Store

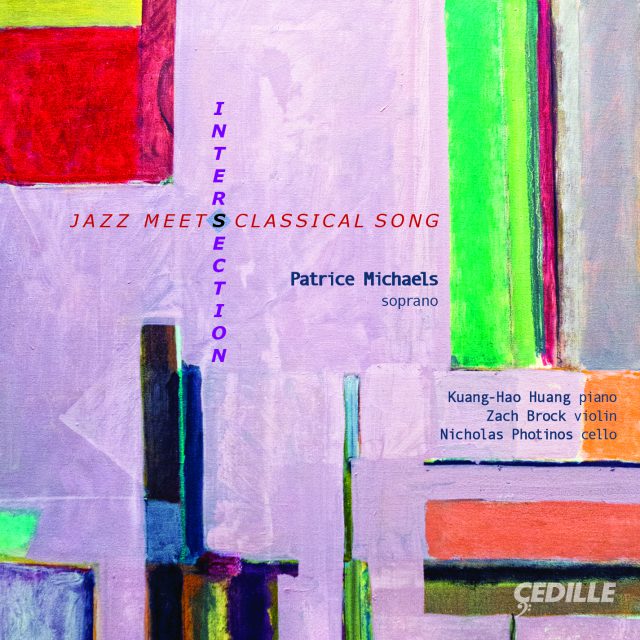

Acclaimed lyric soprano Patrice Michaels, “a formidable interpretative talent” (The New Yorker), conceived and headlines this inventive, wide-ranging two-disc project of 26 songs where classical music and jazz find common ground in ways that will delight fans of both musical genres.

The program ranges from jazz-influenced classical works of the 1930s by Hungary’s Tibor Harsanyi and France’s Francis Poulenc to contemporary pieces by Randall Bauer and Laurie Altman, whose music shows his love of both Igor Stravinsky and jazz pianist Art Tatum. Contrasting pieces by Lee Hoiby and John Musto — masters of post-Romantic American song — share billing with jazz classics by Swing Era legends George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, and Billy Strayhorn. From composer Chuck Israels, come gorgeous piano and voice settings of American folk songs. INTERSECTION closes on a Latin American note, with contributions from Argentinean composer Andres Beeuwsaert and Brazil’s Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Preview Excerpts

TIBOR HARSANYI

FRANCIS POULENC

LAURIE ALTMAN

Two Re-Imaginings

NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN

GEORGE GERSHWIN

DUKE ELLINGTON

BILLY STRAYHORN arr. LABELLA

Suite Strayhorn

KAPUSTIN

LEE HOIBY

JOHN MUSTO

PATRICE MICHAELS

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletIntersection: Jazz Meets Classical Song

Notes by Neil Tesser

“Jazz was my first musical passion,” writes Patrice Michaels, “and has remained hugely influential and inspiring for me — a sort of ‘silent partner’ behind my work as a classical singer.” On INTERSECTION, she offers a more overt embodiment of that inspiration, in an eclectic but cohesive program that blurs the line between her two musical loves.

Such fusions, while not unheard of, don’t occur that often; still less often do they succeed. At first glance, this doesn’t compute, since jazz and classical music have so much in common. Of all the sonic genres and idioms, these two demand of their adherents the most knowledge and training: only jazz players rival the classical world in terms of performance technique, music theory, range of style, complexity of interaction. The rift develops when a number of other items come to the fore, most notably improvisation, rhythmic flexibility, and interpretation — at which point the complaints pour in from both sides of the divide. Generally speaking, the classical world grows suspicious when a saxophonist bends notes away from their perfect pitch, or a pianist executes a run with more expressiveness than precision. From the perspective of jazz folks, the problem usually boils down to the deceptively simple dismissal, “It doesn’t swing,” referencing the essential but elusive (and perhaps undefinable) quality of infectious propulsion that grew from the earliest syncopations into the complicated polyrhythmic dance at the heart of good jazz — whether it comes wrapped up in a 20-piece big band or a piano-bass duo. Without swing, the most brilliant jazz improvisation would sputter and collapse; with it, the simplest variation can move the soul.

I would argue that much classical music actually does “swing,” in a manner that predates jazz — as anyone who’s felt the urge to finger-snap along with a Bach fugue can attest — but that’s fodder for another discussion. The basic dichotomy still holds true: for most of the world, jazz swings, and classical music does not.

But on INTERSECTION, Patrice Michaels swings.

Even within the confines of the written page, a condition that characterizes all the pieces on this album, she finds that hidden lilt, whether within an angular phrase or a single note. (And at various points, she moves beyond the written page, gently but effectively improvising on pieces by Poulenc, Gershwin, and Bauer.) Those who have heard her perform in person or on disc know that she boasts superb pitch, an impressive vocal range, and a strong instrument as versatile as it is lovely. It’s her ability to inhabit this music’s rhythmic essence that provides the bonus here, allowing her to connect the classical and jazz aesthetics with refinement as well as soul. This ability informs her reading of the album’s carefully chosen mix of material, drawn from European salons and Tin Pan Alley, conceived in studios behind the Iron Curtain as well as in the sunlit cafes of Brazil, and encompassing original source material and vibrant reconceptualizations. It allows Michaels to turn a unique (and uniquely challenging) program into a garden of earthy delights.

Before emerging as an acclaimed lyric soprano (whose musical intellect matches her vocal gifts), Michaels studied as a composer; this album includes a work commissioned from her in 2013, her first composition in many years. During her hiatus from composing, Michaels developed a distinctive skill for writing lyrics, represented here by her words to a jazz classic by Billy Strayhorn and by four poems that engage a new suite by Randall Bauer. Before she sang or wrote, however, Michaels entered college as a flutist; here she nods to her background in instrumental praxis by accompanying herself at the piano on two pieces. And her training in theater — which informs her interpretations of whatever she sings — comes center stage in her reading of a 15th-century French poem, which she interpolates into Duke Ellington’s “Paris Blues.” While this album’s title ostensibly alludes to a crossroads of jazz and classical music, it equally describes the intersection of Patrice Michaels’s various talents.

Michaels has organized INTERSECTION with a keen attention to detail and balance. She has positioned the song cycles — performed with her full ensemble of violin, cello, and piano — opposite individual pieces that feature only piano and voice. She has further grouped those individual songs into miniature sets of their own. An example of such grouping occurs within the first four tracks of Disc One, which serve as building blocks for the entire program. The works by Tibor Harsányi and Francis Poulenc “define the origins of the intersection,” Michaels explains, and each receives “personalized treatment and arrangement by the performers, well beyond the indications of the score.” This concept is exemplified by Harsányi’s “Vocalise Etude,” from 1930. The vocalist’s score shows only the melody line; the composer didn’t even include suggested syllables. Michaels made the decision to add sound effects imitating a trumpet’s wah-wah and cup mutes, along with guttural growls, to elicit “the entertaining influences the Hungarian Harsányi must have drawn from when he wrote this little piece in Paris” (a hotbed of early jazz).

In a similar vein, Poulenc’s “Violon,” from the eminent French composer’s 1939 suite Fiançailles pour rire, includes a sparkling solo by Zach Brock, “the pre-eminent improvising violinist of his generation,” in the opinion of this writer. The performance also incorporates Michaels’s own wordless variations on the melody the second time through, where she improvises in tandem with Brock. The next two pieces, by contemporary composer Laurie Altman, indicate how these earlier jazz-influenced classical pieces have evolved into a true hybrid. Altman’s music, while firmly rooted in the classical world, “could not be written without a deep knowledge and practice of jazz,” says Michaels, adding that “one can clearly hear both his love of Stravinsky and his reverence for Art Tatum” (the blind jazz pianist whose blazingly virtuosic performances struck a chord with both classical and jazz audiences in the 1930s and 40s). Michaels calls Altman’s approach to these pieces, and also Gig Songs on Disc Two, “the ‘native tongue’ of this project.”

The grouping of pieces by Ellington, the Gershwins, and Strayhorn suggests the “origins of the intersection” from the jazz perspective. The latter two composers had rigorous classical training, while Ellington’s classical inter-ests grew over time (especially during his association with Strayhorn). This performance of George Gershwin’s “Liza,” with his brother Ira’s lyrics, features some light improvisation by both piano and voice; more telling is the use of operatic technique on what became a jazz standard shortly after it debuted in 1929 (in the musical Show Girl). While we’re now used to hearing it sung with relaxed phrasing in a jazz context, this reading hews closer to how audiences of the time would have heard the song, reminding us that when it appeared, the American musical had not completely cut its ties to European operetta and the English music hall. Meanwhile, in his arrangement of the Strayhorn songs, Pete Labella expertly incorporates the majesty of the recital stage and the mystery of the Far East (a prominent influence in the Ellington-Strayhorn ouevre) into his voicings.

The next grouping brings a heightened literacy to the mix. Lee Hoiby’s distinguished career as one of America’s leading art song composers abounded in the romantic lyricism heard in “Insomnia,” one of three songs in the 1990 cycle Three Ages of Women (based on poems by Elizabeth Bishop, who served as U.S. Poet Laureate in 1949–50). The delightfully cheeky “Penelope’s Lament” comes from Penelope, a seven-song cycle by celebrated American composer John Musto and poet Denise Lanctot. Premiered in 2000, the cycle offers a modern-day take on the long-suffering character from The Odyssey. “Penelope’s Lament” is followed by Michaels’s own work, “Anita’s Story,” commissioned for the 80th birthday of her mother-in-law. The text, supplied by a secretary to the dedicatee’s husband, recounts Anita’s meeting with the missus, and achieves unexpected significance when you learn that Michaels’s mother-in-law is Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second woman appointed to the United States Supreme Court.

Michaels’s lyrics for Neighborhood Songs, by Macalester College-based Randall Bauer, have a personal bent of their own. “These poems came out of necessity,” she explains. “Randy had agreed to write a suite for INTERSECTION, but we weren’t coming up with words that grabbed us.” So Michaels took it upon herself to supply the texts. Observing the classic literary advice to “just write what you know” (and also noting the title of the suite), she stuck to topics close to home and heart: a vocalizing local security guard; the cacophony of neighborhood canines; the punctilious dedication to craft of “the local record producer” (Michaels’s husband toiling away in the basement); and the sounds emanating from the nearest El(evated train) stop. The songs benefit from Michaels’s gorgeous intonation and playful phrasing, and her performances understandably display a knowing intimacy.

Two exquisite songs by Nils Lindberg reflect the arc of the Swedish composer’s career, writing for jazz band as well as symphony orchestra and choir. Perhaps more important for our purposes, he spent many years arranging, conducting, and accompanying (at the piano) the late Swedish soprano Alice Babs, who brought an ethereal power to her own collaborations with Duke Ellington in the 1960s. Lindberg’s melodies would flatter any singer, and these cover an intriguing gamut: the first channels one of Shakespeare’s best-known sonnets, while the other uses poetry by revered American jazz bassist Red Mitchell, who spent the last 25 years of his life in Stockholm and wrote a fair amount of poetry and lyrics. Michaels accompanies herself on the first of these; the second takes advantage of cellist Nick Photinos’s previous life as a jazz bassist to add a brisk “walking” line when the piece goes up-tempo on the repeat. Next come three examples of classic Americana: the Appalachian song “He’s Gone Away,” which pre-dates the Civil War, the early 20th-century ballad “Frankie and Johnny,” and the 19th-century African-American spiritual “Balm in Gilead.” All three were arranged by Chuck Israels—another jazz bassist, whose work with pianist Bill Evans honed his gift for romantic melodicism —as art songs for his wife, the classical singer and esteemed voice teacher Margot Hanson. (“Gilead” in particular showcases Michaels’s gift for improvised melodic paraphrase.)

At strategic points throughout the program, Michaels has placed four piano pieces written by Nikolai Kapustin, the rangy Ukrainian-born composer who first established his reputation in jazz as a pianist, composer, and arranger during his teenage years in Moscow. These early seeds of Kapustin’s art blossomed into the swingy rhythms and exuberant melodies of these piano solos, which Kuang-Hao Huang captures with admirable gusto and loose-limbed fidelity. These pieces have the self-surprised quality of improvisation (and indeed may have begun as such, although they are performed here exactly as written). Michaels sees these selections as the “sorbet between courses” of this double-disc musical feast. If Laurie Altman’s compositions constitute the voice of this project, Kapustin’s seamless blend of jazz and classical techniques exemplifies its soul.

The album concludes with a nod to the Latin American strain that has infused jazz from its New Orleans origins. Michaels transcribed “Sonora,” by Andrés Beeuwsaert, from the Argentinian composer’s own recording (with Brazilian singer Tatiana Parra). Following it is a typically voluptuous song by Antônio Carlos Jobim and his great collaborator, the Brazilian poet Vinícius de Moraes (the two men primarily responsible for the bossa nova movement of the 1960s), arranged by Seattle-based Brazilian pianist and scholar Jovino Santos Neto. Before these zephyrs from the Southern Hemisphere come Gig Songs, in which Laurie Altman radically reworks a handful of gems from the Great American Songbook. More than any of the other hybrids that fill this album, these re-imaginings are disorienting — we’ve heard these songs before, but not like this — and all the more fascinating as a result. Rigid purists would surely blanche at the liberties Altman takes with these keystone compositions by Rodgers, Berlin, and Wilder. But then, such purists will have abandoned this album long before reaching these tracks — which would be their loss, I hasten to add.

NEIL TESSER is a GRAMMY®-winning Chicago writer, critic, and broadcaster specializing in jazz. He is the author of The PLAYBOY Guide To Jazz (1998) and edited Learning To Listen (2013), the award-winning autobiography of vibraphonist and educator Gary Burton.

Album Details

Total Time: 101 minutes

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, at the University of Chicago

January 8–11, February 18, March 23, 2014

Cover Art: Morris Barazani, City Landscape (2005)

Front Cover: Design Sue Cotrill

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

Photography: Corey B. Lindsay

© 2014 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 149