “lively”). The piece’s emphasis on virtuosity puts it within both the concerto and fantasia traditions. The violinist’s music is in nearly constant motion, with fleet figurations that challenge both fingers and bowing arm, while dazzling listeners’ ears, especially in the pyrotechnical solo cadenza. Schumann was an intensely lyrical composer, but gentle melodiousness was not his goal here. Instead, he sought and achieved a stunning display of string brilliance. While numerous Romantic composers experimented with fantasias, cyclical form, and other single-movement genres such as symphonic poems, the principles of sonata form continued to characterize a great deal of concert and chamber music. The tension and resolution inherent in the contrasting of tonic and dominant keys still formed an important foundation for extended compositions. The tradition of tonic-dominant, key-based, harmonically organized music gained the name of tonality — and like everything else in the ever-changing art of music, no sooner did it become a received convention than it started to change and break down. Richard Wagner, a thoroughly tonal composer, nevertheless stretched the convention to such an extent, via chromaticism and extremely complex harmonies, that the prelude to Act One of his music-drama Tristan und Isolde has no recognizable tonal center. It is not in any key. Some musicologists point to this prelude (from the 1860s!) as the beginning of modern music. Wagner’s lateRomantic successors, who also expanded and blurred standard tonality, included Mahler, Richard Strauss, Bruckner, and the young Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951). Schoenberg, one of the 20th century’s most original geniuses, combined compelling intellect with strong spirituality and profound emotional depths. In the early 1900s he came to the conviction that music needed a new language and a new structural method that would dispense with tonality altogether. His experiments with totally free music (pure atonality) essentially led nowhere. He eventually devised a different kind of pitch organization that he called serialism. In tonic-dominant tonality, notes are assigned values: the note of the tonic key — say, middle C on the piano for C Major — and the chords built upon it are of more importance than the other notes of the scale. Everything is organized to establish that tonic. In serialism, each of the 12 notes of the chromatic scale (white and black keys on the piano from middle C up to B-natural) has an equal value. Chords based on consonant intervals like major and minor thirds become nonexistent, or at most coincidental. An entire piece or single movement is based on a row, an arrangement in any order of the 12 notes of the scale. This row can be presented straightforwardly, or in reverse (retrograde), or inverted, with the original intervals of the row turned upside down: instead of going up from middle C to (say) E-flat, go down a minor third from C to A. All these presentations of the row can be combined, broken up, recombined, etc., to create a kind of continuous development. What makes this kind of music difficult and challenging is that all this development is being worked on a “theme” that is not as memorable, or even discernable, as anything that could be called a “tune.” Schoenberg declared that the row and its variants did not need to be heard in 11 order for the music to be comprehensible. In fact, the row ideally should not be discernable: the row and its manipulations were tools for the composer, not aids for the listener. The extreme dissonance of clashing pitches and contrapuntal lines in serial music require listeners to approach it in a different way. Melody is obviously not the focus. Elements left to be enjoyed are rhythmic propulsiveness, dramatic climaxes, dynamic contrasts of loud and soft, virtuosity, and contrast between different tone colors — all of which may be found in Schoenberg’s Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment. Written in 1949 and dedicated to the memory of violinist Adolph Koldofsky, it was his last instrumental work. The title is very exact: the violin part was written first, the piano part added later. The two are usually complementary, sometimes confrontational, tossing motives back and forth in a manner that often seems random, but is in the end curiously satisfying. Laid out in four linked sections, the last a condensed and varied version of the first, the piece is firmly in the fantasia tradition of virtuosity and emotional exuberance. It could be called a rhapsody: the violin shouts and exults, playing frequently in double stops (two notes played simultaneously on different strings) and jumping through dissonant, exotic intervals of sevenths, ninths, and augmented fourths. The pianist responds, or contradicts, with rumbling runs, pounding chords, and occasional evanescent three- or four-note motives that fly back and forth between the keyboard’s treble and bass registers. The violin is all over the place too: high-high notes are followed by mellow tones on the low G string, then soar back up again. Pianist Glenn Gould offered this impression of Schoenberg’s Phantasy in notes for a recording: “The Fantasy started life as a fiddler’s dream, a long, rhapsodic statement for solo violin, and, almost as an afterthought, Schoenberg attached an accompaniment that was barred from any competitive function. The piano introduces no theme and recapitulates none. Melodically and rhythmically subservient to the violin, it interjects its understandably cranky comments at . . . offbeat moments [that] will least impede the fiddle’s self-indulgent monologue. There is, indeed, something incipiently aleatoric about this work. Although a recapitulative relationship exists between the outermost of its episodes, one feels that the intervening segments might be juggled ad libitum without compromising any structural objectivity.” Such juggling might or might not work; there’s a certain inevitabil10 ity about the way the piece unfolds, improvisatory as it sounds. Perhaps it’s the union of these two attitudes that gives us a feeling of satisfaction even in the midst of powerful dissonance. “Coleman,” says composer-teacher-conductor Gunther Schuller, “has opened up unprecedented musical vistas for jazz, the wider implications of which have not yet been fully explored — least of all by his many lesser imitators.” A saxophonist, composer, and sometime violinist born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1930, Ornette Coleman was influenced by Charlie Parker, by the rhythm-and-blues tradition, and by folk music. Largely self-taught, he spent a number of years in and out of various bands and in and out of favor with other jazz artists. In 1975 he founded an electric band called Prime Time, whose music blended styles ranging from jazz improvisation to rock to the traditional music of Morocco. In the 1980s he performed with Pat Metheny. “Trinity” was unveiled as part of an “Ornette Coleman Celebration” at Carnegie Hall in 1987. In three sections, the last subtitled “Swing,” “Trinity” harks back to the 16th-century Spanish lutenists and Elizabethan keyboard artists who first gave us fantasias by creating original tunes and exploiting all their possibilities. Coleman’s solo-violin piece sounds like one long improvisation, drawing on his jazz experience without sounding particularly jazzy. It’s almost perpetual motion: short motives follow each other in quick succession, sometimes using chromatic intervals, sometimes broken-up triads, sometimes a sequence totally unexpected. The music wanders, explores, turns in upon itself, slows down, speeds up. It’s improvisation re-thought, then carefully notated and organized: the essence of what a fantasia was and is and should be.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time: 55:36

Recorded: February 25-27 and March 19-20, 2003 at the Academy of Arts and Letters, NYC

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer: Jeanne Velonis

Digital Editing: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond & Pete Goldlust

Front Cover Photo: Janette Beckmann

Notes: Andrea Lamoreaux

PUBLISHERS: Schoenberg: © 1952 CF Peters; Coleman: © 1987 Ornette Coleman

© 2004 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 073