Store

Store

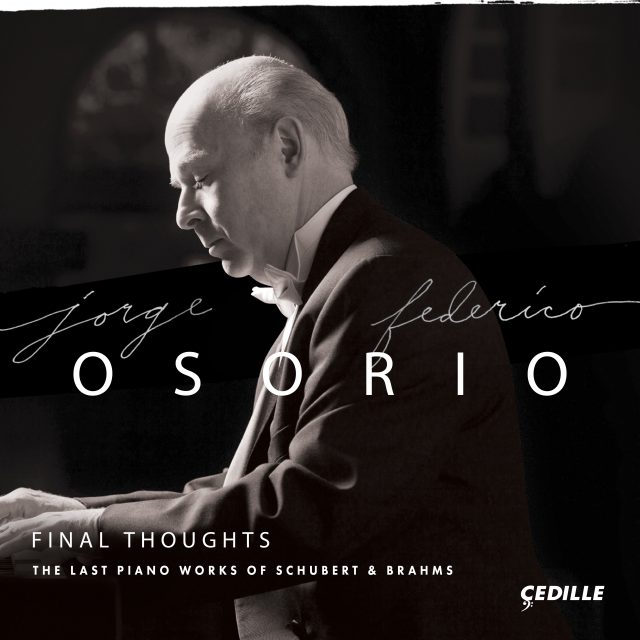

Final Thoughts – The Last Piano Works of Schubert and Brahms

Jorge Federico Osorio, “an imaginative interpreter with a powerful technique (The New York Times), deftly pairs Brahms’s final solo piano works with those by Schubert for an inventive program of richly satisfying works that capture the essence of each composer’s towering individuality.

Osorio records Brahms’s Three Intermezzos, Op. 117, and Six Piano Pieces, Op. 118, for the first time. He revisits Brahms’s Seven Fantasies, Op. 116, and Four Piano Pieces, Op. 119, which he last recorded nearly two decades ago, to great acclaim: “Quite marvelous,” said BBC Music Magazine. “It’s clear that Jorge Federico Osorio is an important Brahmsian,” proclaimed the Chicago Tribune. On his new album, Osorio’s penchant for color accentuates the individual character of these concentrated miniatures.

On this, his first Schubert recording, Osorio, whom the Los Angeles Times called “one of the more elegant and accomplished pianists on the planet,” presents the composer’s final two Piano Sonatas, D. 959 and D. 960, epic in scale and brimming with melodic invention. Osorio’s insights into the music’s architecture yield eloquent performances of these spacious, ambitious masterworks. Osorio’s Cedille Records albums of Mexican and Spanish music have introduced the pianist to new audiences worldwide. Now they can hear his artistry in more of the core German repertoire that has been central to his concert life for decades.

Osorio has performed Brahms’s Piano Quintet with cellist Yo-Yo Ma and musicians from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The Mexican-born, European-trained virtuoso has served as artistic director of Mexico’s Brahms Chamber Music Festival. He has received the Medalla Bellas Artes, the highest honor granted by Mexico’s National Institute of Fine Arts, and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra’s Gina Bachauer Award.

Listen to Steve Robinson’s interview

with Jorge Federio Osorio on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828)

Sonata in A major, D. 959

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Seven Fantasies, Op. 116

Three Intermezzos, Op. 117

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletFinal Thoughts - The Last Piano Works of Schubert and Brahms

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

The death of Franz Schubert, in November 1828 at the age of 31, was premature even by the lifespan standards of the early 19th century. In an instance of sad irony, March of that year saw Schubert finally score a major triumph: a public concert in Vienna of his own music, well performed, well received, and even profitable (the composer had hitherto been chronically short of money). Previous to that event, his music had been known and admired mostly through word-of-mouth fame among his wide circle of friends: poets and fellow musicians who appreciated his talent but were usually unable to help him get wider recognition. Publishers were interested in his songs and short keyboard pieces but didn’t exhibit much enthusiasm for works such as symphonies and string quartets.

But he never gave up, and his final years added up to one amazing burst of creativity. Documenting those years we find the completion of his last symphony, nicknamed the Great C Major; the song-cycle Winterreise and the songs later collected into the set called Schwanengesang (Swan Song), his sixth mass setting, two piano trios, his last string quartet (No. 15) and incomparable String Quintet, and the set of three piano sonatas that he sketched in the summer of 1828 and completed in September. Having numbered the finished copies Sonatas I, II, and III, he seems to have intended them as a cycle. He had written a number of sonatas for piano previously, but here he strikes out on a new path. The sonatas are interconnected in terms of thematic similarities and their similar usage of extremely free modulations and explorations of many different keys, some of them harmonically “remote” from the tonic keys in which the sonatas are actually cast. In this sense, Schubert was looking ahead to the Romantic era of increasing harmonic freedom, while still sticking to Classical sonata form, used in his own way.

The distinguished pianist Alfred Brendel — a premier interpreter of music by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Liszt as well as Schubert — studied the sketches for the sonatas as well as their final forms (not all composers’ first versions survive, but these did). He commented:

Examination of Schubert’s sketches for the sonatas reveals him as highly self-critical; moreover, it shows that the “heavenly lengths” of the sonatas were actually a later addition, not conceived from the start. In his subsequent corrections, Schubert elaborated on his themes and expanded them, giving them more “musical space” … proportions are rectified, details start to tell, fermatas suspend time. Rests clarify the structure, allowing breathing space, holding the breath or listening into silence.

The phrase “heavenly length” is a quote from Schumann, who used it to describe the nearly hour-long Great C Major Symphony. The last three piano sonatas are also notable for their length and somewhat unusual for being in four movements, instead of three. In D. 959 and 960 we have sonata-allegro, slow movement, scherzo with trio, and sonata-rondo.

Commentators have found connections between the themes of the sonatas and some of Schubert’s songs, and they’ve pointed out the sense of “wandering” in the far-ranging modulations through which the sonatas progress. The image of the wanderer is evoked in many Schubert lieder, certainly in Winterreise and in his final vocal scene, The Shepherd on the Rock. But there’s no need to impose extra-musical images on the sonatas: these are works that stand on their own. A striking characteristic is the composer’s use of cyclical form: deriving later themes and harmonic progressions from earlier ones, a technique that’s often credited to the innovations of Liszt, but which was actually pioneered by Schubert.

The Sonata in A Major, D 959, has a first movement marked simply Allegro (Lively). Its opening theme is a series of chords followed by arpeggios, motives that will be echoed later in the piece. The second theme, more songlike, modulates traditionally to the dominant key, E major, but in between Schubert touches on several other keys. The development is based mostly on the second theme; the recapitulation leads to a coda based on the first theme. In the second movement, Andantino (rather slow), the basic key is F-sharp minor, the relative minor of A major; it’s an extended A-B-A form whose “B” section is a kind of fantasia with chromatic accents. The Scherzo picks up the pace with its fast tempo indication, Allegro vivace; the trio section is slower, and once again a number of different keys are explored through ingenious modulation sequences. For the finale, Schubert borrowed a theme from one of his earlier piano sonatas and casts the conclusion as a sonata-rondo: several recurrences of the main theme with episodes and a development section in between. The final, emphatic coda, marked Presto, is a transformation of the theme heard at the very start of the piece.

Rather unusually, the tempo marking for the first movement of the Sonata in B-flat, D 960, is not Allegro but Molto moderato. There are three main thematic presentations, one in the home key with a striking trill, one in the minor mode, and one in the expected dominant key, F major. All of these ideas are further explored in the development. The Andante sostenuto second movement, emphasizing sustained tones at a moderate pace, starts in the key of C-sharp minor which, according to the traditional key structure of Classical sonatas, is very “remote” from the sonata’s home key of B-flat. This is once again in A-B-A form, with a contemplative main theme. This sonata’s Scherzo is also marked Allegro vivace, but with the addition this time of “con delicatezza” — delicately, indicating a light-fingered touch through the rapid modulations, plus a Trio section cast in the minor mode. The finale is tonically ambiguous to start, although it will end firmly in the tonic key of B-flat after a great deal of thematic and harmonic exploration. Its tempo starts out Allegro ma non troppo — not too much — and later moves to Presto. This is an exceedingly dramatic movement with complex rhythms as well as thematic intricacies that harken back to ideas introduced earlier.

The sonatas were published posthumously, and Schumann, although a great admirer of Schubert’s work, seems not to have cared for them very much. Johannes Brahms, on the other hand, regarded them as masterpieces. The careers and life-cycles of Brahms and Schubert could not have been more different. While Schubert labored in relative obscurity, in the European musical world of the late-19th century Brahms was universally acknowledged as the preeminent master, thanks to his symphonies, chamber works, and choral pieces including the great German Requiem. Respected and honored, the mentor of Dvořák and great friend of pianist-composer Clara Schumann and violinist-composer Joseph Joachim, he entered the decade of the 1890s with a curious kind of pullback from his achievements. After completing his second string quintet, he told his publisher he wouldn’t send any more new works, that it was time for “younger folks.” This attitude changed when he encountered the artistry of a virtuosic clarinet player, Richard Mühlfeld, for whom he composed a trio, a quintet, and two sonatas. Brahms’s last years also saw the creation of his Four Serious Songs, a set of chorale-preludes for the organ, and the four sets of piano pieces heard here. The clarinet sonatas, also playable on viola, are happy pieces, but the trio and quintet, and certainly the songs and organ pieces, have tinges of Brahms’s signature “autumnal” melancholy. It was in this musical mood that Brahms turned back to his own instrument, the piano, for a series of short, introspective works of different names (Intermezzo, Capriccio, etc.), that he thought of simply as Klavierstücke: piano pieces. In miniature, they reveal his total mastery of his craft: harmony, counterpoint, melodic variation, rhythmic complexities, the relationships between main themes and accompanying figures. Probably all written between 1891 and 1893, they were published in four separate sets.

Pianist Orli Shaham has commented, “I am constantly amazed at the layers of complexity Brahms achieves through the most simple means.” These are in fact simple pieces, though backed up by the highest compositional skill, and they are very intimate expressions of musical thought. They might best be heard by imagining that you are playing them yourself, instead of listening to someone else, and thus envisioning Brahms playing them for himself alone. To the first set he gave a rather fanciful overall name: Seven Fantasies. Individually they are named Capriccio — three fast-paced, rather dramatic pieces — and Intermezzo — four more lyrical and thoughtful works. All but two of the Intermezzos are cast in minor keys.

What is an Intermezzo? In the realm of instrumental music, it doesn’t have particular meaning; in the world of opera, it means a short passage for the orchestra alone, usually to cover a scene change. It’s an arbitrary title that Brahms used for the set of three pieces he published as Op. 117. The first has an inscription from a Scottish lullaby, and Brahms called this little vignette “a lullaby of my sorrows.” There’s a sense of unsatisfied yearning in each piece; two out of three are in minor keys, emphasizing the sadness.

The six pieces of Op. 118 were published as just Six Piano Pieces, although they have individual titles, again, mostly Intermezzo. The first two make a contrasting pair: one tempestuous in A Minor, the other expansive in A Major. A “Ballade” might suggest storytelling, although if there is a story behind this one in G Minor, it is inscrutable. Another Intermezzo, in F minor, is paired with a lyrical Romance in F major. The finale is an Intermezzo in the unusual key of E-flat minor, that he sent as a special gift to Clara Schumann.

The final set, published as Four Piano Pieces, starts with a bitter Intermezzo in B minor, followed by an Intermezzo in E minor whose second section is a sunny evocation of the Austrian Ländler folk dance. A brief and light-hearted Intermezzo in C follows before the starkly dramatic finale, a Rhapsody, indicating turbulent emotions, that opens in the usually placid key of E-flat major but ends in an emphatic E-flat minor. While there’s no way of knowing what Brahms had in mind when he created this miniature masterpiece, it does impart a feel of final summation.

Andrea Lamoreaux is Music Director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s Classical Experience

Album Details

Total Time:

Disc 1 (77:20)

Disc 2 (79:24)

Producer James Ginsburg

Engineer Bill Maylone

Recorded June 27–30 and July 26, 2016, Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, University of Chicago

Steinway Piano

Piano Technician Ken Orgel

Graphic Design Twin Collective

Cover Photo Todd Rosenberg

© 2017 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 171